Peripheral ulcerative keratitis is a sight-threatening inflammatory condition that causes progressive peripheral corneal thinning. The incidence is estimated to be 0.2 to 3 individuals per million population.1 Prompt and aggressive treatment is needed to prevent not only corneal perforation but also morbidity and possible mortality in cases associated with a systemic collagen vascular disease.

Because of its association with underlying systemic disease, clinicians may need to put on their “rheum-ophthalmologist” hats to handle these tough cases. Here, I’ll discuss the workup, diagnosis and treatment of this condition using two case examples from my practice.

In the Periphery

PUK may result from local or systemic causes as well as infectious and noninfectious causes. The condition arises from a complex interaction of host autoimmunity, environmental factors, and the unique features of the peripheral cornea.2

Briefly, in contrast to the central cornea, the peripheral cornea has a well-defined vascular and lymphatic supply that allows access to the immune system. Inflammation in the peripheral cornea occurs when proteolytic enzymes from recruited cells are released via this route.3 Along with tight corneal collagen packing at the periphery, this allows for deposition of immune complexes such as IgM and C1 at the peripheral cornea4,5 and further destructive processes leading to corneal melting.

Clinical Presentation of PUK

The condition classically presents with pain, redness, tearing, light sensitivity and decreased vision. Patients have an area of crescent-shaped damage in the limbal region of the cornea with thinning present. There is always an overlying epithelial defect, and inflammatory cells may be present in the anterior chamber. Approximately 36 percent of affected patients will have an associated scleritis.6

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosing PUK requires meticulous clinical workup, including laboratory testing. The differential diagnosis for PUK includes:

- Mooren’s Ulcer, a diagnosis of exclusion often associated with severe pain.

- Degenerative conditions presenting with mild thinning, such as Terrien’s marginal degeneration, senile furrow degeneration and pellucid marginal degeneration. (None of these conditions has any pain or inflammatory processes associated with it.)

- Infection (comprising 19.7 percent of PUK cases)7 from bacteria, viruses, fungi, Acanthamoeba spp. and others.

- Neoplastic etiologies such as carcinoma in situ.

More than half of PUK cases are associated with a systemic collagen vascular disease. It’s crucial to identify these patients. They’ll need more than local treatment and may have a life-threatening condition.

Among the collagen vascular diseases associated with PUK, rheumatoid arthritis is at the top of the list, accounting for an estimated 34 percent of all noninfectious PUK cases with bilateral involvement.8 Others include polyarteritis nodosa, systemic lupus erythematosus, relapsing polychondritis and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides, which include granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Churg-Strauss syndrome and microscopic polyangiitis. Patients with these conditions may have involvement of other organs outside of the eye—notably the lungs and sinuses of those with ANCA-associated vasculitides, and the heart and kidneys of those with SLE.9

Workup

Workup for these patients includes rheumatoid factor (RF), inflammatory markers erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), and Quantiferon for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Tuberculosis sometimes presents with PUK, but more importantly, if you think the patient may need immunosuppression, ensure Quantiferon is negative (some drugs can reactivate latent TB).

Testing should also include antinuclear antibody (ANA) if there’s suspicion for a connective tissue disease. A titer of 1:160 or above is usually considered a positive test result. An ANCA screening can be ordered for suspected autoimmune disease such as vasculitis to determine whether the patient has one or both types of autoantibodies targeting myeloperoxidase (p-ANCA) and proteinase 3 (c-ANCA).

A chest X-ray and CT of the chest may also be ordered because ANCA-associated vasculitides may have sinus and pulmonary involvement, so you’ll want to rule these out before determining what type of treatment to put the patient on.

Treatment

In order to save the cornea, first lubricate it. With the epithelial defect, we’re always worried about superinfection, so antibiotic drops such as moxifloxacin can be used as prophylaxis. Vitamin C is added to bolster the cornea, and doxycycline is used because of its anti-metalloproteinase activity, which also helps to prevent further melting. Oral prednisone is given, dosed at 1 mg per kg.

Note: Topical steroids aren’t used in cases of corneal melting because we’ve found they may accelerate it. Think twice before using them and refrain from using them until the eye is stable. As for oral prednisone dosing, many clinicians will use much higher doses (60 to 80 mg) but it’s good to be cautious about the diminishing returns of very high-dose oral steroids. There comes a point where the risk-benefit ratio flips. Once you surpass about 80 mg of prednisone per day, the added benefit of a higher dose may not be significant compared to the extreme risk to the patient.

A few other treatments are needed to counteract prednisone side effects. Bactrim Double Strength is initiated to prevent opportunistic infection of the lungs. Any time a patient is immunosuppressed using more than 20 mg of prednisone daily for an extended period, they’re at risk for infection. Bactrim DS can be used, one tablet three times a week, as long as the patient isn’t allergic to sulfa. Otherwise, use an alternative medication for sulfa-allergic patients. Vitamin D and calcium are given to bolster the patient’s bones against prednisone. A proton pump inhibitor such as omeprazole is also commonly used to prevent ulceration of the stomach from the prednisone.

Lastly, in cases with severe corneal thinning, a shield at bedtime protects the patient from accidentally pushing on their eye and perforating the cornea.

|

|

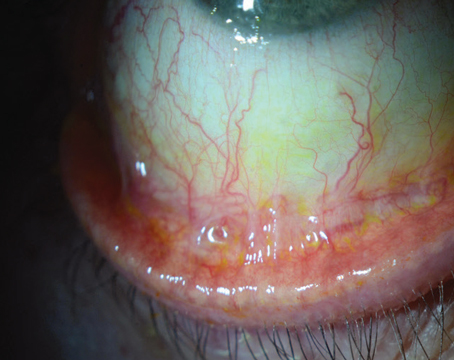

Figure 1. The right eye of the patient in Case 1 demonstrated nasal injection of the conjunctiva. Between 2:30 and 5:30 in the nasal cornea, there was significant corneal thinning. |

Case 1

An 82-year-old woman presented with a 10-day history of blurry vision, pain, redness and photophobia in the right eye. Her vision was 20/200 in the affected eye, which was a decrease from her baseline of 20/30. Her left eye was at baseline (20/400). Intraocular pressures were normal at 12 mmHg OD and 13 mmHg OS, and pupils were round with brisk reaction and no relative afferent pupillary defect.

On exam of her right eye, the eyelids were smooth and well positioned. The conjunctiva was injected nasally. At the nasal cornea, between approximately 2:30 and 5:30, there was significant corneal thinning (Figure 1).

At this point, the clinician should be suspicious for an underlying systemic disease. Laboratory testing can help identify why the patient is having this inflammation.

• Workup. This patient had negative/normal RS, ESR, CRP and Quantiferon. She had a positive ANA 1:160. Her c-ANCA screen was positive, 1:160 with a repeat of 1:320, so we were fairly confident with the reliability of these results. Her chest X-ray was within normal limits and the CT of the chest and sinuses had no concerning abnormalities.

• Treatment. Her treatment included:

— lubricating drops every two hours;

— moxifloxacin, one drop three times daily;

— vitamin C 500 mg to 1,000 mg daily;

— doxycycline 100 mg daily;

— prednisone 50 mg daily with a 10-mg taper every two weeks;

— Bactrim DS, one tablet three times per week;

— vitamin D/Ca++ daily;

— omeprazole 40 mg daily; and

— a shield at bedtime.

This particular patient had ANCA-positive testing, but because her manifestations were only ocular, the discussion with rheumatology found that using methotrexate was appropriate. Rituximab is the go-to in ANCA-associated disease, but in this case, the patient wasn’t willing to undergo treatment with infusion. She was started on methotrexate 20 mg weekly, and after about 12 weeks prednisone was completely tapered. At her last follow-up, about one year from presentation, she had no recurrent inflammation.

|

|

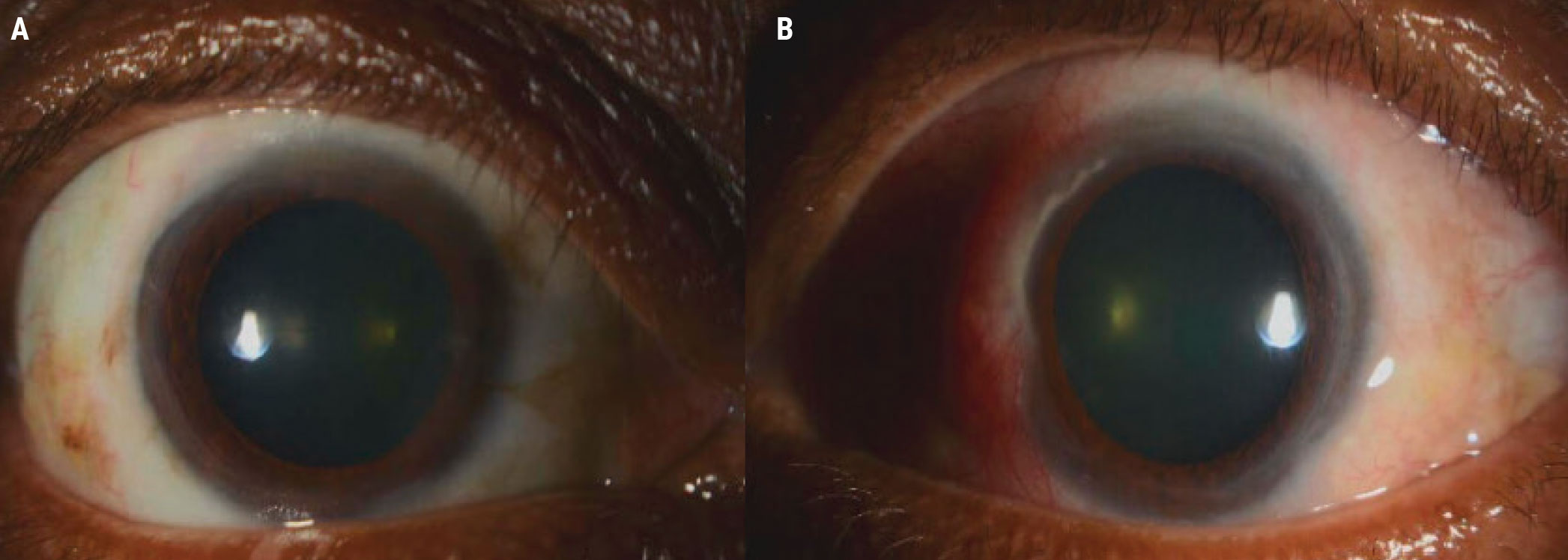

Figure 2A. The right eye (A) of the patient in Case 2 was unremarkable, but the left eye (B) had significant inflammation of the nasal sclera and conjunctiva. |

|

|

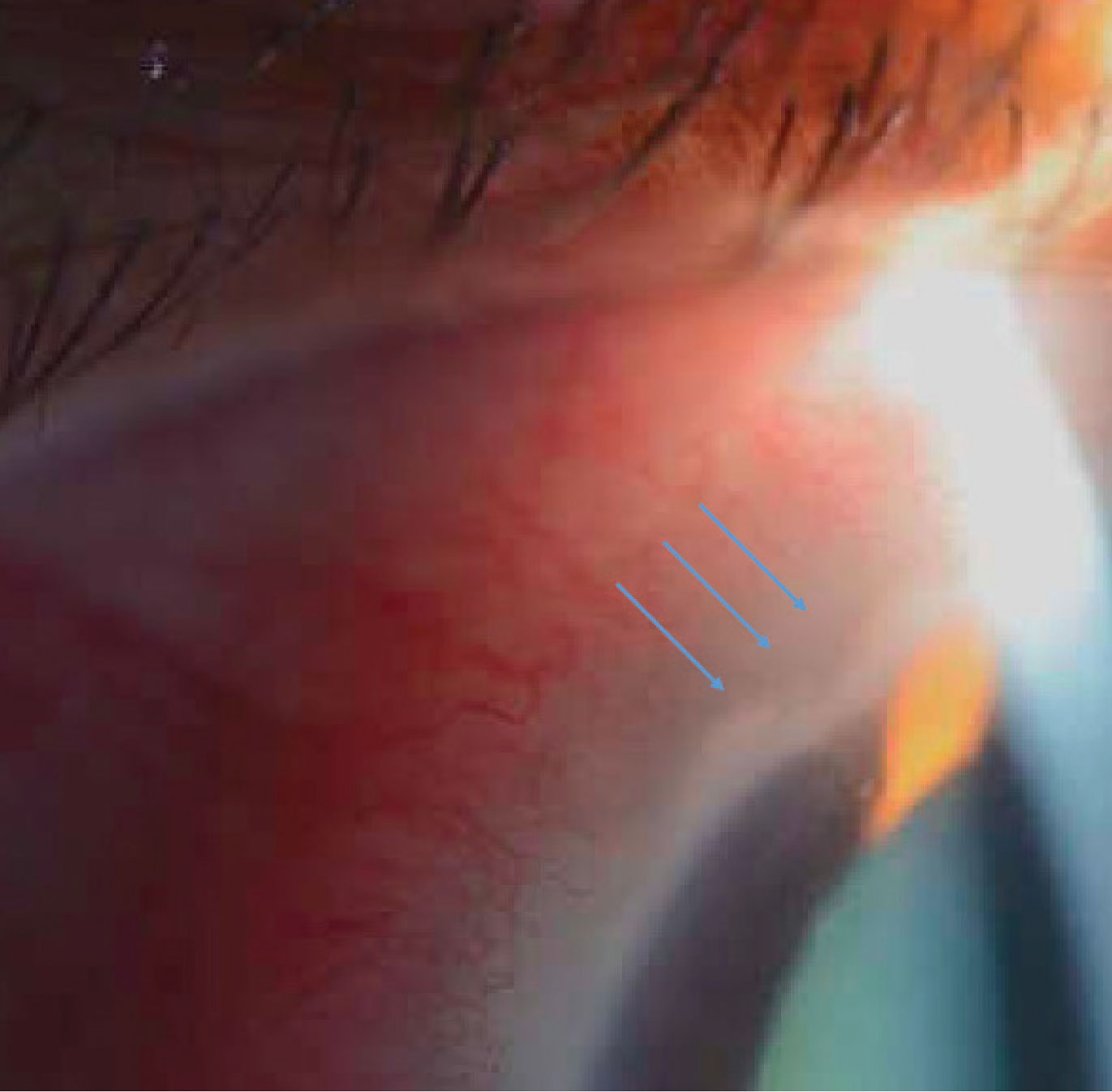

Figure 2B. Inflammatory infiltrates and an area of significant corneal thinning between 10:30 and 11:30 can be seen adjacent to the injection in the same patient. |

Case 2

A 52-year-old woman presented with a three-day history of blurry vision, pain, redness and photophobia in her left eye. Her BCVA was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/50 in the left, decreased from a baseline of 20/20. Intraocular pressures were within normal limits—12 mmHg OD and 13 mmHg OS. Pupils were round with brisk reaction and no relative afferent pupillary defect.

On exam, the right eye was unremarkable, but in the left eye of concern, the nasal section of the sclera and conjunctiva was injected about 3 to 4+ injection (Figure 2A). Adjacent to that injection, the cornea demonstrated some inflammatory infiltrates as well as an area of significant corneal thinning between approximately 10:30 and 11:30 (Figure 2B).

• Workup and treatment. Her workup was significant for rheumatoid factor positivity. ANCA, ANA, ESR, CRP and Quantiferon were negative. Initial treatment for PUK was the same as in Case 1. She was started on adalimumab subcutaneous injections every two weeks. She successfully tapered off prednisone over 12 weeks, and after four years of follow-up, she had no recurrence of PUK and no rheumatoid arthritis manifestation.

Other Treatments

The most acute complication to prevent is perforation of the cornea. In addition to starting steroids, you can either glue or resect the conjunctiva to avoid a surgical intervention such as corneal tectonic graft or full corneal replacement. Here are my approaches:

• Cyanoacrylate glue (off label). It’s thought that this glue prevents further melting and stabilizes the cornea by acting as a physical barrier to the inflammatory mediators entering into the cornea.10 At the same time, it provides tectonic support by filling in the area of thinning.

The technique I use involves punching a hole through part of a plastic drape using a 3-mm dermatologic punch. I put this on the end of a cotton tip, place a drop of glue on it and then apply it in the area of thinning. This is a nice, controlled way of administering the glue that prevents it from getting all over the cornea. A bandage contact lens is placed over the glue to protect the eyelid from irritation, since the glued area is rough and uncomfortable. The glue typically falls off after three to four weeks.

• Conjunctival resection. This technique has been described to prevent further thinning from PUK. I performed this procedure for the patient in Case 2, who had significant inflammation of her nasal sclera and conjunctiva, because the inflammatory deposits in her cornea would have increased without intervention.

When performing conjunctival resection, I use a toothed 0.12-mm forceps and Wescott scissors. After injecting subconjunctival lidocaine with or without epinephrine, I cut along the limbus, making sure to hug it. Then, I cut about 3 to 4 mm posterior to the area of thinning or posterior to the cornea, just to make sure there’s a nice space between the conjunctiva and cornea.

Uncovering Systemic Disease

If a patient has an uncontrolled systemic disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, or they come off their systemic treatment for one reason or another, they can develop flares that include ocular inflammation and PUK. Some patients aren’t aware they have an underlying condition, and the ophthalmologist may be the one to make the diagnosis.

Anytime you see a patient with an inflammatory eye disease, you want to do an excellent history. That will guide you in many instances. In the case of rheumatoid arthritis, you can examine the patient’s hands and look for the classic swan-neck joints or nodules. With ANCA-associated vasculitides, ask about nosebleeds or coughing up blood. If your review of systems and exam are negative, perform the bloodwork anyway, because these types of joint changes or nosebleeds are characteristic of late changes of those diseases.

Many cornea and uveitis providers are comfortable sending off the initial workup and enlisting the help of rheumatology once they find the results, but it all depends on your training and comfort level. This may be more difficult in non-academic settings or those far from an academic center because some of the labs may not be accessible.

Most ophthalmologists are less comfortable prescribing immunomodulating therapy because of the amount of monitoring that’s required. Oftentimes, this is handed off to rheumatologists, though there are uveitis specialists who are very comfortable with systemic immunosuppression and will do all of this themselves. Nevertheless, being part of the treating team involves close collaboration with rheumatology.

The most important thing to keep in mind is that if a patient has a life-threatening autoimmune condition they must be immunosuppressed. If the patient doesn’t receive adequate immunosuppression, there’s significant mortality from inflammation affecting other parts of the body. In the literature, scleritis with rheumatoid arthritis has 30- to 45-percent mortality at five years.

In conclusion, PUK is a vision-threatening condition that requires prompt treatment to stabilize the cornea. Don’t wait until tomorrow to intervene. First, identify the underlying cause, because more than half of the time, there’s an associated systemic condition that will require appropriate treatment. Based on the lab findings, select the best immunomodulating medication or treatment plan for the patient, though of course the patient has to be willing to undergo the type of treatment you choose, since many treatments such as infusions are very time consuming.

Dr. Kombo is an assistant professor and director of medical education of the ophthalmology and visual science department at Yale School of Medicine. She has no related financial disclosures.

1. McKibbin M, Isaacs JD, Morrell AJ. Incidence of corneal melting in association with systemic disease in the Yorkshire region, 1997-1997. Br J Ophthalmol 1999;83:941-943.

2. Gupta Y, Kishore A, Kumari P, et al. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Surv Ophthalmol 2021;66:6:977-998. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2021.02.013.

3. Messmer EM, Foster CS. Vasculitic peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Surv Ophthalmol 1999;43:379-396.

4. Allansmith MR, McClellan BH. Immunoglobulins in the human cornea. Am J Ophthalmol 1975;80:123–132.

5. Mondino BJ, Brady KJ. Distribution of hemolytic complement in the normal cornea. Arch Ophthalmol 1981;99:1430–1433.

6. Sainz de la Maza M, Foster CS, Jabbur NS, Baltatzis S. Ocular characteristics and disease associations in scleritis-associated peripheral keratopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:1:15-19.

7. Sharma N, Sinha G, Shekhar H, Titiyal JS, Agarwal T, Chawla B, Tandon R, Vajpayee RB. Demographic profile, clinical features and outcome of peripheral ulcerative keratitis: A prospective study. Br J Ophthalmol 2015;99:11:1503-8.

8. Hassanpour K, ElSheikh RH, Arabi A, et al. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis: A review. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2022;17:1:252-275.

9. Cojocaru M, Cojocaru IM, Silosi I, Vrabie CD. Manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Maedica (Bucur) 2011;6:4:330-336.

10. Fogle JA, Kenyon KR, Foster CS. Tissue adhesive arrests stromal melting in the human cornea. Am J Ophthalmol 1980;89:795-802.