Some ophthalmologists are divided over who should administer intravitreal injections to prevent blindness—retinal specialists only or retinal specialists and comprehensive ophthalmologists. “It’s critical to have the ability to confirm the correct diagnosis before injection, and that has been a problem in some instances involving comprehensive ophthalmologists,” says Timothy G. Murray, MD, MBA, president of the American Society of Retina Specialists, which he says officially opposes injections by non-retina specialists. “The diagnosis has been incorrect in these cases. The injection, many of us feel, is the easiest part of the procedure. The hardest part is the diagnosis, comparative monitoring of each injection with OCT and confirming that the patient is clinically sound. To me, it’s very clear that the best practice for intravitreal injections for retinal diseases is treatment by a retina specialist.”

|

However, comprehensive ophthalmologists who inject anti-VEGF agents believe advanced residency training in retina care has sufficiently prepared them to provide anti-VEGF therapy, which they say is needed in remote places where retinal specialists can be hours away from needy patients. Rising demand for treatments could also soon be a concern.

Where do you fit in between the two sides of this debate? It depends on your practice orientation, location, training and interests. Read on to find out how this issue could shape the future of the retinal care your patients need.

More Retina Training

Ophthalmology residency programs have focused more on retina training in recent years, some more intensively than others. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education mandates that each resident perform at least 10 intravitreal injections and 10 panretinal photocoagulation procedures before graduation.1 Michael Patterson, DO, a comprehensive ophthalmologist who performs thousands of intravitreal injections in Crossville and Cookeville, Tennessee, says he trained extensively on retinal care as a resident at the University of South Carolina, performing “hundreds and hundreds” of intravitreal injections under the direction of John “Jack” Wells, MD, a high-profile retina specialist who served as the program director. “We did more retina injections than any other procedure during my residency,” he adds. “There wasn’t even a close second.”

Besides Dr. Wells, retinal specialist Philip J. Rosenfeld, MD, PhD, professor of ophthalmology at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami, also provides residents with heavy doses of training in retina. “Our residents get extensive training in intravitreal retinal injections, the indications for their use, when to retreat, and how to deal with complications,” he says. “I’m totally comfortable with any of them giving intravitreal injections after they complete their residency. If an ophthalmologist is adequately trained and has appropriate support from a retina specialist if complications arise, then intravitreal injections don’t have to be given by a retinal specialist. But injections have to be given by a trained ophthalmologist who really understands the disease being treated; when it’s necessary to inject; how to administer the injection; and what to look for after the injection regarding the potential complications.”

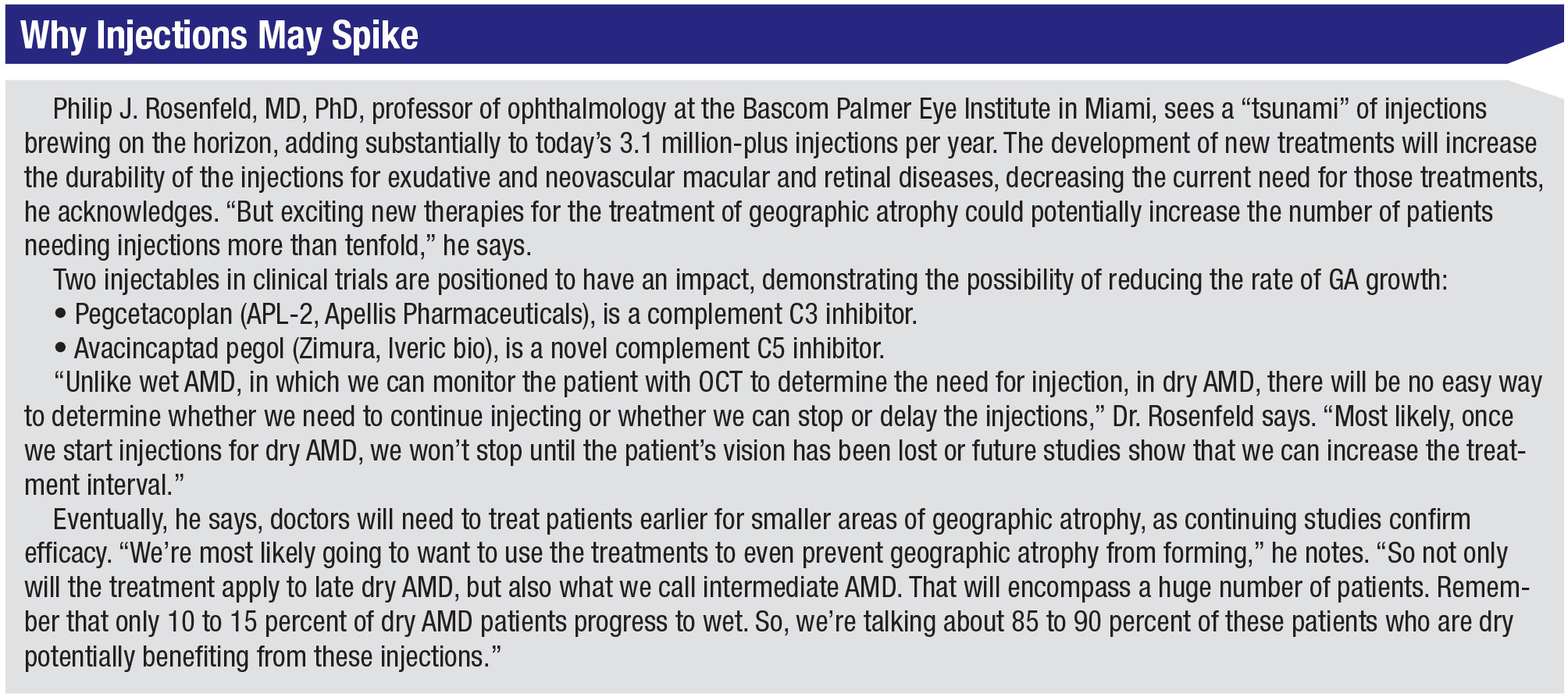

Dr. Rosenfeld expects more comprehensive ophthalmologists coming out of training will need to provide this care when intravitreal therapy for dry AMD is mainstreamed and the number of injections skyrockets in the years ahead. “We’ll need to meet the demand,” he says. (See “Why Injections May Spike,” below.)

|

Injection Challenges

Dr. Murray of ASRS acknowledges that more ophthalmology residents are now learning to perform intravitreal injections. “But training ophthalmology residents to provide these procedures doesn’t make them capable of properly managing intravitreal injections and the variety of complex retinal diseases encountered in clinical practice,” he says. “The challenges we’ve been trained to deal with include all retinal diseases, plus unexpected and potentially serious complications.”

Carl C. Awh, MD, the president-elect of ASRS, agrees that a retina specialist should treat these patients. “These drugs work so well that you don’t necessarily have to be an expert to get a very good result for most patients,” he admits. “Giving the injection is technically within the skill set of any ophthalmic surgeon. But a lot of cases aren’t typical. Even in clinical trials, some well-meaning doctors haven’t necessarily recognized when their patients weren’t doing as well as they could’ve been doing. So for those of us who started in practice prior to this age of miraculous anti-VEGF drugs, when we watched our patients almost inexorably lose their central vision over the years, anything that prevents this outcome can seem like a success. But we’ve learned that optimal treatment with anti-VEGF therapy can mean the difference between vision that’s good enough to drive a car and just functional central vision. No matter who’s treating them, very few patients will become legally blind. But there’s a huge difference between having 20/60 vision and 20/25 vision.

“Because of our extensive training and exclusive focus on the retina, it would be very hard for any general ophthalmologist to show in any objective way that he or she would be better than a retinal specialist at managing a patient with a chronic, potentially blinding retinal condition,” continues Dr. Awh, who practices at Tennessee Retina, the largest retina group in central Tennessee. “I don’t think there are many areas in this country where care by a retina specialist is not available. However, above all, it’s essential that patients who need treatment have access to treatment. So if there were a scenario in which the only way for the patient to get treatment was through a comprehensive ophthalmologist, and not a fellowship-trained retinal specialist, I would be all in favor of that.”

Caring for the Underserved

|

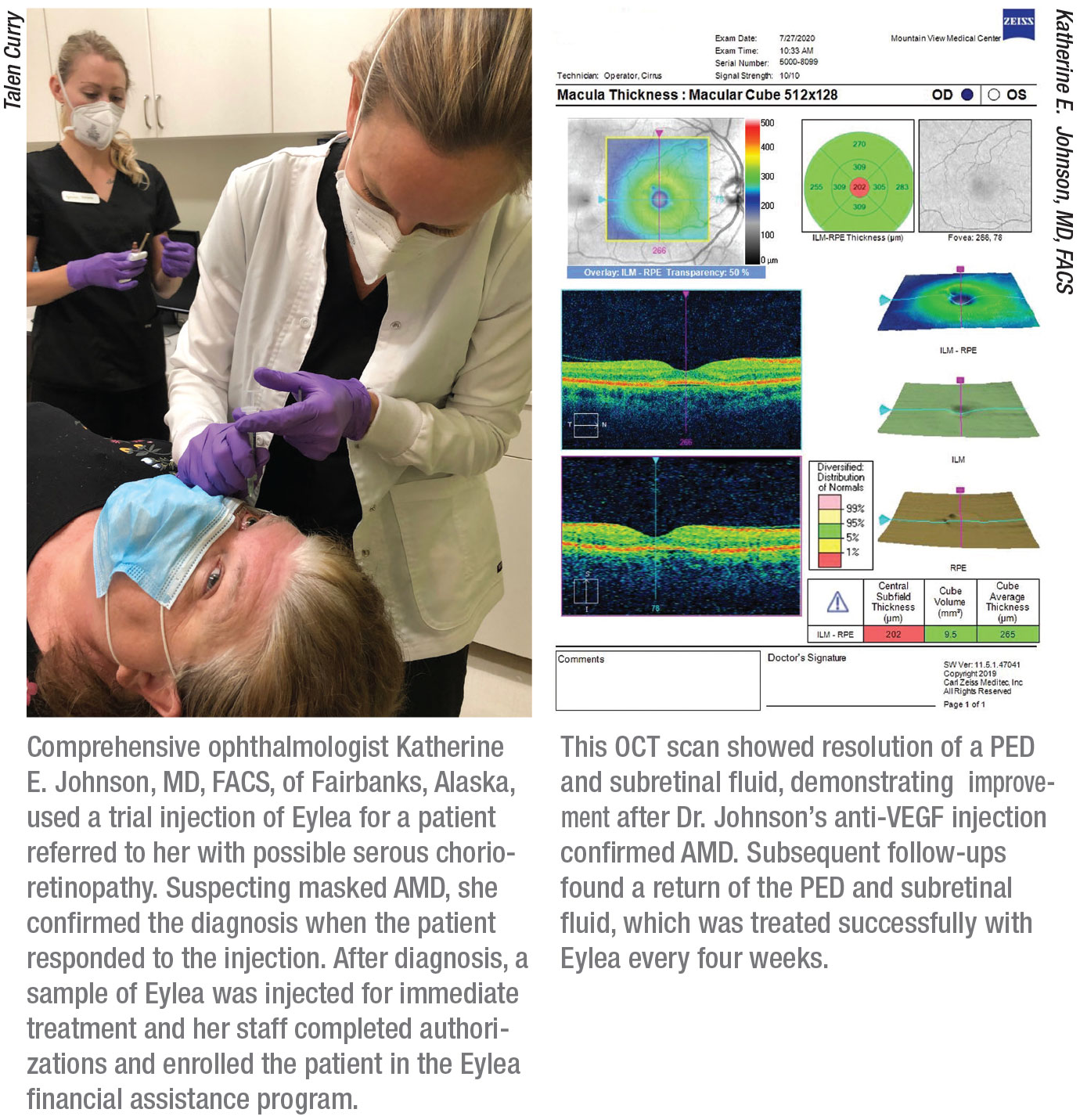

Katherine E. Johnson, MD, FACS, who trained under Dr. Rosenfeld at Bascom Palmer, is just the type of comprehensive ophthalmologist Dr. Awh has in mind. Dr. Johnson, who has cared for patients in Mexico and Nepal and has founded two international programs aimed at preventing blindness, owns a private practice that serves a population of 100,000 residents in Fairbanks, Alaska, and surrounding areas. “When I showed up here 12 years ago, nobody was doing intravitreal injections,” she says. “Patients were sent to Anchorage for injections, requiring a six-hour drive or one-hour flight. The impact of those trips financially—plus the burden the trips put on the schedules of patients and their families—was very significant. It makes you wonder how many times patients just went without treatment instead of taking those long journeys every month. If the ‘standard of care’ is making patients and their escorts travel over six hours each way for a monthly injection, then I would say that’s a terrible standard of care. It’s hard for me to believe that doctors would want this for patients when the alternative I offer is available.”

Dr. Johnson agrees that a doctor injecting anti-VEGF drugs should be capable of managing the complications of any procedure he or she performs. “Of course, the most concerning complication would be endophthalmitis, and I’m very capable of doing a vitreous tap and antibiotic injection, if needed,” she says. “In fact, when I arrived in Fairbanks 12 years ago, I designed the protocol for this procedure at my local hospital, based on the Bascom Palmer protocols. Luckily, the need is rare, but the ability to perform this now exists locally.”

Dr. Johnson administers 10 to 12 intravitreal injections per day; medical retina constitutes about half of her practice. She notes that the only procedure she wouldn’t perform is a vitrectomy. “But statistically, the risk of endophthalmitis is exceptionally rare and a vitreous tap-and-inject can postpone a needed vitrectomy to allow for travel time to Anchorage,” she says. “In fact, the last infection I treated this way was a postoperative infection from retinal surgery performed elsewhere, demonstrating the importance of having this skill set in remote areas.”

In the event of a complication, she adds, “I’m able to do an anterior parenthesis without any hesitation.” Because Dr. Johnson is a comprehensive ophthalmologist, she points out that she can monitor both the patient’s glaucoma and AMD. “Because I have a unique understanding of the status of a patient’s glaucoma progression, I can factor glaucoma-related information into my decision-making,” she says. “We have patients who have advanced-stage glaucoma. And with macular degeneration, we need to decide if we should still chase the macular degeneration in eyes that are 20/800. We might hold off on an injection if a patient’s glaucoma is more threatening to the patient’s vision than the macular degeneration.”

Dr. Johnson also sends out images to five or six retinal specialists for second opinions when necessary.

Similarly, Dr. Patterson, the comprehensive ophthalmologist in Tennessee, says anti-VEGF treatments add another dimension to his relationship with local retinal specialists. “The retinal specialists help us and we help them,” says Dr. Patterson. “The retinal specialists may experience a complication from an IOP rise or acute glaucoma from putting in a dexamethasone implant [Ozurdex, Allergan]. They can’t fix this because they don’t do tubes, and I can use tubes to help. They aren’t equipped with an SLT device, which I can use to help with their ocular hypertension patients. Meanwhile, if we do cataract surgery that results in a dropped nucleus and endophthalmitis, they can fix that for me. I’m not worried because I love our retinal specialists. We do a ton of work together.”

Deep Misgivings

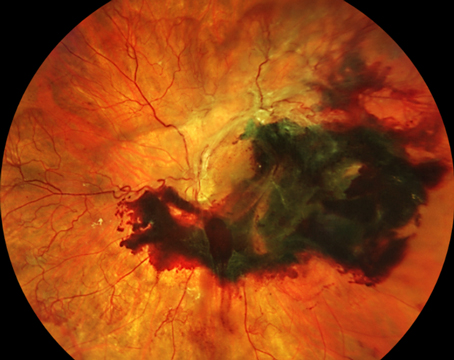

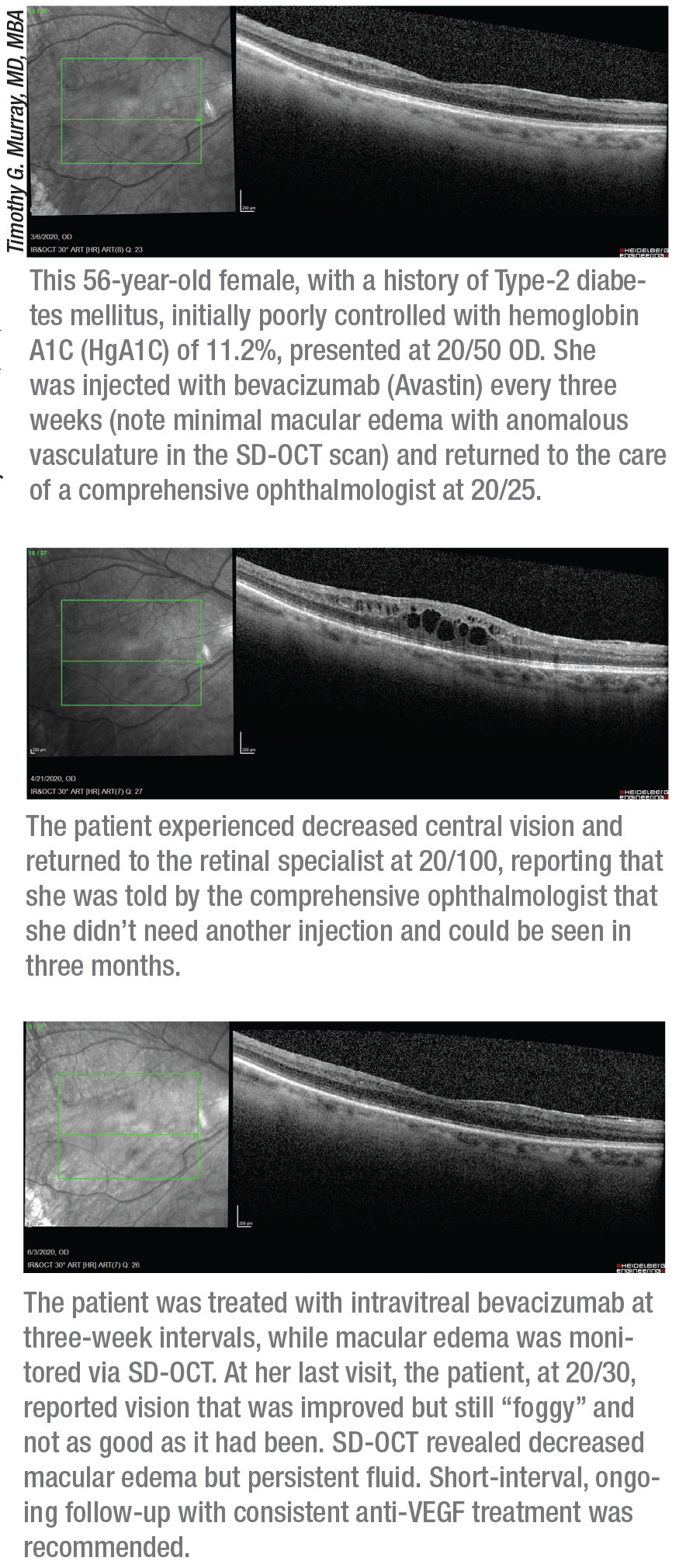

Despite these positive experiences, Dr. Murray, speaking on behalf of many of his colleagues in retinal care, firmly believes that patients face unnecessary risks when receiving anti-VEGF injections from a non-retinal specialist. He notes that no case of neovascular AMD, retinal vein occlusion or diabetic retinopathy is the same.

“Deciding on what to treat and when to treat and whether to discontinue treatment can have major implications for your patient’s vision,” he says. “Determining when an eye has transitioned from dry to wet AMD can be daunting. Some eyes may have indolent, occult neovascular AMD that remains stable for a prolonged period without intervention. Previous experience and close monitoring of these eyes is imperative for deciding when treatment is indicated.”

Other important challenges to be mindful of include:

• determining if a PED is associated with choroidal neovascularization and requires treatment;

• responding to a retinal pigment epithelial detachment;

• having to determine when an eye with neovascular AMD has type 1, 2 or 4 CNV, retinal angiomatous proliferation and/or polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Each of these subcategories of wet AMD may respond differently to anti-VEGF agents. Some are better treated with a thermal laser or photodynamic therapy, rather than with anti-VEGF agents.

• determining if fibrosis in a lesion indicates stability; and

• responding to recurrent CNV.

“You need to be prepared for the unexpected,” Dr. Murray says. Macular edema from retinal vascular occlusion or diabetic retinopathy may not compromise vision in some cases or, when it does, may not respond well to anti-VEGF agents, he points out. “A strong background in retina care is required to determine when a combination of intravitreal steroids and continuing anti-VEGF therapy is needed,” he says. Another example: Lack of capillary perfusion can be found in retinal vascular occlusions and diabetic retinopathy, affecting long-term treatment. “The physician needs to know when to use the laser. Laser treatment and anti-VEGF may be best for some patients. Knowing when and how to incorporate PRP into the long-term care of proliferative retinopathy is critical.”

|

Too Many Challenges?

Is it impossible to meet all of these challenges in a comprehensive ophthalmology practice? Dr. Johnson says the answer is no. “I do PRPs and retinal tear demarcations all the time,” she says, noting that she combs the literature and attends Hawaiian Eye and the Retina Subspecialty Day at the American Academy of Ophthalmology meeting to keep up to date. “I don’t laser the entire retina at one time because I have the luxury of bringing patients back multiple times to decrease the inflammatory response to the laser, just as I was trained to do at Bascom Palmer. I certainly have enough volume to maintain a high-level skill set in medical retina. There are several other fields that I don’t practice in because of limited volume to maintain a level of excellence, such as pediatrics or corneal-transplant. I’m only going to practice exceptional quality medicine.”

She recalls when a stray vitreous strand kept one of her injection sites open for three days. Because she uses a post-injection Betadine drop as a “Seidel test,” she avoided a disastrous outcome by bringing the patient back several times over three days and treating the area with antibiotics. Another time, a patient visited with what appeared to be central serous chorioretinopathy. She suspected masked wet AMD and confirmed the diagnosis when the patient responded to a trial injection of Eylea. (See page 49.)

“What I do takes longer, but I don’t need to meet the demands of a 60-patient injection clinic,” she says. “I dedicate time to a quality injection. I perform all needed risk mitigation—and more, in some cases—and I exceed standards of clinical care.”

Continuing to Evolve

Ronald Frenkel, MD, a retinal and glaucoma specialist in Stuart, Florida, believes changes in anti-VEGF therapy will continue to evolve, especially as efforts to address care disparities and disease burden progress. “This will be an individualized issue,” he says. “The comprehensive ophthalmologist will need the right training in retina. Rural areas may have slightly—or vastly different—needs and availability of retinal doctors, so the patient might be treated by a comprehensive ophthalmologist in those areas more so than in other areas, where retinal specialists may be available. I’m hesitant to draw firm lines in the sand.” REVIEW

1. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Ophthalmology. https://www.acgme.org/Specialties/Documents-and-Resources/pfcatid/13/Ophthalmology. Accessed 8.12.20.