More than 36 million people in the United States wear contact lenses. Most will experience no ill effects, but nearly 2 million others have had or will experience one of a host of lens wear complications this year.1 With lenses increasing in popularity, the frequency of ocular complications will undoubtedly continue to climb.

The list of potential contact lens complications is long and varied, ranging from relatively benign protein deposits to potentially sight-threatening microbial keratitis. In this article, we'll discuss several common complications that your lens-wearing patients may experience.

• Protein deposits. These are common and often unavoidable. Fortunately they are arguably one of the most benign contact lens complications. The endogenous proteins and lipids in the tear film often interact and bind with the contact lens polymer. Denatured lysozymes, albumin, gamma globulin and sometimes calcium will build up on the lens surface forming very small raised bumps. These bumps can be easily identified by biomicroscopic examination, but to the naked eye the lens surface may appear greasy or filmy.2 With time, protein deposits can accumulate and cause irritation, blurry vision, itchiness and redness that lead to decreased wear time. In the most severe cases, deposits can become the precursor to an infection, which can lead to serious visual complications. Consider this sign an early warning that these patients should be monitored closely and that the following changes are necessary in their contact lens regimen.

The practitioner can take several steps to reduce protein deposits. Switching to a multipurpose lens solution containing an enzymatic cleaner may help.

Reminding patients about proper lens hygiene and an appropriate wear cycle for their lenses is also important. More frequent lens replacement or daily disposables can also keep protein deposits under control. Consider the material from which your patients' current lenses are constructed. Not all polymers are created equal and some feel that materials such as tetrafilconA and crofilcon have a greater resistance to protein build-up. Remember to take the opportunity to educate your patients on the important steps to keep them on track for a wear schedule they're happy with and an avoidance of potential complications.

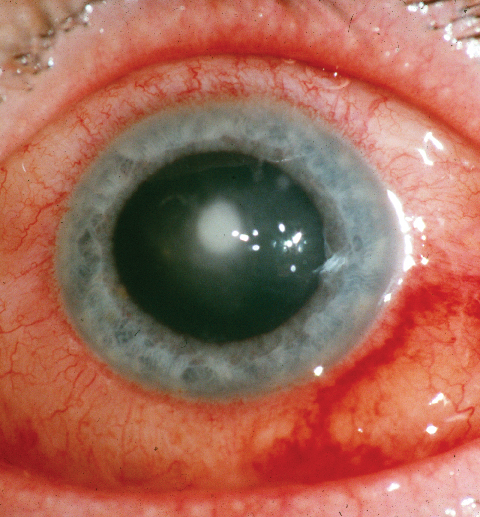

• Corneal neovascularization. This is another relatively common condition associated with soft contact lens wear. Hypoxia from a tight-fitting lens is one of the primary reasons new vessels invade the unvascularized cornea. In some cases, the cause is an old immune infiltrate, which may have lingering vessels even after the original infiltrate is gone. Sensitivity to a cleaning solution may also trigger superior corneal neovascularization. In some cases, excessive lens deposits have caused or contributed to the hypoxic condition, perhaps by altering the Dk value of the lens. Deep stromal vessel growth, though rare, is of greater concern and, if left unchecked, can lead to significant complications.3

When you're faced with this type of corneal neovascularization, keep in mind the differential diagnosis of interstitial keratitis, including syphilis.

Most peripheral neovascularization (micropannus) is considered clinically insignificant, however if vessels intrude beyond about 1.5 mm into the cornea, it's especially important to identify the trigger and remove it. Patients in an extended wear lens schedule should be moved to a daily wear schedule.

Reconsider the lens fit as well as the oxygen transmissibility value. Up to a point, the Dk may be a factor in ensuring the cornea is not deprived of oxygen. As with all ocular abnormalities, monitor neovascularization closely. Vessel growth into the visual axis, although exceptionally rare, can lead to visual impairment via intracorneal hemorrhage, lipid exudation and scaring, all of which potentially compromise the patient's vision.4

• Giant papillary conjunctivitis. GPC is a hypertrophy of the upper tarsal conjunctiva induced by chronic ocular trauma of the lid against ocular prostheses, nylon sutures, exposed scleral buckles and, most commonly, contact lenses. A mechanical mechanism of roughly 6,000 blinks a day combined with an inflammatory response is believed to be the cause of GPC.

The hallmark sign of GPC is papillae >0.3 mm, though smaller papillae (around 0.1 mm) are seen earlier in the stages of the disease. The papillae will be nestled in thickened and hyperemic conjunctival tissue with hyperplastic epithelium growing into the stromal layer. Mucous production, contact lens intolerance, ocular irritation, itching, injection, foreign body sensation and excessive lens movement are all symptomatic of GPC and help confirm the diagnosis.5

Treatment of moderate to severe contact-lens induced GPC is rather intuitive: Remove the causative factor or reduce use of the contact lenses. Also consider exchanging the lens for one with a different edge and polymer modulus. This may help combat the mechanical aspects of GPC. Symptoms usually subside quickly after these adjustments, but it will take longer for the papillae to return to normal. One study has shown that the incidence of GPC is decreased in subjects who wore lenses for three weeks or less.1 Therefore patients should be eased back into contact lens wear, and should follow a daily wear schedule with daily disposables or frequently replaced lenses.1,2 Some practitioners may prescribe mast cell stabilizers or topical steroids to combat the immune response, but this isn't a substitute for reducing lens wear or changing the lens design and polymer.

• Corneal infection. Herpes simplex virus-1 keratitis is the most frequently seen viral condition. Though not usually associated with contact lens wear, HSV keratitis may appear with little warning and, often, apparently no provocation. The HSV-1 lies dormant in roughly 90 percent of the adult population after initial infection via mucocutaneous distribution to the trigeminal nerve. The virus spreads from the infected epithelial cells to the sensory cells, down the nerve axon and eventually to the trigeminal ganglion, where it enters the neuron nucleus and lies dormant.

However, even after decades of dormancy, factors such as emotional or physical stress, overexposure to UV light, hormonal changes and certain medications such as prednisone can trigger the emergence of HSV keratitis. The patient will report redness, tearing, photophobia and blurry vision, but a definitive diagnosis comes from close examination of the corneal vesicles and dendritic ulcers. Though contact lens-related pseudo-dendrites and large corneal abrasion healing patterns can confuse the diagnosis,6 HSV antigen detection tests and viral cultures confirm it. Antiviral therapy will speed resolution of the keratitis and limit stromal damage and scarring. Begin aggressive treatment with trifluridine or vidarabine, and oral acyclovir, accompanied by close observation.

• Microbial keratitis. Bacterial keratitis is arguably the most serious complication of contact lens wear. Fortunately the eye has non-specific defense mechanisms to deter infection. The lids wipe and cleanse the ocular surface; tears flush out debris and pathogens; there is continual sloughing of old epithelial cells being replaced with new healthy cells as well as the immune response system in the tear film, limbus and epithelium.

However, despite the eye's defenses, daily lens wearers and, more frequently, extended-wear lens patients present with microbial keratitis every year. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis have slightly different modes of attack but are the most commonly cultured bacteria.

Patients with infectious keratitis may report pain, photophobia, tearing, purulent discharge and reduced vision shortly after infection. A whitish to yellow infiltrate appears with significant conjunctival injection; surrounding stromal and epithelial edema may follow. Positive culture is the only way to confirm a diagnosis but it's important to begin topical antibiotic therapy early to prevent complications.1

The approved agents for corneal ulcers are Ofloxacin (Ocuflox, Allergan) and the soon-to-be-available Levofloxacin 1.5% (Iquix, Santen). These are dosed every 30 minutes and should be started as soon as possible.

|

Corneal ulcers can form whenever the cornea has been damaged or compromised. Therefore, it shouldn't be surprising that ulcers are seen more commonly in contact lens wearers, especially those who don't practice proper lens hygiene or remove lenses at the first sign of irritation or redness. Whether the ulcer is infectious or sterile will determine the signs, symptoms and appropriate course of action. Infectious ulcers can be very painful, have purulent discharge, possibly iritis, and usually have a break in the overlying epithelium. These ulcers can progress rapidly depending on the bacterial species and condition of the epithelial break. Corneal culture and aggressive, immediate treatment with the appropriate antibiotics will help prevent further complications.

In contrast to infectious ulcers, sterile infiltrates aren't painful and may or may not have an epithelial break. The eye is quadrantically pink, rather than deep red. Small white dots can be seen singularly or in groups in the periphery, and only occasionally in the mid-periphery where they're larger in size and more difficult to differentiate from the signs of infectious ulcers. The two-week natural course of immune infiltrates (Staph. marginal infiltrates) will resolve with a steroid/antibiotic combination within three days. The patient should discontinue lens use and be closely monitored.

Complicating Factors

Three other notable conditions that aren't complications of lens wear, per se, but rather complicate the use of lenses and increase the likelihood of complications are blepharitis, ocular allergies and dry eye.

To minimize problems with blepharitis, the clinician should examine the patient's lids and treat any underlying conditions prior to fitting any contact lenses. This will help prevent discomfort, lens intolerance and possible complications in the future.

Standard treatments for blepharitis include hot compresses and massaging of the lids in an effort to unblock meibomian gland ducts and stimulate secretion. Steroid or antibiotic treatment options are also common and are typically effective. Some systemic antibiotics, such as 50 mg doxycycline b.i.d., have been shown to exhibit lipid-enhancing abilities in addition to their antibiotic mechanisms.7

Ocular allergies such as seasonal and perennial allergic conjunctivitis are also conditions that make it difficult for a patient to wear lenses comfortably due to such allergic complaints as itching, chemosis and lid edema. Prescribing an anti-allergic agent such as Patanol (olopatadine, Alcon) to be used by the patient before lens insertion, and a daily disposable lens may help extend a patient's comfortable lens-wear time.8

Dry eye can also be problematic for lens wearers, forcing them to use rewetting solutions frequently. Visual tasking such as working at a computer monitor, reading or watching TV can be uncomfortable for people suffering from dry eye and contact lens wear may exacerbate these symptoms.

Unfortunately, as long as contact lenses are so widely used, complications are a possibility. Also, with the growing disconnect between lens wearers and the eye-care practitioner (learned intermediary) as a result of mail-order lens companies, the risk to our patients increases and our job becomes more challenging. Making a concerted effort to directly involve our patients in ensuring the health of their eyes is beneficial to everyone.

Dr. Abelson, an associate clinical professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School and senior clinical scientist at Schepens Eye Research Institute, consults in ophthalmic pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Pietrantonio is director of Eye Services at East Boston Neighborhood Health Center and a clinical instructor at the New England College of Optometry.

Mr. Mertz is a research associate at Ophthalmic Research Associates.

1. Stamler JF. The complications of contact lens wear. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 1998;9:4:66-71.

2. Suchecki JK, Donshik P, Ehlers WH Contact lens complications. Ophthalmol Clin North Am 2003;16:3:471-84.

3. Wong AL, Weissman BA, Mondino BJ. Bilateral corneal neovascularization and opacification associated with unmonitored contact lens wear. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;136:5:957-8.

4. Kastl, P. Contact Lenses: The CLAO Guide to Basic Science and Clinical Practice. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. 1995. 1-67

5. Abelson MB. Allergic Diseases of the Eye. New York: W.B. Saunders Company 2001:170-179.

6. Udell IJ, Mannis MJ, Meisler DM, Langston RH. Pseudodendrites in soft contact lens wearers.CLAO J. 1985;11:1:51-3.

7. Shine QE, McCulley JP, Pandya AG. Minocycline effect on meibomian gland lipids in meibomianitis patients. Exp Eye Res 2003;76:4:417.

8. Brodsky M, Berger WE, Butrus S, Epstein AB, Irkec M. Evaluation of comfort using olopatadine hydrochloride 0.1% ophthalmic solution in the treatment of allergic conjunctivitis in contact lens wearers compared to placebo using the conjunctival allergen-challenge model. Eye Contact Lens 2003;29:2:113-6