As clinicians, we’re problem solvers. Today, we have many tools we can use to manage glaucoma and help preserve our patients’ vision, so one question we constantly strive to answer is: Which tools are the right ones for solving this patient’s problem? And, how many of those tools should we use to get the best possible outcome?

Topical medications remain a mainstay of glaucoma treatment, and today we have more varieties to choose from than ever before. Currently, seven classes of compounds are available:

• prostaglandin analogues, including a nitric-oxide-donating prostaglandin (instilled once a day);

• rho kinase inhibitors (once a day);

• beta blockers (once a day);

• alpha agonists (two or three times a day);

• carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (two or three times a day);

• miotics (one to four times a day); and

• nonselective adrenergic agonists (twice a day).

For most patients, topical drops are a less-risky way to manage glaucoma than traditional surgeries such as trabeculectomy and tube shunt implantation. For that reason, most surgeons would agree that if drops can control the disease, prevent progression and be consistently administered and tolerated by the patient, then that’s the option of choice. (MIGS surgeries, now added to our treatment options, need to be carefully assessed in comparison to medical management, in terms of efficacy and side effects, for each individual patient.)

This proliferation of glaucoma drugs, particularly with the recent addition of new medications—the nitric-oxide-donating prostaglandin Vyzulta, which is a co-drug, and the rho kinase inhibitor Rhopressa (as well as the fixed-dose combination of netarsudil and latanoprost, Rocklatan)—has raised important questions: How many medications should we be asking our patients to use? How many will be well-tolerated? And how many will be effective?

Multi-drop-related Issues

Asking patients to use multiple drops raises a host of potential concerns, ranging from how well the drops will perform when added to an existing regimen, to how managing multiple drops will affect compliance. Here’s what we know about these issues, based on the published literature:

• You won’t get as much pressure reduction when using a drop as a second or third medication. When we use a drug by itself, we have a pretty good idea how much IOP reduction we’ll get. For example, with beta blockers alone you’ll probably get a 25 to 28 percent IOP reduction. But if you add a beta blocker to latanoprost as a second medication, the effect will be smaller. In short, the second, third and fourth drugs in a patient’s regimen won’t give you the same bang for the buck that you’d get using them first-line. We’ve seen this in randomized clinical trials, typically Phase III, usually comparing one medication to another (often timolol).1

• The beneficial effect of a se-cond, third or fourth medication may not last. Data in the literature suggests that the effect of an added medication wanes over time.2 How-ever, it’s important to note that this conclusion is based on data from a population of patients; an individual patient may not mirror these findings. For that reason, treating each patient is somewhat trial and error. You pre-scribe a drug and see if it works, and if so, how long it works. Whatever the outcome, your next patient could have a different reaction.

• A complex regimen with mul-tiple medications may undercut compliance. Many patients will find it frustrating to manage multiple medications; some will simply find it difficult to remember to take them. Other possible issues include the increased cost associated with more medications, side effects that patients dislike and the age of the patient. Young patients who don’t take many pharmaceuticals may not take the regimen as seriously as they should. Older patients may have mental status changes or difficulty instilling the drops. In addition, we know that level of education and health literacy can be barriers to compliance.3

• Nocturnal efficacy can be an issue. Overnight studies involving glaucoma drugs have revealed that several classes of compounds are less effective at night than during the day.4 That lack of efficacy at night may lead to progression in patients who appear to be well-controlled in daytime office IOP measurements. For that reason, when we design a regimen, we have to make sure we include medications that work at nighttime as well as during the day. Furthermore, if there’s any question that progression is occurring, it’s important to consider the possibility that the progression may be due to nocturnal IOP fluc-tuation. If so, reorganize the regimen to make sure that nighttime IOP is being addressed.

• Chronic medical therapy may lead to conjunctival changes and ocular surface disease. This happens, in part, as a result of inflammation of the conjunctiva. We know the changes can be related to the preservatives, the drugs them-selves and/or the frequency of dosing. These conjunctival changes can have multiple consequences, including visual blurring and discomfort for pa-

tients.5 They may also lead to a re-duced rate of success in subsequent incisional surgery.6 So, the fewer drops we can prescribe and still prevent pro-gression, the better.

Despite the caveats just mentioned, it’s clear that clinicians treating glaucoma use all the treatment op-tions available. We can see this in the literature. Patients enrolled in the AGIS trial, which was conducted before the advent of prostaglandins, alpha adrenergic agonists and topical CAIs, were on a mean number of 2.7 medications at baseline enrollment.7 In the mid-90s, those three classes of compounds were approved; the num-ber of baseline medications in similar patient populations participating in subsequent clinical trials was more than three.8,9 Current peer-reviewed articles and case reports confirm even higher numbers of baseline medications—3.6 up to as many as five.10-12 So despite being aware of the limitations of multiple drops, we still tend to use a good number of medications in patients when we believe they need them to lower IOP.

|

Third and Fourth Drops

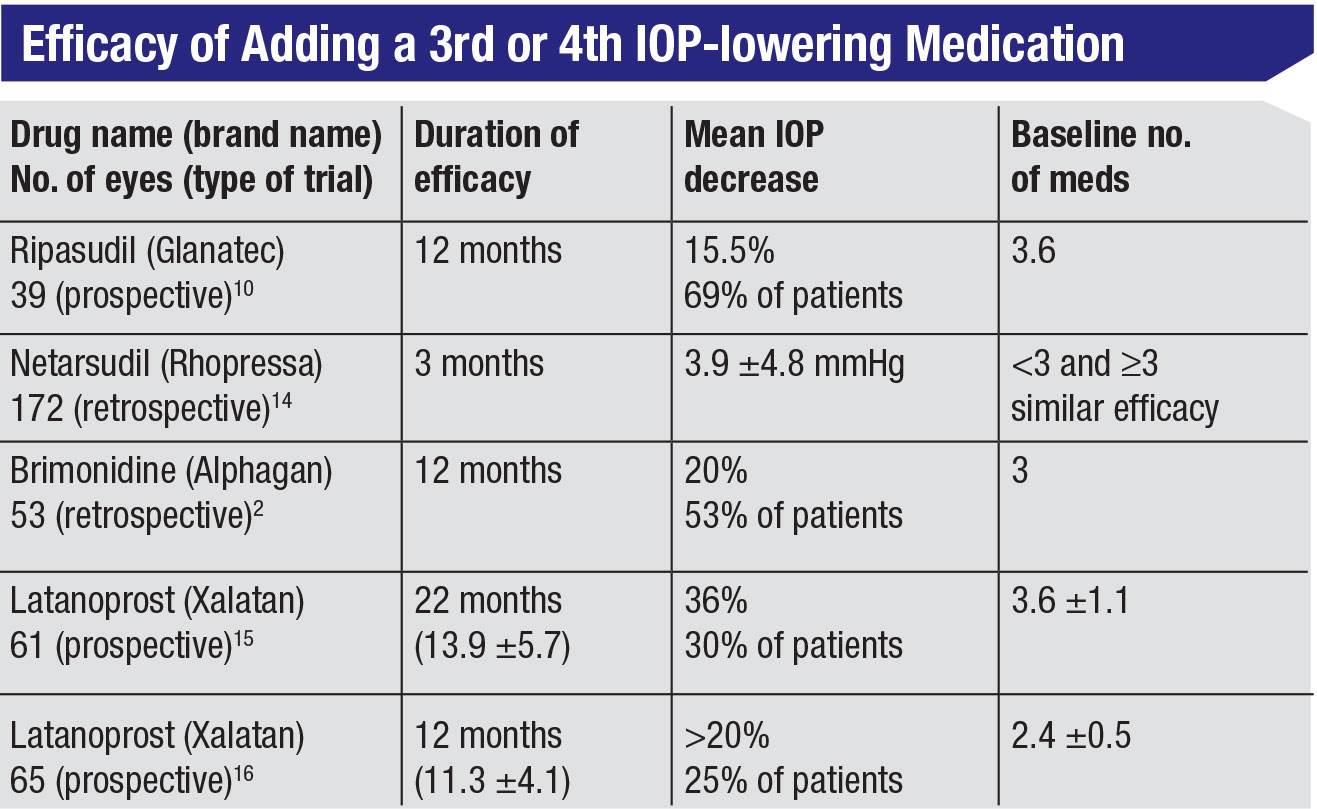

That being said, what do we know about adding a third or fourth medication to a patient’s regimen? A few studies in the literature have addressed this question. (See table, above.) For example:

• One prospective, 12-month study conducted in Japan monitored the effect of Ripasudil (a rho kinase inhibitor drop administered twice a day that’s only available in Japan) when added to the regimens of patients with a mean baseline of 3.6 medications. This was the fourth or fifth medication for some of these patients, but more than two-thirds of them had an additional IOP reduction of almost 16 percent.10

• A retrospective 12-month study in which brimonidine was added to a baseline regimen of three medications found that slightly more than half of the patients had an additional 20-percent reduction in IOP.2

• Another study followed 172 eyes for three months after netarsudil was added to baseline regimens. The result was an additional mean pressure reduction of about 4 mmHg. Of note, the efficacy of the addition of netarsudil was similar, regardless of whether patients were on fewer or more than three medications at baseline.13

• Several prospective studies have looked at adding latanoprost to patients already on anywhere from 2.4 to 3.6 medications.14,15 In these studies, additional IOP reductions were observed, ranging from a little more than 20 percent to 36 percent. However, this was only observed in a minority of patients (25 to 30 percent). So, latanoprost didn’t provide as robust an additional IOP reduction as had been anticipated.

What about using fixed-combination drops as third and fourth medications? We know that fixed-combination regimens may help address efficacy, compliance and surface toxicity. It turns out that they may also reduce intra-day and inter-day IOP fluctuations,16 which may contribute to progression.17 This could be the result of better compliance, since fewer drops need to be managed, or the result of eliminating the issue of the second drop washing out the first drop if the second is instilled too quickly after the first. (This is obviously not a concern with a combination drop.)

Today we have several fixed-dose combination therapies available in the United States:

1. a fixed-dose combination of netarsudil and latanoprost, (Rocklatan, approved 2018)

2. a fixed-dose combination of brinzolamide and brimonidine (Simbrinza, approved 2013)

3. a fixed-dose combination of a topical CAI and a beta blocker (Cosopt, approved 1998);

4. a fixed-dose combination of brimonidine and a beta blocker (Combigan, approved 2007); and

5. the co-drug latanoprostene bu-nod, a nitric-oxide-donating prostaglandin (Vyzulta, approved 2017).

In addition, several prostaglandin agonist/beta blocker combinations are commercially available outside of the United States (for example, Xalcom).

The challenge we face is that there are few—and only retrospective—studies to date involving the additivity of the newer combination drugs to existing regimens.13,18 Of course, we do know a fair amount about their use as single agents from the numerous phase III clinical trials that have been published.19-21

Counting the Drops

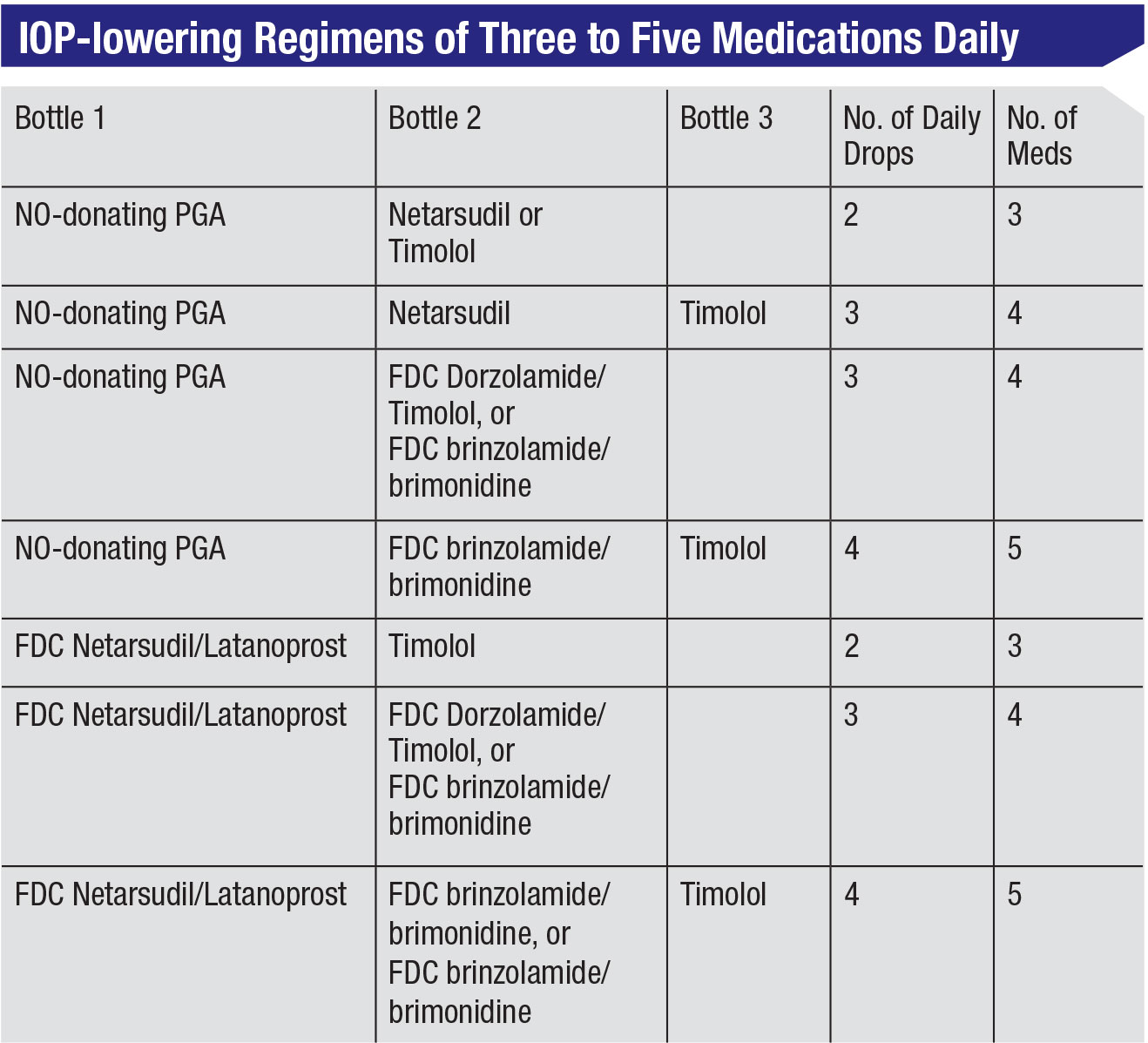

One concern with prescribing multiple drops is how to evaluate the burden a given regimen places on the patient. I propose that rather than counting the medications or number of bottles a patient is using, we should be counting the number of daily eye drop instillations the patient has to make. That, I think, relates best to what a patient can comply with.

Using that perspective, today’s co-drug and fixed-dose combinations can allow us to prescribe more medications without increasing the number of drops, which can make a big difference to many patients. For example, if we prescribe latanoprostene bunod (Vyzulta) with either netarsudil (Rhopressa) or timolol, that would mean two drops a day providing three medications. Both Vyzulta and Rhopressa would be taken in the evening, which for some patients would make the regimen easy to comply with. Typically, timolol would be used in the morning, so combining that with Vyzulta would mean one drop in the morning and one in the evening. Another regimen of two drops a day that would provide three medications is the fixed-dose combination of netarsudil/latanoprost (Rocklatan) which is taken in the evening, with timolol taken in the morning.

Any of these regimens gives the patient three medications with only two drops a day. The same logic could be used to provide four medications with three drops a day, or five medications with four drops a day. (See table, facing page.) In short, the combination drugs give us better options for addressing the issue of patient compliance.

It’s worth asking whether our patients can be expected to reliably administer three or more topical drops per day. In fact, we know from our own practices that many of our patients manage to use three or more drops and are well-controlled. (Admittedly, compliance is difficult to measure; but the surrogate for compliance is our IOP measurement in the office and the stability of visual fields, the optic nerve exam and our nerve fiber layer evaluations.) So a regimen consisting of multiple drops can work for some patients. The issue is knowing when such a regimen isn’t working.

|

Should We Adjust Therapy?

Several things should be considered warning signs that a complex regimen isn’t working out for one of our patients:

• The patient says, “I’m going to do better. You’ll see—my pressure will be better next time.” That’s a red flag that you need to think about alternatives.

• The pressure varies a lot from visit to visit. The reason could involve compliance or the medications not working; either way, you need to move on to other treatment options.

• The patient hasn’t asked for a refill in a year. That tells you that for some reason, the patient isn’t taking—or isn’t buying—the medications.

• The patient doesn’t show up for scheduled appointments. If the patient is poorly compliant with office visits, he or she is probably also poorly compliant with medications.

You should also be on the lookout for a problem if your patient is el-derly. Some elderly patients will have tremors or difficulty squeezing a bottle. In that situation, you should have an honest discussion: Is there someone else in their home, or a caregiver, who can assist with instilling the medications? If there isn’t, then it’s up to you to consider other options such as simplifying the regimen or choosing a laser or surgical option.

My rule of thumb is that if the patient has no complaints and is stable, it’s OK to leave well enough alone. However, even if all seems fine, there are two options you may want to consider. First, it may be possible to simplify the regimen. If you can lessen the number of drops the patient has to use by switching to a combination drop—assuming cost issues are not a problem—then offer that option to the patient.

Second, if the patient has been stable for some time, it might be worth considering conducting a re-verse therapeutic trial. It’s possible that one of the drops your patient is using may no longer be making much of a difference. If that’s the case, you’ll be doing the patient a favor by eliminating it.

For example, if a patient has been well-controlled on three medications for several months or years, you may wonder if one could be removed. If the patient is interested in simplifying the regimen, you can suggest stopping one medication for two to four weeks; then, the patient can return for a checkup to see if all is still well. (If the patient is unhappy because of a side effect, this is also a way to determine if that medication is the cause.)

The challenge with reverse therapeutic trials is that patients often don’t want to make the extra visits to the office. It may be difficult to convince a patient to stop a medication and return for follow-up if he’s not sufficiently bothered by the regimen or side effects. In that case, you should simply stay the course.

No Easy Answers

Is there a “best” regimen? No. The maximum number of medications that’s effective, tolerated and doesn’t undercut compliance varies dramatically. What might be an excellent treatment regimen for one patient could be intolerable for another.

At this point in time we don’t have a clear explanation, but there is certainly an individual response to medical therapy, just as there is to surgery or any other treatment. So for clinicians, finding the best regimen is a process of trial and error. What works best for a given patient will rarely match the result of a clinical study; he or she will be somewhere on the curve. That’s something that we as clinicians must be sensitive to.

Perhaps our biggest current challenge is that we have limited data about the efficacy of the newer drugs when they’re used in combination with other drugs, and whether or not these combinations will help to delay surgery. But—as noted earlier—we do know that in many situations adding even a fourth or fifth drop will provide additional pressure lowering. And we can assume that if we do get a pressure reduction, that will delay any potential surgical interventions for as long as the drugs are effective and tolerated.

As clinicians, it’s our job to make sure the target pressure is achieved, the glaucoma is stable, and the patient is compliant and adherent. Whatever number of drops makes that happen, that’s the right number for that patient. REVIEW

Dr. Serle is Professor Emeritus of Ophthalmology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. She is a consultant to and equity owner in Aerie Pharmaceuticals, a consultant to Allergan and Bausch + Lomb, and receives grant support from Ocular Therapeutix.

1. Jampel HD, Chon BH, Stamper R, et al. Effectiveness of intraocular pressure-lowering medication determined by washout. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014;132:4:390-5.

2. Bro T, Lindén C. The more, the better? The usefulness of brimonidine as the fourth antiglaucoma eye drop. J Glaucoma 2018;27:7:643-646.

3. Spencer SKR, Shulruf B, McPherson ZE, et al. Factors affecting adherence to topical glaucoma therapy. Ophthalmol Glaucoma 2019;2:86-93.

4. Weinreb RN, Bacharach J, Fechtner RD, et al. 24-hour intraocular pressure control with fixed-dose combination brinzolamide 1%/brimonidine 0.2%: A multicenter, randomized trial. Ophthalmology 2019;126:8:1095-1104.

5. Banitt M, Jung H. Ocular surface disease in the glaucoma patient. Int Ophthalmol Clinics 2018;58:3:23-33.

6. de Fendi LI, Oliveira TC, et al. Additive effect of risk factors for trabeculectomy failure in glaucoma patients: A risk-group from a cohort study. J Glaucoma 2016;25:10;e879-883.

7. Ederer F, Gaasterland DE, Sullivan EK; AGIS Investigators. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 1. Study design and methods and baseline characteristics of study patients. Control Clin Trials 1994;15:4:299-325.

8. Gedde SJ, Schiffman JC, Feuer WJ, et al. Treatment outcomes in the Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (TVT) study after five years of follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol 2012;153:5:789-803.

9. Christakis PG, Tsai JC, Zurakowski D, Kalenak JW, et al. The Ahmed Versus Baerveldt study: Design, baseline patient characteristics, and intraoperative complications. Ophthalmology 2011;118:2172-9.

10. Inazaki H, Kobayashi S, Anzai Y, et al. One-year efficacy of adjunctive use of Ripasudil, a rho-kinase inhibitor, in patients with glaucoma inadequately controlled with maximum medical therapy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2017;255:2009-15.

11. Weinreb R, Feldman RM, et al. MIGS: When maximum medical therapy is not enough. Eyenet Supplement 2018.

12. Serle JB, Goldberg JL, Herndon LW, et al. Changing the course of glaucoma: Clinical implications of new therapies for IOP control. Eyenet Supplement 2018.

13. Ustaoglu M, Shiuey E, Sanvicente C, et al. The efficacy and safety profile of Netarsudil 0.02% in glaucoma treatment: Real-world outcomes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci.. 2019; 60(9):2393.

14. Shin DH, McCracken MS, Bendel RE, et al. The additive effect of latanoprost to maximum-tolerated medications with low-dose, high-dose, or no pilocarpine therapy. Ophthalmology 1999;106:386-390.

15. Bayer A, Tas A, Sobaci G, Henderer JD. Efficacy of latanoprost additive therapy on uncontrolled glaucoma. Ophthalmologica 2002;216:443-8.

16. Feldman RM, Bell NP, Nagi KS. Control of intraocular pressure fluctuation: Are combination drugs more effective? Exp Review Ophthalmol 2011;6:2:151-4.

17. Kim JH, Caprioli J. Intraocular pressure fluctuation: Is it important? J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2018;13:170-4.

18. Lamberg H, Kumar N,Reed D, et al. Early clinical experience with latanoprostene bunod. IOVS 2019;60:2395.

19. Kahook MY, Serle JB, Mah FS, et al. Long-term safety and ocular hypotensive efficacy evaluation of netarsudil ophthalmic solution. Am J Ophthalmol 2019;200:130-137.

20. Radell JE, Serle JB. Netarsudil/latanoprost fixed dose combination for the treatment of open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Drugs of Today 2019;55:9:1-12.

21. Weinreb RN, Liebmann JM, Martin KR, et al. Latanoprostene bunod 0.024% in subjects with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension, pooled phase 3 study findings. J Glaucoma 2018;27:1:7-15.