Hysteresis Matters

John Berdahl, MD, Sioux Falls, S.D.

|

Ever since an ophthalmologist discovered that corneal thickness plays a role in glaucoma, we’ve been wondering about the role of biomechanics in this disease. Initially we thought that a patient with a thin cornea simply meant that we needed to adjust our IOP measurement to take corneal thickness into account. That’s true, but it turns out that having a thin cornea is also an independent risk factor for progression of glaucoma. It’s possible that a thin cornea is telling us something important about the biomechanics of the rest of the eye—especially the optic nerve head.

Measuring corneal hysteresis, or CH, is the next evolutionary step in the process of understanding this. CH is much more than a measure of thickness—it’s a measure of the shock-absorbing capacity of the cornea, and hence, the shock-absorbing capacity of the eye. (A high level of hysteresis means the cornea has a large capacity for shock absorption; a low hysteresis indicates a cornea with little capacity to absorb shock.)

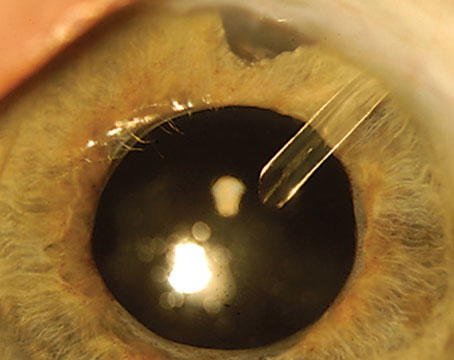

Hysteresis is calculated by measuring how the cornea deforms when pressure is applied and comparing that to how it returns to its normal shape. Reichert’s Ocular Response Analyzer uses high-speed imaging of the cornea during the application of air puffs to measure these corneal changes. From that it deduces the shock-absorbing capability, or hysteresis, of the cornea.

That corneal measurement may be telling us a lot about the shock-absorbing capacity of the optic nerve head—i.e., how much pressure the optic nerve head can tolerate. In fact, as the eye pressure goes up, the CH measurement goes down, which makes sense. The higher the pressure, the less shock-absorbing capability is left. It’s like loading a pickup truck with 2,000 pounds of weight; the shock absorbers squeeze down, and then there’s less shock-absorptive capability remaining. That’s what happens to the cornea—and possibly the optic nerve as well—when IOP goes up.

Hysteresis and IOP

In our practice we rely primarily on the ORA instrument when we measure IOP, for several reasons. First, the IOP measurements are very accurate. In fact, I trust the CH-adjusted measurement more than the Gold-mann measurement. If something isn’t adding up, or we’re making a surgical decision based on IOP, we’ll measure the IOP in multiple ways, including Goldmann tonometry, but even in that situation I put most of the weight on the CH-adjusted pressure measurement.

A second reason we rely on the ORA’s CH-adjusted IOP measurement is that the readings are easy to obtain, and they’re user-independent. That helps us with our patient flow. Furthermore, there’s no per-use charge, so it doesn’t cost us anything to do it (other than our time). In terms of reimbursement for performing the measurement, we do submit it to insurance, but often insurance denies it. In that case, we pass the cost on to the patient. But even if we weren’t charging anyone for it, I’d still use it.

Also, the CH-corrected IOP measurements are far less affected by refractive surgery than Goldmann, since altered hysteresis after refractive surgery is a prime factor in altering Goldmann readings. The ORA measurement compensates for that. (It also gives you a second measurement that’s an analog to a Goldmann measurement.) So we feel that we’re measuring the true pressure inside the eye, as well as gaining insight into the biomechanical state of the eye.

Beyond IOP

Of course, there are other reasons we check CH when working with our glaucoma patients, beside getting an IOP measurement that I believe is more accurate. Several studies1-4 have supported the usefulness of this for glaucoma management:

• Patients with a lower CH are more at risk of progression. An

important study confirming this was done by Felipe Medieros, MD, at Duke University.1 His prospective study showed that glaucoma patients with a lower CH—i.e., a lower ability to absorb the shock of increased IOP—progressed faster than patients with a higher CH, for a given level of IOP. So, if we find that a glaucoma patient has a low CH, we’re going to be more aggressive about treatment. We may be more inclined to intervene with a MIGS procedure if we were undecided, and we may move to a tra-beculectomy or tube shunt sooner.

• Patients with a lower CH are more likely to have undetected glaucoma. Because we measure CH in all of our patients, we decided to conduct a small study. We found that patients who came in with a lower CH had more advanced glaucoma—more visual field damage—on presentation than patients with a higher CH.2 This indicated that their glaucoma wasn’t detected as early as in patients at the same pressure who had a higher CH. To put it another way, having a low CH interfered with the timely detection of glaucoma. That is certainly useful clinical information.

Measuring pressure in the context of CH has been a big win in our practice, so we use it for all of our patients. It reassures us that we’re getting an accurate reading of the IOP, while providing other information that helps us manage our glaucoma patients more effectively. REVIEW

Dr. Berdahl is a corneal, refractive and glaucoma surgeon at Vance Thompson Vision in Sioux Falls, and associate clinical professor at the University of South Dakota. He reports no financial ties to any products discussed in this article.

1. Medeiros FA, Meira-Freitas D, Lisboa R, et al. Corneal hysteresis as a risk factor for glaucoma progression: A prospective longitudinal study. Ophthalmology 2013;120:8:1533-40.

2. Schweitzer JA, Ervin M, Berdahl JP. Assessment of corneal hysteresis measured by the ocular response analyzer as a screening tool in patients with glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol 2018;12:1809-1813.

3. Deol M, Taylor DA, Radcliffe NM. Corneal hysteresis and its relevance to glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2015;26:2:96-102.

4. Zimprich L, Diedrich J, Bleeker A, Schweitzer JA. Corneal hysteresis as a biomarker of glaucoma: Current insights. Clin Ophthalmol 2020;14:2255-2264.

Hysteresis Isn’t Essential

Robert T. Chang, MD, Stanford, Calif.

|

There’s increasing evidence in the published literature supporting corneal hysteresis (CH) as a risk factor associated with glaucoma and glaucoma progression. The Ocular Response Analyzer technology has been around for more than 15 years, and there are a few prospective longitudinal studies demonstrating benefit in glaucoma identification. However, when considering adding a significant capital expense with a modest, variable reimbursement, it’s important to look at when the CH number is clinically useful and whether it will actually improve glaucoma management, given that CH isn’t tracked or correlated with treatment success over time the way IOP or structural and functional optic nerve testing are.

At the moment, I don’t think adding a CH value will change overall therapeutic decision making very often. Like central corneal thickness, it’s merely a corneal behavior associated with glaucoma risk, mostly help--

ful in some glaucoma suspect cases.

Weighing the Pros and Cons

Here are some factors I’d consider before implementing corneal hysteresis as a regular part of my glaucoma protocol:

• In most glaucoma cases, knowing the corneal hysteresis doesn’t change our clinical decisions. I view low corneal hysteresis as an additional risk factor for glaucoma, similar to having a thin cornea. If you measured CH in every glaucoma patient along with the rest of the complete eye exam, how many times would that change your clinical decision, especially after you’ve already initiated treatment? We currently use multiple known risk factors such as age, ethnicity, family history, CCT, IOP and optic nerve appearance. Without another prospective longitudinal study like the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study, incorporating CH measurements along with known risk factors into a model designed to improve glaucoma risk assessment, we can’t determine the added value this would provide.

Granted, we know that CH can help adjust IOP measurements post refractive surgery and that lower CH can be worse for glaucoma, including low-tension glaucoma. However, CH can also change with age and IOP variability. In fact, its repeatability is actually adversely affected by IOP. Thus, a low CH isn’t good, but it’s not really a treatable or progression-based endpoint.

• A CH-adjusted, “more accurate” IOP measurement may not be a game-changer. Because glaucoma worsening is often measured over longer intervals, collecting additional “less accurate” Goldmann applanation and other multiple IOP data points helps to overcome the issue of not knowing the “true IOP” within what is already a variable diurnal range. Thus, clinical decision-making and targeted IOP treatment ranges already incorporate this imprecision. Adapting to CH-adjusted IOP endpoints would require new clinical trials, especially since CH changes with IOP.

• Including one more risk factor generally doesn’t change the bigger picture. It’s still not clear exactly why the association between hysteresis and glaucoma exists, although some hypothesize that it relates to optic nerve head structural changes and susceptibility. Whatever the reason for that association, in most cases a single risk factor doesn’t change our clinical decisions. If a glaucoma suspect’s only risk factor is low CH, would you treat based only on that value? Unless there’s a risk calculator incorporating CH, treatments can still be decided using structural and functional endpoints, along with CCT-adjusted IOP.

A Useful Tie-breaker

Of course, measuring corneal hysteresis can be helpful in some clinical situations. In particular, hysteresis becomes more valuable when other risk factors are uninterpretable or conflicting.

One longitudinal predictive study by Carolina Sussana, MD, et al., followed 278 glaucoma suspect eyes over four years.1 It did produce a multivariable model adjusting for age, IOP, central corneal thickness, pattern standard deviation and treatment, and CH was still predictive of development of glaucoma (hazard ratio=1.20; 95% CI: 1.01–1.42; p=0.040). However, the confidence interval is close to borderline.

|

The Bottom Line

I don’t see measuring corneal hy-steresis as essential, because it has a narrow range of use. In my experience, the percentage of patients in whom this value will change my treatment decision is small. As a stand-alone risk factor, it doesn’t have high sensitivity or specificity for diagnosing glaucoma, and it’s not a factor that we can try to adjust to help the patient. Even its repeatability is affected by IOP.

Although the ORA has been around for a long time, it’s still not common in all offices compared to OCTs and visual field machines. If it made a difference in the clinical realm for lots of patients, many more doctors would be using it. REVIEW

Dr. Chang is an associate professor of ophthalmology at Byers Eye Institute, Stanford University School of Medicine, in Stanford.

1. Susanna CN, Diniz-Filho A, Daga FB, et al. A prospective longitudinal study to investigate corneal hysteresis as a risk factor for predicting development of glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2018;187:148–152.