Here, three surgeons with extensive experience using this technology share their latest thoughts about what topography-guided ablation is capable of, and the pros and cons of using it.

Expanding the Niche

A. John Kanellopoulos, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology at New York University Medical School and medical director of the Laservision.gr Institute in Athens, Greece, has performed topography-guided procedures using the WaveLight platform since 2003, treating more than 4,000 cases. “We began by using it to treat irregular corneas such as those with decentered laser ablations and irregular pathology such as contact-lens-related ulcers, trauma and so forth,” he says. “We moved on to using this technology to normalize some eyes with naturally occurring irregularities, such as keratoconus.

“Our experience has proven that topography-guided systems are a very reliable way to document most of the aberrations of the human eye and transfer them to treatment,” he continues. “More than 90 percent of human visual aberrations are the result of irregularities in the cornea, and this is especially true in eyes that have had previous surgery or have acquired irregularities. Employing topography-guided treatment, these conditions can be addressed to the maximum, without the variability that wavefront-guided treatment—potentially the counterpart of topography-guided treatment—can offer.”

“It’s incredible to be able to take an irregular cornea and improve the patient’s quality of vision,” says Raymond Stein, MD, FRCSC, medical director of the Bochner Eye Institute in Toronto, and associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Toronto.

|

Dr. Kanellopoulos observes that topography-guided ablation is very common in many countries outside the United States and is considered time-tested. “Outside the U.S., in addition to the Nidek and the WaveLight platforms that have been FDA-approved, many laser platforms have topography-guided options,” he points out. “Zeiss has a topography-guided option in its excimer laser; Schwind does as well; and another one is made by Ivis, an Italian manufacturer. Depending on the practitioner, I think refractive surgery centers use this technology in anywhere from 10 to 50 percent of their patients. Some centers use it purely for therapeutic purposes to treat irregular corneas and eyes with pathology, either after a laser procedure or after an accident, or eyes with naturally occurring irregularities. Some centers, like ours, view topography-guided treatment as a way to customize and further enhance laser vision correction.

“The FDA gave approval for topography-guided treatment using either the Alcon or Nidek systems in October 2013, but neither system is currently used in the U.S.,” he adds. “Alcon is planning to roll out its use in 2015. But it should be noted that the FDA approval was for use in normal eyes. Obviously the main interest most surgeons have in employing topography-guided ablation is in abnormal eyes, and potentially in hyperopic eyes.”

Using the Technology

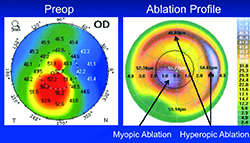

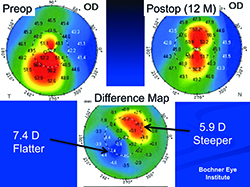

One of the things that separates topography-guided ablation from standard ablations is the strategy it employs to level out the corneal surface. “With wavefront-guided ablation, typically the mountains would simply be flattened, and it would require a significant amount of flattening to equalize the whole cornea,” explains Dr. Stein. “Topography-guided ablation elevates the valleys as well, so the mountains don’t have to be flattened nearly as much. That means less tissue removal to achieve the goal of improving vision quality. We typically remove about 50 µm.

| ||||||||||

“Over time we’ve learned that the best candidates for this type of treatment are corneas that have less than a 10-D difference between the steepest and flattest parts of the cornea,” he adds. “In that situation we can flatten the steep areas by about 5 D and steepen the flat areas by about 5 D. That’s about the maximum we can hope to achieve. We’ve had many patients who came in with less than a 10-D difference between the low and high parts of the cornea, and a reasonably thick cornea, who went from 20/200 best-corrected spectacle or soft-contact-lens acuity to 20/25 or 20/30 best-corrected. But if a patient has a 20-D difference between the steepest and flattest parts of the cornea, we can’t hope to achieve the same degree of improvement in best-corrected spectacle visual acuity.”

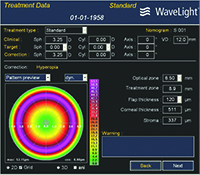

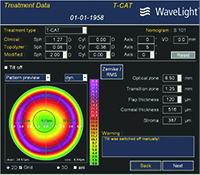

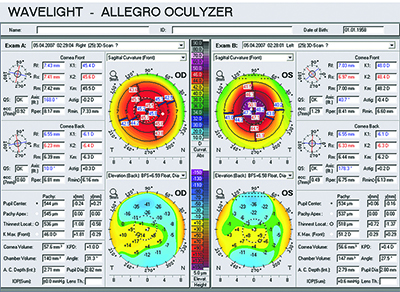

Dr. Stein describes a typical procedure in his practice. “The technician captures eight images using an equivalent of the Pentacam—WaveLight’s Oculyzer—which are digitally transferred to the excimer laser,” he says. “We do eight images because we want to maximize the data quality; more than eight would be too time-consuming. We review the data and eliminate the outliers; then we devise a treatment protocol. We schedule these patients on the same day we do laser vision correction patients. So if I’m in the OR I’ll do PRK and LASIK cases; then I’ll do a topography-guided PRK. After that, the patient will have cross-linking done by another member of our staff; that takes longer.”

Placido Disc or Tomography?

Of course, there are several ways to evaluate the topography of a cornea. Surgeons say each method has some limitations. “Both placido disc-based topography-guided treatments and Pentacam-based topography-guided treatments have some intrinsic shortcomings,” notes Dr. Kanellopoulos. “Placido disc relies mainly on a cornea having an adequate tear film, while the Pentacam relies on a cornea being clear and translucent. As a result, their effectiveness depends on the pathology. For instance, a corneal scar would be better treated with a placido-disc-based topography-guided treatment because that technology is not affected by the clouding of the cornea. On the other hand, if a patient has a less-than-optimal tear film or a very irregular cornea, Pentacam-guided treatment may be the best way to go. Unfortunately, it appears that users in the United States will not have the Pentacam-driven option, even though it’s available in many platforms, because that would entail a separate FDA approval process. That does not seem feasible in the near future.”

Dr. Kanellopoulos says that one advantage of placido disc technology is that it’s currently available in the Alcon platform with cyclorotation adjustment. “As you might imagine, this can be a pivotal part of getting excellent results, especially when treating irregular corneas or corneas with high astigmatism,” he says. “That’s true even if tomography might be slightly better than placido disc, if that particular patient happens to have significant cyclorotation. Even 2 degrees of cyclorotation becomes extremely significant in topography-guided treatments of irregular corneas or corneas with high astigmatism or angle kappa, because every 2 degrees of cyclorotation reduces the astigmatic efficacy by 8 percent, which is astounding.”

Dr. Kanellopoulos says that today he prefers to use both topography and tomography. “I like to compare both options, and also compare them to the standard ablation profile for that refractive error, as well as the results of very thorough slit-lamp biomicroscopy,” he explains. “I may also compare their readings to an objective measure such as the Cassini’s multicolor LED reflection topography and an epithelial map obtained by anterior segment OCT. This gives me a lot of input regarding whether the treatments are different, and if so, how. That information then helps me to determine which of the two will be better for the patient.” Dr. Kanellopoulos notes that he and his colleagues have reported extensively on this in the past two years at the major annual meetings and published several papers on it.

Issues Slowing Adoption

Despite the widespread availability of topography-guided ablation outside the United States, its use is nowhere near that of standard laser procedures. “The problem is not the technology,” says Simon P. Holland, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. (Dr. Holland has used topography-guided ablation at the Pacific Laser Eye Centre in Vancouver, working with David T. C. Lin, MD, since 2004.). “The current lasers are generally excellent, and the results we’re getting are very good. However, the number of patients who would clearly benefit from it is relatively small. The market is mainly patients who’ve had difficulty, such as ectasia, post-keratoplasty irregular astigmatism, previous injuries or corneal scars.

“The other indication, which keeps us busiest, is keratoconus,” he continues. “That’s really opened up in the past few years because we now have cross-linking, and we’ve found that it’s safe to take a limited amount of tissue, providing that the cornea is subsequently cross-linked to maintain its strength. We’ve done about 650 eyes using two different machines in the past six years since cross-linking became available to us, and about two-thirds of those were keratoconus. There’s a great need for this type of procedure in these patients, but again, the number of patients in this situation is relatively small compared to the overall population of people needing refractive treatment.”

Dr. Holland says a second issue limiting the popularity of topography-guided ablation is the learning curve. “It’s difficult to get started using this technique,” he says. “Every case has to be customized. For example, if you’re doing transepithelial ablation, the variable thickness of the epithelium has to be taken into consideration. So it’s very hard to translate one treatment onto another patient. That means you can’t use the technology right out of the box and expect to get great results—you really have to build up your experience and look at your data. Eventually you learn what’s most likely to produce a good result in each case.”

Dr. Stein agrees. “I think you have to do at least 50 cases to become really adept,” he says. “The patients should do reasonably well in those first 50 cases, but they’ll do even better after the first 50. Once the surgeon has the experience, treatment decisions can be made pretty quickly.”

Addressing Different Conditions

Surgeons note that there are a number of indications for which topography-guided treatment is an excellent option, including irregular corneas from focal scars, keratoconus, pellucid marginal degeneration and ectasia following laser vision correction.

• Keratoconus. Dr. Stein says this is the number one indication for topography-guided ablation in his practice. “Cross-linking is successful in stopping the disease from progressing in close to 98 percent of these patients,” he notes. “But patients want us to take it one step further—they want an improvement in their quality of vision so they won’t need a rigid gas permeable contact lens in order to see. That’s what combining topography-guided ablation with cross-linking can offer them. In a high percentage of patients we can eliminate the need for RGP lenses, allowing patients to wear glasses or soft contact lenses. This is really a huge advance in our ability to help these patients.”

Dr. Stein agrees, noting that he introduced cross-linking into Canada about seven years ago. “The first four years, we simply did cross-linking for the patients with keratoconus, ectasia and pellucid marginal degeneration,” he says. “Today, in 90 percent of these cases, we do topography-guided PRK in addition to the cross-linking.”

• Hyperopia. Hyperopes often achieve better outcomes when treated with a topography-guided refractive procedure. “In my opinion, topography-guided ablation is the equivalent of a successful treatment in hyperopes,” says Dr. Kanellopoulos. “For many years we’ve advocated using topography-guided ablation in all hyperopic eyes because they tend to have significant angle kappa. Topography-guided ablation treats on the cornea apex by default; that’s usually the position of the visual axis.”

Dr. Stein agrees. “We do a high percentage of our hyperopic PRK and LASIK using topography-guided procedures, and we’re getting better refractive outcomes,” he says. “I think you’re going to see a lot more of this down the road.”

• Post-LASIK and PRK problems. Dr. Stein notes that topography-guided ablations are excellent for treating complications following LASIK or PRK, such as irregular astigmatism or a small optical zone. “With topography-guided PRK we can enlarge the optical zone and give patients better quality of vision,” he says.

• Post-radial keratotomy. “A lot of RK patients who were done 20 years ago are now undergoing cataract surgery, and a lot of these corneas are somewhat irregular,” Dr. Stein points out. “If a surgeon performed an eight-incision RK but made some incisions deeper than others, for example, that would probably induce some irregular astigmatism. With topography-guided PRK we can try to smooth out the irregular cornea before the cataract surgery. We’re doing this on quite a few patients now, and I see this as a significant application down the road.”

• Unhappy 20/20 patients. “We’ve had some fascinating cases—people who have 20/20 vision and complain that they can’t see well,” notes Dr. Holland. “When we image them we find that there’s a subtle area with inferior steepening that’s generating aberrations. Often these are patients whose vision could be corrected by wearing a rigid lens, but they are intolerant. I understand that few surgeons want to treat a 20/20 eye, but we have done some cases like this and the results have been promising.”

• Arcuate astigmatic incisions. Another source of corneal irregularity that Dr. Stein has encountered is arcuate incisions made years ago to correct astigmatism. “If you make an arcuate cut to treat astigmatism—as many surgeons did in the past—that’s more central and not the proper depth, you can induce irregular astigmatism. That’s another application for topography-guided PRK.”

Improving Normal Vision

“Another intrinsic advantage of topography-guided became clear with the recent FDA study conducted by Alcon,” says Dr. Kanellopoulos. “Even as a seasoned topography-guided surgeon, I have learned a lot from that data. We’ve always known that topography-guided treatment is better for irregular and hyperopic eyes, but the FDA data has shown that even virgin eyes can benefit from this. A very large percentage of normal eyes in that study gained lines of vision. This probably has to do with subtle corneal irregularities that normal eyes have. These subtle irregularities are addressed by topography-guided ablation. This appears to enhance visual function.

| ||||||

Dr. Kanellopoulos says that this has led him to do all of his cases, including the routine ones, using topography-guided treatment. “I see a significant advantage in the fact that it can further normalize even apparently healthy corneas, offering better visual acuity and an increase in lines of vision,” he says.

Dr. Holland agrees, particularly when eyes have a little bit of irregular astigmatism. “When we look at our routine PRK and LASIK cases today, we ask whether the corneal aberrations are consistent with the patient’s re-fraction,” he says. “If they are, we consider the possibility that the patient would benefit from correcting that slight degree of irregularity with a limited topography-guided treatment.”

Managing Altered Refraction

One of the concerns with topography-guided ablation is that while smoothing the cornea it may alter the refraction, potentially leading to a refractive surprise.

“Practice has proven that when you treat virgin eyes with topography-guided ablation there’s really no significant care or extra nomogram that one needs to employ,” says Dr. Kanellopoulos. “However, when you employ topography-guided ablation in irregular eyes, it can significantly change the spherical refractive error; you may end up with some residual hyperopia or myopia. In my opinion this is not a significant issue because the procedure is employed in these eyes mainly to improve best-corrected visual acuity; one should expect that a second refining procedure to address the refractive error may be necessary.”

Along these lines, Dr. Stein points out that they sometimes end up reducing the quality of a keratoconus patient’s uncorrected acuity in order to improve his best-corrected acuity. “That’s a very important point that patients need to understand,” he says. “We discuss that in depth with them. They may come in with an uncorrected acuity of 20/50 and a best-corrected acuity of 20/40. By smoothing the cornea and doing cross-linking we may reduce their uncorrected acuity to 20/80, but we improve their best-corrected acuity to 20/25, so they get much better quality of spectacle- or contact-lens-corrected vision. This is not typical with LASIK or PRK. There, the patients want the best uncorrected visual acuity; that’s why they come in. But in this case, we want to halt the progression, and second, improve their best-corrected acuity.”

Dr. Kanellopoulos says that a common mistake made by surgeons just starting to use topography-guided ablation is overmanipulating the Q-value, which reflects the asphericity of the cornea. “In order to improve Q-value the laser will perform a hyperopic-type correction that will induce myopia,” he explains. “This is a general rule. For example, if we try to convert the Q-value in an eye that’s between -0.1 and -0.5, this will induce 0.5 to 0.75 D of myopia. A seasoned topography-guided surgeon will anticipate this. But for a novice topography-guided surgeon, this may be a refractive surprise. Generally, more complicated cases with an extremely irregular ablation pattern are more likely to create a significant refractive change.”

Dr. Kanellopoulos notes that most topography-guided surgeons are aware of the issue. “Experienced users of topography-guided ablation have acquired the ability to predict that refractive shift and adjust the treatment accordingly, to preempt the anticipated refractive error,” he adds. “We call this ‘topography neutralization.’ This, of course, is a cookbook approach by the surgeon; it helps to reduce the number of potential retreatments that are required in these patients.”

Offsetting the Change

Some surgeons have developed nomograms to address this potential refractive change by compensating during the procedure; others prefer to wait.

“The topography-guided technique we’ve used the most, which was pioneered by my partner, David Lin, MD, is the customized topographic neutralization technique, or Custom TNT,” says Dr. Holland. “Using this protocol we first try to improve the topography; then we add the astigmatism correction; then we add the spherical correction. This approach allows us to compensate for the refractive effects of the surface smoothing. For instance, when treating most keratoconus, you’re trying to flatten the steep part, but you have to compensate for that by steepening the periphery. That creates a peripheral trench that gives you a hyperopic effect, which then induces myopia. So, you have to compensate for that by treating for additional myopia; if you don’t, the patient will end up myopic.”

Dr. Stein says he generally doesn’t try to correct the spherical error when performing the topography-guided ablation. “We generally save that for a separate procedure,” he says. “The final refractive error is not totally predictable, so our main goal is to improve BCVA.”

Dr. Stein adds that if the patient has a significant refractive error, he wouldn’t do LASIK to correct it later. “LASIK would weaken the cornea because of the flap,” he notes. “If the prescription was a nominal one, and the patient has a reasonable corneal thickness, then we might consider a PRK at a later time. But you have to be very careful about removing more tissue and weakening the cornea. Also after cross-linking, if we do PRK down the road, the results are not as predictable. However, in patients who have a significant refractive error and really want an improvement in uncorrected acuity, we have the option of a toric implantable contact lens such as Visian—if the patient is a candidate for an ICL—once the refraction is stable. That might eliminate the patient’s need for contact lenses or glasses.”

Topo-guided vs. Wavefront

“The difference between topography-guided ablation and wavefront ablation strategies is very simple,” says Dr. Kanellopoulos. “Wavefront-guided ablation works by reducing the corneal tissue to a lower level. It removes a lot of tissue in order to make the cornea more spherical, based on the flattest part of the cornea. In contrast, topography-guided uses a bimodal treatment; it aims to shave off the peaks of corneal curvature and steepen flatter areas indirectly by ablating around them. This bimodal approach gives topography-guided ablation a tremendous advantage, in my opinion. It ablates much less tissue than wavefront-guided ablation—in some instances one-third as much tissue.

“Another significant difference between these types of treatment is that topography-guided treatment is almost always possible, even in very irregular eyes,” he continues. “In contrast, wavefront-guided treatment becomes very challenging or impossible in eyes with high refractive error or significant irregularity.”

Is one of them better for treating irregular astigmatism? “My experience has been that if it’s a small irregularity and mild astigmatism in a cornea with a lot of tissue, then wavefront-guided and topography-guided may be equivalent,” Dr. Kanellopoulos says. “But in cases where it’s really important to correct the irregularity, such as cases needing higher astigmatic correction and not having the tissue reserves that you would want in order to treat with wavefront-guided, topography-guided becomes the only option. In addition, we have clearly shown that topography-guided collagen cross-linking coupled with a topography-guided excimer ablation can maximize the refractive change in the cornea while reducing even further the amount of tissue you need to ablate.”

Dr. Kanellopoulos notes that he also finds it much easier to understand and predict the changes that will be produced by topography-guided treatments. “Wavefront is an approach that has a lot of theory in it that I can’t necessarily grasp by looking at objective data,” he points out. “And again, the human wavefront is a dynamic entity; it’s very difficult to capture reproducible wavefront maps. Furthermore, if there is variability in the wavefront maps it’s very difficult to decide which is the representative wavefront map that should be used for treatment in that patient.”

Dr. Holland agrees, noting that another advantage is being able to decide whether or not to treat crystalline lens-related aberrations in older patients. “You may or may not want to treat those, depending on the age of the patient,” he says. “I think that accounts for the popularity of wavefront-optimized rather than wavefront-guided treatments.”

Dr. Stein adds that the number of data points on which the treatment is based is far higher with topography-guided ablation. “With a very sophisticated wavefront unit you might collect 1,000 data points,” he says. “With the topography unit we capture more than 20,000 data points. There’s less potential for error because we’re capturing more information on which to base the ablation.”

Given that wavefront and topography measure different things, what about combining the two measurements to guide ablation? Dr. Kanellopoulos says the WaveLight research team has been working on this approach. “This is a very exciting new entity called ray tracing,” he says. “It’s been reported in the literature, showing astounding accuracy in determining refractive error, and has all the benefits that topography-guided treatment can give in terms of quality of vision. So there is a significant advantage to combining them.

|

When You’re Starting Out

Dr. Stein offers some suggestions for surgeons just starting to offer this type of procedure. “First, don’t pick corneas that are too thin or have any significant scarring,” he says. “Second, make sure your technicians are capable of capturing relatively consistent maps. Third, make sure the cornea is not too dry or wet when the imaging is done. Fourth, make sure the treatment is about 50 µm or less, unless the cornea is unusually thick.

“Finally, if you’re just getting involved with this technology, spend some time with a surgeon who has experience—experience that involves many different types of eye conditions,” he adds. “ Every type of corneal problem you may encounter will be a little different, whether it’s radial keratotomy, a decentered ablation, irregular arcuate cuts, ectatic eyes or keratoconus patients. No article or textbook you can read will give you the experience you need to become good at this.”

“As with any new procedure, you should underpromise and overdeliver,” says Dr. Holland. “Patient expectations are high, so it’s probably best to start off by telling patients that they may need a second treatment. In fact, we used to do topography-guided treatments in two separate steps. We’d explain to the patient that we were going to first regularize the cornea and improve the topography; then, after everything settled down—which could take as long as a year—the patient would come back in for the refractive treatment. Today we use the TNT procedure [described earlier], where we modify the topography and do the refractive treatment in one sitting. But if you’re just starting out, separating the two parts would be the safer way to go. At the very least, you need to warn the patient that you can only do a limited refractive treatment with this technology; you don’t want to be too aggressive when you start.

“In addition, it’s helpful to begin by treating astigmatic patients such as post-keratoplasty, rather than more complex cases,” he says. “And it’s important to remember that it takes a long time for vision to stabilize after the treatment. Do not retreat too early. Epithelial remodeling can take three to six months, and if you do cross-linking as well, then you’re talking about a year. A keratoconus patient, in particular, can take a long time to stabilize. If necessary, fit the patient with soft contact lenses during this time, and make sure to follow his progress closely.”

Looking to the Future

|

“In the meantime, using this approach is definitely worthwhile, in our hands,” he says. “We’ve gotten some dramatic results—and only a few disappointing ones—with ectasia, post-keratoplasty and keratoconus patients. In our ectasia group, for example, about one-third of our patients gain two or more lines of BCVA. About a third of them end up 20/40 uncorrected or better. It’s a huge result for these patients who are being handicapped by the severe irregular astigmatism that they get. The extra effort it takes to do these treatments is definitely worthwhile.”

“I have to say that topography-guided ablation, especially when it’s combined with cross-linking, is a remarkable procedure,” adds Dr. Stein. “We’re able to take patients who are not functioning well and improve their best corrected visual acuity. It’s one of the most enjoyable parts of my practice.” REVIEW

Dr. Kanellopoulos is a consultant for WaveLight, Alcon, iOptics and Avedro. Drs. Stein and Holland have no financial ties to products or companies mentioned.