As you know, ensuring patient happiness after cataract surgery can be difficult at times, requiring you to explore the use of lens exchanges, piggyback lenses, refractive surgery with lasers, capsulotomies, management of ocular disease and other interventions to put a smile on the faces of frowning patients.

“Satisfying unhappy patients is always a priority, especially when it comes to premium IOLs, because patient expectations are so much higher than they otherwise would be,” says Brandon Ayres, MD, assistant surgeon at Wills Eye Hospital and an instructor at Jefferson Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

“These patients are paying out of pocket, and they expect to pay for performance,” he continues. “Many times, you get that performance but sometimes you don’t. So at times it can be sort of a tricky pathway to follow. With any cataract surgery, we have to be prepared to use a number of options—or combination of options—to achieve our goals.”

Through the years, surgeons have crafted personal protocols for trouble-shooting and meeting the challenges of these cases. In this report, leading surgeons share insights on their approaches.

|

Your Start Time

Although effective responses to unwanted outcomes are critical to your surgical plan, planning for the worst by doing your best before surgery is equally important, according to Mark Kontos, MD, senior partner at Empire Eye Physicians, which has offices in eastern Washington and northern Idaho.

“The best way to deal with postop issues is to not have to deal with them because you’ve taken the time to understand what patients want before surgery,” he says. “Understanding their expectations can significantly increase the likelihood of achieving happiness.”

Below are key questions that Dr. Kontos uses to guide his preop conversations with patients:

• Do you want to be free of glasses?

• Do you care if you’ll still need glasses after surgery?

• Do you want clear distance vision without the need for glasses?

• Do you want to read without glasses but don’t care about wearing glasses to see clearly at a distance?

A reality check is also critical. “Are the patients’ expectations based only on what they’ve been told by family and friends who’ve had cataract surgery?” asks Dr. Kontos. “Do their descriptions of the surgery and their anticipated results match the procedures you’re planning plus their best potential outcomes? The more you probe, the better you’ll be able to educate them on what’s possible.

“For example, you might not be able to offer the laser cataract surgery that your patient’s friend underwent. Or you might need to tell a patient with macular degeneration who wants a presbyopia-correcting lens that this won’t be a good combination.”

On the technical side, Dr. Ayres tries to avoid what he calls “a patient selection error.”

He emphasizes the essential need for you to use proper communication with the patient, keeping in mind that today’s ever-advancing IOL technology requires increased precision in offering patients the right refractive solution.

“Near vision expectations vary with these new IOLs,” he notes. “We need to consider the differences among expanded-depth-of-field, multifocal and accommodating IOLs. A careful slit lamp exam as well as a good understanding of the psychology of the patient are critical.”

|

Two-step Protocol

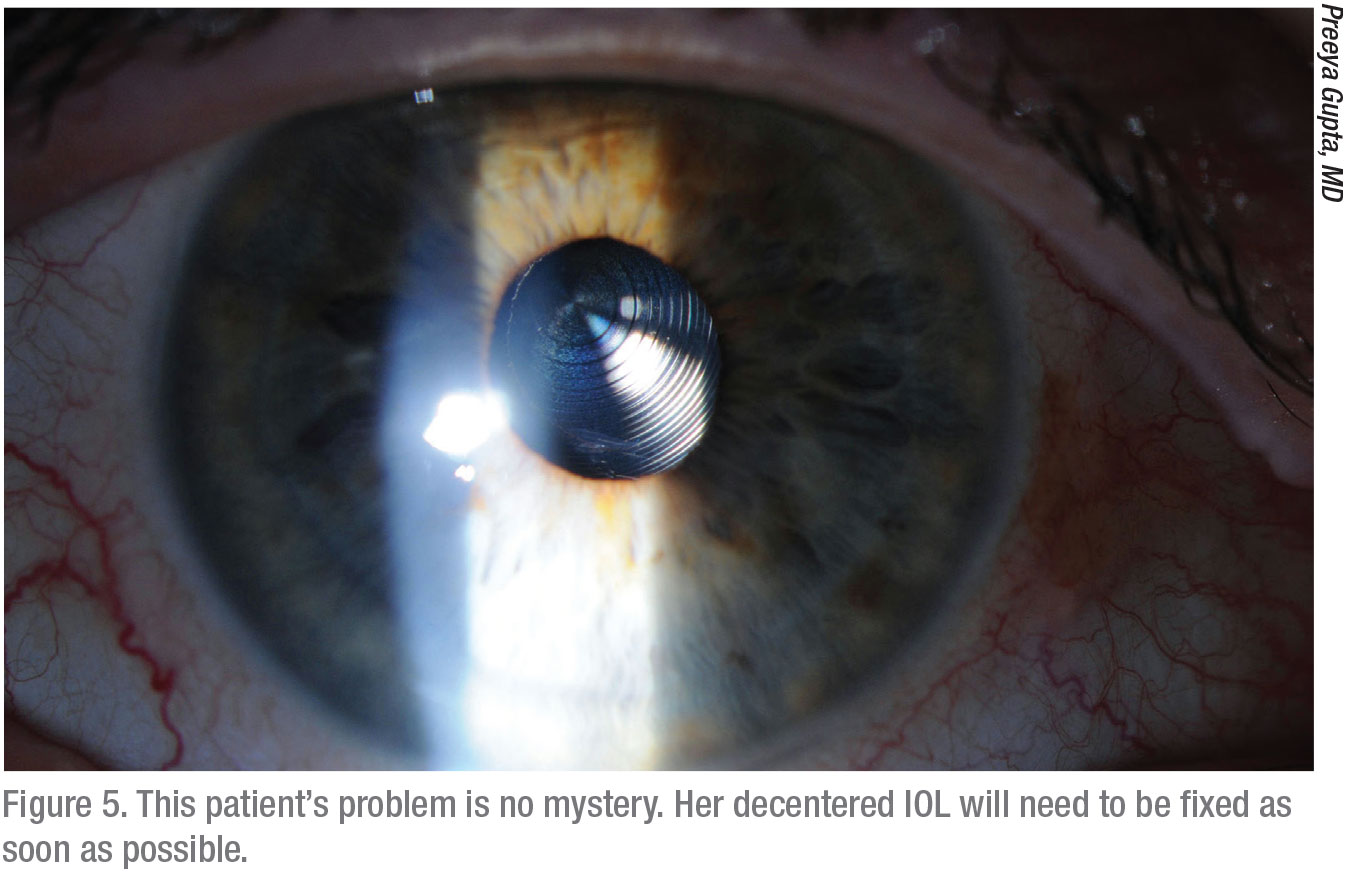

Despite the clearest preop counseling you can provide, some patients will always be unhappy after the procedure, points out Preeya K. Gupta, MD, a corneal specialist at the Duke Eye Center. Dr. Gupta, another firm believer in deep listening as a first step in partnering with preop patients, puts dissatisfied patients’ postop concerns in two categories:

1. early postop period, within the first month; and

2. beyond the early postop period.

“I spend a lot of time with unhappy patients to identify what’s bothering them after surgery,” she says. “Is it sensation? Pain? Irritation? Blurred vision? And so forth. I think that most clinicians who effectively address postop unhappiness are comfortable hearing complaints during the first few weeks after surgery. The most common issues are blurry vision, irritation or some other form of discomfort. These symptoms account for about 90 percent of what patients complain about the most early on.”

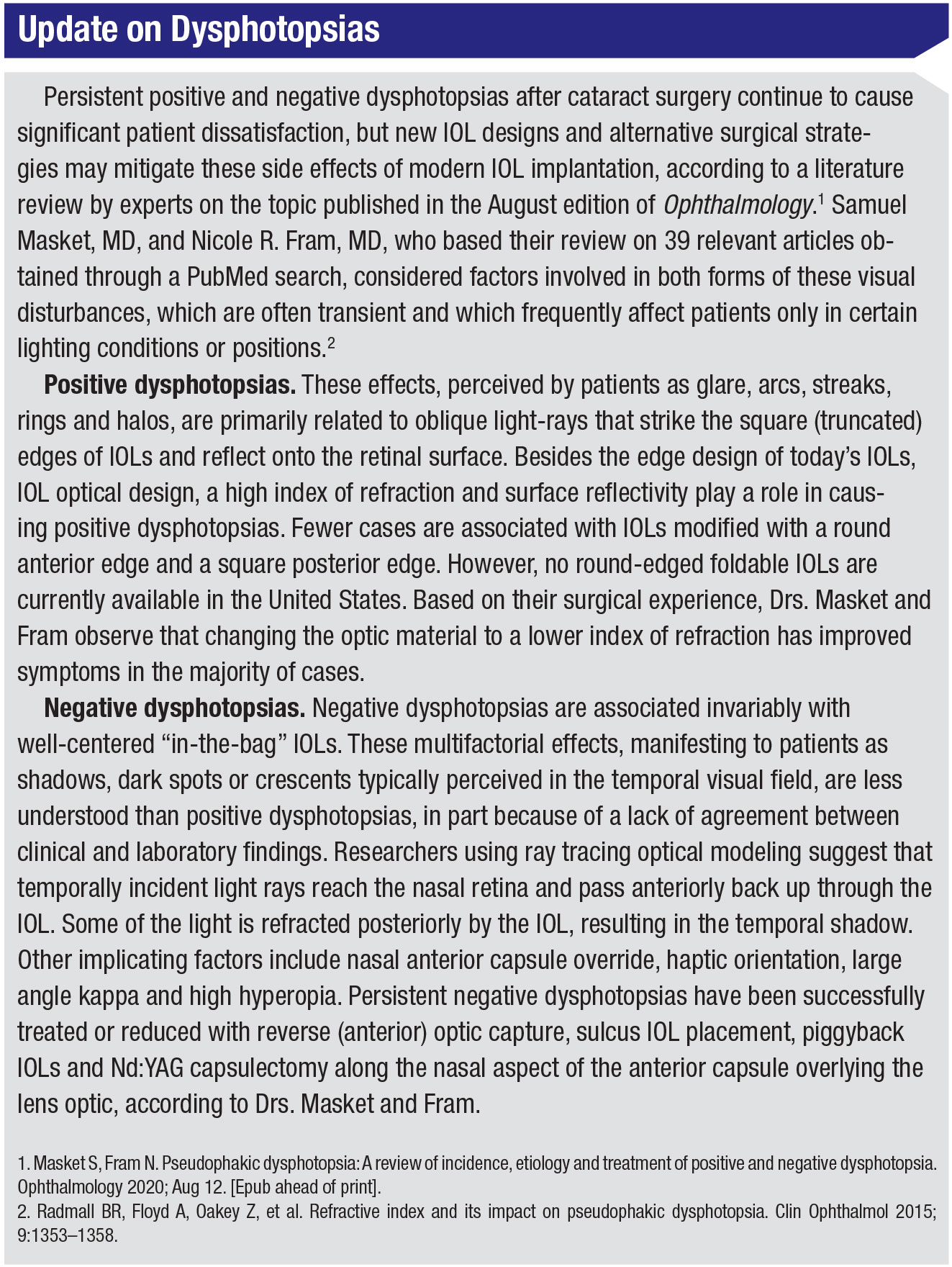

The rest of the issues belong in what Dr. Gupta calls the “the large other” category—those sometimes-challenging, sometimes-simple, usually-infrequent and typically-not-serious postop issues. “Some patients might be affected by negative dysphotopsias, which can develop early on after the implantation of any type of intraocular lens,” says Dr. Gupta. (See “Update on Dysphotopsias” on below.) “Some patients may perceive halos or glare—far more commonly after multifocal IOLs have been implanted.”

Dr. Gupta’s practice provides a handout that explains these symptoms, describing them as typically short-lived and experienced by many other postop patients. “The handout also offers trouble-shooting advice,” explains Dr. Gupta. “This resource saves a lot of phone calls to the office. It goes a long way in terms of helping to set realistic expectations.”

Typically, after 30 days, pain and inflammation have subsided, she notes, adding that the structural integrity of the eye is fairly consistent and stable in 99 percent of postop patients at this point. “Many problems that persist relate to ocular surface disease, which is very common among the limited number of patients who are still having trouble,” she says. “Pre-existing dry eye is typically the most difficult postop challenge we face. Many cataract patients are older, obviously, and many of them have ocular surface disease that hasn’t been diagnosed preoperatively. They may have been asymptomatic and become symptomatic because of surgery. That’s one large area of potential concern. And certainly this can cause blurred vision.”

|

From All Directions

Dr. Ayres says he sees a disproportionate number of unhappy post-cataract patients. “I’m often sent patients who, for whatever reason, are either not seeing well or aren’t happy with their vision, whether it’s loss of contrast or unwanted images, such as halos, negative dysphotopsias, etc. I try my hardest not to create my own unhappy patients. But of course if you’re putting lenses in, you’re going to have a patient at some point who isn’t happy with a lens.”

His goal is to problem-solve thoroughly and do lens exchanges only when it’s absolutely necessary. “In any study, when you read of unhappy patients, especially those with premium IOLs, residual refractive errors and ocular surface disease are two of the leading causes,”1 he says. “If you can address these issues, you can make unhappy patients happy. If you’re off-target with their IOLs—say a toric is misaligned, you can go back and realign the toric. Or it may require you to rely on the manifest refraction to shed light on the problem. That’s where the ‘magic eraser’ of the excimer laser comes in. You can do a refractive procedure, whether it’s LASIK or PRK, and meet patient expectations.”

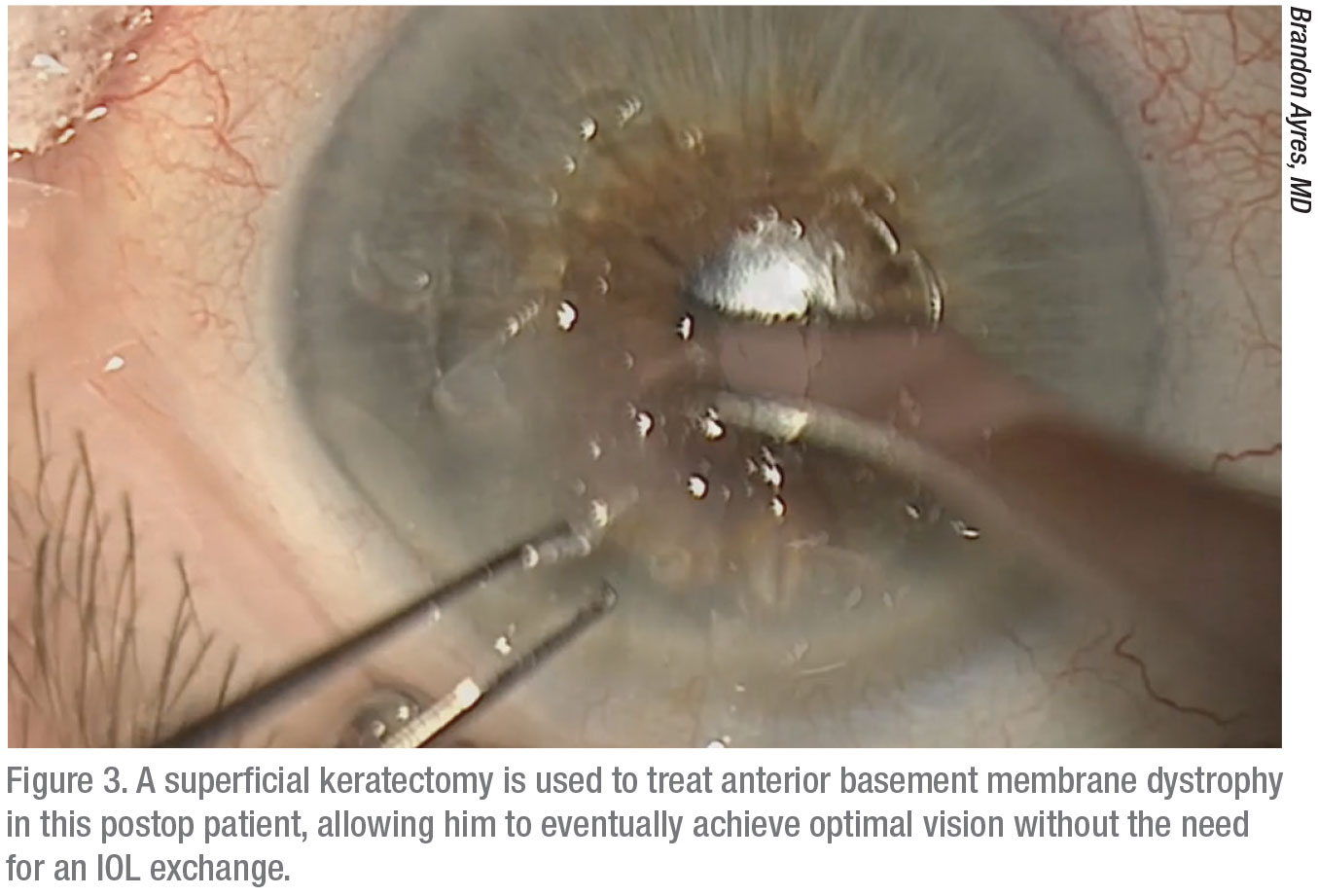

Frequently, Dr. Ayres discovers an opportunity on the corneal surface to turn a case around. “When I look closely, I might see a little anterior membrane dystrophy along with a bit of undiagnosed dry eye,” he says. “I’ll usually put these patients on a prescription anti-inflammatory, such as cyclosporine (Restasis) or lifitegrast (Xiidra). He also relies on preservative-free tears, topical steroids, punctal occlusion and autologous serum, as needed, and he aggressively treats co-existing conditions, such as dry eye and blepharitis. “With enough time and treatment, you can get these patients to be at least satisfied enough with their vision to opt to keep the lens and not undergo a lens exchange,” he says.

How long should you wait for a positive turn of events? It depends on the source of the underlying problem, according to Dr. Ayres. “If we see a nodule or anterior basement membrane dystrophy that requires a superficial keratectomy to remove, an effective solution can sometimes require six to eight weeks,” he says. “Those are actually the easier cases, because you have a very defined problem and solution.”

More traditional dry-eye disease can be more difficult. “The treatment of the ocular surface is quite challenging,” says Dr. Ayres. “This disease is very easy to diagnose and not so easy to treat—and to treat well. So those patients might take two to four months before they turn around. And sometimes, treatment needs to include an office procedure, such as a LipiFlow or some other kind of meibomian gland/blepharitis therapy.”

Planning for the Unexpected

Of course, refractive surprises always remain a potential problem in the cataract surgery arena. At Empire Eye Physicians, Dr. Kontos responds calmly to surprises with a consistent approach. “If a patient is hyperopic to a significant and bothersome degree, our general feeling is to go ahead and do a lens exchange,” he says. “If the patient requires a minor myopic correction, we’re more inclined to use the excimer laser. We can do low corrections on patients pretty easily. We’ll often look at those patients and do a postop LASIK or PRK procedure to manage an issue without having to return to the OR to address it intraocularly.”

Dr. Kontos believes a lens exchange is appropriate if the myopic postop correction is more than 2 D off-target. “If we have myopia under 2 D, whether we do a lens exchange depends on how the patient feels,” he explains. “Sometimes, patients in this category will think the wrong lenes are in their eyes. And if they have that concept in their minds, exchanging the lens may be the only thing that will make them feel better. For hyperopic patients, I might consider a lens exchange under 1 D, but certainly more than 1 D. Quality of vision is just going to be better with a lens exchange for these patients.”

Dr. Kontos says the use of today’s advanced technologies, such as the IOL Master 700 (Zeiss), has reduced the likelihood of a significant myopic surprise. “But if it were to occur, say in a post-RK patient, or some post-LASIK patient for whom we get a big surprise, then we would do a lens exchange without hesitation,” he says.

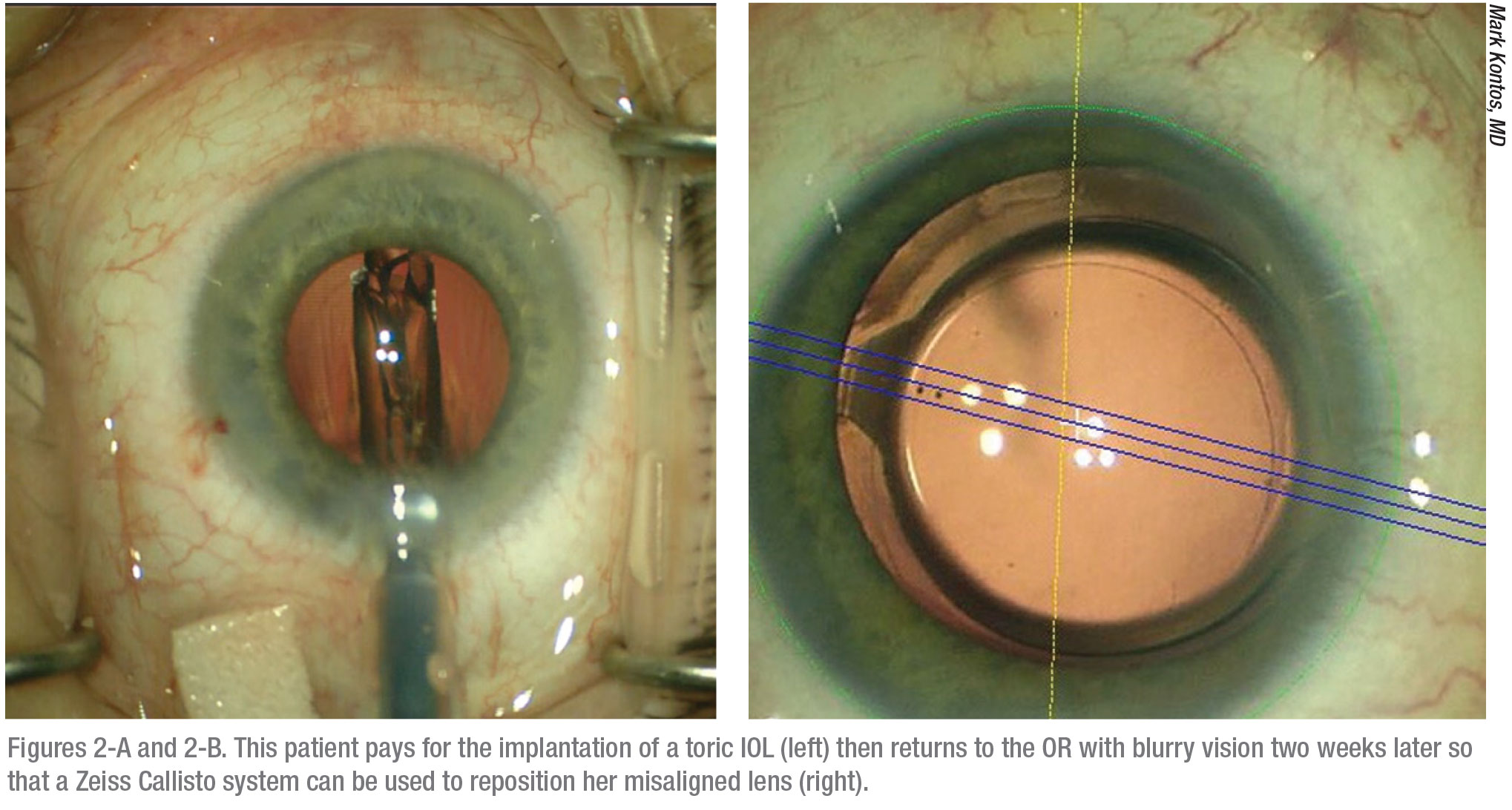

Like Dr. Ayres, Dr. Kontos returns his patient to the OR if he confirms an axis rotation issue in a toric IOL. “We find these issues are generally quick and easy to manage,” he notes. “We’ll take them back to the OR and realign the toric lens. Or, if need be, we’ll exchange that lens.”

In most cases, however, Dr. Kontos and his colleagues try to avoid a repeat trip to the OR for the same eye. “It’s pretty hard to take a patient back for a second time for the same eye,” he reflects. “Most patients will feel as if their surgery didn’t go as planned, obviously. If we can just say, ‘Hey, we can provide a minor laser treatment to do a little touch up on you, and we’ll get you right were we want you to be, it seems more like a simple matter that’s more acceptable to patients, like a contingency plan we’ve already developed.”

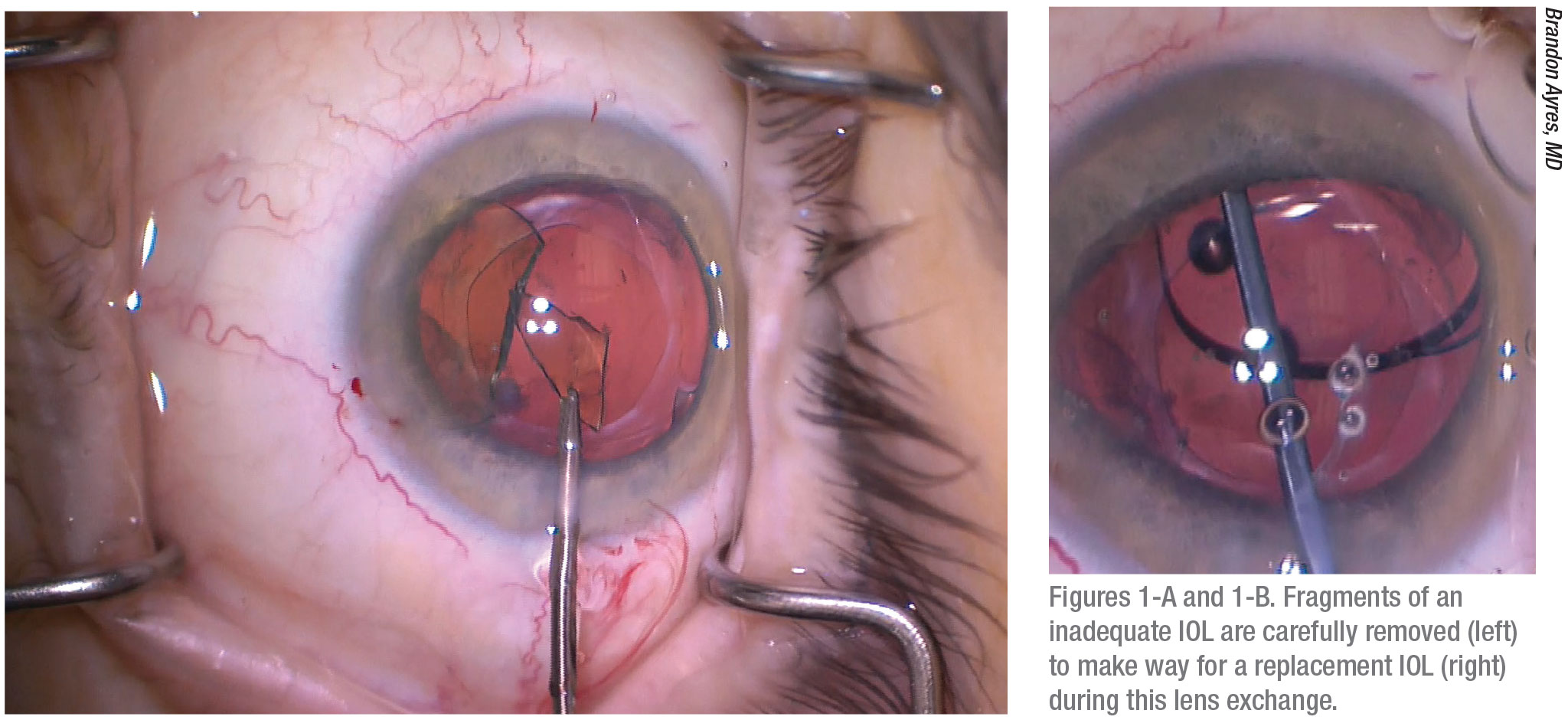

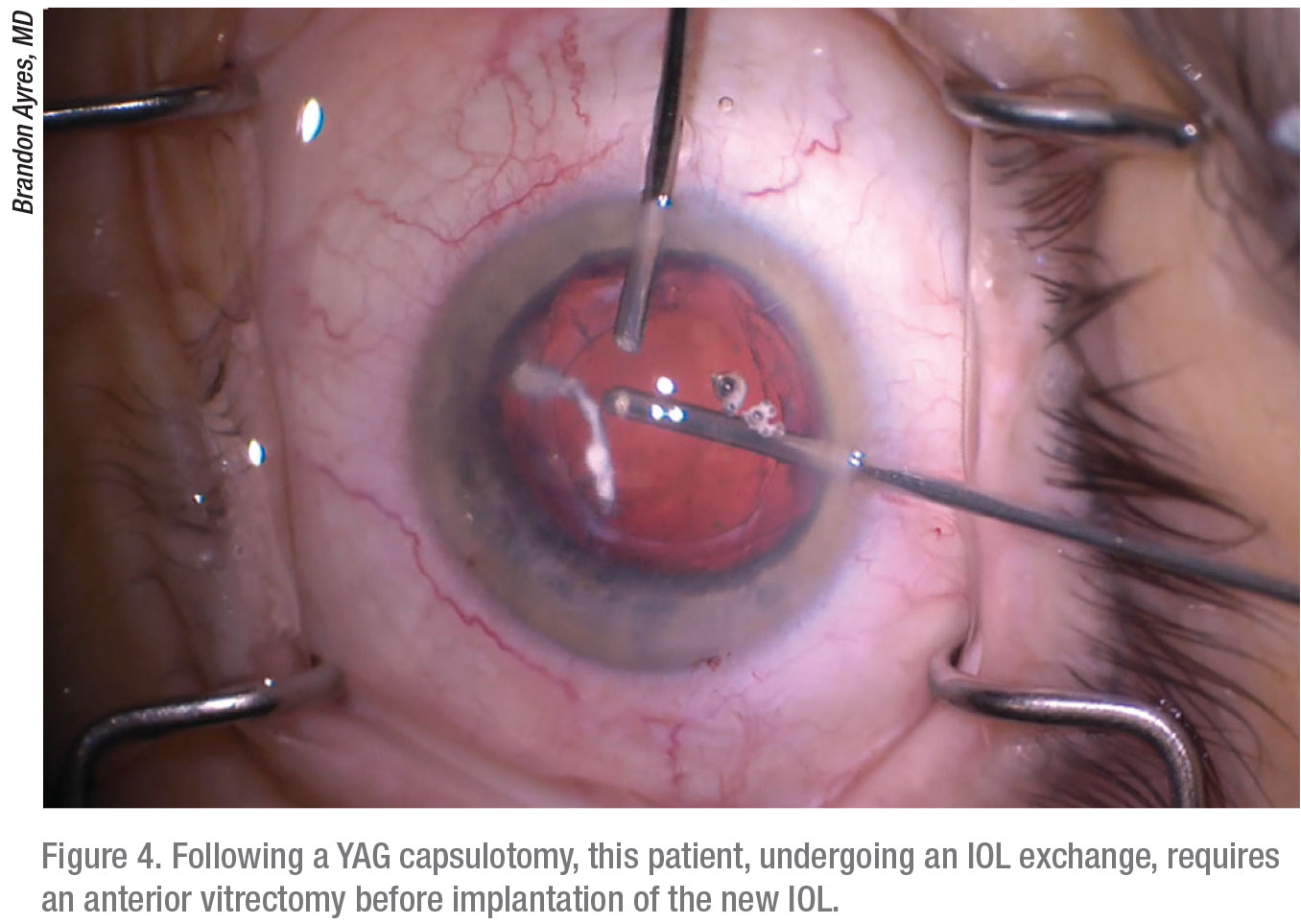

Dr. Ayres says he and his colleagues usually succeed in avoiding unwanted second surgeries. But inevitably? “You’ll have the patients who—no matter what you do—are just not happy with the quality of their vision,” he says. “They’ve tried glasses, maybe even undergone refractive surgery, been on Restasis or Xiidra or any other fill-in-the-blank treatment for dry eye, and they’re just not happy with the quality of their vision. Often, these patients find it difficult to see with good contrast. These are the patients for whom we’ll do a lens exchange. Every so often, they will have already undergone a YAG capsulotomy to treat a little bit of a PCO. So we have to be ready to do a vitrectomy. Usually, though, these patients will do very well.”

After exchanging an IOL, Dr. Ayres recommends waiting to evaluate the result of the procedure before performing an exchange on the fellow eye. “Very often, for unhappy bilateral multifocal implant patients, when we exchange a lens in one eye, we find the exchange seems to reduce dysphotopsia to the extent that they’re happy enough and we opt to leave the second eye alone,” he says. “They realize they have some near vision from that second eye, helping them function as if they have monovision. And to me, that’s a happy patient.”

Residual Refractive Error

Like other surgeons, Dr. Gupta says residual refractive error, potentially developing for a number of reasons, can be a significant source of postop unhappiness among the patients. “There can be errors in biometry,” says Dr. Gupta. “Of course, we do all the tests, but how the lens actually fits into the eye and functions isn’t always predictable. That’s when the art of cataract surgery comes into play.”

She outlines what she calls the “nuts and bolts” of teasing out issues affecting an unhappy postop cataract patient. “My rule of thumb: I like to check the patient at regular intervals to make sure the refractive error is stable,” she says. “For a relatively small refractive error, such as 1 D to 2 D, generally speaking, I find laser vision correction, achieved with PRK or LASIK, can be an excellent treatment. For patients with larger refractive errors, an IOL exchange any time within the first three to six months postop is reasonable. An IOL exchange is also a reasonable option for patients with multifocal lenses who really can’t tolerate the halos, for whatever reason.”

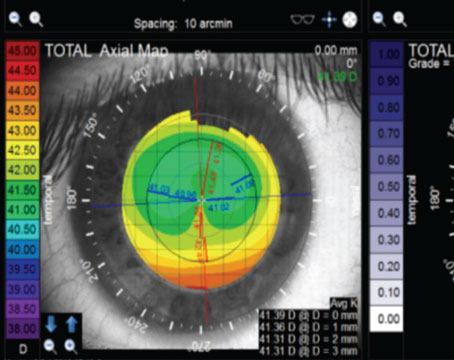

In some cases, Dr. Gupta says the unhappy patients have aberrated corneas from subclinical pathology that wasn’t recognized at the time of surgery. “I go step by step through a detailed examination of the patient’s anatomy, often using topography. I also prefer a dilated exam to make sure we haven’t missed any retinal pathology, such as macular degeneration, epiretinal membrane or macular edema.”

In addition, she looks for abnormalities in the cornea. While surface-related pathology is generally easier to recognize and treat, she notes: “I sometimes feel a need to refer a patient for specialty contact lens fitting. By then, we typically will have identified aberrations, combining topography with tomography, to document information on the shape of the cornea.

“If a patient gets fitted with hard contact lenses and their vision improves, the fitting takes on a diagnostic function because it’s safe to assume that the aberrations were indeed the cause of the visual complaint,” she continues. “If the patient can tolerate the contact lenses, this approach can also become therapeutic. Many of these patients can wear hard contact lenses, which are able to reshape the aberrated cornea, permitting light to enter the eye when the light is bent in a regular pattern.”

However, not all patients with aberrations find themselves with better vision from hard contact lenses. “These cases are harder for us to solve because there really isn’t anything to go back to surgically,” says Dr. Gupta. “We don’t have a technology that can necessarily selectively treat corneal aberrations.”

When surgeons discuss the ways to keep postop cataract patients happy, the idea of implanting IOLs on top of IOLs—the “piggyback” approach—doesn’t come up as much as in years past. Dr. Gupta says piggyback IOLs are “certainly an option, but one that isn’t used very often.” She adds: “Piggyback lenses may be used for patients who are very myopic or very hyperopic. In those cases, you may have no additional IOL powers that will allow them to benefit from a simple IOL exchange. So these are the patients who most often benefit from piggyback lenses.”

|

Premium Challenges

As Dr. Ayres mentioned, surgeons put themselves most at risk of creating unhappy patients when implanting premium IOLs, raising the expectations of patients who may demand more performance than is possible from a lens. “I’m very open and up-front with my patients about premium lenses,” says Dr. Ayres. “I’ll say that the more modern generation of trifocal implants have been performing much better, with a lower complication rate and dissatisfaction rate, than the prior IOLs. The newer technology has really made it easier for us to meet the highest of patient expectations.”

Besides relying on advanced technology, his additional strategy for keeping this cohort of high-spending and high-maintenance patients satisfied is his direct approach. “I always involve my patients in decisions and tell them what’s going on with their surgery,” he explains. “I tell them that what they’re paying for isn’t necessarily a better lens. It’s decreased dependence on reading glasses. We’re not talking about putting in an inferior lens if they opt to not go with the trifocal IOL and instead just choose another quality lens from several good options. Then, the issue is how close the measurements are and how close to plano we can get them, although none of my patients would want to end up at zero.”

|

After implanting the first premium IOL for a patient, Dr. Ayres schedules a follow-up visit one week later to make sure his patient is happy with his or her vision, mindful that he’s typically planning for both eyes. “We need to confirm that the patient wants to continue with this newer technology for the second IOL implant,” he says. “If the patient’s not happy, then we deal with the issue right then and there. That’s when we might decide to use that second surgical date, already scheduled, to do a lens exchange, if one is needed. If our biometry was off, or we just have to slow our plan down and treat a dry-eye problem—whatever the issue—right then is when we plan what we’re going to do. Or we take care of whatever needs to be addressed to satisfy the patient. We like to have the patients help determine what’s going to happen next, so they don’t feel forced into something they don’t want to do.”

And if the patient is unforgiving? Drs. Ayres recommends you consider the following explanations, without making it seem that you’ve done something wrong:

• Measuring the eye before surgery is not an exact science. “Patients need to understand how difficult this can be and how we try to do our best on that first shot,” says Dr. Ayres. “We don’t always get precise measurements.”

• Implants only come in certain sizes, requiring surgeons to estimate the best fit for a patient’s eyes. “We only have 20-mm, 25-mm and 30-mm lenses,” he explains. “The patient’s measurement may actually be at 20.75. So we need to take a best-fit approach. Truth be told, with the benefits of neuroadaptation and other approaches, I usually have these patients worked out within six months. But I prefer to do a lens exchange if we’re off by a significant amount. If the biometry is off, I can exchange even a premium lens without charging the patient.” If you end up needing to replace an IOL, Dr. Ayres notes that you can bill under the diagnosis of dysphotopsia.

• Laser vision correction is just part of the plan. “It’s always possible that you’ll get to a point when laser vision correction is necessary,” says Dr. Ayres. “I tell patients this during the first surgical visit, so they’re not surprised if it becomes necessary. I assure them that if we need to use an approach that’s safer or better for achieving best correction, then we can go with the laser, which I offer at cost. They understand I’m not trying to make more money on them. I’m just trying to ensure that we achieve the highest quality of vision possible.”

When to Charge for More

Dr. Kontos says the decision on whether unhappy postop patients should be required to pay for procedures after the initial surgery depends on what he and his patient have agreed on before surgery. “If patients ask for clear distance vision and we’re incorporating the femtosecond laser into their procedures to correct astigmatism, and we’re doing some additional imaging and taking other steps to make sure we get them to plano, we consider the fact that these patients are already paying out of pocket for the surgery,” he notes. “If we need to do any further work, then we don’t charge those patients.”

Dr. Kontos says the patients who come to his practice fall into three categories:

1. Those who plan to get only what insurance will cover and who want the surgeon to “do the best you can for me.”

2. Those who want to see distance clearly and settle for reading glasses for near vision.

3. Those who want as much independence from their glasses as they can get, such as those who would pay extra for a multifocal or EDOF IOL.

“Patients will pick one of these options and we’ll manage them accordingly,” says Dr. Kontos. “One of the things that’s hard is when a patient comes in after a friend has had surgery and the friend doesn’t need to wear glasses for distance anymore. The friend might see great and was able to use only his health insurance to pay for the surgery, without incurring any expenses beyond the standard co-payment. Now my patient, the friend of the completely satisfied patient, wants the same treatment from me, but he has 1.5 D of cylinder. Unless I do something special to correct that, I’m just not going to satisfy the patient to the extent that his friend was satisfied. This is where that preop discussion becomes so important. If you don’t educate the patient and agree on realistic goals, you’re setting up a patient for unhappiness after surgery.”

Dr. Ayres says his practice keeps its premium cataract surgery cost lower than other practices. “That’s why we do laser vision correction at cost, if we need to do it,” he adds. Other practices bundle that potential laser enhancement cost within the price of their premium cataract surgery. So that enhancement, if necessary, is offered free by those practices.

“Whether you charge or how much you charge for the laser also depends on whether you own the laser or if you have to use a laser center or if someone else is doing the laser treatment for you,” he explains. “Because we try to be very accurate with the use of our biometry, we may only need to offer a refractive surgery enhancement for one in 20 patients. We don’t want to bundle in the cost of a laser treatment that won’t be used for those 19 other patients. That wouldn’t be fair.”

|

Stand by Your Patient

From a clinician’s standpoint, surgeons agree that your top priority when you have an unhappy cataract patient is to always to stand by the patient’s side. “At the very least, promise the patient that you’re going to help work through the problem,” says Dr. Gupta. “I think when patients get shuffled through the process or feel like someone isn’t hearing them, that’s when it becomes a less manageable situation. Most patients are reasonable and can understand that not everything can be the best at all times. But they still want to make sure that surgeons are doing their best to keep them at the top of mind.” REVIEW

Dr. Ayres is a consultant for Alcon, Carl Zeiss Meditech and Microsurgical Technology. Dr. Kontos is a consultant for Zeiss, Sun, Allergan and J & J Vision. Dr. Gupta is a consultant for Alcon.

1. Gibbons A, Ali TK, Waren DP, Donaldson KE. Causes and correction of dissatisfaction after implantation of presbyopia-correcting intraocular lenses. Clin Ophthalmol 2016:11;10:1965-1970.