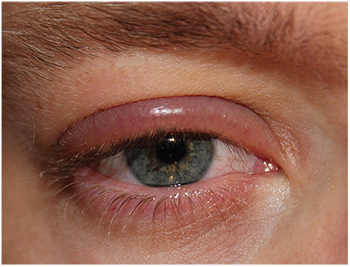

In 1946, ophthalmologist Phillips Thygeson described blepharitis as a chronic inflammation of the lid border and, oddly enough, identified the condition as one of the most common causes of disability observed in military air crew personnel. Patients can present with a range of signs and symptoms that include swelling and crusting of the eyelid and palpebral conjunctiva; superficial keratitis; dry eye; itching; burning; photophobia; incomplete blinks; vision loss and asthenopia.1,3

In this article, we’ll examine the classification and prevalence of blepharitis, look at its presentation and diagnosis, describe some associated conditions, and then discuss current and promising new treatment modalities for controlling symptoms and minimizing complications.

|

| The symptoms and causes of blepharitis can overlap with many disorders, complicating the clinician’s diagnosis and treatment plan. |

Blepharitis, defined simply as inflammation of the eyelids, can affect all age and ethnic groups.4,5 In a survey of U.S. ophthalmologists and optometrists, 37 to 47 percent of their patients had signs of blepharitis.4 However, there is very little reliable data on the true prevalence of blepharitis and the manner in which clinicians manage the condition. One single-center study of 90 patients with chronic blepharitis found that the mean age of patients was 50 years.6 In a case-control study, staphylococcal blepharitis occurred more commonly in women and had an average age of onset of approximately 42 years.7,8 In the same study, the mean age of participants with seborrheic blepharitis was about 50. There was no difference in prevalence between men and women.7

The etiology of blepharitis can be described in several different ways, but in the clinical setting, patients don’t fall neatly into categories. Evaluations of structural and functional changes to the lid margin, ocular surface, meibomian and accessory glands, as well as measures of tear-film stability and location of inflammation may be the best approaches to properly diagnose the disease. Dr. Thygeson’s early description of the etiology of blepharitis classified it into three main types: seborrheic; staphylococcic; and mixed.3,9 Dallas ophthalmologist James McCulley updated this to include six categories: staphylococcal; pure seborrheic; seborrheic associated with a staphylococcal component; seborrheic with secondary meibomian seborrhea; seborrheic with secondary meibomitis; and meibomian keratoconjunctivitis.8 Another, more recent effort created a classification system for blepharitis and dry eye that emphasized the role of meibomian gland dysfunction.10

These efforts to classify and categorize highlight the heterogeneity of the disease etiology and help to explain the therapeutic challenges posed by the disease. In 2006, the research group at Ora developed a structure-specific and clinically relevant photographic scale for evaluating signs and symptoms of blepharitis and meibomitis. This seven-item scale provides investigator grading for lid margin redness and bulbar and palpebral conjunctival redness on a scale of zero to 3 (corresponding to gradings of none to severe), as well as subject-reported signs and symptoms (lid swelling, itchy eyelids and gritty eyes). This grading scale is suitable for the Food and Drug Administration development process of therapeutics and has now become an accepted industry standard.

Organisms such as Demodex mites have also been implicated in the development of blepharitis in some cases. Infestation, characterized by cylindrical dandruff or sleeves around the eyelashes, has been found in 30 percent of patients with chronic blepharitis. These mites live in the eyelash follicles; their eggs and decomposing bodies can clog the follicles and meibomian glands and cause an inflammatory response.11

Colonization of the eyelid by bacteria such as staphylococcus also plays a role in blepharitis; although this and other bacterial species are resident in both healthy and blepharitic eyelids, overgrowth is common in blepharitic eyelids.12,13 Comparisons of bacterial flora between normal eyes and those diagnosed with staphylococcal blepharitis show that only 8 percent of normal patients had cultures positive for Staphylococcus aureus, as compared to 46 to 51 percent of those with staphylococcal blepharitis.14 We know that normally non-pathogenic bacteria may become virulent if their population increases sufficiently. Staphylococcus epidermidis, one of the types of bacteria most often found on the eyelids, can produce inflammation-mediating virulence factors known as phenol-soluble modulins. PSMs are produced at the late stage of infection, leading to the production of inflammatory cytokines and the calling of neutrophils into the tissue.15,16

Presentation and Diagnosis

Unfortunately, the symptoms and causes of blepharitis often overlap with a range of disorders that can complicate diagnosis and treatment. A patient history that includes symptoms associated with systemic disease (e.g., lupus erythematosus, scleroderma), recent systemic and topical medications, and contact lens use is important in determining the diagnosis.17 Some patients can be asymptomatic, while others experience a burning sensation, foreign body sensation, contact lens intolerance or photophobia. The patients’ symptoms are usually worse in the morning, and the disease may be characterized by cycles of exacerbations and remissions.

Staphylococcal blepharitis is recognized under the slit lamp by erythema, edema and irregular eyelid margins, all of which disrupt normal blink patterns, especially with incomplete blinks, resulting in dry spots, disruption of the tear film and inferior punctate keratitis. Telangiectasia can also be seen on the eyelid.

If the condition is mild, scales at the lash line may form collarettes or cuffs of fibrin (appearing as matted, hard scales), which encircle the lash at the base. Keratinization appears as a greasy coating, and lashes may be missing or broken (madarosis), suggesting folliculitis.

In severe and long-standing cases, the lid margin may be irregular due to fibrosis and thickening of the lid, trichiasis (misdirection of eyelashes toward the eye), poliosis (depigmentation of the eyelashes) and eyelid ulceration and damage to the meibomian glands.4,9 Seborrheic blepharitis presents with less erythema, edema and telangiectasia of the lid margins than staphylococcal blepharitis, but with an increased production of sebum and crusting on the lashes.7

Meibomian gland dysfunction is often present in these patients, and is characterized by inflammatory changes at the eyelid margins, in the structural anatomy of the gland orifices, and in the character of the glands’ lipid secretions. The opening to the meibomian glands may develop an operculum with a pouting appearance, while the orifices may become keratinized, obstructed and scarred. Due to gland dropout, secretions may diminish, giving the appearance of infection with their thickened consistency and opaque color.18-22 Lid scarring may also be present in some patients, leading to retraction of the orifice such that secretions are not delivered where they are needed. An irregular lid margin combined with a decrease in meibomian gland secretion can alter the tear-film composition, leading to the dry-eye syndrome that so often occurs in tandem with blepharitis.23

Before the clinician can make a diagnosis of blepharitis, it’s important to rule out conditions that mimic the lid disease’s signs and symptoms. Associated conditions like dry-eye syndrome, chalazia, acne rosacea, allergic conjunctivitis, demodicosis and ocular pemphigoid should all be considered.24

In addition, clinicians should be on the lookout for lesser-known systemic conditions associated with blepharitis such as hormonal dysregulation, certain cardiovascular conditions, inflammatory diseases, imbalance of gastrointestinal tract flora and psychological stress. A better understanding of the pathophysiologic association between those diseases and blepharitis may help in the treatment and prevention of blepharitis.

| The goal of treating inflammation in blepharitis with a topical steroid is a rapid, potent suppressive burst that will quiet the eye in a window of time that’s too brief for the well-known adverse effects of steroids to develop. |

Managing blepharitis relies heavily on the patient-doctor relationship. Treatment is based on the practice of careful lid hygiene, possibly combined with the use of topical antibiotics, with or without topical steroids or topical anti-inflammatory agents. Systemic antibiotics may be appropriate in some patients.

Initial treatment is eyelid hygiene, which includes lid scrubs, warm compresses and lid massage. Warm compresses raise the temperature of the eyelid above the melting point for meibomian gland secretions, thus aiding in secretion.

Massage can enhance the flow of secretions from the meibomian glands. To perform it, the patient holds the lid at the outer corner with one hand while the index finger of the other hand applies pressure and sweeps from the inner corner of the lid toward the ear.

Eyelid scrubs, which involve just a gentle scrubbing of the eyelids twice daily with a wet washcloth and detergent such as baby shampoo applied with a cotton-tipped swab applicator, are performed after the warm compresses to clear away crusts (scale and debris) that have accumulated on the eyelid margin.25 If the crusts are difficult to remove, warm compresses can be applied two to four times daily with a washcloth at 10-minute intervals to soften and loosen encrustations and warm the secretions. Blepharitis is a chronic disease, so lid hygiene must be consistent and continue even after an acute exacerbation has resolved.

If substantial inflammation is present, patients may benefit from a short course of treatment with a topical corticosteroid. The goal of treating ocular inflammation is a rapid and potent suppressive burst, an “attack-and-retreat” approach that will successfully quiet the eye in a window of time too brief for developing the well-known adverse effects of steroids.

One such therapy in development is NCX 4251 (Nicox SA; Sophia Antipolis, France) a novel nano-crystalline formulation of fluticasone propionate that utilizes a unique applicator for topical delivery to the eyelid margin. In lymphocyte proliferation assays, fluticasone propionate has been observed to have a tenfold greater immunosuppressive potency than dexamethasone and a hundredfold greater potency than prednisolone acetate, which are currently the two leading ophthalmic steroids. It’s thought that a more potent steroid could effectively quiet an inflamed eye in one- or two-week bursts of therapy, allowing for cessation of the therapy before any side effects ensue.

The proposed route of delivery for this blepharitis product is topical dosing directly to the eyelid with a sterile applicator. This eyelid applicator also features a lid scrubbing movement to aid in the efficacy of the product. The drug’s potency might also allow for once-daily dosing, which would be a significant advantage over other steroid options.

Decreasing bacterial colonization of the lids can be beneficial. A topical antibiotic ointment such as erythromycin or bacitracin may be indicated in some cases; it may be applied after lid hygiene techniques once or twice daily at the base of the eyelashes, depending on the severity of the inflammation.

Patients who do not respond to lid hygiene therapies or those suffering from ocular rosacea may benefit from orally administered tetracyclines. Clinical improvement with tetracycline use may be related to inhibition of bacterial lipases in both S. aureus and S. epidermidis.14 However, tetracyclines may cause photosensitivity and should not be used orally in pregnant or lactating women or children younger than 8 years old because of the risk of tooth enamel abnormalities.24

In 2011, ophthalmologist Gail Torkildsen and her colleagues evaluated the clinical efficacy and safety of a tobramycin and dexamethasone ophthalmic suspension (TobraDex ST, Alcon) compared to azithromycin ophthalmic solution 1% (Azasite, Inspire Pharmaceuticals) in the treatment of moderate to severe blepharitis/blepharoconjunctivitis.26 The study was sponsored by Alcon. The primary outcome parameter of the study was the difference in the seven-item global score (evaluated using standardized Ora scales). This study demonstrated that TobraDex ST was faster than Azasite in controlling the signs and symptoms of acute blepharitis/blepharoconjunctivitis when administered q.i.d. for a week.

Since many blepharitis patients also have both evaporative and aqueous tear deficiency, topical lubrication with artificial tears may improve symptoms when used as an adjunct to eyelid cleansing and medications. The LipiFlow system (TearScience, Morrisville, N.C.) is a novel thermal pulsation approach that applies simultaneous heat and pressure to the eyelid tissue to express the meibomian glands. Jack Greiner, DO, PhD, of the Schepens Eye Research Institute, and his colleagues found that a single 12-minute treatment with the LipiFlow system improved both signs (based on tear breakup time, corneal fluorescein staining and meibomian gland secretion scores) and symptoms (based on Ocular Surface Disease Index and standard patient evaluation of eye dryness scores) of meibomian gland dysfunction for up to one year after the treatment.27

Blepharitis is a common, complex, chronic disease of the eyelids that can present with a range of signs and symptoms. It’s critical that patients and their caregivers remain on the lookout for the signs of blepharitis even after a flare-up is controlled. Careful and consistent lid hygiene, with the occasional use of topical antibiotics with or without topical steroids, remain the mainstays for disease management. Going forward, improvements in technology and diagnostics will help clinicians to better understand the complex manifestations of this disease, ultimately aiding in the future development of customizable treatment plans.

With eyelids standing as the guardians of our most precious sense, encouraging sensible lid hygiene and prompt response to blepharitis outbreaks seems a small price to pay for ocular health. REVIEW

Dr. Abelson is a clinical professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School. Mr. Shapiro is vice president at Ora, where Mr. Rimmer is a medical writer. Dr. Abelson may be reached at MarkAbelsonMD@gmail.com.

1. McCulley JP, Shine WE. Eyelid disorders: The meibomian gland, blepharitis, and contact lenses. Eye & Contact Lens 2003;29:1:S93-S95.

2. Abelson MB, Reynolds O. Are you missing these common eyelid disorders? Skin and Aging 1998;2:6:48-53.

3. Thygeson P. Etiology and treatment of blepharitis: A study in military personnel. Arch Ophthalmol 1946;36:4:445-477.

4. Lemp MA, Nichols KK. Blepharitis in the United States 2009: A survey-based perspective on prevalence and treatment. Ocul Surf 2009;7:2:S1-S14.

5. Viswalingam M, Rauz S, Morlet N, Dart J. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children: Diagnosis and treatment. Brit J Ophthalmol 2005;89:4:400-403.

6. Schaumberg DA, Nichols JJ, Papas EB, Tong L, Uchino M, Nichols KK. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: Report of the subcommittee on the epidemiology of, and associated risk factors for, MGD. Inv Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:4:1994-2005.

7. McCulley J. Blepharitis associated with acne rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis. Inter Ophthalmol Clin 1985;25:1:159-172.

8.McCulley JP, Dougherty JM, Deneau DG. Classification of chronic blepharitis. Ophthalmology 1982;89:10:1173-1180.

9. Jackson WB. Blepharitis: Current strategies for diagnosis and management. Canad J Ophthalmol 2008;43:2:170-179.

10. Mathers WD, Choi D. Cluster analysis of patients with ocular surface disease, blepharitis, and dry eye. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:11:1700-1704.

11. Kemal M, Sümer Z, Toker MI, Erdogan H, Topalkara A, Akbulut M. The Prevalence of Demodex folliculorum in blepharitis patients and the normal population. Ophthal Epidemiol 2005;12:4:287-290.

12. Groden LR, Murphy B, Rodnite J, Genvert GI. Lid flora in blepharitis. Cornea 1991;10:1:50-53.

13. Valenton MJ, Okumoto M. Toxin-producing strains of staphylococcus epidermidis (albus): Isolates from patients with staphylococcic blepharoconjunctivitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1973;89:3:186-189.

14. Dougherty JM, McCulley JP. Comparative bacteriology of chronic blepharitis. Brit J Ophthalmol 1984;68:8:524-528.

15. Kulaçoglu DN, Özbek A, Uslu H, et al. Comparative lid flora in anterior blepharitis. Turk J Med Sci 2001;31:4:359-363.

16. Schauder S, Bassler BL. The languages of bacteria. Genes & development 2001;15:12:1468-1480.

17. Blepharitis. American Academy of Ophthalmology Retinal Panel. Prefered Practice Guidlines 2008; www.aao.org/ppp. Accessed 24 February 2016.

18. Jester J, Nicolaides N, Kiss-Palvolgyi I, Smith R. Meibomian gland dysfunction II. The role of keratinization in a rabbit model of MGD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1989;30:5:936-945.

19. Jester J, Nicolaides N, Smith R. Meibomian gland dysfunction: Keratin protein expression in normal human and rabbit meibomian glands. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1989;30:5:927-935.

20. Jester JV, Nicolaides N, Smith RE. Meibomian gland studies: Histologic and ultrastructural investigations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1981;20:4:537-547.

21. Robin JB, Jester JV, Nobe J, Nicolaides N, Smith RE. In vivo transillumination biomicroscopy and photography of meibomian gland dysfunction: A clinical study. Ophthalmology 1985;92:10:1423-1426.

22. Gutgesell VJ, Stern GA, Hood CI. Histopathology of meibomian gland dysfunction. Am J Ophthalmol 1982;94:3:383-387.

23. Bowman RW, Dougherty JM, McCulley JP. Chronic blepharitis and dry eyes. Inter Ophthalmol Clin 1987;27:1:27-35.

24. Driver PJ, Lemp MA. Meibomian gland dysfunction. Surv Ophthalmol 1996;40:5:343-367.

25. Geerling G, Tauber J, Baudouin C, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: Report of the subcommittee on management and treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:4:2050-2064.

26. Torkildsen GL, Cockrum P, Meier E, Hammonds WM, Silverstein B, Silverstein S. Evaluation of clinical efficacy and safety of tobramycin/dexamethasone ophthalmic suspension 0.3%/0.05% compared to azithromycin ophthalmic solution 1% in the treatment of moderate to severe acute blepharitis/blepharoconjunctivitis. Curr Med Res Opin 2011;27:1:171-178.

27. Greiner JV. A single LipiFlow thermal pulsation system treatment improves meibomian gland function and reduces dry eye symptoms for 9 months. Curr Eye Res 2012;37:4:272-278.