Bleb-related ocular infections can occur months to years after the initial surgery. An infected bleb can soon become a dire situation, since the fluid within the bleb is continuous with the anterior chamber, and the infection can rapidly spread posteriorly. In this article, we provide a run down of risk factors for infection and discuss how you can prevent and treat it.

Clinical Findings

A bleb infection can involve the subconjunctival space, the anterior segment and the vitreous cavity. Usually the spread of infection proceeds in that order, with an infected bleb (blebitis) progressing to anterior chamber and then vitreous involvement, also called bleb-related endophthalmitis.

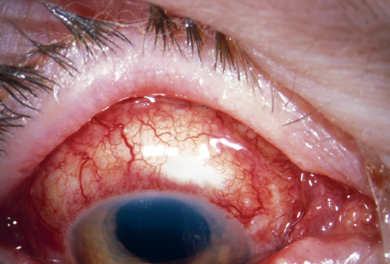

|

| Figure 1. Blebitis with tremendous conjunctival injection three days after intensive topical and oral antibiotics. |

When a patient presents at your office, common subjective complaints include ocular pain, foreign body sensation, blurred vision and tearing. The patient may recall a history of a red eye with a discharge. Examination will reveal conjunctival and ciliary injection, most intense around the bleb edge, and purulent discharge. The bleb typically has a milky-white appearance with loss of clarity, and you may observe a pseudohypopyon within the bleb.1 A positive Seidel's test is common. Some pa-tients may have hypotony, and even a flat anterior chamber. Alternatively, an in-creased intraocular pressure is possible due to internal closure of the sclerostomy site with purulence and debris. If there is an anterior chamber reaction, corneal edema, keratic precipitates and hypopyon may occur. Vitreous cells are diagnostic of posterior segment involvement. If the media are not clear, B-scan ultrasound can help diagnose infection of the posterior segment.

Risk Factors

The incidence of late endophthalmitis after guarded filtration procedures depends on several factors, such as:

• The use of 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin-C during glaucoma surgery probably increases the incidence of late infectious complications.2,3,4 While antifibrotic agents produce thinner blebs that enhance filtration, they also lead to an increased incidence of bleb-related infections. One study reported an incidence of endophthalmitis after trabeculectomy with 5-fluorouracil (mean follow-up of 23.7±16.3 months) of 3 percent in cases performed superiorly.4

A 2.1-percent incidence of bleb-associated endophthalmitis after trabeculectomy supplemented with mitomycin was reported in another study after a mean follow-up of 16 months.5 Other researchers found an incidence of endophthalmitis after mitomycin filtering procedures performed superiorly of 1.1 percent after 18.5 months of follow-up.6 A 2002 study reported a 1-percent incidence of endophthalmitis after trabeculectomy with mitomycin.7

Antifibrosis agents are likely to in-duce a hypocellular or acellular bleb with less fibrovascular proliferation.8,9,10 Mitomycin produces filtering blebs that have a thinner and irregular epithelium, with fewer goblet cells and a more atrophic and avascular stroma. Full-thickness procedures are also more frequently complicated with late endophthalmitis than non-augmented trabeculectomies.11

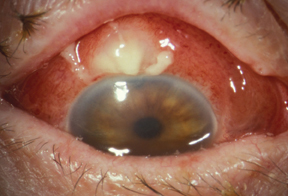

|

| Figure 2. Blebitis with decreased vision and pain prior to antibiotic therapy. |

• Bleb leaks are a predisposing factor for infection.7,13,14 The use of antifibrotic agents increases the incidence of bleb leaks after trabeculectomy. A thin bleb wall is probably associated with a higher risk of infection because of the transconjunctival spread of organisms and development of bleb leaks.

• Bacterial conjunctivitis and blepharitis have been associated with bleb-related endophthalmitis.15 A previous episode of blebitis is an important risk factor for post-trabeculectomy endophthalmitis.2 Releasable sutures have been linked to intraocular infection in sporadic cases.16

• Systemic diseases such us diabetes mellitus can make the patient more vulnerable to bleb-related ocular infections.2

Microbiology

The bacteria that cause bleb-related endophthalmitis almost certainly arise from the ocular flora, be they transient or permanent. Certain microorganisms such us Streptococcal species can spread through the intact conjunctiva17,14 and then enter the eye through the sclerostomy.

The most commonly involved organisms are the Streptococcal and staphylococcal species.18,19,15,20,14,4

There may be regional differences or changing patterns of infecting organisms responsible for blebitis.14 It's important to point out that organisms isolated from the ocular surface in patients with bleb-related endophthalmitis may differ from those responsible for an intraocular infection.15

Treatment

A recent survey among glaucoma specialists in the American Glaucoma Society reported different approaches to the treatment of blebitis, reflecting the lack of scientific evidence to guide our practice patterns.21

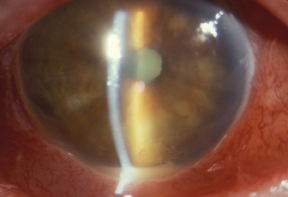

|

| Figure 3. Anterior chamber of eye in Figure 2 with acute blebitis. Subsequent evaluation of vitreous cells confirmed the diagnosis as endophthalmitis. |

In patients with blebitis (i.e., infection limited to the filtration bleb, without anterior chamber reaction), you can prescribe frequent topical application of a broad-spectrum antibiotic, with close supervision; for example, ofloxacin given every half hour to every hour. The patient can apply bacitracin ointment, which provides good coverage of gram-positive organisms, at bedtime. Oral antibiotics with high penetration into the eye (fluroquinolones: ofloxacin, moxifloxacin, or levofloxacin) is one current recommendation.22 Admission may not be necessary if you can see the patient daily.

If there is mild-to-moderate anterior segment reaction, treatment with fortified topical antibiotics around the clock and admission seems advisable. Combination of topical fortified cefazoline (50 mg/ml) or topical fortified vancomycin (25 mg/ml), and amikacin (50 mg/ml) or tobramycin

(14 mg/ml), would properly cover gram-positive and gram-negative microorganisms, respectively.

In patients with moderate-to-severe anterior chamber reaction, hypopyon and/or cellular reaction in the vitreous cavity (i.e., bleb-related ndophthalmitis), vitreous biopsy and intravitreal antibiotics are required, either through a pars plana injection or associated with a vitrectomy. A possible intravitreal antibiotic choice is 1 mg of vancomycin (10 mg/ml) and 400 mg of amikacin (5 mg/ml). Add oral antibiotics and hourly fortified topical eye-drops.

Vitrectomy, Corticosteroids and Bleb Revision

The role of pars plana vitrectomy and systemic antibiotics in the management of late endophthalmitis after glaucoma filtering surgery is not clear. A prospective, randomized clinical trial evaluating the treatment of postoperative bacterial endophthalmitis after cataract surgery showed that immediate vitrectomy wasn't necessary in patients with better than light-perception vision at presentation, but was of substantial help for those who had light-perception-only vision. Systemic intravenous antibiotic treatment wasn't helpful.23 However, it's unclear whether the preceding re-sults are applicable to bleb-related intraocular infections.

The effect of corticosteroids is unknown, and their use might be harmful. Therefore, we recommend starting topical steroids after the infection shows signs of improvement. The goal is to reduce the intense inflammation and prevent scarring of the bleb.

After resolution of the infection, the function of the filtration bleb may be impaired, requiring additional medication or surgical intervention, such as the implantation of a drainage device, for adequate pressure control.

The visual outcome is usually good in cases with blebitis and poor when the vitreous is involved, especially with virulent bacteria such as streptococcus, coagulase-positive staphylococci or gram-negative organisms. Coagulase-negative staphylococcal organisms (S. epidermidis) tend to have a more benign course.24,14,4

Prevention

Long-term antibiotic prophylaxis isn't recommended, as it seems to have no effect on the resident flora of the conjunctiva, may induce antibiotic resistance and may increase the risk of endophthalmitis.25 Another AGS survey showed that only a minority of the members (6 percent) routinely prescribed long-term antibiotic prophylaxis in filtered eyes.26

It seems reasonable, however, to use intermittent long-term therapy in some patients with high risk of bleb-related infection. Intermittent and alternating use of antibiotics with different spectra of coverage might minimize the development of drug-resistant organisms. Promptly treat conjunctivitis and blepharitis, and have the patient avoid soft contact lens wear.

Related ocular infection is essential to an early diagnosis and management. Previous bleb-related infection and monocular patients with bleb leaks may require more decisive treatment (e.g, surgical bleb revision).1

Current research is evaluating the role of novel anti-scarring agents that would improve the outcome of filtration surgery without the severe alteration of bleb morphology.27 One such agent is transforming growth factor beta2. Subconjunctival application of antihuman TGF-beta2 has been associated with a favorable outcome of filtration surgery, and is currently being evaluated in large randomized clinical trials.28

Marlene R. Moster, MD, is professor of Clinical Ophthalmology at Thomas Jefferson School of Medicine and is an attending surgeon on the Glaucoma Service, Wills Eye Hospital, Philadelphia. Contact her at (610) 949-9788; moster@willsglaucoma.org.

Augusto Azuara-Blanco, MD, PhD, is a consultant ophthalmic surgeon and Honorary Clinical Senior Lecturer at the Department of Oph-thalmology, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, University of Aberdeen in Aberdeen, United Kingdom. Contact him at +44 12 24 55 32 17; or aazblanco@aol.com.

1. Azuara-Blanco A, Katz LJ. Dysfunctional filtering blebs. Surv Ophthalmol 1998;43:93-126.

2. Lehmann OJ, Bunce C, Matheson MM, Maurino V, Khaw PT, Wormald R, Barton K. Risk factors for development of post-trabeculectomy endophthalmitis. Br J Ophthalmol 2000 Dec;84(12):1349-53.

3. The Fluorouracil Filtering Surgery Study Group: Five-year follow-up of the Fluorouracil Filtering Surgery Study. Am J Ophthalmol 121:349-366, 1996.

4. Wolner B, Liebmann JM, Sassani JW, Ritch R, Speaker M, Marmor M. Late bleb-related endophthalmitis after trabeculectomy with adjunctive 5-fluorouracil. Ophthalmology 98:1053-1060, 1991.

5. Greenfield DS, Suner I, Miller MP, et al.: Endophthalmitis after filtering surgery with mitomycin. Arch Ophthalmol 114:943-949, 1996.

6. Higginbotham EJ, Stevens RK, Musch DC, et al.: Bleb-related endophthalmitis after trabeculectomy with mitomycin C. Ophthalmology 103:650-656, 1996.

7. DeBry PW, Perkins TW, Heatley G, Kaufman P, Brumback LC. Incidence of late-onset bleb-related complications following trabeculectomy with mitomycin. Arch Ophthalmol 2002 Mar;120(3):297-300.

8. Hutchinson AK, Grossniklaus HA, Brown RH, et al.: Clinicopathologic features of excised mitomycin filtering blebs. Arch Ophthalmol 112:74-79, 1994.

9. Mietz H, Arnold G, Kirchhof B, et al.: Histopathology of episcleral fibrosis after trabeculectomy with and without mitomycin C. Graefe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 234:364-368, 1996.

10. Nuyts RM, Felten PC, Pels E, et al.: Histopathologic effects of mitomycin C after trabeculectomy in human glaucomatous eyes with persistent hypotony. Am J Ophthalmol 118:251-253, 1994.

11. Sastry SM, Street DA, Javitt JC: National outcome of glaucoma surgery: complications following partial and full-thickness filtering procedures. J Glaucoma, 1:137-140, 1992.

12. Caronia RM, Liebmann JM, Friedman R, et al.: Trabeculectomy at the inferior limbus. Arch Ophthalmol 114:387-391, 1996.

13. Soltau JB, Rothman RF, Budenz DL, Greenfield DS, Feuer W, Liebmann JM, Ritch R. Risk factors for glaucoma filtering bleb infections. Arch Ophthalmol 2000 Mar;118(3):338-42.

14. Waheed S, Ritterband DC, Greenfield DS, Liebmann JM, Seedor JA, Ritch R. New patterns of infecting organisms in late bleb-related endophthalmitis: a ten year review. Eye 1998;12 ( Pt 6):910-5.

15. Mandelbaum S, Forster RK, Gelender H, Culbertson W: Late onset endophthalmitis associated with filtering blebs. Ophthalmology 92;964-972, 1985.

16. Burchfield JC, Kolker AE, Cook SG: Endophthalmitis following trabeculectomy with releasable sutures. Arch Ophthalmol 114:766, 1996.

17. Katz LJ, Cantor LB, Spaeth GL: Complications of surgery in glaucoma. Early and late bacterial endophthalmitis following glaucoma filtering surgery. Ophthalmology 92:959-963, 1985.

18. Ciulla TA, Beck AD, Topping TM, Baker AS. Blebitis, early endophthalmitis, and late endophthalmitis after glaucoma-filtering surgery. Ophthalmology 1997 Jun;104(6):986-95.

19. Kangas TA, Greenfield DS, Flynn HW Jr, et al.: Delayed-onset endophthalmitis associated with conjunctival filtering blebs. Ophthalmology 104:746-752; 1997.

20. Phillips WB, Wong TP, Berger RL, et al. Late-onset endophthalmitis associated with filtering blebs. Ophthalmic Surg 1994; 25:88-91.

21. Reynolds AC, Skuta GL, Monlux R, Johnson J. Management of blebitis by members of the American Glaucoma Society: a survey. J Glaucoma 2001 Aug;10(4):340-7.

22. Fiscella RG, Nguyen TK, Cwik MJ, Phillpotts BA, Friedlander SM, Alter DC,

Shapiro MJ, Blair NP, Gieser JP. Aqueous and vitreous penetration of levofloxacin after oral administration. Ophthalmology 1999 Dec;106(12):2286-90.

23. Anonymous: Results of the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. A randomized trial of immediate vitrectomy and of intravenous antibiotics for the treatment of postoperative bacterial endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol 113:1479-1496, 1995.

24. Poulsen EJ, Allingham RR. Characteristics and risk factors of infections after glaucoma filtering surgery. J Glaucoma 2000 Dec;9(6):438-43.

25. Jampel HD, Quigley HA, Kerrigan-Baumrind LA, et al. Risk factors for late-onset infection following glaucoma filtration surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001 Jul;119(7):1001-8.

26. Wand M, Quintiliani R, Robinson A. Antibiotic prophylaxis in eyes with filtration blebs: survey of glaucoma specialists, microbiological study, and recommendations. J Glaucoma 4:103-109, 1995.

27. Cordeiro MF, Gay JA, Khaw PT. Human anti-transforming growth factor-beta2 antibody: a new glaucoma anti-scarring agent. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999; 40:2225-34.

28. Siriwardena D, Khaw PT, King AJ, et al. Human antitransforming growth factor beta(2) monoclonal antibody--a new modulator of wound healing in trabeculectomy: a randomized placebo controlled clinical study. Ophthalmology. 2002 Mar;109(3):427-31.