Like many ophthalmic problems, uveitis can be a challenge for clinicians. It has numerous possible etiologies that require different treatment approaches, and every patient is unique; there’s currently no way to be sure how the patient seated in front of you will react to a given treatment. The practical result is that addressing uveitis requires a lot of trial and error, ruling out possible causes to avoid inappropriate treatment, and then working your way through a series of options to find the right treatment—or combination of treatments—that will bring your patient relief and preserve vision.

Here, surgeons with extensive experience managing these patients offer their advice.

Ruling Out Infection

Surgeons agree that the first step in addressing uveitis is determining the cause of the problem. “One reason that managing uveitis is challenging is that up to half of the cases are idiopathic,” notes Priya Janardhana, MD, director of the uveitis service and an assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester. “However, we know that uveitis can be caused by autoimmune disease or infectious disease, so it’s important to test patients for these. It’s especially important to rule out infectious causes, because if there’s an infection, we need to treat that before putting a patient on immunosuppressive medications.

“In particular, we have to order tests to rule out sarcoidosis, tuberculosis and syphilis—the ‘masqueraders of the eye’—in every patient,” she says. “I order syphilis testing, both treponemal and nontreponemal testing; quantiferon—PPD is OK—to rule out TB; sarcoidosis labs, both ACE and lysozyme; and a chest X-ray. Then, I order a number of panels to look for autoimmune inflammatory markers. Which specific ones I order will depend on whether the uveitis is anterior, posterior or panuveitis.” Dr. Janardhana adds that it’s OK to start the patient on topical steroid drops while waiting for the lab results to come in.

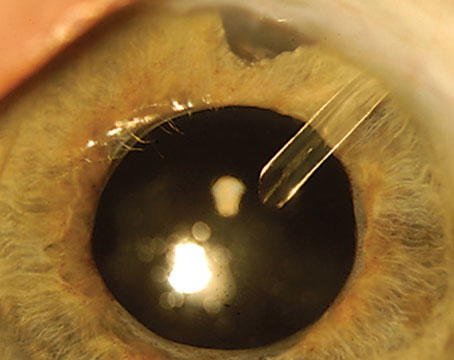

|

|

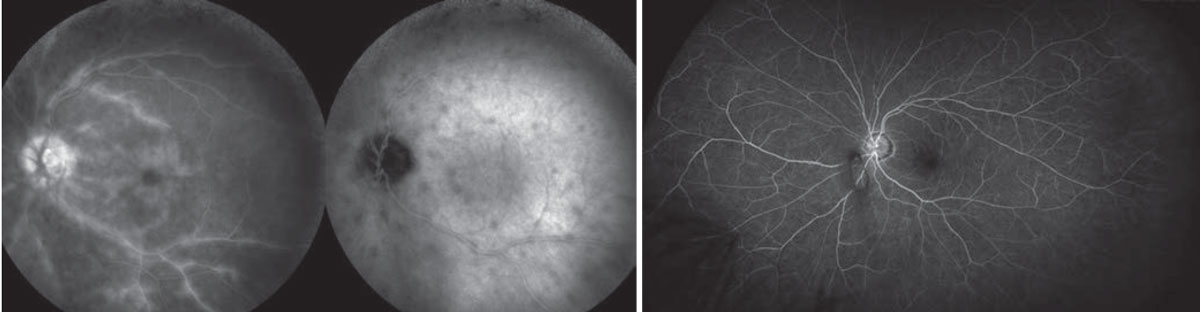

Left: A 43-year-old female diagnosed with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, pretreatment. Right: After tapering a course of oral prednisone as a bridge to treatment with monthly Remicade infusions and weekly methotrexate. Image courtesy of Christopher R. Henry, MD. |

Pauline T. Merrill, MD, a partner at Illinois Retina Associates and an associate professor of ophthalmology at Rush University in Chicago, agrees that the most important thing a clinician should do after discovering uveitis is make 100-percent certain that the uveitis is noninfectious. “This requires a lab workup,” she says. “There’s no way anyone can be certain whether or not the uveitis is infectious just by looking. As a rule of thumb, you should assume it could be syphilis or TB until proven otherwise.”

Dr. Merrill notes that, in some cases, you may be able to identify viral uveitis via a thorough exam. “Always do a complete eye exam before you start thinking about treatment, and be sure to consider viral uveitis,” she says. “A mild iritis in a patient with a history of herpetic infection might respond to topical treatment; but only by dilating and doing a full exam can you make sure that you’re not missing retinitis that could blind the patient if not treated promptly. Clinical signs can be fairly characteristic for some viral presentations such as acute retinal necrosis, but I still often confirm that with PCR testing—in addition to testing for syphilis, of course.”

Dr. Merrill adds that another masquerader you need to consider is intraocular lymphoma, particularly in older patients. “Intraocular lymphoma is rare, but it’s important to rule it out as a cause of vitritis in patients over 50,” she explains.

“The point,” she says, ”is that although most uveitis won’t turn out to be infectious or intraocular lymphoma, the few patients that do have these conditions are the patients who may go blind or worse without proper treatment. That’s why you should always consider the worst possible scenario before deciding how to proceed.”

Treating with Topical Steroids

“Once you’re sure you’re dealing with a noninfectious process, your treatment paradigm depends on three things,” says Christopher R. Henry, MD, a fellowship-trained vitreoretinal surgeon and uveitis specialist who practices at Retina Consultants of Texas, and a clinical assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Houston Methodist Institute for Academic Medicine. “First is chronicity: Has this been a chronic process or an acute process? Second is severity. Is this vision-threatening, or not too severe? Third is bilaterality: Is this a one-eye or two-eye process? If it’s mild, isolated acute uveitis, you can often manage that with topical or local therapy. If it’s chronic, severe, bilateral uveitis you’ll often have to resort to systemic therapy.”

“I typically start with topical steroids while I’m waiting for the lab results,” says Dr. Merrill. “This does a couple of things. First, it may help treat whatever anterior component of the uveitis is present. Durezol (difluprednate ophthalmic emulsion) can also penetrate posteriorly. Second, how the patient’s IOP reacts may give you an idea of whether the patient is a steroid responder. If the pressure goes through the roof on prednisolone four times a day for a few weeks, you’ll think twice before giving that patient a steroid injection.”

| Managing infectious Forms of uveitis Christopher R. Henry, MD, a fellowship-trained vitreoretinal surgeon and uveitis specialist who practices at Retina Consultants of Texas, says the mainstays of treatment for infectious uveitis haven’t changed. “We direct the treatment based on the infectious organism,” he says. “If it’s syphilis, the patient gets IV penicillin; if it’s herpes or shingles, they get valacyclovir; and so on. You verify the infection with either systemic lab serology or—sometimes—direct ocular cultures. Then you tailor your treatment to the organism.” “If the uveitis is infectious, whether viral, bacterial or fungal, we treat with the appropriate antiviral, antibacterial or antifungal medication,” says Priya Janardhana, MD, director of the uveitis service and an assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester. “However, even after treating with the appropriate medication you’ll often still have inflammation that needs to be addressed. If there’s still a lot of inflammation after 48 hours, I start the patient on oral prednisone—as long as there’s good coverage with an antibiotic or antiviral. This is a balancing act; we don’t want to encourage the infection by suppressing the immune system, but the body’s immune system is creating all of this inflammation with its immune cells trying to fight the infection, and that’s what’s actually causing the damage. So we use prednisone to control that aspect of the process while the antibiotic or antiviral is controlling the infection.” “Some of the more interesting things on the horizon for infectious uveitis are in the area of diagnostics,” notes Dr. Henry. “Right now it’s pretty easy to run multiplex PCR to detect viruses like herpes, shingles and cytomegalovirus. But bacterial and fungal cultures traditionally have been done using standard culture plates. It’s currently possible to get bacterial and fungal PCR sequencing through labs such as the University of Washington, but it can be a difficult test to order, and there can be a several-week timeframe to obtain results. In the not-too-distant future, we hope to have more easily accessible PCR tests that can do pan-bacterial and pan-fungal testing, in addition to pan-viral testing.” —CK |

Once infection has been ruled out, Dr. Janardhana also starts the patient on steroids. She explains that her protocol—particularly choosing oral steroids vs. topical drops—is based on numerous factors. “If I only find anterior involvement, or anterior and intermediate involvement, I typically start the patient on just a topical steroid drop such as prednisolone, plus a cycloplegic drop,” she says. “Durezol is a really good medication for anterior and intermediate uveitis. It has very good penetration to the posterior part of the eye. So, for patients who have contraindications to systemic steroids, such as a brittle diabetic patient, this would be a good option. However, it’s important to monitor intraocular pressure carefully and warn patients of the risk of cataract formation with long-term use.”

Steroids Into the Eye

If topical drops are insufficient, most surgeons move on to either systemic steroid treatment or steroid injections into the eye. The latter can be done directly, or via an implant that will deliver a steroid slowly over an extended period.

Dr. Merrill says that what she does after steroid drops depends on the situation. “If the patient just has mild anterior uveitis, drops might be all the patient needs,” she explains. “In that case, you treat intensively at first and then taper slowly. However, a lot of patients don’t improve significantly with topical steroids in a short period of time, or they have more posterior involvement. Those patients will benefit from either local injections or systemic treatment.”

Dr. Janardhana explains that there are several situations in which she might offer steroid injections into the eye. “I may offer the option of a short- or long-acting periocular or intravitreal steroid injection to a patient with unilateral noninfectious uveitis who hasn’t been on oral steroids,” she says. “However, I wouldn’t inject Ozurdex or Triesence into the eye without knowing first whether the patient is a steroid responder, so before I do an injection I always start the patient on topical steroid drops, like prednisolone or Durezol. I’ve seen patients receive an Ozurdex injection without having used topical drops first, and then develop steroid-induced ocular hypertension, and in extreme cases need glaucoma surgery.

“Also,” she adds, “if a patient is taking oral steroids, depending on the type of inflammation and uveitis the patient has, I watch to see if the inflammation comes back as I’m tapering. If it does, I tell the patient that we have to think about systemic therapy, or potentially a steroid injection into the eye.”

Dr. Merrill offers an overview of the steroid-eluting implants. “Starting in 2005 we had the Retisert fluocinolone surgical implant,” she says. “Today we have the Yutiq fluocinolone injectable implant and the Ozurdex dexamethasone implant. Retisert is still useful in some cases, but the patient has about a 30-percent chance of needing glaucoma surgery after a Retisert implant. The Yutiq implant releases fluocinolone at a significantly lower rate, which translates to less risk for the patient; the risk of needing glaucoma surgery at three years is around 5 percent with Yutiq. Of course, the flip side is that it’s not as strong, so patients may continue to need other treatments as well, but hopefully with fewer severe flare-ups of the inflammation.”

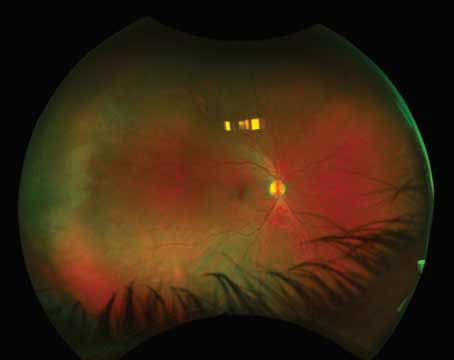

|

|

Chronic birdshot chorioretinitis. Left: Optos color photo showing birdshot spots and vascular sheathing. Right: Fluorescein angiogram showing CME and vasculitis. Shadows of Retisert struts are faintly visible superonasally and inferotemporally. Image courtesy of Pauline T. Merrill, MD. |

Of the implant options, Dr. Janardhana says she’s used Ozurdex the most. “Ozurdex is great for patients who, for various reasons, might not want to start immunosuppressive therapy, or might have contraindications to doing so,” she explains. “In my experience, the benefits of Ozurdex typically last three to six months, depending on the patient. I use it in patients with noninfectious uveitis who otherwise can’t tolerate systemic therapy. I also use it as a bridge medication to help a patient with chronic uveitis who’s starting systemic immunosuppressive therapy, because the systemic immunosuppressive therapy can take months to kick in. The injection helps get them through that initial period.”

Dr. Henry says he also tends to use Ozurdex more often than the other options. “Sub-Tenon’s Kenalog injections usually last a bit longer—six to 12 months,” he notes. “I use this approach if it’s worked for the patient in the past, or if I want a longer duration of action than I get with Ozurdex. Yutiq can last up to two and a half years; I typically reserve it for patients who’ve responded well to several Ozurdex injections. Yutiq may not be as potent as Ozurdex, but it can evoke a longer response without the need for so many injections. Retisert, the surgical implant, can last up to five years. Some doctors also use intravitreal Triesence.”

Retisert, appears to have become less popular with the advent of the newer, nonsurgical options. “For the right patient, Retisert can still be an excellent choice, although I don’t do very many of them,” Dr. Henry notes. “The issues with Retisert are, first, that it can be difficult to get insurance to approve it because it’s so expensive; and second, the patient is virtually guaranteed to end up with a cataract—assuming they haven’t already had cataract surgery—and very likely to develop glaucoma. That means the patient has to be prepared for possibly needing both cataract and glaucoma surgery in the future. So if you go with Retisert, you’re going with what I call the ‘bionic eye’ approach [treatment options that may cause changes inside the eye].”

Clinical Trial Findings

Clinical trial data has shed some light on the comparative risks and benefits of the options. “The POINT study from the MUST clinical trial group compared three current options for treating macular edema due to uveitis,” says Dr. Merrill. “It was a six-month study comparing sub-Tenon’s triamcinolone (Kenalog), intravitreal triamcinolone (Triesence), and an intravitreal dexamethasone implant (Ozurdex). The data suggests that both intravitreal treatments controlled the macular edema faster, but the sub-Tenon’s injection started to catch up by six months.

“The POINT trial found that Ozurdex may have some advantages over periocular or sub-Tenon’s injections in terms of treating uveitic macular edema,” Dr. Henry notes. “I think this data has pushed some uveitis specialists more toward using Ozurdex and perhaps slightly away from peri-ocular steroid injections.”

Dr. Merrill adds that another key finding was that there was less IOP elevation in the sub-Tenon’s group than in the two intravitreal groups. “So, if you’re not worried about your patient’s IOP and you want a fast response, Triesence or Ozurdex are great approaches,” she says. “If you’re more concerned about a pressure increase and have more time, the sub-Tenon’s injection may still be a reasonable option.”

Dr. Merrill says she doesn’t believe implants will ever totally replace simple injections. “There are some situations where you don’t want to do an implant, such as in a patient who is aphakic or has a capsular tear,” she explains. “The implant could end up in the anterior chamber and cause corneal edema. In that case a triamcinolone injection may be preferable. It may be a shorter-term treatment, but you have to weigh the risks and benefits of each option.”

Systemic Steroids

Oral steroids—sometimes with the eventual addition of an immunomodulating drug—are another approach many patients require. Dr. Merrill says that if a patient has a bilateral panuveitis, she’ll usually think about systemic options. “We want something that will treat both eyes,” she explains. “Also, if it’s pretty severe, the treatment will probably be longer-term, making systemic treatment helpful. The initial treatment would be oral steroids, usually 60 mg per day until the eye is quiet, but for no more than a month. After that, I taper down slowly over the following months to 7.5 mg per day or less.

“Meanwhile, as soon as I start the patient on oral steroids, I talk to them about starting a steroid-sparing immunosuppressant such as methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept), or adalimumab (Humira). The idea is to achieve quick control with steroids while starting something that will be better tolerated over the long term.”

In terms of contraindications for oral steroids, Dr. Merrill says you want to carefully consider the systemic side effects. “For instance, if the patient is diabetic, we work closely with the patient’s primary physician to monitor the patient’s blood sugar,” she says. “And, we talk with the patient about all of the systemic side effects that can occur, from short-term mood changes, sleeplessness and weight gain, to longer-term effects ranging from changes in blood pressure to osteoporosis. Fortunately, most people can tolerate steroids in the short term, which is all you should use them for in any case.”

“If the patient has intermediate uveitis, panuveitis or posterior uveitis with retinal involvement—especially if it’s bilateral—I start the patient on oral prednisone,” says Dr. Janardhana. “I typically start with 1 mg per kg, which for most patients ends up being 60 mg. Then I do a taper of about 10 mg per week. If the patient has a relative contraindication to oral prednisone, such as being diabetic or having severe cardiomyopathy, I always correspond with the endocrinologist, cardiologist or primary care doctor prior to starting the patient on oral prednisone to make sure it’s safe.”

Dr. Henry notes that sometimes systemic and local therapy need to be combined. “It depends, among other things, on the anatomic location of the uveitis,” he explains. “If the patient has isolated anterior uveitis, we can typically quiet that down with topical drops and dilation drops. But if someone has a serious intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis or panuveitis, that patient will probably need systemic therapy—corticosteroids, with or without a bridge to longer-term immune suppression—although a few of them can be managed with local steroid injections. Many of those patients will need topical drops, too.”

“Every patient with uveitis is unique,” he adds. “You have to tailor your treatment to their disease and their personal preferences for management. When a patient has chronic, noninfectious severe uveitis, I frequently discuss whether they want to do the systemic therapy approach, or what I call the ‘bionic eye’ approach. In most cases, if someone has autoimmune, bilateral severe disease, I’ll direct them toward systemic therapy. However, some patients are just not interested in systemic therapy; they may choose to undergo chronic steroid injection or local therapy. It’s my job to make sure those patients are aware that they’re at risk for cataract and glaucoma. They may end up with an IOL and a tube shunt, and they have to understand that.”

Antimetabolites

Patients can’t remain on high-dose systemic steroids indefinitely, so if tapering leads to a resumption of the inflammation, surgeons frequently add an antimetabolite or biologic.

“Most patients with chronic, vision-threatening intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis or panuveitis will do best if you get them over to steroid-sparing therapy,” notes Dr. Henry. “In cases where someone has had an ongoing uveitis and the process appears to be a long-term threat to their vision, I’ll typically start with a course of oral steroids first. If it’s severe disease, I’ll prescribe oral prednisone, as high as 60 mg/day, for two weeks. After two weeks I’ll taper by 5 mg per week over an eight-to-10-week period. If it’s chronic disease, I’ll transition to longer-term immune suppression during that time.”

Dr. Janardhana explains that she considers moving to other options when a patient is being weaned off of oral steroid therapy and the disease begins to reactivate. “Typically we can keep a patient on prednisone up to 10 mg/day after tapering,” she notes. “But if the patient needs more than that to keep the eye quiet, we have to try something else. That might mean a series of short-term peri-ocular or intravitreal steroid injections, or a longer-lasting injection such as Ozurdex or Yutiq, or systemic immunosuppressive therapy. The choice of therapy often depends on chronicity, bilaterality, duration, contraindications to medications, and whether there’s an associated systemic disease. I prefer systemic immunosuppressive therapy for patients who have chronic noninfectious uveitis—

especially if it’s bilateral, and of course for those who have an associated systemic disease.

“I typically start the patient on an antimetabolite, either methotrexate (dose ranges from 7.5 to 25 mg, oral, intramuscular or subcutaneously, weekly) or mycophenolate mofetil, a.k.a. CellCept (dose range 750 to 1,500 mg by mouth twice a day),” Dr. Janardhana continues. Common side effects of methotrexate are nausea, vomiting and fatigue; more severe side effects include liver toxicity, cytopenia and even kidney dysfunction in high doses. Hence, methotrexate isn’t a good choice for patients who drink alcohol, because liver toxicity can occur. Methotrexate might be OK for patients who only drink alcohol once in a while, but if they drink alcohol more than a few times a month I give them mycophenolate mofetil. CellCept can cause similar side effects, but it’s less likely to cause liver toxicity, so it’s OK to use in patients who drink alcohol. Also, it’s important to give folate with methotrexate to minimize any gastrointestinal side effects. And, it’s important to let patients know that with time, side effects such as nausea, vomiting and fatigue should decrease.

| Coming Soon? A Suprachoroidal Steroid injection Another approach to getting a steroid into the eye is injecting it into the suprachoroidal space. Surgeons note that this has some potential advantages over the other options. “The basic science data suggests that the steroid concentrates in the suprachoroidal space and the adjacent retina and choroid, with very little getting into the anterior chamber or angle,” explains Christopher R. Henry, MD, a fellowship-trained vitreoretinal surgeon and uveitis specialist who practices at Retina Consultants of Texas. That’s a theoretical advantage over intravitreal or periocular steroids, because we may be able to get a robust therapeutic response with a lower risk of cataract and glaucoma. The jury is still out, but the clinical trial data has been very promising, in terms of improving vision, reducing macular edema and limiting ocular side effects.” Dr. Henry says his practice participated in the PEACHTREE, MAGNOLIA and AZALEA clinical trials. “The new technique for performing suprachoroidal injections is fun,” he notes. “These injections are not as difficult to perform as they may sound. The technique is quite intuitive, and the patients I had in the open-label AZALEA trial did extremely well.” Pauline T. Merrill, MD, a partner at Illinois Retina Associates and an associate professor of ophthalmology at Rush University in Chicago, says she hopes that suprachoroidal injection of a steroid will be approved soon. “The studies of that approach found rapid control of macular edema with possibly fewer IOP concerns than we have with intravitreal injections,” she notes. —CK |

“Both of these medications take three to six months to work,” she adds. “For that reason, I either have the patient on topical steroid drops, give a steroid injection or prescribe oral prednisone to serve as a bridge until the antimetabolite takes full therapeutic effect.”

Dr. Merrill points out that one of the holy grails for treating uveitis would be a nonsteroidal injectable medication. “The hope is that we could control inflammation without so much concern about steroid-response glaucoma,” she notes. “We currently sometimes use intravitreal methotrexate off-label; that’s being looked at in the MERIT study of the MUST trial group, which is comparing Ozurdex, methotrexate and Lucentis for uveitic macular edema in otherwise quiet eyes.”

Biologics

“Some patients with severe noninfectious uveitis won’t respond sufficiently to antimetabolites,” Dr. Janardhana points out. “If patients are failing despite the optimal dosage of antimetabolites, then I go to the next step: TNF inhibitors—biologics. The biologics include adalimumab (Humira) and infliximab (Remicade), which is an infusion. Adalimumab is a 40-mg subcutaneous injection given every other week, and patients can self-inject it at home, which is very convenient. It typically works well for my patients, so if the patient is failing antimetabolites, starting a medication like Humira would be my next step.”

“Antimetabolites such as methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept) are still very much in use,” notes Dr. Merrill. “They tend to be the less-expensive systemic medications—especially methotrexate. The T-cell inhibitors, cyclosporine and tacrolimus, are still around, as are the alkylating agents. [See below.] However, I use the cytotoxics much less now that we have options like the biologics, especially Humira. Humira is FDA-approved for uveitis, so that’s been a huge advance.”

Dr. Henry says he starts the majority of patients needing immune suppression on an antimetabolite or a biologic. “Whether I opt for an antimetabolite or a biologic depends in part on the severity of the disease and how aggressive it is, and partly on the specific diagnosis,” he notes. “For a less-aggressive, chronic, but still vision-threatening uveitis I’ll sometimes lean towards methotrexate or mycophenolate first. Some patients do very well on this regimen. But if inflammation persists despite a sufficient course of one of these, then I’ll add a biologic such as adalimumab.”

Dr. Janardhana notes that some uveitis patients may end up on both antimetabolites and biologics. “If the patient is already on an antimetabolite like methotrexate or CellCept, I usually keep them on a low dose of the antimetabolite and add the adalimumab to that,” she explains. “The justification for this has been to prevent antibodies against the adalimumab from forming. However, it’s becoming less clear how much the immune system really does form antibodies in this situation, so if patients do well on adalimumab, I may taper them off the antimetabolite.”

She adds that even adalimumab may not be sufficient to improve the uveitis in some patients. “Some patients don’t respond sufficiently to it, while others are stable on it for years and then it stops working,” she notes. “If that happens, my next step is to switch within this class of drugs to infliximab (Remicade), which is an infusion.”

Dr. Henry agrees that patients with the most aggressive and vision-threatening processes may need biologic infusions. “Biologic infusions would include infliximab or golimumab (Simponi Aria), which can work well for certain patients,” he says. “These are typically given in a rheumatologist’s office. If a patient has extremely severe disease such as lupus-associated occlusive retinal vasculitis or ANCA-related disease, I usually favor aggressive treatment with rituximab.”

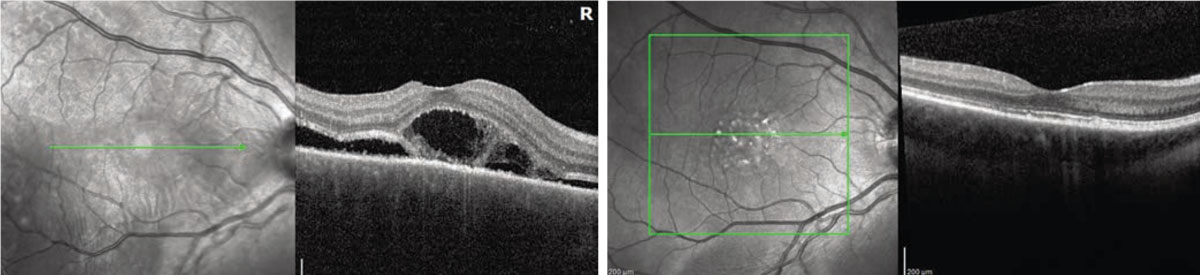

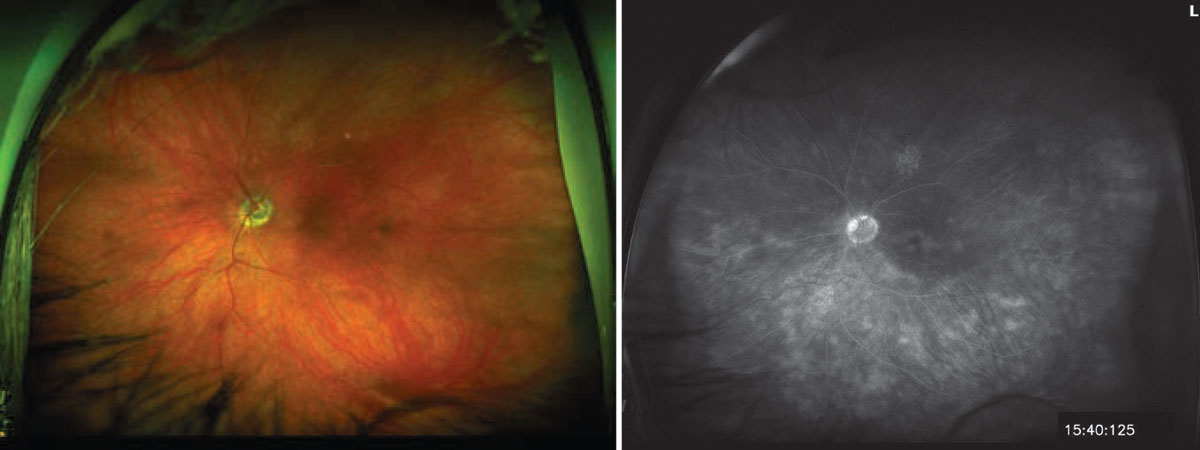

|

| Fluorescein angiograms of a 56-year-old female diagnosed with birdshot retinochoroiditis. Left: Before treatment. She was treated with adalimumab and mycophenolate mofetil, with Ozurdex implant supplementation as needed. Right: After two years of treatment. Image courtesy of Christopher R. Henry, MD. |

“Of note, socioeconomic factors also sometimes play a role in picking an appropriate treatment plan,” Dr. Janardhana says. “It’s important for patients to remain compliant with appointments and for us to monitor labs and symptoms frequently while on these medications. I typically monitor patients’ labs every three months—in particular white cell count and liver and kidney function tests. Also, before starting any of these immunosuppressive labs, it’s important to check patients’ white cell count and kidney and liver function tests, as well as ruling out infections such as tuberculosis, syphilis and hepatitis. In particular, it’s important to rule out tuberculosis prior to starting TNF inhibitors.”

Other Options

Of course, some patients may fail even on those options. “In that case there are other medications we can try, including CD-20+ B cell monoclonal antibody inhibitors, like rituximab,” says Dr. Janardhana. “This is used in severe refractory noninfectious uveitis and scleritis.”

Other options include:

• IL-6 antibodies. “Tocilizumab (Actemra) is relatively new,” says Dr. Henry. “It’s FDA-approved for treating giant cell arteritis. In those patients it’s helped to minimize the long-term side effects of oral steroids, but it also works very well for patients with uveitis. I’ve had good luck using it in patients with refractory scleritis, and I’ve switched some more aggressive uveitis patients who were on antimetabolites or a biologic such as adalimumab to tocilizumab. They’ve done well. For example, I have one patient with aggressive Blau-syndrome-related uveitis who’s done very well since switching to tocilizumab. So I’m a big fan. I think it has a lot of promise.”

“Many initial studies are looking at tocilizumab for treating non-infectious uveitis and the data looks promising,” agrees Dr. Janardhana. “I’ve seen patients respond very well to it. In fact, my patients who are on this medication usually also have systemic disease, and it’s worked well to control both.

“I think the lack of extensive data is the reason tocilizumab is still not a ‘go to’ medication,” she adds. “The other medications, like the antimetabolites and biologics, have been well-studied for both uveitis and rheumatology, so we lean more towards those when choosing our treatments. But if the data continues to be promising, I think more doctors will start using drugs like tocilizumab to treat uveitis.”

Dr. Merrill says other studies looking at intravitreal sirolimus and an intravitreal IL-6 inhibitor are currently under way. “One arm of the DOVETAIL study is looking at an IL-6 inhibitor for uveitic macular edema,” she says. “Then there’s the ongoing LUMINA study of intravitreal sirolimus from Santen. The previous studies of intravitreal sirolimus were promising; hopefully LUMINA will provide the data needed for FDA approval. And, in the not-too-distant future, we may have even more sustainable treatment options. A number of companies are investigating new methods of drug delivery, as well as approaches using gene therapy.”

• T-cell inhibitors. Dr. Henry says he almost never recommends a T-cell inhibitor like cyclosporine or tacrolimus anymore. “I have a few patients with birdshot chorioretinopathy who are on cyclosporine, and some patients who’ve had organ transplants who are taking tacrolimus,” he says. “But I almost never recommend them, because they require careful monitoring of factors such as blood pressure, and there are issues concerning tolerability. On the other hand, biologics work very well and are well-tolerated. So I typically go to a biologic before considering a T-cell inhibitor.”

Dr. Janardhana agrees. “I tend to shy away from T-cell inhibitors/calcineurin inhibitors such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus, and alkylating agents such as cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil,” she says, “given the severe side effect profile of these medications.”

• Alkylating agents. Dr. Henry also says he very rarely uses alkylating agents. “They’re very toxic,” he points out. “For the majority of patients, biologics can do the job. For me to consider using an alkylating agent, a patient would have to have extremely aggressive, refractory disease.”

Dr. Janardhana notes that studies of other options are ongoing. “Studies are being conducted for the treatment of noninfectious uveitis using other biologics such as golimumab and secukinumab (Cosentyx, an IL-17 inhibitor),” she says, “as well as T-cell inhibitors such as abatacept (Orencia). Ophthalmologists might see these medications being used for other systemic diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease or rheumatological disorders.

“We’re still awaiting studies to see how efficacious these medications are against noninfectious uveitis,” she says, “but if patients are already on these medications for systemic disease and have a history of uveitis, I don’t immediately change medications, unless the patient has a recurrent uveitis flare or persistent chronic uveitis.”

Managing Patient Expectations

Of course, no matter how effective your treatment may be, patient expectations are a huge factor in how the patient will perceive your efforts over the long run.

Dr. Janardhana says that she tells her new uveitis patients that uveitis is a complex disease with no quick remedy. “I explain that uveitis is kind of a blanket term,” she says. “It can be caused by autoimmune diseases or an infection, and we can’t identify the cause in half of the uveitis cases we see. In addition, uveitis—especially noninfectious uveitis—is often a chronic disease, and every patient is different. Some medications work for one patient but not the next, and we don’t know why.

“The progress of uveitis is also somewhat unpredictable,” she continues. “We don’t always know why one person’s disease is more aggressive than another’s. Sometimes chronic uveitis will be quiet for years, and suddenly it becomes active, for reasons we can’t determine. We do believe that factors like stress, illness and even traveling can act as triggers to reactivate the disease and cause a flare-up, but there’s no way to predict exactly what’s going to happen, or when.

“Most of all, patients need to understand that treating uveitis is a long process,” she concludes. “We have to try different medications in a stepwise approach, and it can take several months just to find the right medication to get their disease to quiet down. So, this is a marathon, not a sprint. But no matter what it takes, I make sure they know that I’m there to work with them and help them get better.”