When performing cataract surgery on an average patient, we know there’s a 99.9-percent chance everything will go beautifully. However, that’s not the case when a patient has pseudoexfoliation; in that situation there’s a good chance you’ll encounter problems. You’re likely to be dealing with a s

|

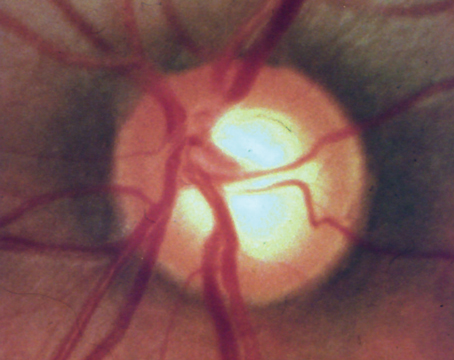

| Two classic signs of pseudoexfoliation. Left: Pseudoexfoliation material on the cataractous lens. Right: A small pupil with signs of roughness and whitish deposits. |

mall pupil, and you may have issues creating the capsulorhexis or rotating the nucleus. The zonules are weak, making late postoperative subluxation of the lens a real possibility.

For these reasons, if you know your patient has pseudoexfoliation you should come to the table with a backup plan. How will you deal with complications if they occur? And what can you do to minimize the likelihood of late subluxation?

Hiding in Plain Sight

Because our practice is a referral center, we see more pseudoexfoliation than many surgeons do. (Some surgeons only encounter one or two cases a year; I perform cataract surgery on one or two pseudoexfoliation patients every week.) For that reason, our surgeons are in a good position to work on this issue. We’re always trying to find ways to minimize late subluxation in these patients.

One factor that complicates the prevention of late subluxation is that surgeons often fail to identify the presence of pseudoexfoliation, even during the surgery. In about 70 percent of the cases in one reported series of subluxed lenses—many of which were in bags containing cap-sular tension rings—the surgeon’s notes stated that the eye had no pseudoexfoliation.1 The removed lenses, however, proved

|

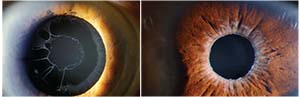

| What the surgeon may see when there’s late subluxation of the lens. The zonules are not functional, so the lens drops. |

them wrong. Although the pseudoexfoliation wasn’t clinically obvious, the pseudo-exfoliation material could be seen in the capsular bag afterwards.

This suggests at least three things:

1. It’s easy to miss the presence of pseudoexfoliation.

2. A capsular tension ring doesn’t prevent late subluxation (although it does make the lens easier to center, easier to refixate, and easier to retrieve if it falls back).

3. If you encounter a late subluxation, the odds are good that it was caused by the presence of pseudo-exfoliation.

Helpful Strategies

Admittedly, it’s difficult to deter-mine how much a given preventive strategy will impact late subluxation, because subluxation u

|

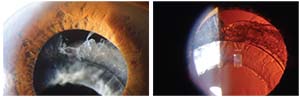

| A Cionni ring inside a capsular bag. Capsular tension rings may help to center the lens and make the capsule easier to grab in cases of late subluxation, but they don’t appear to prevent phimosis or late subluxation. |

sually doesn’t happen until eight to nine years after uncomplicated surgery. Nevertheless, when performing surgery on a glaucoma patient, we should treat every eye as if it has pseudoexfoliation and may develop late subluxation. That means several things:

• Assume that pseudoexfoliation may be present and operate care-fully. Do every cataract surgery on a glaucoma patient elegantly, as-suming that pseudoexfoliation may be a problem. Don’t do a rush job; that will increase the likelihood of complications and late subluxation. As noted earlier, histology has shown that surgeons often fail to see signs of pseudoexfoliation even when it’s present. That’s why it pays to simply assume it may be there.

• Don’t work through a small pupil. A small pupil, one of the hall-marks of pseudoexfoliation, is one of the main warning signs—if not the main warning sign—of potential in-traoperative complications. In past years we taught courses on how to do phaco working through a 3-mm pupil. It is possible to do that, but in retrospect it was a mistake for us to be teaching that; it probably hastened some of the subluxations we’re seeing today, 10 or 15 years later. Doing the phaco through a small pupil was simp-ly too hard on the eye.

Today, we have a range of tools that can be used to widen a small pupil, so leaving it small is unnecessary. One simple approach that may suffice in some cases is injecting a cohesive viscoelastic to move the iris (after injecting a dispersive viscoelastic to protect the cornea). Sometimes that’s enough to enlarge the pupil, avoiding the need to use mechanical means to widen it.

In terms of mechanical options for enlarging the pupil, we used to just manually spread it with a handheld tool, more or less tearing or cutting the iris. Today, we have many options for widening the pupil: We can use iris hooks; the Malyugan ring; the APX System; or devices from Morcher, Graether or Perfect Pupil. All of these tools widen the pupil and thereby decrease the complication rate from cataract surgery. It may take you an extra 30 seconds to do this, but doing surgery through a small pupil is unnecessary and may well backfire.

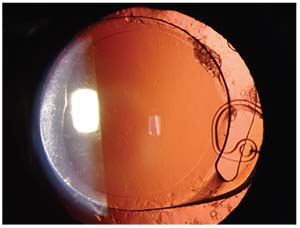

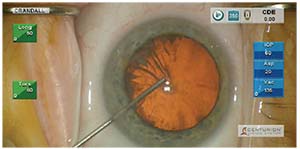

• Be alert for wrinkling of the anterior capsule. It’s not always possible to be aware of zonular weakness ahead of time, but one sign that should alert you to this problem during surgery is wrinkling of the capsule when you touch it at the start of capsulorhexis. (See image, next page.) That should put you on guard that you’re dealing with a weakened zonule.

• Don’t create a small ‘rhexis. If you try to rotate the lens working through a small ‘rhexis, you can cause zonular damage.

• Use a capsular tension ring if necessary, but don’t expect it to prevent late subluxation. Placing a capsular tension ring can definitely help to center the lens. It may also help to make the lens easier to deal with in cases of late subluxation, because the ring makes the capsule and its contents easier to grab onto. (Many surgeons place a capsular tension ring in every case where they suspect pseudoexfoliation.)

Recently, we’ve begun to see a clear association between late subluxation and pseudoexfoliation with capsular bag shrinkage, i.e., capsular phimosis. There are other causes for late sub-luxation, including

|

| One sign that the zonules are weak is wrinkling of the capsule when you touch it at the start of capsulorhexis. |

trauma, but this now appears to be the most common cause. Capsular phimosis is another warning sign of weakened zonules because the capsule is tugging on the zonular space. Unfortunately, studying subluxed lenses that have been retrieved has made it clear that a capsular tension ring doesn’t prevent phimosis, and thus doesn’t prevent late subluxation.

• If the nucleus is hard, consider using a prechopper and/or an ultrachopper (Alcon). These tools will help to break up the cataract without using as much energy inside the eye, helping to lessen the likelihood of complications and late subluxation. A modern version of a snare called the MiLoop (Iantech) can be used with hard cataracts and loose capsular bags to bisect the nucleus.

• Perform any rotation carefully. Even with a large ‘rhexis, this can be a source of zonular stress.

• Get all of the cortex out. Leaving cortex behind increases the likelihood of inflammation and can lead to Sommering rings later; that may lead to lens tilt and even pigment dispersion due to contacting the iris.

• Remove the cortex tangentially, not radially. Stripping the cortex tangentially is actually faster than radial stripping—and it’s safer. For many years we’ve been teaching that the surgeon should grab a piece of cortex, bring it to the center and re-move it. Most of us were taught to do it that way, but doing it that way actually increases the zonular stress. In contrast, doing it tangentially de-creases the stress on the zonules.

• Remove lens epithelial cells from the anterior capsule to reduce phimosis. Although some ophthalmic surgeons take the time to do this, the average cataract surgeon probably doesn’t, for at least three reasons: it’s time-consuming; it requires using an extra instrument; and you have to know how to do it. Usually, lens epithelial cell removal takes an extra 30 seconds, which can add up over the course of the day if you’re performing 100 cases a day. But the reality is that these cells are what leads to phimosis, so if you have any reason to suspect pseudoexfoliation, you’d better take the time to do it. (I do it on 100 per-cent of these patients.)

• Keep learning, because new information can make a big difference. As noted, we used to think it was OK to work through a small pupil, and that radial stripping was better than tangential stripping. Now we know better. The moral is, you shouldn’t be doing the same thing you’re doing today a year from now, because that means you’re behind the times. We all need to keep learning and adaptingand incorporate the new techniques and information into our surgeries.

Playing It Safe

Although the presence of pseudo-exfoliation is obvious in some patients, we currently have no way of knowing for certain if any given patient has pseudoexfoliation that we can’t see. That’s the reason we should always assume that pseudoexfoliation is a potential problem. It’s a very real risk, particularly in the glaucoma setting—but if we approach every case as if it’s a potential problem and perform the surgery accordingly, the risk for complications and late subluxation should decrease dramatically. REVIEW

Dr. Crandall is clinical professor, senior vice chair of ophthalmology and visual sciences, and director of glaucoma and cataract at the Moran Eye Center at the University of Utah.

1. Zaugg B, Werne L, Neuhann T, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of capsulorhexis phimosis with anterior flexing of single-piece hydrophilic acrylic lens haptics. J Cat Refractive Surg 2010;36:1605-1609.