How many times have you been confronted by an iris that either prolapses or threatens to prolapse during cataract surgery? As any surgeon will tell you, once is too often. So: Are there reliable strategies you can use to stop it from recurring? The answer is yes—but not always. Think about the many risk factors you need to consider while managing the intense complexity of a 10-to-20-minute operation on eyes that vary widely anatomically and in terms of intraoperative responses.

“Just being aware of all the risk factors is the most significant precaution you can take preoperatively for patients who are predisposed to iris prolapse,” says Audrey R. Talley-Rostov, MD, a partner at Northwest Eye Surgeons in Seattle. “Beyond that, there’s not a lot that you can do, per se, until you begin the surgery. We need to be prepared to respond to a lot of possible challenges, some much bigger than others.”

In this report, surgeons with a track record of decades of experience in understanding and controlling this common complication will explain how they identify and manage risk factors, implement time-proven preventive measures and effectively respond to acute episodes in the management of iris prolapse.

|

Game Planning Wisely

Most surgeons group risk factors of iris prolapse into two categories—pre-existing and intraoperative. The most common pre-existing factor is a patient’s history of taking alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonists (so called alpha-blockers), which can cause intraoperative floppy iris, as first described in a 2005 study by John R. Campbell, MD, and David F. Chang, MD.1

The major uses of alpha-blockers are for treatment of hypertension and symptomatic benign prostatic hypertrophy, although the primary agent prescribed for men with BPH—tamsulosin (Flomax, Boehringer Ingelheim)—can also help women experiencing difficulty passing urine, as well as female and male patients struggling to pass large kidney stones. Other alpha-blockers used for BPH therapy include terazosin (Hytrin), doxazosin (Cardura), alfluzosin HCL (Uroxatral) and silodosin (Rapaflo).

These agents bind to and inhibit type 1 alpha-adrenergic receptors and thus inhibit smooth muscle contraction, compromising the dilator muscle in the patient. The result can be a floppy, billowing iris accompanied by progressive miosis during cataract surgery, with the iris threatening to prolapse through the tunnel and side-port incisions.

Even years after a patient stops taking one of these medications, surgeons note, the patient remains at risk for developing the manifestations of intraoperative floppy iris syndrome.2

Up to 90 percent of men develop BPH by their 70s or 80s,3 a fact that should significantly increase your concern when screening patients.

“Knowing if your patient has any history of taking these medications is very important, obviously, but confirming this history can sometimes be very challenging, as we all know,” says Kavitha R. Sivaraman, MD, a partner at the Cincinnati Eye Institute and a clinical assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of Cincinnati. “If they’re poor dilators preoperatively, I will ask them if they have ever taken Flomax or any of these other medications. A lot of times, they don’t remember. A look at their current medications to see if any of them are for the treatment of prostate issues can clue you in to a potential risk factor. Or you can ask patients if they have had past prostate issues, which they should remember, and that will help you identify them.”

Besides sleuthing for evidence of past alpha-blocker usage, Dr. Talley-Rostov looks for a history of trauma, pseudoexfoliation and, like her colleagues, a pupil that doesn’t dilate well, even absent any reported alpha-blocker usage. “We should also be vigilant in patients who’ve undergone previous ocular surgery, specifically any procedure creating iris transillumination defects,” she says. “In addition, remain alert for a previous infection with herpes-zoster disease, a history of uveitis or previous inflammatory disease. All are risk factors.”

Robert Weinstock, MD, director of cataract and refractive surgery at the Eye Institute of West Florida, in Largo, looks for a patient with a shallow anterior chamber, as might be found in highly hyperopic patients. “I also check for a history of peripheral laser iridotomy, which tends to damage the iris. Patients with lightly colored eyes also suggest the possibility of anatomical muscular weakness of the iris.”

Samuel Masket, MD, in practice in Los Angeles, carefully evaluates patients with a crowded anterior segment. “You can see lenses that are particularly thick and a small corneal diameter,” he notes. He urges you to also be aware of the increased risk associated with distinct types of crowded anterior segments, typically present in small hyperopic eyes, as follows:

- microphthalmos, characterized by a small corneal diameter and small anterior and posterior dimensions;

- relative anterior microphthalmos, which involves (even in some myopic patients) an eye of normal anatomic length but a small anterior segment; and

- nanophthalmos, a rare condition, often confused with microphthalmos, characterized by a thickened sclera, a normal-sized anterior segment and a very foreshortened back of the eye.

He also pays attention preoperatively to external forces that may put pressure on the eye. This increase in pressure could be caused by a lid speculum; a thick neck; and elevated episcleral venous pressure in the upper part of the body. The latter factors are often associated with congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Retrobulbar anesthesia is another risk factor, potentially leading to a hemorrhage in the orbit, which induces posterior pressure that pushes on the eye, increasing the risk of iris prolapse, says Dr. Masket.

Intraoperative Risk Factors

|

Intraoperative risk factors may or may not be associated with IFIS or other pre-existing risk factors. Once you begin surgery, Dr. Weinstock cautions against making a wound that’s too posterior or steep, with a short tunnel into the anterior chamber, particularly in a patient with a pre-existing risk factor.

“A wound that’s too large or wide is also ill-advised, potentially allowing leakage and room for the iris to prolapse in the presence of a phaco needle with a lot of play in the wound,” he says.

Dr. Sivaraman agrees. “I always pay special attention to wound architecture,” she says. “I want to create a true triplanar incision of the appropriate length. A very short wound will also predispose to iris prolapse.” In addition, inadvertently contacting the iris with the phaco needle can complicate surgery, damaging the iris and making it more likely to prolapse from the mechanical trauma that occurs, according to Dr. Weinstock. Such a mishap is more of a risk in the smaller anterior segments that Dr. Masket mentions.

|

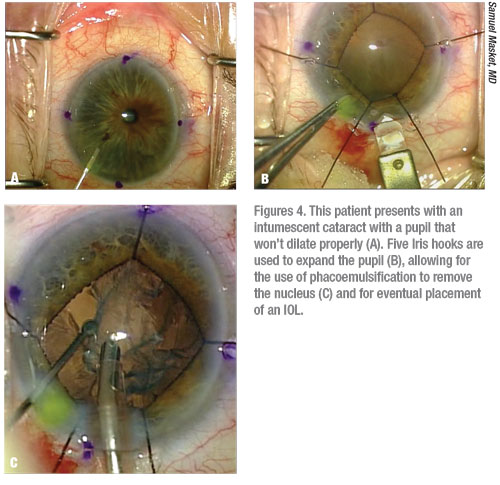

Aside from avoiding problems created by poorly structured wounds and a stray phaco needle, you should do certain things if you think you have a patient who’s prone to iris prolapse, Dr. Weinstock continues. “Pupil size management is very important,” he says. “In a patient who’s been exposed to tamsulosin, I recommend that you use a Malyugin Ring to minimize intraoperative miosis. Or you could use three, four, five or even six iris hooks to pull the iris back and out of the way, where you can hold it still so it won’t make contact with your phaco needle.”

Dr. Talley-Rostov routinely performs small incision bi-manual cataract surgery, which, besides serving as her preferred technique, minimizes the risk of iris prolapse. “I do everything through two 1.3-millimeter incisions,” she says. “And then I expand the incision for the IOL insertion. By working with two very small incisions, I can usually maintain fluidics that reduce the incidence of iris prolapse. If necessary, I can also lower the flow, which is important.”

All things considered, Dr. Weinstock notes that even the best surgeons can make a bad surgical wound. “If right out of the gate this happens during your surgery, you can suture that inappropriately-sized wound shut and make a fresh wound,” he points out. “Or, if the wound is just too wide, you can put a suture through the edge of the wound that tightens it up just in that region. That creates a more controlled wound for your phaco needle to go through without all of that play on the side, which could allow the iris to get out.”

Right Solutions

Dr. Weinstock notes that phenylephrine and ketorolac intraocular solution (Omidria, Omeros) helps manage at-risk patients if you put it in the BSS bottle before starting the case. The solution provides a constant stream of dilating and anti-inflammatory agents throughout the case, limiting pupillary constriction and intraoperative floppy iris problems, he notes.

Because some payers don’t cover the cost of this prophylactic treatment, some surgeons use alternative solutions. “I rely on intracameral Shugarcaine solution (epinephrine 0.025% and lidocaine 0.75%) in a fortified balanced salt solution,” says Dr. Sivaraman. “I tend to use it even for a tamsulosin patient who doesn’t have dilation problems. I’ve never regretted using it.”

The Shugarcaine solution, introduced by the late Joel K. Shugar, MD, MSEE, features one part sulfite-free, preservative-free epinephrine mixed with three parts Shugarcaine (unpreserved lidocaine diluted 1:3 with balanced salt solution), designed to spare endothelial cells damage because the pH of the mixture measures 6.90, well above the minimum safe threshold of 6.50.4

Another solution used for this purpose is cyclopentolate 0.1%, phenylephrine 1.5% and lidocaine 1% (intracameral Lundberg and Behndig’s dilation solution). In her experience, however, Dr. Talley-Rostov says the use of sufficiently diluted simple intraocular preservative-free epinephrine can be very helpful.

“A lot of surgeons use these mixtures as an adjunct to Omidria, or as a substitute for Omidria,” says Dr. Weinstock. “Surgeons will use them when they begin hydrodissection or right when they enter the eye, if the pupil is small. The solutions provide another form of pharmacotherapy that can be used intraoperatively to control the patient’s pupil.”

For any patient with an established history of intraoperative floppy iris syndrome, Dr. Masket also administers atropine 1%, t.i.d. for two days before surgery, enhancing the effect of intraoperative intracameral epinephrine, as validated in a 2007 study he led.5 “Although this preoperative treatment is very effective, you have to keep two important issues in mind,” he says. “Number one, the logistics of beginning the therapy two days before surgery, when ophthalmologists typically don’t see the patient, has to be coordinated,” he says. “The second important point is patients often think they should stop taking tamsulosin in advance of surgery. Doing this can create a low but serious risk of acute urinary retention, which obviously needs to be avoided. I emphasize in the strongest terms to my patients that they need to continue taking their tamsulosin while taking preoperative atropine.”

|

All About Pressure

“Safeguarding the iris is also all about controlling pressure,” says Dr. Sivaraman. “If the pressure in the eye is high, the iris is going to come out. The iris is going to follow the pressure gradient. This typically happens a lot during hydrodissection. So after I make my capsulorhexis, I burp out quite a bit of that viscoelastic. When I do cortical-cleaving hydrodissection, I use small bursts and decompress the lens—meaning I push the lens down and let the fluid come out around it. The pressure building up in the eye is a very common cause of this problem. Decompress the pressure inside of the eye until it equals the atmospheric pressure outside of the eye.”

Dr. Weinstock agrees. “Any time you raise eye pressure, it’s going to be pushing out because the fluid has to escape somewhere,” he says. “A floppy iris is also going to be forced out of the eye, as it would be after any other trauma. Also, at the end of the surgery, when you’re hydrating the wound and sealing the eye, you can overinflate it and then have a sudden burp under heavy pressure. The iris can pop out of the eye.”

In eyes with overcrowded anterior segments, Dr. Masket says he prepares for the need to reduce the volume of the vitreous when posterior pressure increases. “I recommend the use of mannitol, 0.5 to 1 gram per kilogram of body weight, or if necessary, prophylactic removal of a small amount of vitreous via pars plana vitrectomy,” he says. “First and foremost, however, I strongly recommend my dosing level of mannitol, which I think ophthalmologists often use in doses that are too low and inadequate.”

Besides increased vitreous pressure as a cause of rising IOP, Dr. Talley-Rostov considers all other potential causes. “The pressure could be increasing because the patient has to go to the bathroom, or is holding his or her breath and experiencing a Valsava-like effect. We also look for high blood pressure and see if the patient’s in pain. We can administer IV lidocaine or pain medication, if we have established IV access preoperatively. Verbal assurance can help reduce pressure in anxious patients. If I find the problem is truly increased IOP and I see the start of an iris prolapse, I’m thinking the patient is at risk for a choroidal hemorrhage. I can use mannitol, of course, but I find the quickest way to reduce IOP acutely in the OR is to provide IV lidocaine, which lowers high IOP very quickly.”

The Role of Viscoelastics

Dr. Weinstock uses viscoelastics, such as Viscoat (Alcon), Healon5 (Johnson & Johnson Vision) and OcuCoat (Bausch + Lomb) to help manage the intraoperative risk of iris prolapse. The cohesive and dispersive properties of these OVDs create an effective adjunct to surgery, he says. “A mechanical agent is effective at pushing the iris down and away from the wounds,” he says. “It provides space in the eye, which I find helpful. These are great tools for when you’re about to operate on an at-risk patient or when you get into trouble during surgery.”

However, the dispersive component stays in the eye longer, he cautions. “The biggest risk is that it stays in the eye and then causes postop pressure spikes,” he notes. “So you have to make sure you evacuate all of the OVD solution with irrigation and aspiration.”

Dr. Masket, however, only uses a cohesive viscoelastic when operating on a patient at high risk for iris prolapse. “The dispersive agents tend not to maintain space well and are very tissue-protective,” he says. “The problem is that in certain situations, as the agent comes out of the eye, it tends to bring that tissue with it. So in the case of a crowded anterior segment, positive pressure in the eye or IFIS, I don’t recommend the use of dispersive agents. I recommend the use of cohesive agents. That’s a very important point and most ophthalmologists aren’t aware of it. But I learned it the hard way over a long career.”

Dr. Talley-Rostov acknowledges that some surgeons find OVDs such as Healon5 helpful for managing iris prolapse, but she’s not one of them. “I tried this a while ago and found that, in my hands, it was not exceedingly helpful,” she says. “I instead prefer to use a Malyugin ring and iris hooks, while using OVD as a cohesive or viscoadaptive agent, as needed. But I find Healon5 is hard to get out of the eye and can contribute to a risk of increased IOP postop. You have to make sure you irrigate it out. Otherwise, you can see a temperature increase, risking a wound burn.”

Responding to a Prolapse

Dr. Masket watches for the globe getting firm right before an iris prolapse. “A common mistake is for the surgeon to try to add more OVD through the main incision, pushing on the iris,” he says. “That will only tend to make holes in the iris.”

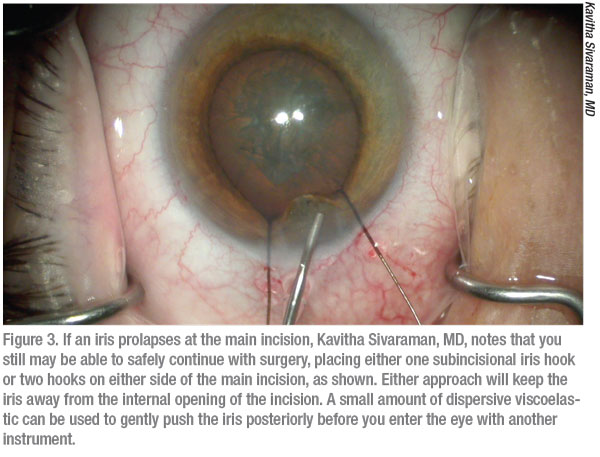

If the iris prolapses, he recommends that you remove some of the fluid pressure from the paracentesis, using bimanual I/A or single-port aspiration, allowing you to reduce the internal pressure in the eye and bring the iris back in through the port. “Sometimes you can do it externally,” adds Dr. Masket. “But do not—I repeat—do not push the iris through the main incision. The best approach is to soften the eye and then, if the iris doesn’t go back in, it might be caught on the lip of the wound. You can massage over the external aspect of the incision, not the iris itself. If that doesn’t bring the iris in, then sweep it in through another sideport.” Even in this situation, Dr. Masket again warns against pushing on the iris, since doing so could create holes in it rather than settling it back into the eye.

To be as gentle as possible on a prolapsed iris, Dr. Weinstock recommends that you go through a secondary wound and completely shallow the chamber.

Unlike many of his colleagues, Dr. Weinstock will gently push on the iris at times. “Depending on where the iris is, you may be able to use a Kuglen hook, phaco needle, I/A tip or viscoelastic to gently push on it and—again, only if the eye is soft—the iris will go back into the eye,” he says.

An alternative approach is to make sure only a small amount of fluid remains in the eye, then approach the iris with a side paracentesis and sweep it back into the eye, according to Dr. Weinstock. “It would be very difficult to go into a secondary wound with an instrument if the chamber is completely shallowed,” he notes. “So if you’re going to go sweep the iris back into the eye, you need to have some chamber depth.”

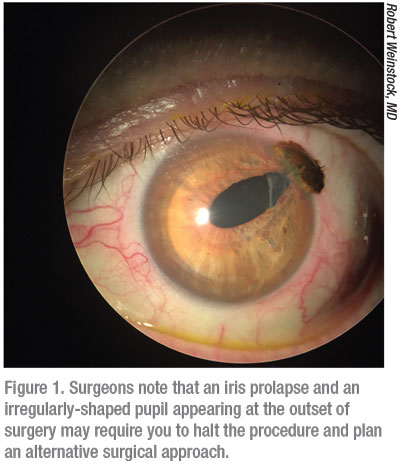

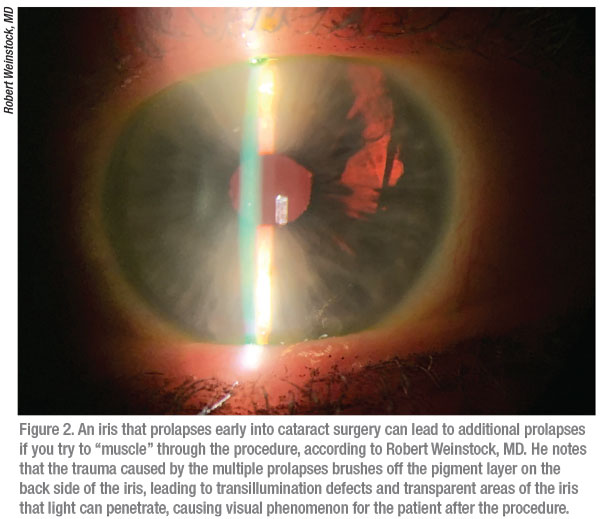

An iris prolapse early in the procedure raises the greatest risks. “After you’ve drawn a prolapsed iris back into the eye, the risk of recurrent prolapses increases,” notes Dr. Weinstock. “Every time it prolapses as you continue with surgery, the trauma of the prolapse brushes off the epithelial pigment layer on the back side of the iris, some of its most fragile tissue,” says Dr. Weinstock. “Then you get transillumination defects and transparent areas of the iris that light can penetrate because of the loss of pigment. Patients affected by these issues can notice visual phenomenon after surgery.”

An even worse development can occur if the trauma of repeated prolapses damages the sphincter muscle of the iris.

“With this problem, your patient will be left with an irregular pupil, and that can affect the optics and vision and can also be a cosmetic issue,” Dr. Weinstock says. “That’s probably one of the most severe and worrisome aspects of iris prolapse during surgery. Remember that if you leave the iris prolapse and continue to phaco, the phaco needle-—with the iris prolapsed around or under it—is continually rubbing the iris and damaging the tissue because this tissue is so fragile. You have to be careful to avoid a permanent trauma to the iris sphincter or the loss of iris tissue.”

Another important consideration is that the fibers that make up the iris surface can be very filamentous. “If you touch or damage the iris, those little strands want to come out of the wound, and it can be hard to get them to stay back in the eye,” says Dr. Weinstock. “This is also more of a problem in light-colored eyes.” He notes that acetylcholine chloride (Miochol–E) or carbachol (Miostat) can help in these cases by shrinking the pupil and pulling the iris away from the wound.

All Things Considered

Surgeons say there seemingly is no end to the considerations to keep in mind to avoid and manage iris prolapses, which is why no surgeon has ever been able to prevent them entirely. “Quite simply, iris prolapse occurs when you have a discontinuity in pressures between the outside of the eye and the inside of the eye,” says Dr. Masket. “So many things can potentiate this discontinuity that it will always be a concern during surgery.” REVIEW

Dr. Talley-Rostov is a consultant for Alcon and Bausch + Lomb. Dr. Weinstock is a speaker for Bausch + Lomb. Drs. Sivaraman and Masket have no financial interests in any of the products or companies mentioned in this article.

1. Chang DF, Campbell JR. Intraoperative floppy iris syndrome associated with tamsulosin. J Cataract Refract Surg 2005; 31:664–673.

2. Lunacek A, Badereddin MAA, Christian Radmayr C, et al. Ten years of intraoperative floppy iris syndrome in the era of alpha-blockers. Cent European J Urol 2018;71:1:98-104

3. Roehrborn CG. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: An overview. Rev Urol 2005;7:Suppl 9: S3–S14.

4. Slack JW, Edelhauser HF, Helenek MJ. A bisulfite-free intraocular epinephrine solution. Am J Ophthalmol 1990;110:77-82.

5. Masket S, Belani S. Combined preoperative topical atropine sulfate 1% and intracameral nonpreserved epinephrine hydrochloride 1:4000 [corrected] for management of intraoperative floppy-iris syndrome. J Cataract Refract Surg 2007;33:4:580-2.