How would you define sub-Bowman’s keratomileusis? As an anatomical description of thin-flap LASIK? Possibly. As any LASIK procedure a patient might undergo today? Not quite. A term for refractive surgery that’s been around for more than 12 years? You could call it that. The correct answer, however, depends on who you ask.

“Everybody’s correct on this, actually,” declares Dan Durrie, MD, one of the creators of SBK. “In our practice we call it SBK because it represents the latest evolution of LASIK. But many surgeons have their own interpretations. What we like to keep in mind is that this procedure is not your grandmother’s LASIK. If we offered a patient LASIK, the patient might think of a procedure performed on a loved one that created halos or other issues back in the 1990s. With today’s advanced technologies and techniques, every procedure we perform is most definitely not that. We don’t have a lot of those issues.”

No matter what you call this procedure, Dr. Durrie and others recommend that you understand the latest strategies on flap thickness, flap diameter, ablation zones and how to incorporate thin-flap procedures into your refractive surgery offerings. To learn more, read on.

Why SBK?

Dr. Durrie and Houston surgeon Stephen Slade, MD, introduced SBK in 2008.1 “There had been an issue with the early microkeratomes,” he explains. “When we used the techniques available at the time for measuring flaps—with subtraction ultrasound and early OCT—we found a depth variation of 50 µm from patient to patient, even for the same surgeon when the surgeon was using the same microkeratome.”

|

This variation, leaving some pa-tients with flaps that were too thin, explained why some of them developed buttonholes, he notes. “So we solved that problem by going deeper, exceeding the 50-µm range of variation,” he says. “In the cornea, however, that presented problems because it cut more nerves and fibers, creating dry eye and other issues. Plus, we were adding more thickness to the flap, leaving us with less to rely on below the flap for use by the excimer laser to do the procedure.”

Dr. Durrie and his colleagues were able to switch to their thinnest flap ever after the introduction of the femtosecond laser by IntraLase. “We found the variation among flaps was only plus-or-minus 4-µm. With such a magnitude of difference from 50 µm, we realized we didn’t have to cut as deeply because the risk of having too thin of a flap and creating a buttonhole was dramatically reduced by the precision of the femtosecond laser. So that’s when the term sub-Bowman’s keratomileusis, or SBK, came into play, to differentiate a procedure that came to be known by many as thin-flap LASIK.”

Soon, microkeratome manufacturers began making a more consistent blade, allowing surgeons to perform SBK with microkeratomes, if they had the right equipment, Dr. Durrie says. LASIK flaps went from 160 to 180 µm to 110 µm or lower. “The good news is that industry standards kicked up so that everyone started doing thin-flap LASIK surgery. That’s why many surgeons now have a different way of referring to what started out as only SBK.”

Today’s SBK

Dr. Slade, who practices at Slade & Baker Vision in Houston, says he actually came up with the term sub-Bowman’s keratomileusis while working with Dr. Durrie to describe a procedure that he says remains as vital and relevant today as when it was introduced. “We know that SBK reduces postop dry eye,” he says. “It also increases the strength of the cornea. With this procedure, the patient heals more quickly. It’s just less surgery, which is almost always a good thing.”

|

Dr. Slade also agrees that SBK has evolved to encompass broader applications. “The important thing to understand is that what SBK really means is customizing a LASIK flap rather than just doing a standard flap,” says Dr. Slade. “That means customizing the flap to the needs and cornea of the patient. In most cases, it’s an attempt to get a thinner flap. But it’s also typically a flap that’s smaller in diameter and a flap that can even be shaped depending on the pattern of the ablation. The whole idea is to match the flap to the cornea and match it to what you’re doing to the cornea with your laser.”

For example, Dr. Durrie adds, SBK sometimes requires a thicker flap. “If the patient has a corneal scar, that would be an indication for a thicker flap,” he notes. “We might use a depth of 130 µm, instead of 110 µm. We don’t call a thicker flap anything different as far as the patient is concerned. Although we rarely use a thicker flap, we know that we can safely create one—again, because of the precision of the femtosecond laser.”

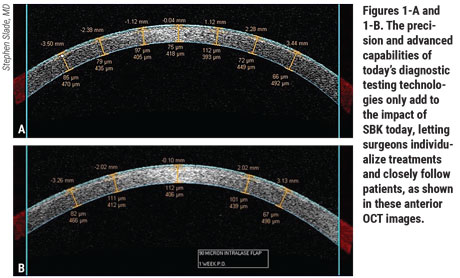

Surgeons point out that the precision and advanced capabilities of today’s diagnostic testing technologies only add to the impact of SBK today, letting surgeons individualize treatments and closely follow patients. Dr. Slade advises against getting trapped by the limitations of a one-size-fits-all LASIK measurement from yesteryear. “Before SBK, corneal flaps were the same for every patient—160 or 180 µm thick and 9 or 9.5 mm wide,” he says. “We realized that this was just way too big and way too deep. The epithelium is 50 µm. So, with 50 µm of stroma, you get a 100-µm flap and you save tissue.

“The size of the flap should also more carefully match the ablation,” he continues. “That varies, depending on your laser and what you set the diameter at. So you need to know your ablation pattern. What is it actually doing? For example, on a WaveLight FS200 laser (Alcon) on a spherical myope—e.g., -6 D—if you set it to 6.5 mm, then 6.5 mm is going to be the entire ablation zone, including the optical zone. There are no shots outside of 6.5 mm or 6.7 mm. So it doesn’t make a lot of sense to do a 9-mm flap because you’ve wasted 1.5 mm on each side. Our routine diameter is 8 mm, but we’ll go down to 7.5 or even 7 mm for a patient like that.”

Taking this approach, he notes, you denervate less cornea, along with speeding up the healing process. “It’s the same thing for PRK. We use smaller epithelium removals to match the ablation. Some lasers have a very wide ablation zone, but a small optical zone. They’ll make shots out to 9 mm because they’re trying to sort of taper and smooth, but the actual refractive change is at 6 mm. Well, then you need to look at the total ablation zone—9 mm in that example—and ask yourself: ‘Do we really need those shots? I mean, laser ablations were all designed for PRK, so they have very broad, gradual transition zones. But you don’t need that for LASIK, or what we call SBK. So the whole point for SBK is to customize the metrics, the dimensions of the flap, for the cornea, and for the ablation pattern that your laser is creating.”

Flap Size

Much of the discussion today about SBK, sometimes called thin-flap LASIK, centers on flap thickness. Most surgeons have settled on a depth of 110 µm for most cases, saying thinner flaps can be difficult to handle and are prone to wrinkling, striae and drying out. But there are notable exceptions.

“We use a 90-µm thickness for nearly all SBK cases we do in our practice,” says Yunuen Bages-Rousselon, MD, who practices in San Pedro Garza García, Nuevo Leon, Mexico. “A flap this thin helps us maintain an appropriate percentage of tissue altered and a greater residual stromal bed. So it’s our standard flap thickness for myopes and hyperopes. In some myopic astigmatism patients, we can go down to 85 or 80 µm. We use the Ziemer z8 femtosecond laser, which allows us to go that low.”

|

Noting that she learned how to perform SBK during fellowship training, Dr. Bages-Rousselon says it’s the only form of flap surgery she has ever done. “I think the benefits of femto-SBK, instead of using a microkeratome, are also important,” she adds. “We achieve uniform flap thickness and diameter, and we have the capacity to alter side-cut angles. We can decrease the risk of epithelial ingrowth when we use the femtosecond laser.”

Dr. Bages-Rousselon exceeds the flap diameter limits observed by most surgeons today with her insistence on a diameter of 9.2 to 9.4 mm for all procedures. “I know most other surgeons would describe the advantage of making the flap smaller, but we make it that large to take advantage of the bigger flap to treat the refraction in these patients. This way, you can fit the treatment and transition zone adequately for myopes and hyperopes. We program ablation zones depending on pupil diameters, and PTA/residual stromal bed calculations.”

Dr. Bages-Rousselon also programs the femtosecond laser to create a flap with an edge at 110 degrees, instead of a 90-degree edge that’s perpendicular to the stromal bed. This allows her to use what she calls an an inverted edge on the flap, with an outward slanted slope that she says discourages the growth of postop epithelium. “When you have that downward slope, it’s like a puzzle fitting together on the periphery, so it’s really hard for the epithelium to grow,” she says. “We continue to get very good outcomes.”

William Culbertson, MD, Higgins Distinguished Professor of Ophthalmology at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami, says a 120-µm flap, is his “sweet spot” for most patients. He uses the IFS (Johnson & Johnson Vision) and WaveLight FS200 (Alcon) femtosecond lasers, but notes that B + L’s Victus platform is also a good choice. “The idea of making a flap thinner without having buttonholes or tears is very valuable, but we don’t think about this procedure as sub-Bowman keratomileusis,” he says. “I was making thinner flaps and doing LASIK before SBK even came out.”

He notes that he will vary his typical 120-µm flap as needed. “For instance, I can go down to 110 µm or 100 µm for a patient who has a high degree of nearsightedness. Why not do it if I can do it and achieve predictable results?”

He continues: “I can tell you that I don’t make intentional 90- or 80-µm flaps anymore, even though I know there are surgeons who do it regularly. If you make an 80-µm flap, the epithelium is now going to be 50 µm,” he points out. “So you’re left with only 30 µm of stroma. For years, we’ve all been trying to figure out how to make a flap thin and still get good results. A depth of 120 µm is where I’ve settled. I think it just gets a little less predictable in many cases when you go thinner than that.”

Dr. Slade also sees little benefit in flaps below 100 µm. “Well, you can do an 80 or 90 µm flap, but I don’t see why,” he says. “I think 100 is plenty. And 80 or 90 µm, sure, I have nothing against them, but I think 100 µm is fine.”

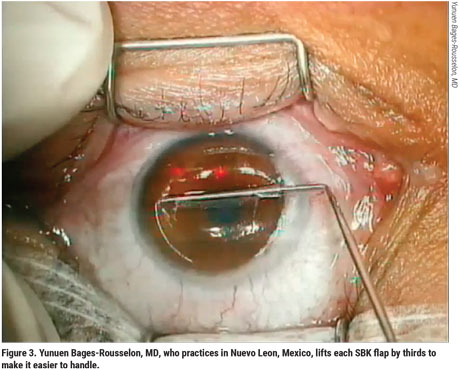

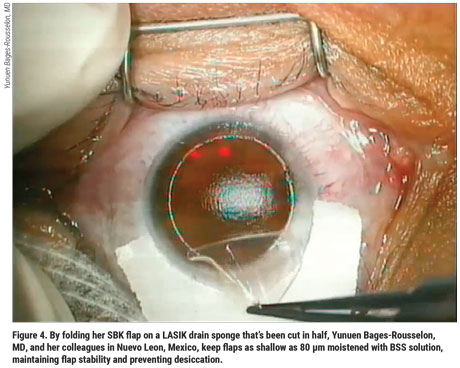

However, Dr. Bages-Rousselon believes the thinner flaps—covering a broader range of corrections with one procedure—are worth her commitment of extra precautions and careful techniques. For example, to minimize the challenges of handling her thin flaps, she dissects the flap by thirds, using a “three-pass-underpass” technique pioneered by Amar Agarwal, MS, FRCS, FRCOphth, and colleagues.2 “After dissecting the flap by thirds, you lift it and fold it back to rest it over a dampened LASIK drain sponge that’s been cut in half,” she explains. “The sponge keeps the flap moistened with BSS solution and also keeps the flap stable and prevents desiccation. This way, we don’t see any striae or have any challenges handling it and laying it back down after ablation. It fits right into place.”

One challenge to be aware of when creating very thin flaps is that you need to maintain hinge thickness, she notes. “This can sometimes be an issue as you center the cut zone,” she says. If the hinge isn’t thick enough, she adds, it risks going up under the cornea. “So we make sure the hinge on the flap is 0.4 to 0.5 mm so that the flap will be quite stable when you lift it.” She also lifts thin flaps very carefully, mindful that they could be damaged by instrumentation.

All Options

Although SBK and thin-flap enthusiasts are fervent believers in their refractive surgery niche, most, if not all, have gravitated to more balanced offerings through the years. Even Dr. Bages-Rousselon will recommend PRK and implantable collamer lenses (but not SMILE) for patients who are not right for SBK, such as patients with inferior or superior corneal asymmetry, as long as they have normal posterior cornea elevations, or patients with corneas that are thinner than 500 µm. Dr. Culbertson is partial to SMILE as an alternative so he can retain the strength of the anterior cornea. He also favors PRK to preserve residual corneal stroma when preserving corneal nerves isn’t as much of a priority. Dr. Slade recommends PRK or ICL. Dr. Durrie says his practice offers SBK as one of eight possible procedures. Beside SBK, the list includes regular LASIK, PRK, ICL, SMILE, clear lens exchange, refractive cataract surgery and corneal cross-linking.

|

“Not one recommendation meets the needs of all patients,” says Dr. Culbertson. “One consideration is if there is vulnerability because of what the patient does for a living or the sport he plays, such as a skydiving or playing football or basketball. After undergoing SMILE, the patient is much less vulnerable to a direct blow that would damage a flap.”

Some surgeons might choose PRK if they don’t favor SMILE as a safer alternative for these active patients, he notes. “So there are options,” adds Dr. Culbertson. “It depends on what the doctor has in his armamentarium. As far as SBK and the LASIK evolution are concerned, I like to think of it as a story about several concerns we’ve had going on through the years. It’s a story of what we needed to do to minimize ectasia. It’s a story about bringing dry eye under control after refractive surgery. And, at the same time, it’s a story of emerging technology that is much more precise but expensive these days. A lot of the terms used today were basically commercial terms to differentiate LASIK with a femtosecond laser from LASIK with a microkeratome. But it keeps evolving.”

Choosing Patients Wisely

In the refractive surgery arena, the one constant is change, surgeons say. The progress of techniques and technologies will continue to drive everything from patient selection to positioning procedures for the success of patients and practices, according to Dr. Durrie.

“Our patient selection process begins by determining if the patient is even a candidate for any kind of refractive surgery,” he says. “We can zero in on which procedure is the best for each individual patient, or even the individual eye of each patient, because we sometimes do a different procedure for the right eye than the left, depending on the status of the corneas. It’s great to have a broad selection of procedures. And we always say, ‘If you don’t do a procedure that’s the best one for a particular patient, refer the patient to a surgeon who does the procedure.’ We want what is ideal for that patient. Pick the right patients for the right technology, and you’ll get great results. This is a simple and effective strategy. Make the selection of the procedure and the technology fit each patient. That’s the way most people look at it nowadays.” REVIEW

Drs. Durrie and Slade are consultants for Johnson & Johnson Vision and Alcon. Dr. Culbertson is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Vision. Dr. Bages-Rousselon reports no relationships with companies related to any of the products mentioned in this article.

1. Durrie DS, Slade SG, Marshall J. Wavefront-guided excimer laser ablation using photorefractive keratectomy and sub-Bowman’s keratomileusis: a contralateral eye study. J Refract Surg 2008;24:1:S77-84.

2. Prakash G, Agarwal A, Kumar DA. The three-pass-underpass technique: A graded flap dissection technique for thin femtosecond sub-Bowman keratomileusis flaps. Eye Contact Lens 2010;36:6:324-9.