Uveitic glaucoma is a diverse disease. Patients with advanced disease may present with open or closed angles—the latter sometimes acute, sometimes chronic. Acute angle closure obviously requires an urgent response, but for me, chronic angle closure is more a predictor of the chronicity of the problem, rather than something to manage differently from open angle glaucoma.

When managing an advanced uveitic glaucoma patient, the job of the glaucoma specialist is twofold. First, in the short term you need to relieve any existing angle closure. Second, you need to take intraocular pressure out of the equation so that elevated IOP doesn’t restrict the management of chronic inflammation.

In terms of removing IOP from the equation, I believe it’s crucial to understand that you shouldn’t reduce steroid treatment just to accomplish this. That’s a false economy. The patient should be able to use whatever treatment is needed to address the uveitis, as determined by the patient’s uveitis specialist. For that reason, an advanced uveitic glaucoma patient often needs to undergo glaucoma surgery such as trabeculectomy or have a tube shunt implanted. We won’t be successful in every case, but a glaucoma surgeon who does trabs and tubes on a regular basis will be very adept at managing this.

|

| One type of angle closure seen in some advanced uveitic glaucoma patients is chronic angle closure associated with peripheral anterior synechiae. This can be interpreted as a marker of chronicity; the elevated IOP is more than just a steroid response, and this patient is likely to need surgery. |

The Importance of Surgery

Performing a less-invasive procedure, such as a MIGS surgery, may seem like an attractive option—perhaps performing a Kahook Dual Blade goniotomy or an iStent, on the basis that these may be enough to avoid more invasive operations. However, these procedures aren't intended to treat severe disease. In advanced uveitic glaucoma patients, a MIGS procedure is unlikely to resolve the problem; it simply kicks the can down the road. That’s a real concern, because in advanced glaucoma, there’s an opportunity cost for doing this: You’re leaving the patient exposed to further vision deterioration over the long term.

The reality is, when managing an advanced uveitic glaucoma patient, the glaucoma specialist’s job is to take pressure out of the equation as much as is possible. In advanced cases, that requires a trabeculectomy or a tube implant. If your patient has advanced angle closure and/or advanced optic disc and visual field damage, you probably have only one opportunity to fix it. By the time you get to the next opportunity, it’s too late—the glaucoma has progressed further. The patient with a paracentral defect has lost central vision, and a patient with an advanced central defect is really in trouble. That’s why you need to achieve definitive control as quickly as possible.

I think it’s important to get away from the idea that glaucoma surgery is something that doesn’t last forever—the idea that you’ll try one thing and then another until the patient reaches the target pressure. Baerveldt implants and trabeculectomies last a very long time, and they give you the opportunity to achieve definitive control from early on.

The glaucoma specialist in this situation must have a range of glaucoma surgeries at his or her disposal. Doctors who say, “I only do this procedure or that procedure” aren't offering what many of their patients need. That may sound a bit harsh, but it’s reality.

Managing Angle Closure

|

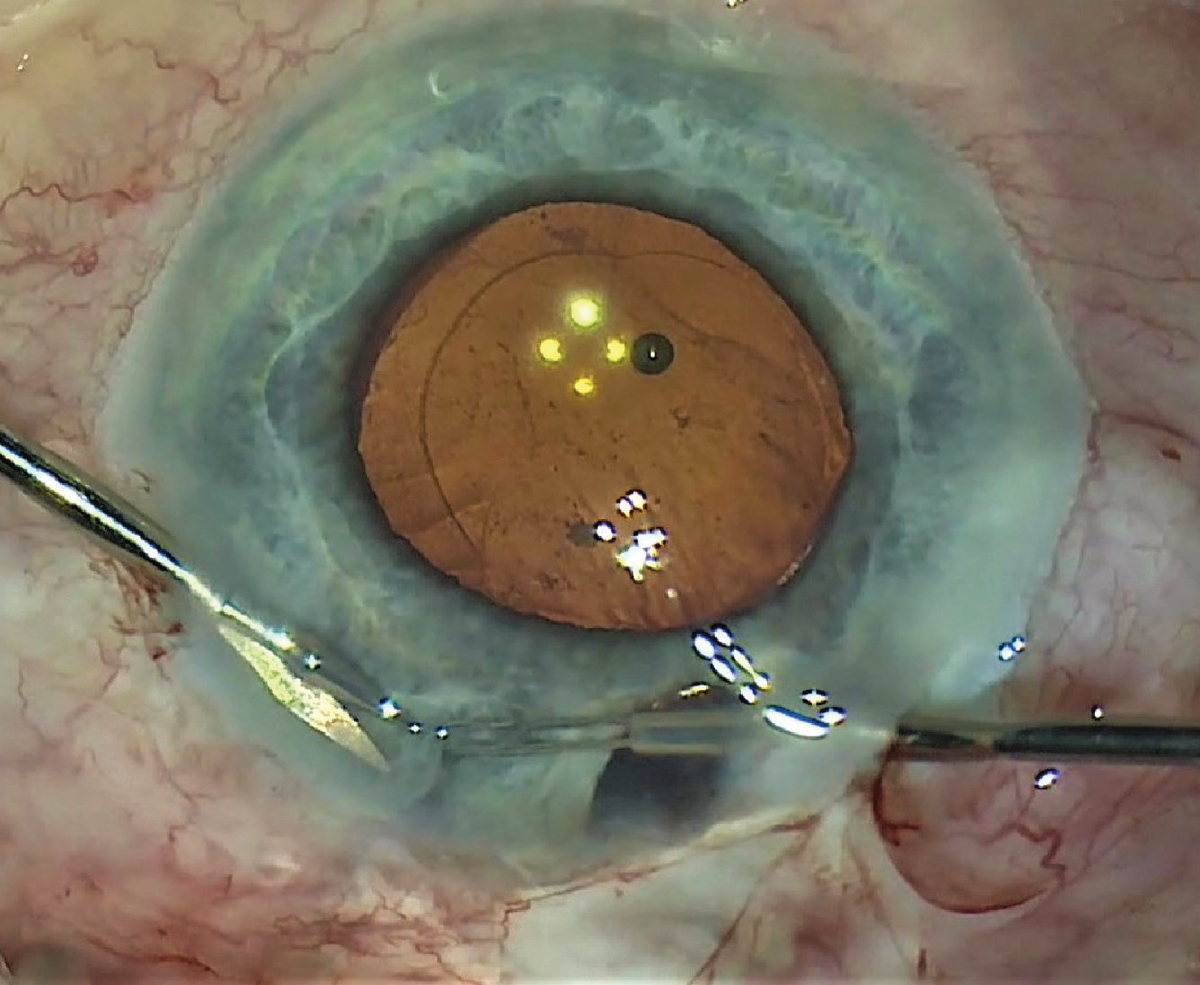

| When encountering a uveitic patient with angle closure, the surgeon may be tempted to perform a laser peripheral iridotomy. That doesn't work well in these patients, because the sticky aqueous prevents the iris from falling back, and the angle doesn't open. Performing a surgical iridectomy (as shown above) is far more effective. |

If you have an open angle that’s completely clean and pigment free, you may be tempted to believe that the patient’s pressure rise is caused by steroid responsiveness rather than by the uveitis. However, if you find a lot of synechiae in the angle, you know the angle has been severely compromised. And if you find a lot of synechiae and the pressure is episodic—sometimes high and then normal again—you know that the situation probably will not settle down. That means the patient is more likely to need surgery in the long term.

Acute angle closure in uveitics is something that’s particularly troublesome to me. It’s not that common, but it’s very severe and we often fail to treat it effectively. There are three types of angle closure in uveitis: pupil block; chronic synechial angle closure; and forward movement of the lens-iris diaphragm.

The first type of angle closure, pupil block, is the biggest management challenge. It may relate to a pre-existing narrow angle or coincidental angle closure; relative pupil block from fibrin obstructing the pupil; or absolute pupil block caused by posterior synechiae. We’re all familiar with primary angle closure, which is due to relative pupil block, but in uveitis, the pupil block is absolute, which is very different. Because the iris is ballooning against the cornea, this isn't just a closed angle occluding the trabecular meshwork; this is an angle that’s completely zipped shut with sticky aqueous and iris, right up against the cornea.

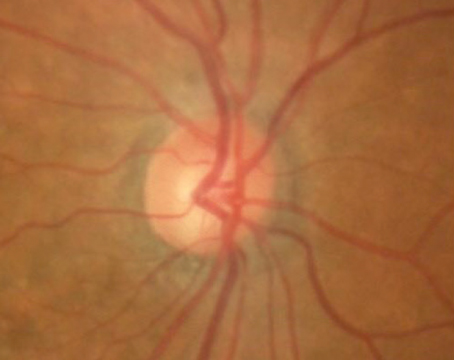

The second type of angle closure in uveitis is chronic angle closure, associated with peripheral anterior synechiae, secondary to inflammation (e.g., nodules in the angle, neovascularization, and/or a cyclitic membrane). (See example, first image above) For me, chronic anterior synechiae in the angle is primarily a marker of chronicity; it tells me that there’s more than just a steroid response going on here. The patient doesn’t have high pressure just because of one acute attack—a problem has existed for a long time. As noted earlier, this patient is more likely to need surgery in the long term.

There’s a popular idea that this problem may be relieved by goniosynechialysis. Actually, goniosynechialysis doesn’t work very well in these patients. For example, a retrospective study conducted in Singapore reviewed the outcomes of goniotomy procedures performed in 31 eyes with glaucoma secondary to anterior uveitis.1 It found that the eyes that achieved success (defined as an IOP of less than 21 mmHg) had a mean of 0.5 clock hours of peripheral anterior synechiae; the eyes that failed to achieve success had a mean of 2.5 hours of PAS.

In general, there’s very limited data regarding using goniosynechialysis to address this, and certainly no comparative studies showing that it works in the long term. I’m not a fan; this procedure causes a lot of bleeding, and I’m not convinced it does anything helpful.

The third type of angle closure seen in these patients is a classic symptom of uveitis: forward movement of the lens-iris diaphragm, leading to central anterior chamber shallowing. In the past, a shallow central anterior chamber was often misdiagnosed as pupil block, but nowadays, most doctors don’t jump to that conclusion.

When you find a very shallow central chamber, it either means the crystalline lens is very large, or something is pushing the lens forward. Classically, in uveitis, this could be caused by posterior scleritis or Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. However, in clinical practice you almost never see it associated with these causes. The vast majority of cases I see are the result of vitrectomy for retinal detachment that was done using too much gas; a large, cataractous lens; or, most commonly, the result of aqueous misdirection following previous ocular surgery. (The latter can be addressed via atropine or steroids, or a pars plana vitrectomy if it’s recalcitrant.) So, even though posterior scleritis and VKH have been associated with this, much of the time, the cause is iatrogenic.

The Iridotomy Dilemma

One problem with addressing angle closure in a patient with uveitic glaucoma is that most surgeons don’t encounter it very often. So, when they do encounter it, they tend to opt for the treatment that might work well in other situations: laser peripheral iridotomy.

That’s not a good approach in this situation, for a couple of reasons. First, if you perform laser iridotomy, you’re lasering the corneal endothelium. Second, because these eyes are very inflamed, the aqueous is kind of sticky; as a result, the iris often doesn’t fall back following the LPI and the angle doesn’t open. You end up with a patent iridotomy and a closed angle, even though you’ve relieved the iris bombé. For example, one patient I encountered had undergone three LPIs. The LPIs opened up the iris, and the bombé has fallen back; nevertheless, the iris was still completely zipped shut against the cornea, and the angles remain closed.

Not surprisingly, this ineffective treatment comes with an opportunity cost. I’ve seen patients like this in their 40s who only received an LPI and now have no light perception, just because they weren’t adequately treated.

|

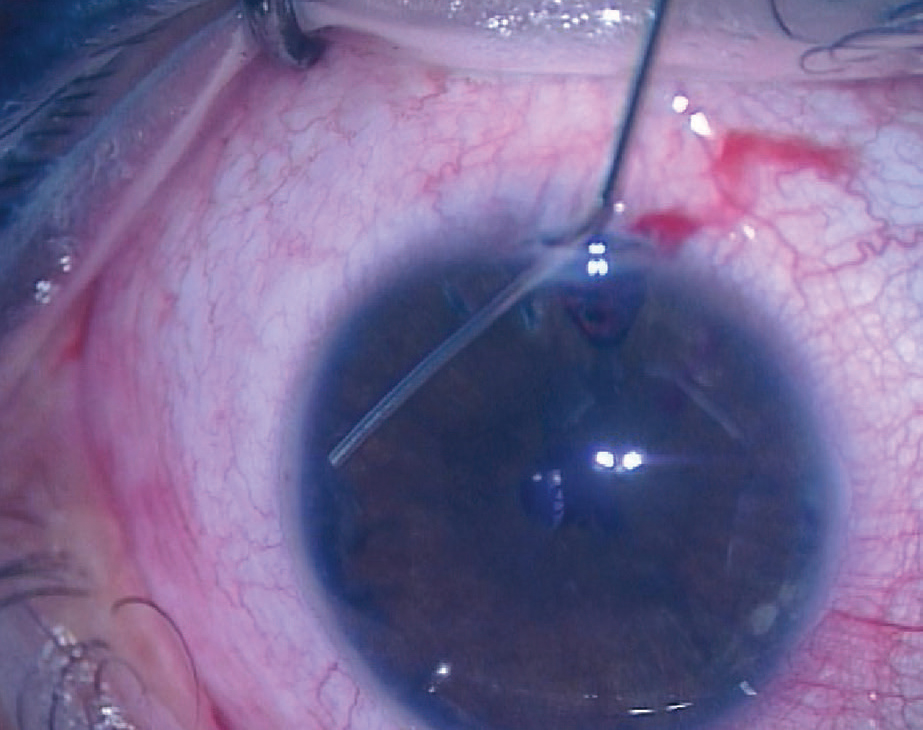

| Having performed a surgical iridectomy allows the surgeon to open the angle with viscoelastic. Once the angle has been physically opened, the fact that you’ve relieved the iris bombé should keep it from closing back up. |

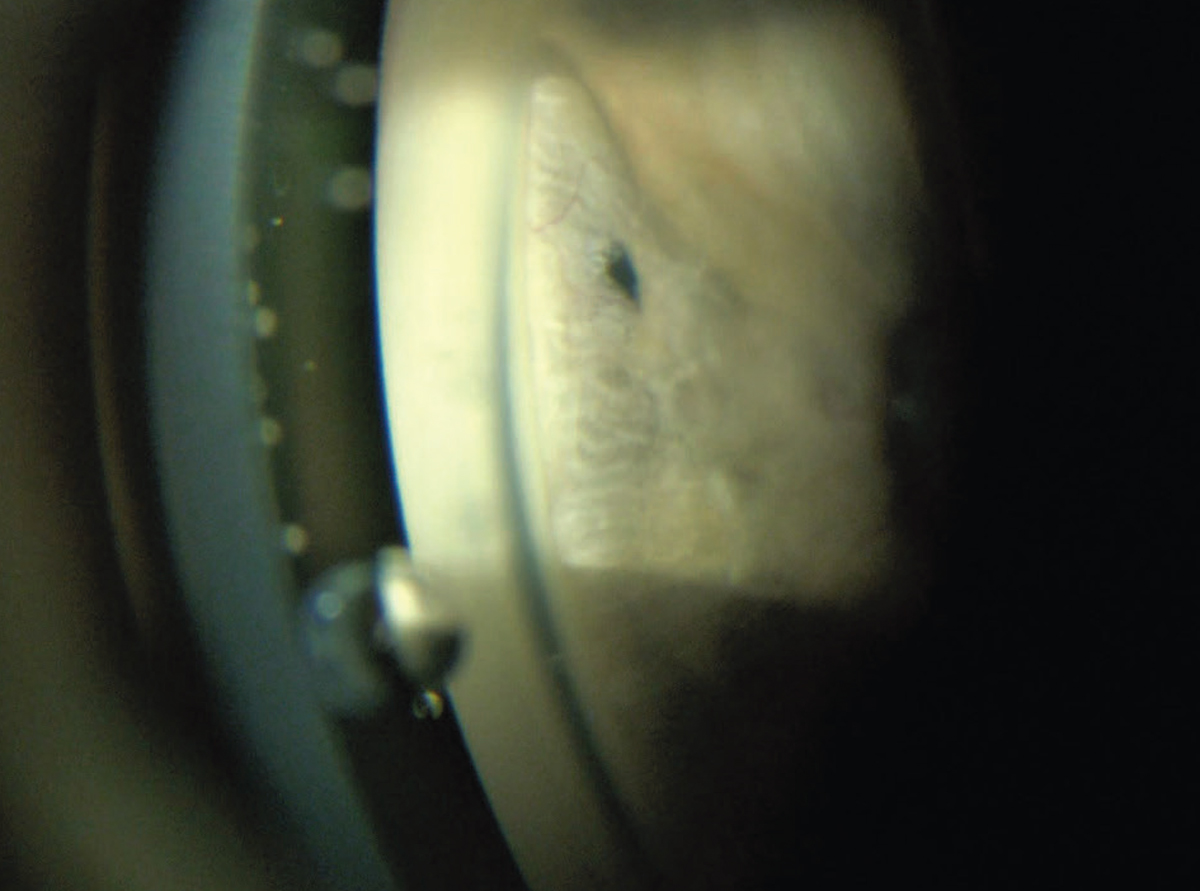

The answer is straightforward: Surgical iridectomy is much more definitive than an LPI.2,3 (I prefer to do such an iridectomy using vitrectomy forceps and scissors, which provide good visualization.) (See example, second image above) Doing this doesn’t just make a bigger hole; once you’ve made the hole, it also allows you to physically open up the angle using a viscoelastic such as Healon GV. (See example, above.) In theory, you could do this through an LPI opening, but it has to be done in the operating room, so it makes better sense to create the opening surgically. Once the angle has been physically opened, the fact that you’ve relieved the iris bombé should keep it from closing back up.

Another reason to create the hole surgically is that laser-created holes often close up in uveitic patients. Surgical ones are bigger, so they don’t close up as often. Yes, it’s possible that an LPI will remain open, and sometimes a surgical iridotomy will close, despite being larger than an LPI. But being in the OR to perform the surgical iridotomy also allows you to use viscoelastic to physically open the closed angle, which truly resolves the problem. Just making the hole may not resolve it.

Note that this process isn't the same as goniosynechialysis. This isn't about breaking physical adhesions. Goniosynechialysis is increasingly popular, but the evidence suggests that it’s not particularly effective in this type of situation.

Tubes vs. Trabs

Trabeculectomy has a bad reputation in uveitic glaucoma, while tube shunts have a good reputation. Generally, I’m known as an advocate of tubes for glaucoma surgery, but I tend to do trabeculectomies in uveitics—especially in advanced cases, as long as the patient has no risk factors for failure other than the uveitis itself. For example, if the patient is phakic and hasn’t had any previous ocular surgery, he or she may be a good candidate. In these patients, trabeculectomies generally work well.

One issue here is that both high and low intraocular pressures tend to be more extreme in uveitic glaucoma patients than in POAG patients. The explanation may be that chronic uveitics have a little bit less aqueous than POAG patients—with even less outflow. This leads to a very wide spread of pressures. As a result, you can end up with a trabeculectomy where you have very little drainage, but the pressure is very low indeed.

Our trabeculectomy success rate with these patients has been good. In a study we conducted 15 years ago, mean success, defined as IOP ≤21 mmHg, was about 80 percent at about four years. (Of course, less than 21 mmHg is a fairly low bar these days; in cases of advanced uveitic glaucoma, you really want to be getting the pressure down to 10 mmHg or thereabouts.) The reality is, if you have a uveitic patient with good control of inflammation and no other risk factors for failure, a trabeculectomy is probably the best way of getting down to the single digits.

Note: If you’re performing a trabeculectomy in a patient like this, you have to use releasable sutures, and you have to be prepared to use more sutures than you would normally use. You should expect to release them selectively later (or use laser suture lysis). I’ve always used mitomycin-C in this situation.

Of course, there are certain uveitics who shouldn't have a trabeculectomy, including cases of uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, those with severe uveitis from early childhood, and those with any other risk factor for failure. Ethnicity is a possible risk; in my experience, Black patients in this situation have a lower success rate. We’ve also found that pseudophakes fail more often, for reasons we have yet to determine. (In fact, pseudophakia is the only major risk factor we’ve identified.)

In some patients with mild disease, an alternative to trabeculectomy such as the Xen gel stent or PreserFlo microshunt (from Santen) may be a workable alternative. If the uveitic patient has high IOP, mild glaucoma, no trabeculectomy failure risk factors and a relatively healthy disc, I’ll use a Xen implant with mitomycin-C, or an InnFocus Microshunt with mitomycin-C. If the same patient had more advanced glaucoma with significant optic neuropathy, I’d perform a trabeculectomy with MMC. (I don’t do canal-based MIGS in these patients.)

Our group published a report about a series of uveitic patients who received Xens; those patients did pretty well.4 I’ve subsequently written up a series of these patients treated with PreserFlo which hasn’t been published yet, although we presented the data at the American Glaucoma Society meeting in Washington, D.C., two years ago. One significant difference between these two studies was the composition of the subject pools. The XEN study participants were mostly young Caucasian individuals, who tended to have healthy conjunctiva (at least partly because of their age and limited exposure to glaucoma drops). The subjects in the PreserFlo study were mostly not Caucasian. That made a difference, because we were able to detect an association between ethnicity and outcome in the PreserFlo study; we weren’t able to test for that in the other study.

|

| This patient's angle remained closed despite a patent LPI. |

Given that tube shunts generally work well in uveitic patients, why even consider performing a trabeculectomy? Because in general, trabs get lower pressures, and patients with advanced uveitic glaucoma need a really low pressure. I realize that most surgeons faced with a uveitic glaucoma patient would just implant a tube. But I was doing trabs in uveitic patients many years ago when tube shunts were much less popular. Because my success rate in uveitics with this approach had a good success rate, I never stopped.

Today, of course, my practice does place a lot of tube shunts in our uveitic patients, simply because there’s almost always some kind of risk factor for failure. For example, some of our patients here in London are African, and they scar more easily post-surgery. In those patients, Xens and Microshunts don’t work so well; trabs don’t work so well; even tubes don’t work so well. But tubes seem to work better than the other options, so we have a lower threshold for using tubes. In addition, if a uveitic patient has a single-chamber eye, neovascular glaucoma or juvenile idiopathic arthritis, I just go straight to a tube.

Which Tube?

If you’re choosing to implant a tube shunt in a patient with uveitic glaucoma, the next question is, which shunt is most likely to work well? In most cases we opt for either a Baerveldt 350 or a Paul Glaucoma Implant in patients with advanced disease.

Many surgeons are reluctant to implant a Baerveldt 350 in a uveitic glaucoma patient with advanced disease, but if you’re trying to get lower pressures, the evidence is very much in favor of the Baerveldt.5 My experience supports this as well. The Baerveldt 101-350 gives the best pressure control in the long term for many uveitics, and, more recently, the Paul Glaucoma Implant seems to produce similar pressures.

At the same time, there are certain patients in whom we shouldn’t use the Baerveldt 350. For example, I wouldn’t place a 350 in a patient who comes to see me at age 20, who’s had severe uveitis since the age of three. These patients have low aqueous production, and they’ll go from very high pressures to very low pressures very easily. I’d also avoid placing a Baerveldt 350 in a uveitic patient with significant neovascularization, and patients who’ve had multiple cyclophotocoagulation treatments. (I would never use CPC in one of these patients myself, because the ciliary body is already diseased.)

People often say that a Baerveldt 350 is too much for a uveitic patient. In most cases, it’s not—although it’s definitely too much for some uveitics. So, you need to choose the patient carefully. If I think the 350 will be too much, I move to the smaller plates.

In very sick eyes, I tend to use a single-plate Molteno. Studies have shown that the Molteno implant does well in these patients.6 This raises a few eyebrows among the nurses at Moorfields, because today, surgeons rarely use a Molteno. But when I see somebody with severe juvenile idiopathic arthritis, who’s had the disease since early childhood, I prefer to put in a Molteno. (Admittedly, as treatments for uveitis get better and better, I’m seeing fewer of those very sick eyes.)

Doing the Right Thing

Unfortunately, today there are many places where surgeons are avoiding doing trabs and tubes. A patient going to a major center in a major city will probably get the right type of surgery done, but for many of today’s ophthalmologists, this kind of surgery has become alien. They don’t do it on a regular basis. That’s a problem.

If you’re unable to offer a patient with advanced uveitic disease and glaucoma a tube or trabeculectomy, you should refer the patient. The problem is, if you’re a glaucoma specialist and you’re referring glaucoma cases to somebody else, what does that make you? You’re not offering a full range of procedures. Yes, the new procedures are elegant; patients like that and doctors like that. But when you’ve got a disease like advanced uveitic glaucoma to treat, those procedures may not suffice to save the patient’s vision.

This article has no commercial sponsorship.

Dr. Singh is a professor of ophthalmology and chief of the Glaucoma Division at Stanford University School of Medicine. Dr. Netland is Vernah Scott Moyston Professor and Chair at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Dr. Barton is a professor of ophthalmology at University College London and former director of the glaucoma service at Moorfields Eye Hospital. He has consulted for Alcon, Allergan, Ivantis, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Santen Pharmaceuticals, Glaukos, iStar, Laboratories Thea, Advanced Ophthalmic Innovations, Elios and Shifamed.

1. Ho CL, Walton DS. Goniosurgery for glaucoma secondary to chronic anterior uveitis: Prognostic factors and surgical technique. J Glaucoma 2004;13:6:445-9.

2. Betts TD, Sims JL, Bennett SL, Niederer RL. Outcome of peripheral iridotomy in subjects with uveitis. Br J Ophthalmol 2020;104:1.

3. Holland GN, Barton K. Iridotomies in eyes with uveitis: Indications and techniques. Br J Ophthalmol 2020;104:1.

4. Sng CC, Wang J, Hau S, Htoon HM, Barton K. XEN-45 collagen implant for the treatment of uveitic glaucoma. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2018;46:4:339-345.

5. Ceballos EM, Parrish RK 2nd, Schiffman JC. Outcome of Baerveldt glaucoma drainage implants for the treatment of uveitic glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2002;109:12:2256-60.

6. Molteno AC, Sayawat N, Herbison P. Otago glaucoma surgery outcome study: Long-term results of uveitis with secondary glaucoma drained by Molteno implants. Ophthalmology 2001;108:3:605-13.