Our approach to repairing rhegmatogenous retinal detachments has undergone a sea change over the years, moving from the scleral buckling we were taught to use in most cases in the last century to vitrectomy today. The change was made because of factors such as ease of technique and the potential safety benefits of vitrectomy. Don’t discard scleral buckling completely, though, since it may still have a place in our treatment armamentarium.

Here, I’ll describe why vitrectomy has become popular, discuss some finer points of the technique and outline situations where scleral buckling may be preferable.

Vitrectomy vs. Buckling

As I mentioned earlier, in my initial training we tried to repair every retinal detachment with a scleral buckle first, with vitrectomy being a kind of last resort. Now, however, most detachments are repaired with vitrectomies, even in situations in which a vitrectomy might not be the best option.

Why did this change occur? I believe it’s because vitrectomy is a safer, more controlled procedure. Advances in the equipment for vitrectomy are comparable to those advances for cataract surgery; the removal of vitreous and traction on the retina is much less dangerous than it was 30 years ago. Unlike scleral buckling, vitrectomy has evolved, and doesn’t involve the kind of “blind” maneuvers scleral buckling requires, such as the external drainage of subretinal fluid. Also, vitrectomy doesn’t alter the shape of the eye the way scleral buckling does. Buckling patients also occasionally suffer complications such as diplopia due to the buckle being placed beneath the ocular muscles; infection; globe ischemia; and choroidal hemorrhage. Another reason for vitrectomy’s popularity is the fact that retinal specialists perform the procedure for many other reasons, such as macular pucker, macular hole and diabetic retinopathy, so the comfort level of young retinal surgeons is much higher than it is with scleral buckling. Vitrectomy is also very effective: I recently reviewed my last 100 cases of acute retinal detachment repaired by vitrectomy, and 94 of them were successfully repaired with one operation. During this same time period, I performed 43 scleral buckling operations, a ratio of 2/3 in favor of vitrectomy. This is the opposite of the ratio at which they were performed when I finished my fellowship.

Researchers have compared these surgical approaches as well. In a prospective, randomized, multicenter clinical trial, the Scleral Buckling versus Primary Vitrectomy in Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment Study, 45 surgeons at 25 centers in Europe recruited 416 phakic and 265 pseudophakic retinal detachment patients over a five-year period. There was one-year follow up in the study, and the primary outcome (change in best-corrected visual acuity) was assessed at one year.

Secondary endpoints were primary and final anatomical success, occurrence of proliferative vitreoretinopathy, cataract progression and the number of reoperations.

In the phakic trial, the mean BCVA change was significantly greater in the buckling group (p=0.0005) (SB: -0.71 ±0.68 logMAR [around a seven-line improvement in Snellen vision]; PPV: -0.56 ±0.76 logMAR [around a five-line improvement]). In the pseudophakic trial, changes in BCVA showed a nonsignificant difference of 0.09 logMAR. In phakic patients, cataract progression was greater in the PPV group (p<0.00005).

In the pseudophakic group, the primary anatomical success rate (defined as retinal reattachment without any secondary retina-affecting surgery) was significantly better in the vitrectomy group (SB: 71/133 [53.4 percent]; PPV: 95/132 [72 percent]) (p=0.0020). In pseudophakes, the mean number of retina-affecting secondary surgeries was lower in the vitrectomy group (SB: 0.77 ±1.08; PPV: 0.43 ±0.85; p=0.0032).

In the phakic trial, the redetachment rate in the SB group was 26.3 percent (55/209 patients) and in the vitrectomy group it was 25.1 percent (52/207 patients). The redetachment rate was 39.8 percent for scleral buckling (53/133) and 20 percent for vitrectomy (27/132) in the pseudophakic trial. The study surgeons wrote that buckling shows a benefit in phakic eyes with respect to BCVA improvement. They added, however, that there was no difference in BCVA in pseudophakes and, based on a better anatomical outcome, recommended vitrectomy in these patients.1

The cause of most retinal detachments is acute posterior vitreous detachment with retinal tear or tears, so the correct response is to remove the vitreous and any associated traction on the retina, and to treat the tear or tears. Some patients, however, develop retinal detachment because they have congenital defects in the retina; they are often very myopic, with their retinas stretched out. Pockets of syneretic, liquid vitreous leak through these retinal holes and defects, which causes the retina to separate. These types of patients don’t have a vitreous detachment or vitreous-separation-related detachment. In fact, some of these patients have abnormally adherent vitreoretinal interfaces. For them, I feel the buckle is the better procedure, because it avoids the need to remove clear vitreous and the subsequent increased risk of cataract. I’ve seen cases in which vitrectomy surgery failed because of the inability to detach the vitreous from the retina. In such cases, the patient sometimes winds up undergoing multiple operations, having extensive relaxing retinectomies, and developing a host of other complications, such as corneal edema, secondary glaucoma, subconjunctival oil, and ultimately, very poor final vision even if the retina is eventually “successfully re-attached.”

My Surgical Approach

Accompanying vitrectomy’s surge in popularity has come a new appreciation for the maneuvers necessary for success. Here are some guidelines I follow and the techniques I employ:

• Overall goals. The main thing is to adequately remove the vitreous and make sure you have adequate posterior vitreous separation, especially around the retinal breaks. I try to separate the hyaloid all the way to the vitreous base. Especially in a younger patient, who doesn’t necessarily have a vitreous detachment, you have to make sure you remove the vitreous from the retina in order to have a higher success rate. Also, when you’re performing the vitrectomy, it’s helpful to shave the vitreous down as thoroughly as possible at the vitreous base. I think that this might reduce circumferential traction and reduce the need for scleral buckling.

• Laser tips. After I’ve completely removed all the vitreous, and drained the fluid through the posterior retinotomy to flatten the retina, I’ll perform peripheral laser to treat all the retina tears. I don’t necessarily always perform 360-degree laser, though some surgeons do. I usually treat the peripheral retina for the entire extent of the retinal detachment, and any additional areas of obvious retinal pathology such as lattice degeneration or atrophic holes. In addition, I treat to the ora serrata in any area that I do treat. I prefer lighter laser burns, enough to create a chorioretinal scar, but not too intense to cause retinal shrinkage, which, I feel, might later lead to breaks at the edge of laser-treated areas and recurrent detachment.

|

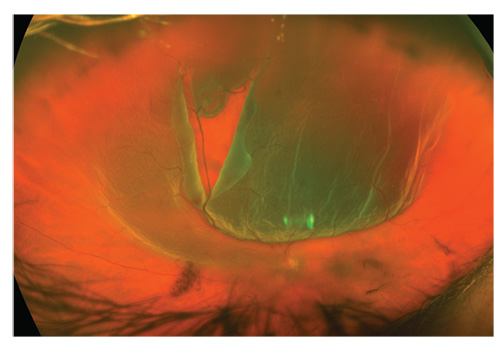

| A 50-year-old patient with sudden loss of vision is his only eye. Visible are the posterior vitreous detachment, vitreous hemorrhage and a large, posteriorly extending retinal tear. |

I laser the posterior retinotomy last after removing any additional vitreous and subretinal fluid that may have accumulated posteriorly while I was doing the peripheral laser. I feel I can get better drainage of subretinal and intravitreal fluid, and better gas fill in the vitreous cavity if I do this last.

It should be noted that some surgeons don’t laser the drainage retinotomy, and that’s reasonable—we don’t laser macular holes, after all. This is because the retinotomy is pretty small, posteriorly located and presumably there isn’t any vitreous traction around the break, so some don’t feel it’s necessary to add a chorioretinal scar in a posterior location by treating the retinotomy with laser.

• Closing the case. I usually close my sclerostomies with sutures in most cases, especially if it’s an inferior detachment. This gives me a better gas fill; because of the additional manipulation involved with doing a more thorough vitrectomy, and because many patients with retinal detachments are myopes and have thinner scleras, my sclerostomies tend to leak in retinal detachment cases, unlike macular pucker or macular hole cases. I almost always use C3F8 gas. Occasionally because of air travel considerations or the need for quick visual rehabilitation because the patient is monocular in the eye with the detachment, I will use SF6 or silicone oil. I use 7-0 chromic gut for gas cases and 7-0 vicryl for oil cases.

Scleral Buckling Technique

I dislike doing scleral buckling procedures. I like it less the more presbyopic I become. It is useful in some cases, however. Here are things to keep in mind when you perform the procedure.

• Adding a buckle during vitrectomy. Though vitrectomy is a very good procedure, as mentioned earlier there are some cases that can potentially benefit from the addition of scleral buckling. For example, if the eye is phakic, you’re usually inclined to be less aggressive in terms of dissecting the vitreous base and getting the anterior vitreous off as thoroughly as possible out of fear of inducing immediate cataract. A buckle gives you the ability to be a little less aggressive and thorough with your vitrectomy, allowing you to get away with not getting all the vitreous off. Also, if I see signs of early proliferative vitreoretinopathy and the retina is somewhat stiff, putting an encircling band around the eye might help prevent recurrent detachments, or at least I sleep better at night knowing that I have done everything I could have for the eye. Again, this is infrequent as I include scleral buckling on only 10 percent of my vitrectomy cases. When I do, I use a 41 band and typically place the buckling element to support the vitreous base or broad areas of lattice where the vitreous may be difficult to separate from the retina.

• Scleral buckling alone. Scleral buckling is definitely the correct procedure in patients (typically younger) without vitreous detachment who might have retinal dialysis or retinal holes with or without associated lattice degeneration. When performing scleral buckling surgery, I just want to avoid complications, such inadvertent scleral perforation while passing the mattress sutures, or causing subretinal hemorrhage when I drain the subretinal fluid. I rarely do segmental buckles now, except for retinal dialysis. My thinking is that these patients probably have abnormal areas of retina or vitreoretinal adhesions that I can’t see, and encircling the eye provides me with the security that the entire peripheral retina is supported, and a seemingly normal area will not detach in the future. I usually encircle with a silicone sponge as this seems to give me better scleral indentation and elevation with less induced myopia than a silicone band.

|

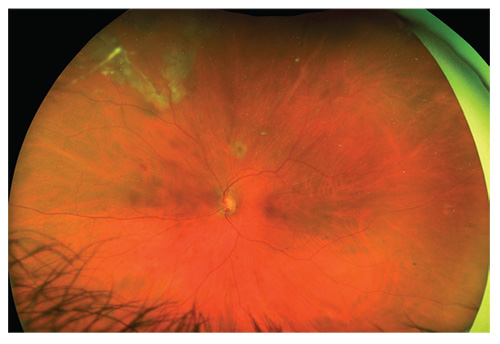

| The retina from the previous page, one week postop. Silicone oil was used to allow the patient to see immediately. |

• External drainage of subretinal fluid. For this step of the procedure, I usually use a short 25-gauge needle and put the needle in just past the angle of the tip. I drain in the bed of the buckle and in an area that has been treated with cryotherapy and, obviously, where the retina is most detached. I do this after I have placed the buckle and tightened the mattress sutures temporarily. This provides increased pressure in the eye to allow subretinal fluid to egress through a very small puncture wound and prevents excessive hypotony during drainage that can increase choroidal hemorrhage. In addition, if I inadvertently perforate the retina, which shouldn’t occur, the hole that is created has already been treated and is supported by the buckle. My main goal of performing drainage is to soften the eye sufficiently to get enough elevation of the scleral buckling element to close the holes without causing central retinal artery occlusion. “Complete” drainage is not a goal and is rarely achieved, especially when the patient is evaluated with OCT.

Pneumatic Retinopexy

Pneumatic retinopexy is another approach to retinal detachment repair. It is a less-involved office procedure compared to vitrectomy or scleral buckle, and produces very good results in a recent paper.2 In PR, a gas bubble is injected into the vitreous cavity that closes the retinal break and allows the the detached retina to re-attach. Cryotherapy can be performed in detached retina to create a chorioretinal adhesion around the tear before the gas bubble injection, or laser can be performed to the tear or tears after the gas bubble has re-attached the retina. In the recent study, 176 detachment patients were randomized to either the PR or PPV. The primary outcome was one-year ETDRS visual acuity. Important secondary outcomes were subjective visual function (NEI VFQ-25), metamorphopsia score (M-CHARTS) and primary anatomical success.

ETDRS visual acuity following pneumatic retinopexy exceeded vitrectomy by 4.9 letters at 12 months (79.9 ±10.4 versus 75 ±15.2, p=0.024). Mean ETDRS visual acuity was also superior for the pneumatic retinopexy group compared to vitrectomy at three months (78.4±12.3 versus 68.5 ±17.8) and six months (79.2 ±11.1 versus 68.6 ±17.2). Composite NEI VFQ-25 scores were superior for pneumatic retinopexy at three and six months. Also, vertical metamorphopsia scores were superior for the PR group compared to vitrectomy at 12 months (0.14 ±0.29 versus 0.28 ±0.42, p=0.026). Primary anatomical success at 12 months was achieved by 80.8 percent of patients undergoing PR versus 93.2 percent undergoing vitrectomy (p=0.045), with 98.7 percent and 98.6 percent, respectively, achieving secondary anatomical success. Sixty-five percent of phakic patients in the vitrectomy arm underwent cataract surgery in the study eye before 12 months, versus 16 percent for PR (p<0.001).

For my part, I do a fair number of pneumatic retinopexies and offer the procedure to patients when it’s appropriate. Superior detachments with a single break or breaks near the same location, and minimal additional pathology are good candidates for it. Unfortunately, many people who develop detachments have retinas that are less than perfect, with areas of lattice degeneration and holes, and therefore aren’t suitable for the procedure. It’s great when it works, but the success rate is 70 to 80 percent even in ideal candidates.

I hope the techniques I’ve shared help improve your understanding of the current approach to retinal detachment, or even enhance your current technique. Vitrectomy has been a great alternative to the broad use of scleral buckling, though it’s important for ophthalmologists to know that the latter procedure still has a very important place in our arsenal. REVIEW

Dr. Wong is in private practice with Retinal Consultants of Houston. He has no financial interest in any product mentioned in the article.

1. Heimann H, Bartz-Schmidt KU, Bornfeld N, et al. Scleral buckling versus primary vitrectomy in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: A prospective randomized multicenter clinical study. Ophthalmology 2007;114:12:2142-54.

2. Hillier RJ, Felfeli T, Berger AR, et al. The Pneumatic Retinopexy versus Vitrectomy for the Management of Primary Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment Outcomes Randomized Trial (PIVOT). Ophthalmology 2018 Nov 20. [Epub ahead of print]