Every year, surgeons from various subspecialties gather to discuss the latest techniques and technology at the joint meeting of the American College of Eye Surgeons/Society for Excellence in Eyecare. The discussion is always informative and lively, and this year’s meeting was no different. Here is a discussion with three ACES speakers who shared some of the more interesting tips and techniques for refractive and refractive-cataract surgeons.

Optimizing Toric Lenses

Houston biometry guru Jack Holladay, MD, gave an interesting presentation on how to get the most out of toric intraocular lenses.

“Toric IOLs are really increasing dramatically in their usage for the correction of astigmatism,” says Dr. Holladay. “The number comes from Market Scope: Of the premium lenses today, which represent about 14 percent of the lenses used, 7.1 percent of them are toric lenses. That means that their usage is now equal to multifocal lenses, which have been around for a longer time. And it’s deservedly so, because the results are very good if you get the lens lined up and do the calculation properly. However, the commercial calculators currently available on the company websites are incorrect, except for the AMO Toric Calculator, which I developed.” Dr. Holladay says this is so because these calculators use a constant ratio of the cylinder on the cornea to the amount of cylinder that you need on the IOL to neutralize it. The number they use is 1.46 D. “So if the patient has 2 D of corneal astigmatism, the calculators say you need 1.46 x 2 = 2.92 D, and that’s what’s recommended whether you use a 10-D IOL or a 34-D IOL,” says Dr. Holladay. “It is OK for a 22-D IOL, but wrong for a 10-D and 34-D IOL, because the ratio isn’t a constant.”

Dr. Holladay says the ratio can go as low as 1.20 for a 34-D lens to as high as 1.75 for a 10-D lens. “That means you need a lot more toricity to correct 2 D of corneal astigmatism—almost 3.50 D with a 10-D IOL, while you only need about 2.40 D to correct 2 D of astigmatism with a 34-D lens. That’s a 1-D difference in the toricity to correct the same 2 D of corneal astigmatism,” he says. “What the calculation requires is the power for the IOL in the steep meridian and the power in the flat meridian. The difference between those powers is the toricity you need in the IOL. This calculation is done in the Holladay IOL Consultant, and, actually, most of the lens manufacturers recommend that surgeons use our program to do the calculation, because you’ll no longer make errors with IOLs with more unusual spherical equivalent powers.” The calculator also takes into account the axial depth of the IOL, or effective lens position of the IOL—the other important factor when doing this calculation.

Dr. Holladay’s program will also calculate the four locations the surgeon could place the incision to leave zero residual astigmatism.

Track Your Outcomes Online

At the meeting, Greensboro, N.C., surgeon Karl Stonecipher discussed an online outcomes database and tracking service he’s been using called Internet-based Refractive Analysis (Zubisoft, Oberhasli, Switzerland). He says it’s helped enhance his outcomes for both LASIK and cataract surgery.

“You can go online to IBRA and put both your cataract and refractive surgeries in and look at your own data in real time,” says Dr. Stonecipher. “You can analyze it for publication, for doing a check on your outcomes or in an effort to improve your outcomes by analyzing your constants in cataract surgery or your nomograms in refractive surgery.” For example, Dr. Stonecipher says when you look at your nomogram, the IBRA system lets you analyze attempted vs. achieved corrections for a new laser you just started using. You can then switch gears and examine the amount of coupling in your patients’ astigmatism, whether it’s for cataract or refractive procedures. After about 50 cases, IBRA can begin giving useful data, Dr. Stonecipher says, including what your treatment should be for a particular patient based on your own personalized nomogram.

A one-year subscription to IBRA costs about $640. For information, visit

zubisoft.com.

Making Blended Vision Work

Also at this year’s meeting, Fayetteville, Ark., surgeon Jay McDonald provided tips for achieving success with blended vision, another term for monovision. Here, Dr. McDonald explains how the process works.

|

He says that when he finally sees the patient he provides an explanation of how the brain and eye work together to form images, that helps them feel more comfortable with blended vision.“One demonstration that really gets to them is how you can see the tip of your nose when you cover either eye, but when they’re both open you don’t see the nose anymore—because the brain selectively gets rid of it,” Dr. McDonald says. “This helps some of the patients who are worried they can’t consciously handle one eye being corrected differently.” Patients with significant macular degeneration or some obvious issue that will prevent them from using both eyes together aren’t good candidates, however.

Dr. McDonald then moves them on to a series of special tests which aren’t included in their Medicare or insurance, and they’re made to understand that they’ll be paying extra for this testing, and sign an Advanced Beneficiary Notice to that effect.

The testing includes stereopsis tests, foria and tropia measurements (greater than 9 or 10 D of foria will cause the patient to have a tougher time keeping his eyes blended), and a test of their performance with simulated blended vision with +1.5 D of correction, though not with contact lenses. “If they have a bad reaction to the +1.5-D test of their distance and near vision, we have concerns about them being successful,” he says.

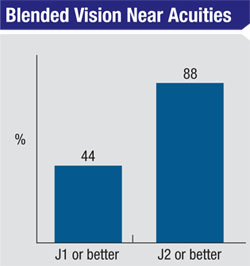

As for the separation in refraction between the eyes, Dr. McDonald likes to use between 1.25 and 1.5 D, along with an aspheric-neutral IOL such as the Bausch + Lomb SofPort AO. “I think that amount is ideal for today’s monovision,” he says. “The original surgeons who performed monovision advocated using a difference of around 2.5 D. However, as you increase the difference between the eyes, you increase defocus, decrease stereopsis and increase the size disparity between objects viewed by each eye. When the difference is 1.25 or 1.5 D, they get stereopsis of 40 to 60 degrees, giving a much better quality of vision, and they tolerate the difference better as well.” He says that with blended vision patients can achieve 20/20 at distance and J1 at a distance of 22 to 24 inches, which encompasses the distance at which they use computers and many devices.

Some of the patients, about 18 percent, will need a small refractive “tune-up” in the office postop, Dr. McDonald says. This extra procedure is also covered by the initial charge.

Dr. McDonald says the other key to success with blended vision is billing appropriately. Dr. McDonald worked with Kevin Corcoran of Corcoran Consulting on the appropriate way to charge patients for the extra testing and postop touch-ups. “The charge comes from the super refraction we do preop, the added global period after the procedure and the potential surgical touch-ups.” (For an in-depth discussion of how to bill for the non-covered services associated with blended vision, see this issue’s Medicare Q&A on p. 28.) REVIEW

Dr. Ferguson is president of ACES and serves on the board of the American Board of Eye Surgery.