Surgeons are still hard at work trying to devise a consistent way to treat presbyopia with corneal refractive surgery. Though the physicians working on the problem say their procedures have moved beyond the problems of multifocal corneas and intraocular lenses, there is still skepticism from some in the refractive surgical community about the treatments' effectiveness, and the results are still very preliminary. In this article, Review looks at the strengths and weaknesses of two approaches to presbyopic LASIK.

New Approaches?

Saudi Arabian surgeon Alaa El Danasoury is working on a presbyopic LASIK technique with the Nidek laser that he thinks avoids or minimizes the problems inherent with multifocal corneas.

His treatment involves ablating in the corneal periphery for near vision, and then treating the center for distance.

"A treatment consists of three stages," explains Dr. Alaa. "The first is to correct any hyperopia or myopia. Next, we do a hypermetropic treatment to create the peripheral zone for near vision at around 7 mm with a 10 mm transition zone. The third step is to compensate for this peripheral treatment with a central myopic treatment in 3.5-5 mm of the center." As an example, he says if he were correcting for +2 D of presbyopia at the 7-mm and 10-mm zones, he'd compensate by first doing a treatment at 3.5 mm with a transition zone to 4.5 mm, and then a second treatment at 4 mm with a transition zone to 5 mm.

But is this still a multifocal approach?

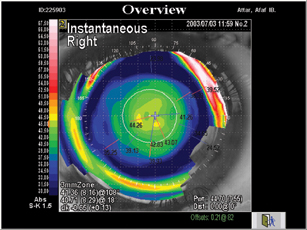

"We actually believe that this isn't a multifocal treatment," he says. "Instead, it's kind of an aspheric ablation. We learned from our experience with multifocal IOLs that there is almost always a loss of contrast sensitivity and a compromise between near and far vision. In the case of our treatment, we haven't seen this compromise, we think because of the aspheric ablation of the cornea. If you look at the postop topography of these patients compared to conventional LASIK, it's very difficult to notice a difference. The key is to use a relatively high number of steps, which we can do easily with the Nidek."

|

| Saudi Arabia's Alaa El Danasoury, MD, ablates a peripheral near ring, leaving the center for distance. |

The procedure continues to be a work in progress. "We don't know exactly how much of the presbyopia we should aim at correcting," says Dr. Alaa. "It's a dynamic and changing condition. We don't know the best approach to correct +2 D of presbyopia; right now we tend to overcorrect somewhat, but we don't know if this is the best thing to do."

Bogota, Colombia's Gustavo Tamayo, MD, is also working on a treatment for presbyopia in pure presbyopes and myopic presbyopes. He also hopes his approach is different from the multifocal corneas created by presbyopic LASIK in the past.

His technique, like Dr. Alaa's, also involves a peripheral near vision zone. The peripheral zone usually runs from 6 to 9 mm and involves removing between 25 and 40 µm of tissue (+1 D to +3 D treatment). The center 6 mm is for distance.

"Our treatment still doesn't approach the presbyopic hyperope yet," says Dr. Tamayo. "This is because the treatment for hyperopia is in the periphery, so we don't feel confident enough treating over the previous hyperopic treatment."

Though the treatment would appear to use multiple zones, Dr. Tamayo insists that it's not a true multifocal treatment.

"Our treatment isn't a true multifocal one insofar as it doesn't touch the center," he says. "So, we're not really making a multifocal ablation. There are some patients that complain a bit about glare initially, but this decreases with time. But the most important thing is that we've found that none of our patients have lost any lines of best-corrected vision, which is important in terms of the safety of the procedure."

Though Dr. Tamayo's results are preliminary (10 presbyopes) and only have six months of follow-up, he says about three-quarters of the patients see between J1 and J3 at near. He says it works best in patients around 55. None lost any best-corrected vision.

Dr. Tamayo says the treatments do cause some optical aberrations, but that they're "so far in the periphery, at 7 mm or more, that we don't see a loss of contrast sensitivity or lines of best-corrected vision."

A Skeptical View

Houston surgeon Jack Holladay agrees that a prolate aspheric ablation would be a good approach to giving patients a better depth of field for reading, but thinks that ablating a peripheral zone and leaving one in the center for distance is just another kind of multifocal cornea patterned after similar unsuccessful multifocal IOLs.

"The Iolab company originally made a bull's-eye IOL, with the center for near and the periphery for distance," Dr. Holladay says. "Then, IOL companies went to an annulus [with near vision in a peripheral annulus and distance in the center], then to the Array and the diffractive IOL … all of them reduce contrast sensitivity. The reason the annulus doesn't work well is because when the patient looks up close to read at near, his pupil constricts and gets inside the annulus that he needs for near vision. And, at night, when he walks outside and wants to look in the distance, that annulus is right down the barrel of where he's looking, so he gets a dramatic loss of contrast and sees halos around lights."

He says that, though every kind of multifocal lens is available in contact lenses, too, from bull's-eyes to annuli, only 5 percent of contact lens wearers choose them. "If it were that great a concept, we wouldn't have only 5 percent of contact lens wearers in multifocal contact lenses and 10 percent in monovision," he argues. "Eighty-five percent still wear readers because they'd rather have crisp vision at other distances."

He says that one ablation strategy that has potential for presbyopes is a variation on a theme that he has advocated repeatedly: the prolate cornea.

"Since hyperopic treatments accidentally undercorrect in the periphery, patients often get better near vision," he says, because they are exaggerated prolate (Q-value is -0.5 or more negative). "If the cornea's of myopes were made exaggerated prolate, we'd see the same benefit."

Until companies and surgeons move in that direction, though, Dr. Holladay says things will be "the same story 15 years later … it's the same for corneal presbyopic surgery as it was for multifocal IOLs, which came 15 years after multifocal contacts. But, the experience on the cornea is going to be identical and even a little worse because you can't control [the zones] as well due to corneal healing and you can't, unlike contacts, do a couple lens changes to get it working right for a particular patient."