As reimbursement for our services continues to shrink and the number of patients needing our help continues to rise, all of us find ourselves dealing with a crush of patients moving through our offices. This can leave us struggling to maintain the quality of care we provide. Meanwhile, the result can be long waiting times and frustrated and angry patients. For many years, that was the situation in my practice. My patients took a long time to get through their appointments because of the number of patients in the office and bottlenecks that arose in our patient flow. As a result, I had many chronically unhappy patients.

Eventually, I decided to take the bull by the horns and find ways to improve the situation. My determination paid off: In recent years I’ve found several strategies that have increased patient flow through our office, dramatically reducing patient wait times. I’ve also changed the way I interact with frustrated patients, mitigating their anger if wait times do end up being longer than they’d like.

I believe that implementing these strategies has left me with much happier patients and less stress for me and my staff. Here, I’d like to share some of what I’ve learned, so that you can consider implementing some of these changes in your own practice.

Three Patient Flow Boosters

My first goal was to reduce the time our patients spent waiting in the office. I’ve implemented several strategies that have helped to accomplish this. These include:

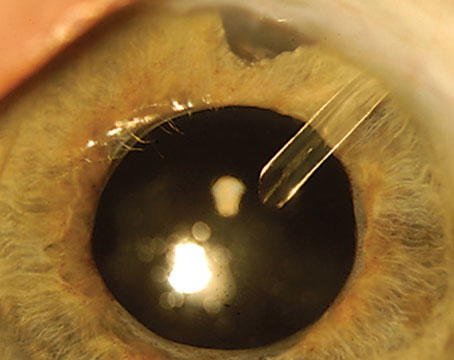

|

| One way to keep patients happier and keep flow moving through the office is to see patients in the order they arrived, rather than at their pre-made appointment time. (It helps if your EHR can list patients in this order, as shown above.) |

• When possible, see patients in the order they arrived. Our electronic health records system allows us to look at our patient schedule in the order that patients checked in (as opposed to when they were scheduled to be seen). (See example to the right) If your system allows you to see that, you can make sure that the patient who got there the earliest is the one you see next. Although this might sound unfair, it ensures that no patient waits a long time simply because they arrived early.

Of course, it doesn’t always make sense to do this; if a patient checked in a lot earlier than their appointment, it’s not really fair to see them first. However, if you do, they walk out very happy. That can give a nice boost to your day. So I try to see patients in “checked in” order.

• Keep the patient in one room while the doctor moves from room to room. A common arrangement in many practices is that the MD sees patients out of one or two rooms, each with a scribe. In addition, there are two or three other rooms in which patients are being worked up by technicians. That means that the work flow is: 1) The patient checks in and goes to the waiting room; 2) the patient is called into a room by a technician and is worked up; 3) the patient goes back to the waiting room; 4) the patient is called into the physician’s room and seen by the physician; and 5) the patient leaves.

To eliminate the repeat visit to the waiting room, we keep the patient in a single room once the visit is underway; instead of the patient moving, the doctor comes in and leaves. So in our system, the patient checks in and goes to the waiting room; then they get called into an exam room by a technician who works them up. Then, instead of sending the patient back to the waiting room, they stay in that room, and the doctor is notified to go to that room to see the patient. In many cases, the technician who’s been working up the patient becomes the scribe during the doctor’s visit. When that’s complete, the patient leaves the practice.

With this system, I’m not just working out of one or two rooms that are “mine,” I’m working out of all of my rooms. I’m hopping from room to room—whichever room the team tells me is where my next patient is.

Note: A key factor that allows this to work is that I cross-train as many of my technicians and scribes as possible to be able to do both tasks. This may be easier said than done, but if you can do that, even with one or two of your team members, it can be really helpful. If cross-training your techs to be scribes isn’t possible, then one of your scribes can follow you from room to room, or you can simply see occasional patients without a scribe.

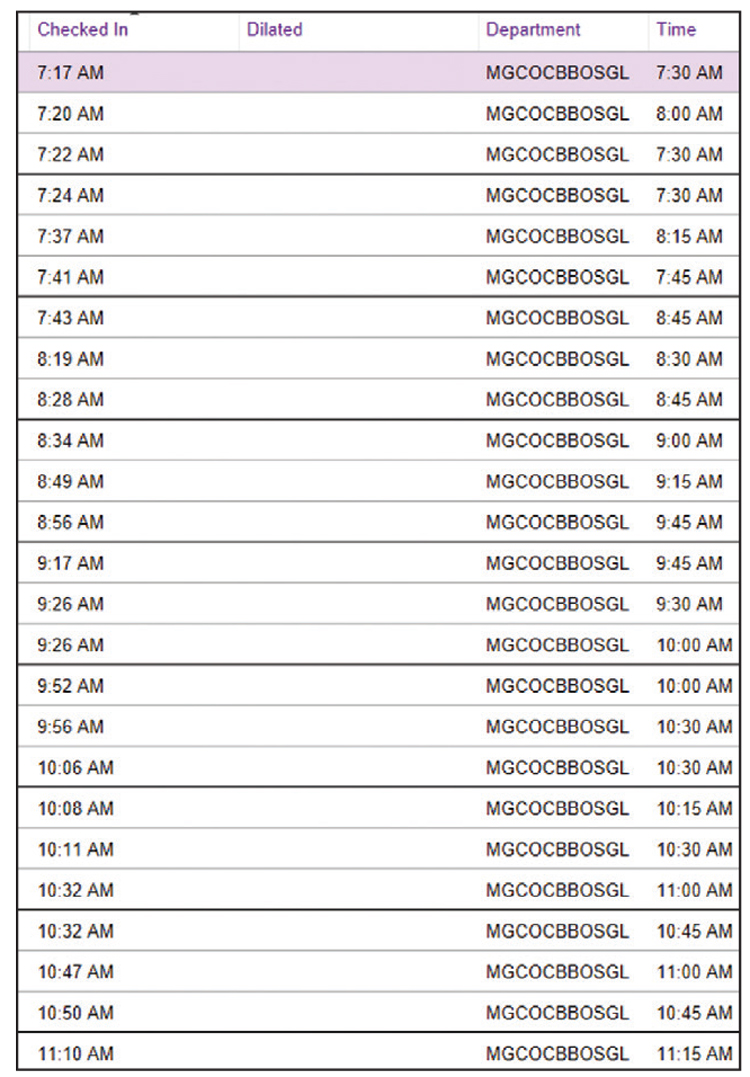

• Use desktop group-chat software to keep all team members apprised of patients’ location and status. Every technician and physician is usually in front of a computer during the workday. Our computers run Microsoft Office, and one of the pieces of software built into that suite is Microsoft Teams, which allows the members of a “team” to communicate between work stations. One of my techs suggested that we could chat with each other using this, making it possible to coordinate our movement between rooms. It turned out to be great for that purpose.

What this means is that every morning when our technicians log onto a computer, we create a “team” that allows us to chat onscreen. When MS Teams is running in the background, if someone in the team sends a message, it shows up in the lower right hand corner of the screen. For example, a note directed to me might say “Room 12 next.” That tells me where to go after I’m done with the current patient. Or, it might show a question a technician has about a patient, or give an instruction from a scribe to one of the techs, such as “get Mr. Johnson into your room next.”

This has turned out to be a very useful tool that we weren’t previously using. It allows us to avoid having to get out of our chair, go to the other room, try to figure out what’s happening and determine who needs to be where. In short, it eliminates a lot of wasted effort.

|

| Some software programs allow anyone in the office to send messages that appear in the lower corner of the screen on computers in other rooms. This is useful if the doctor is moving from room to room to see patients instead of staying in one room with patients being brought to him or her. |

Practical Results

It’s hard to quantify how much this altered workflow has shortened waiting times overall, but it’s clear that patients are getting in and out more quickly and are less upset about extended waiting times. For example, let’s say I have a patient coming in for an eye pressure check and a visual field test; we’re not dilating the patient that day. In the old system, they might show up at 1:00 p.m. for the visual field test; they’d be worked up by the technician and be done by 1:45. Then they’d go back to the waiting room. I might still be seeing my 12:00 or 12:30 appointment, so they wouldn’t get into my room until 2:15 or 2:30. I’d spend about two minutes with them going over their test results, and then they’d leave.

In our new system, they’ll check in at 1:00 for the visual field test and be done with that test by 1:30. Their appointment with me is at 1:30, so they get called in by a technician at 1:30 or 1:40. They get worked up and have their eye pressure checked by the technician, who then calls me in. I might double-check the pressure and then go over the visual field results. So, the patient arrives at 1:00, and has left the practice by 2:00. Essentially, their appointment lasts about 30 minutes less than before, and instead of sitting in the waiting room feeling like they’re being neglected, the extra time before I see them is usually spent talking to the technician in the exam room until I come in.

Admittedly, this system isn’t perfect. In the old system, the technician could grab the next patient to work up after taking the current one back to the waiting room. In my new system, the technician’s room isn't available for the next patient because there’s someone in there waiting for me. But because I’m running between four or five rooms, patients don’t actually wait very long.

Another advantage of our new system is that patients coming in for one simple reason, such as an eye pressure check, can get in and out quickly. In a sense, it gives them a way to “jump the line.” The technicians identify these patients and make sure they get finished up quickly, without disrupting the flow for other patients who need more time and attention.

Another advantage is that in the old system, the patient encounter didn’t end until the patient left my room. Then, I’d have to wait for the scribe to bring in the next patient. With the new system, the patient encounter is ended by me; I get up and move to the next room in which I’m needed. This avoids bottlenecks and wasted time. (Of course, this doesn’t mean that I’m cutting off the patient so that I can leave the room. It just means when I ask “Any other questions?” and they say no, I say, “Go ahead to the front desk and check out, we’ll get you out of here,” and then I leave.)

Smart Telemedicine

Another way we’ve gotten our patient flow under better control and reduced patient cycle time is by implementing telemedicine in a nonstandard way. Patients often have questions that can require fairly extensive answers. For example, we do a lot of cataract surgery. Patients sometimes leave their cataract evaluation visit without having decided on what type of IOL they want. Or, a patient may ask a complex question such as “Am I going blind?” In that situation I may say, “No, if you stick with our plan of taking your medications and following up when I ask you to, the likelihood of you ever being impaired because of glaucoma is miniscule.” That’s enough for some patients, but if it’s not, a longer discussion is called for.

The problem is that having an extensive discussion with a patient during a busy clinic day can be very stressful, and it adds to cycle times, especially if the patient is in a really challenged state and needs time to think, process and ask questions. Ideally, those questions should be answered when it won’t hold up patient flow.

One solution would be to talk to the patient over the phone outside of business hours. However, I’ve always found this unappealing. I don’t want to give up personal time; I don’t want to play “phone tag” with multiple patients; and I never felt comfortable billing for the time involved. For those reasons, I never considered using the phone as a tool to reduce cycle time. I felt that anything I needed to discuss with a patient should be discussed while the patient and I were face-to-face, even if it slowed down our patient throughput.

Today, I’ve found a way to use telemedicine that avoids the downsides I was concerned about. Instead of saying “Let’s talk on the phone after hours today or tomorrow,” I have the patient schedule a call with our receptionist at a specific time during one of our clinic days, in a window set aside expressly for the purpose of having longer conversations with patients.

Offering this option to patients (when needed) is greatly appreciated by the patients. Actually, many patients don’t even take me up on the offer; they realize they’re all set, they don’t need any more time, and they just end the visit. But if I make that offer to four patients a day and they do take me up on it, four 15-minute conversations that would have slowed down patient flow and increased waiting times are now moved to a time slot reserved for that purpose that won’t interfere with patient throughput. That benefits both myself and all of our patients.

If a patient wants to schedule a call, my secretary puts them on my clinic schedule at a later date. In the schedule she notes the name of the patient, time of the appointment, phone number of the patient and the general topic we’ll be talking about. It may be on my schedule at 4:30, but the patient only knows that they’ll get a call from me between 4:00 and 6:00. They’re instructed to be available during that time period, and it’s very rare that they don’t answer.

From my perspective the benefits of this system are multiple: The calls are listed on my clinic schedule, so I never forget one; I almost never have to play phone tag; the calls rarely eat into my personal time; I don’t forget to document the phone call, because it’s a clinic encounter that’ll remain open until I close it by documenting what we talked about; I can often do it during my drive home; and patients really appreciate it. The bottom line is that I don’t make random phone calls to patients anymore.

Making Telemedicine Work

Other things about this telemedicine system worth mentioning include:

• You can use it to reply to patients who call in with questions. I don’t limit this tool to patients who need a lot of time in clinic; I also use this tool for any patient who calls with a question—about anything. For example, I may get a message saying, “I’m having a side effect from this eye drop. What should I do?” It’s a time and energy sink to try calling them back at random, with no idea if they’ll answer, or to ask my secretary to leave a voicemail with my instructions. (I can’t be sure my instructions will reach the patient accurately.) I used to let messages pile up in my in-basket because I was too tired to call patients back, and I never knew what to do if they didn’t answer. This system eliminates all of that; I simply tell my secretary to schedule the patient for a telehealth call in the next couple of weeks.

• Some of these phone conversations may be billable. Whether this is true may depend on factors such as how close the call is to the initiating visit. But to be honest, I don’t care that much about the billing. If I collect a little income, that’s great. But even without that, just based on the time savings, it feels like a win. Furthermore, I get to provide good care for these patients without feeling pressured by the knowledge that other patients are waiting to see me. And my patients really appreciate it.

• You can invoke the pandemic to shorten the in-office conversation. To get a patient to save questions for the phone call, I often invoke the pandemic. I’ll say, “I’ve got all the data I need now, and I want to answer all your questions and help you decide what to do next, but we can’t do that right this minute. As you know, we can’t have patients hanging around the office because of the pandemic. I’d like to get you out of here and not let the waiting room get too full. Let’s schedule a phone call to discuss my recommendations.”

Being able to invoke the pandemic and not apologizing for it is important. I just say, “You remember, Mr. Jones, how long you used to have to wait in our office? Well, we’re not doing that anymore.” Most people are onboard, especially if you offer the fallback option of the phone call. (I don’t think I could be as abrupt with them in the office if I wasn’t able to offer a phone call to give them more of my time.) The majority of patients don’t take me up on the phone call offer, but it helps them understand that the appointment is ending, and I’m available if they need further consultation.

Of course, it’s reasonable to wonder whether this is burdensome for the doctor. I certainly haven’t found it to be; it’s actually been a lifesaver. I recently looked back at a six-month period; out of 4,000 patient encounters, 50 were telemedicine, which isn't even one per day. Generally, I make one to three calls per week.

Managing Upset Patients

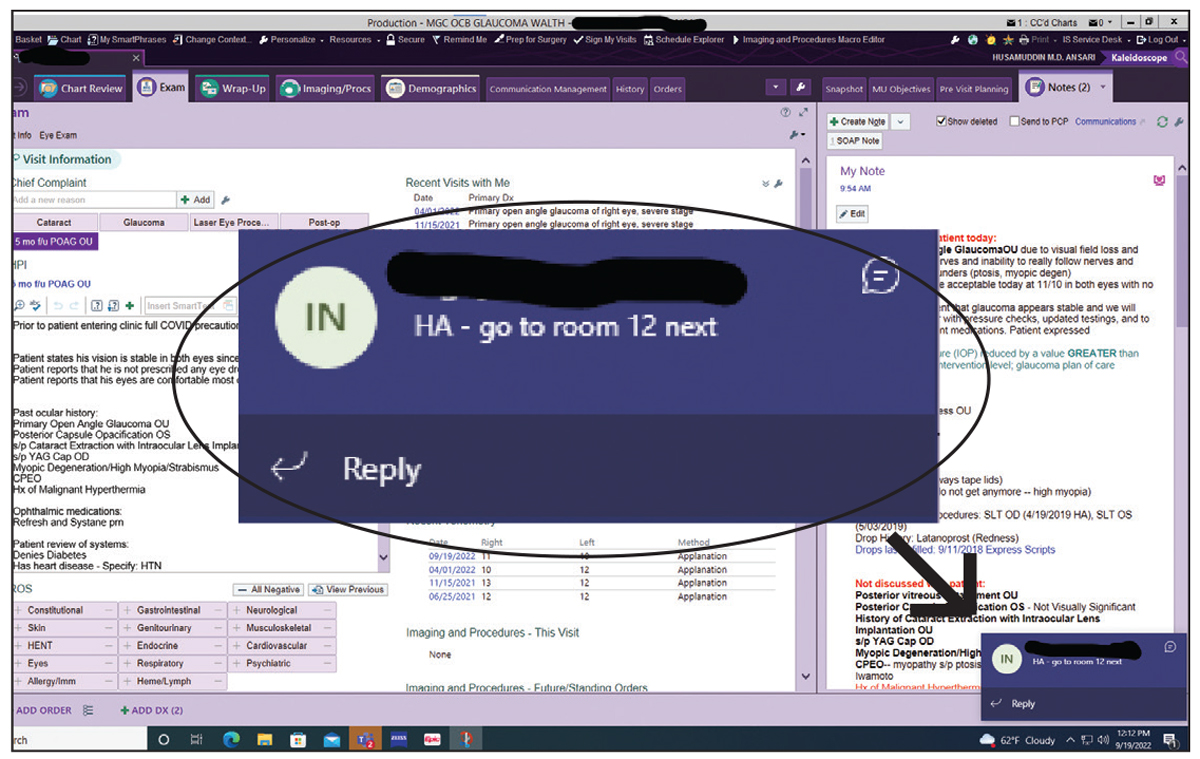

|

| When patients are upset, a key strategy for preventing a wider crisis in the office is to accept the blame and be caring and warm toward the patient—even if that's the last thing you feel like doing. Photo: Getty Images. |

Of course, no matter how much you’re able to improve patient flow in your practice, you’ll inevitably encounter a patient who’s upset about the length of the wait. Most of us are working very hard to provide excellent care and probably feel stressed when patients are backlogged. So it’s tempting to react angrily when a patient expresses unhappiness about a long wait. As you’d expect, doing that will backfire. If you inflame the situation with your own anger, it can get very ugly very quickly.

Using the following strategies will help maintain peace in your clinic and keep an upset patient from becoming even more upset:

• Take the high road. Instead of venting, take a deep breath and suppress your own feelings. Accept the blame for the wait and display an attitude of caring and warmth; tell the patient that you’re working to make the situation better. This may not be what you’re actually thinking, but it will calm the patient down and help keep them from developing a negative opinion of your practice. The idea is to manage the situation in the way that’s most likely to get the result you want, rather than simply venting your true feelings (as good as that might feel).

My practice manager frequently speaks with upset patients; her mantra is “Kill them with kindness.” It really works. Of course, it doesn’t always feel good, because when you’re at your wit’s end you really want to lash out. But again, it gets the result you want.

• Have specific phrases you can use, so you don’t have to improvise. Things you can say in this situation include:

— “I’m sorry for the long wait. We have to do better.” In many cases, this one statement is enough.

— “I know you’ve been waiting a long time. I know it feels like we don’t respect your time. I’m sorry, but I promise I’m here for you 100 percent now.” This defuses the situation and encourages the patient to focus on the fact that the wait is over and you’re giving him or her your full attention.

— “We’re going to keep working on ways to reduce our wait time. But in the future, please do expect to be here for X number of minutes” (whatever number you think is reasonable or realistic). Once you’ve supported the patient by accepting responsibility, you can set more realistic expectations for future visits.

• Explain the need to see unexpected emergency patients. Sometimes it helps to offer an explanation for the long wait. I’ll sometimes go out to the waiting room and say, “I’m so sorry, we’ve had several emergencies today and we’re working very hard to see everyone. We really appreciate your patience.” Usually, the statement that we’ve had several emergencies is true; it’s a frequent occurrence. (Once or twice I’ve said this to mitigate a particularly tough situation when it wasn’t entirely true.)

Of course, you may find that patients who’ve been waiting wonder why seeing emergency patients is even an issue. If I believe that the patient asking about this might be receptive to understanding the situation, I’ll explain that when someone has a crisis involving their eyes, they can’t go to the hospital emergency room; they have to come to us. A hospital ER isn’t equipped to manage an ocular emergency. The reality is, if a patient goes to the ER with an eye problem, they’re most likely going to walk out with an antibiotic drop and a follow-up appointment later that afternoon at the ophthalmologist’s office. So unexpected additions to our schedule are unavoidable—and those patients can’t be postponed. The result is that some of the patients who were previously scheduled will have to wait longer.

Patients sometimes ask why we don’t just reserve some slots for those patients. I explain that unfortunately, the volume of emergency patients is significant. In fact, those slots get booked up as soon as you make them, so when another emergency patient comes in, they need a slot that doesn’t exist. That means that the patients who are scheduled have to wait. (To be honest, we haven’t come up with a way to avoid this problem, so we often have to tell our patients that this is just the way it is. Our office is a de facto “eye emergency room,” every day.)

I do find that explaining this, when appropriate, really does help patients understand what we’re up against. Every eye doctor is in the same position, and we can’t just work around the clock. We do have to go home to our families at some point.

Generally, when I explain this, patients are receptive and understanding.

The Challenge of Change

I realize that some of these changes wouldn’t be easy for every practice to make. Many doctors work in large health systems and don’t have the authority to say that they want to start including telehealth slots in their clinic schedule, or that they want to start cross-training their techs and scribes. On the other hand, I suspect that small practices, where doctors have a lot of autonomy, might be able to implement many of these ideas.

Even I have encountered some bumps in the road in that regard. Most of my practice partners work out of a single exam lane, so I sometimes wonder if my patients think I'm too rushed when they see me hopping back and forth between exam lanes. But if they do, that’s minor. The overall result has been shorter waiting times for my patients and reduced stress for me.

Dr. Singh is a professor of ophthalmology and chief of the Glaucoma Division at Stanford University School of Medicine. Dr. Netland is Vernah Scott Moyston Professor and Chair at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Dr. Ansari is a glaucoma specialist and co-director of the glaucoma fellowship at Ophthalmic Consultants of Boston. He receives research support from Alcon, AbbVie/Allergan, New World Medical and Nicox, and is a consultant for New World Medical.