Surgeons say that the success of modern cataract surgery, both with premium lenses and high-quality monofocal IOLs, can push some patients to visit their ophthalmologist to try to get cataract surgery—medically justified or not—in an effort to “get what my neighbor got.” Some of these patients are even savvy enough to work the system by claiming visual difficulties.

To avoid committing insurance fraud and exposing these individuals to unnecessary risks, surgeons say there are certain measures you can take. They’re quick to add, however, that just because a patient’s attempt at insurance- or Medicare-paid surgery is rebuffed doesn’t mean he won’t want to spring for it himself in the form of refractive lens-based procedure, and they offer further advice on making sure the right patient gets the right procedure—or none at all.

|

“I Think I Have a Cataract”

Boulder, Colorado, ophthalmologist Mark Packer says that though malingering in most of medicine is usually done to qualify for some sort of disability payment, it can take on a new form in ophthalmology.

“There aren’t a lot of examples in other fields where someone is malingering in order to get an operation, other than Munchausen’s syndrome,” he says. “But in ophthalmology, I’ve definitely seen this. I guess it arose even before the Medicare ruling in 2005 regarding presbyopic IOLs. Before that, patients were aware that their friends went to see the ophthalmologist for cataract surgery, and that they used to wear bifocals but now they don’t. This would lead them to my office, saying something to the effect, ‘I don’t have cataracts but I want that.’ But then they find out it will cost $10,000 because they don’t have cataracts. ‘But my neighbor didn’t pay anything—the insurance paid for it!’ You reply that that’s because the neighbor had cataracts. ‘So,’ he thinks, ‘what does it take to have a cataract? Maybe I can find one.’”

It turns out, however, that if a patient really wants to say he has poor vision, this can be difficult to disprove just by using visual acuity charts. “They can see the size of the letters,” Dr. Packer says. “They might know what 20/40 looks like or, if you’re using an older chart, it might say ‘20/40’ right on the chart. While today we have randomized, digital charts that no one can memorize, if someone’s motivated to lie to get the surgery paid for by Medicare or insurance, it can still be hard to prove that someone is malingering, just by using visual acuity.”

At this point, if you simply don’t believe what a patient is saying for some reason, it would be easy enough to smack the patient down as dissembling and refuse to do the surgery. However, surgeons say the effect of this is to alienate a member of your community, as well as all of that person’s family members and friends. “It’s helpful to have some other workarounds that maybe patients aren’t as familiar with, but which can provide evidence that they’re not really a candidate for medically-reimbursed cataract surgery,” Dr. Packer says. “I’ve got a few of those up my sleeve.”

|

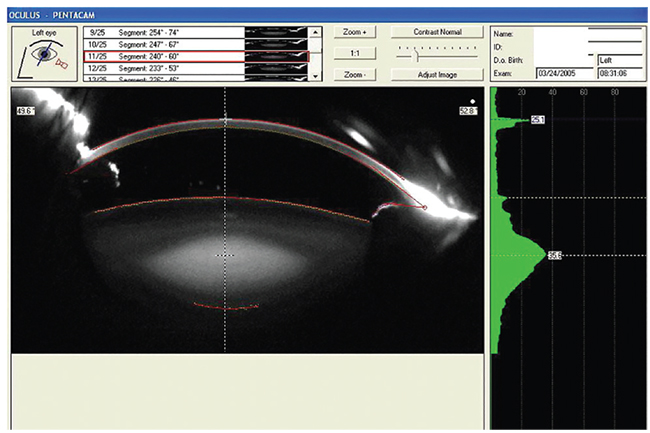

| Scheimpflug imaging can provide an objective grading of a cataract that can help in borderline cases, surgeons say. |

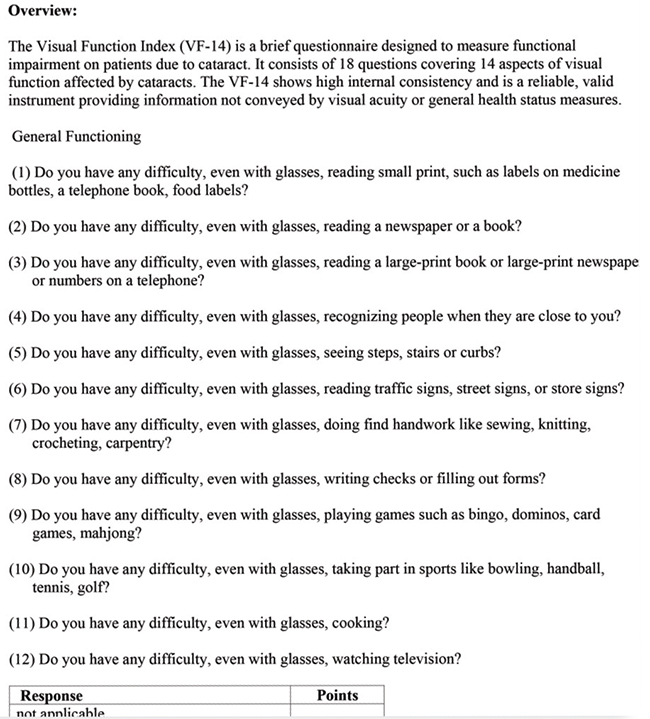

Since physicians say visual acuity can be “squishy” and easy to manipulate, one of the first ways to weed out a less-than-truthful patient is with the VF-14 visual function questionnaire. “It has such questions as, ‘Do you drive?’ and ‘If you drive, is it difficult?’” says Dr. Packer. “A patient doesn’t know what the score on that is supposed to be, or what a realistic score would be for someone with the degree of visual disability that he’s claiming to have—but I do. So, if the vision is 20/50, for instance, in general that correlates with a VF-14 in the range of 60 to 75. If it’s better than that, such as an 88, then there’s no reason to have cataract surgery, because that’s the average score for individuals who’ve had the surgery. In that case, there’d be no room for improvement.”

Contrast sensitivity is another test about which patients have little understanding, so they can’t easily manipulate its results. “They don’t know how it’s graded, what a result is supposed to look like or anything else about it,” avers Dr. Packer. “They don’t know how hard to try on it or how poorly they’re supposed to do on it, yet they can’t say ‘I don’t see anything,’ because that’s not plausible. It’s a subjective test, however, so a very sophisticated patient might be able to fake it, but most aren’t that sophisticated and won’t know how; they’ll get a score that’s either too good or too bad. Then, they’re caught. This is the general method for spotting a malingerer: Give him a test where a certain response would be physiologically impossible.”

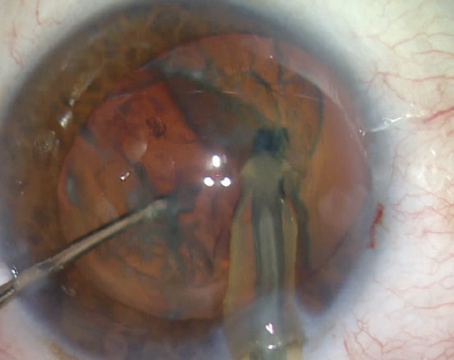

Surgeons say that the advent of certain instruments, such as the Pentacam, allows them to objectively evaluate a cataract’s density, which can help in cases such as this. “We do tests like the iTrace or HD Analyzer to look at the quality of the optical system,” says Jeffersonville, Indiana, surgeon Asim Piracha. “We use these to see if we can objectively confirm their complaints and say, ‘Yes, your vision is poor.’ If, however, these tests show a perfect optical system, I wouldn’t recommend surgery, because I don’t think the surgery would help them. We then get into why they’re not seeing well. Is it amblyopia? A retinal issue? An optic nerve problem? Often, we do a Pentacam exam and end up doing more testing than we’d normally do; we perform topography and an OCT of the optic nerve and retina to make sure it’s not something I’m missing on exam. If there aren’t any findings, however, they can complain but I can’t do cataract surgery because I’m not seeing any findings on exam that would justify it.”

|

Determining that a patient is feigning worse vision is only half the battle, however. The final challenge is informing him that you’re not going to perform surgery in such a way that you don’t incite anger or resentment. “When you return to the exam room with the patient, and have such things as his questionnaire, contrast sensitivity and the objective measurement of the cataract’s densitometry,” says Dr. Packer, “you can say, ‘Look, even though your visual acuity is in line with Medicare or your insurance carrier’s definition of a cataract, based on this additional testing you’re functioning pretty well. I don’t believe that cataract surgery’s benefits will outweigh the risks for you. Please come back and see me in a year.” He says framing it in this way gives you an argument to fall back on, rather than just pointing your finger at him and saying that he’s faking it.

Dr. Piracha says he’s seen patients seeking cataract surgery not because of malingering, but because of the effects of past corneal refractive surgery. “Some older patients come in and think, ‘I can’t see well, it must be a cataract,’ ” he says. “When I perform iTrace on these patients such as, for example, the post-RK patient who’s now hyperopic—+4 D and seeing maybe 20/30 best-corrected—and it shows the cornea isn’t right but the lens is pretty good, I tell them that cataract surgery probably won’t improve their quality of vision, it’ll just help reduce the hyperopia. Also, with the post-RK eye, cataract surgery’s not as predictable. I get patients referred in also, such as post-LASIK and post-RK, and they say they want cataract surgery. This testing helps me tell them that I don’t see a value in cataract surgery for them, since it’s not going to address their irregular astigmatism. If you perform cataract surgery on these patients, they can be difficult to deal with postop, because they expected cataract surgery to fix them but they still won’t see well.”

For surgeons who don’t have an iTrace, Dr. Piracha says the time-honored RGP over-refraction will tell you if the irregular vision is from the cornea or not. “If it’s an RK patient, or a patient with ectasia, and you do the RGP over-refraction and they go from 20/40 to 20/20,” Dr. Piracha says, “you know the problem is the cornea. If we do it, however, and they’re still 20/40, then we know the problem isn’t the cornea, because the RGP covers up the irregular astigmatism.”

When the Talk Turns Elective

Surgeons say that a few of these patients who are exaggerating their poor vision will actually be open to having an elective lens procedure when they’re eventually told that an insurance-paid cataract surgery isn’t advisable. Though this development may cause the surgeon to heave a sigh of relief—the patient isn’t going away mad and possibly embarrassed—experts remind that just because the patient is ready and willing to pay for the procedure doesn’t automatically mean that it should happen.

“We have to consider a few major things,” says Arturo Chayet, MD, of Tijuana, Mexico’s, Codet Vision Institute. “The first is the refractive error. In other words, myopes vs. hyperopes. There’s very strong data from the past 20 years that’s made it well-known that if a patient has an axial length of over 25 mm, and undergoes uneventful cat-aract surgery or refractive lens exchange, he’s in the highest incidence group for retinal detachment.

| Legal Lookouts | ||

|

“And, there’s the knowledge that high myopes are also at a higher risk for spontaneous bag dislocation 10 years after IOL implantation,” Dr. Chayet continues. “So these two issues, in my opinion, are definite exclusion criteria for RLE in high myopes.”

If a patient isn’t a candidate, Los Angeles ophthalmologist Sam Masket says the best thing is to be upfront and honest about it. “I always say that if it’s good for the patient, it’s good for the doctor—and the industry,” Dr. Masket says. “The patient’s interests must always be front and center.”

Dr. Chayet says that the patient’s age also plays a large role—especially which side of age 60 they’re on. “I’ve found that there’s a big difference between someone younger than 60, and someone older,” he says. “The crystalline lens becomes very dysfunctional after age 60. In my practice, most of the patients who request RLE start doing so at about age 52, right around the time they began wearing progressive lenses or using bifocals.” Dr. Chayet isn’t saying everyone should universally accept “dysfunctional lens syndrome” as a diagnostic term, but he is saying he thinks presbyopia is a precursor to cataracts. “I personally don’t do RLE on someone who’s younger than 60 and has 20/30 or better distance vision,” Dr. Chayet says. “I’ve found that the expectations of those patients are very high, and their satisfaction rate after RLE isn’t that good. Most of the very unsatisfied patients I’ve seen after RLE are these patients. Surgeons who perform RLE on them are pushing the envelope.

“Now, if the patient is older than 60, his distance vision is 20/40 or worse and the axial length is shorter than

25 mm, then I think the RLE conversation becomes more appropriate,” Dr. Chayet continues. “At that point, you have to explain to the patient what to expect and the side effects of our current IOLs, even if you go with monovision with monofocal IOLs. If the patient accepts the possibility of these side effects, then I feel comfortable doing the procedure.”

Dr. Chayet says categorizing patients based on their vision also helps ensure a positive outcome. “If the distance vision is good, I wouldn’t recommend doing any RLE,” he says. “On the other hand, if the patient is +4 D with 20/200 uncorrected distance vision with an anterior chamber depth of 2 mm or less, I think that patient might benefit from surgery. That’s because not only will he be able to see well, but the surgery will increase the depth of the anterior chamber, and will increase the angle, which will reduce the risk of glaucoma in the future. These types of patients, however, are the least frequently encountered ones seeking RLE these days.” He says the only refractive procedure he’d perform on a high myope would be a phakic intraocular lens in the form of the Visian ICL. “Even if I know cataract is a risk for them,” he says, “I’d rather implant an ICL [than perform RLE.]”

There are also the patients who aren’t malingering, but have visual issues that don’t reach the level of an insurance-covered cataract. Dr. Piracha offers as an example the patient who has a best-corrected vision of 20/25 or 20/30, and inquires about a refractive option. “This happens a good bit,” he says. “We rule out all the causes for decreased night vision, all the issues associated with glare and halo, and examine the ocular surface and topography to make sure nothing else is going on, and if they say they’d like to have refractive surgery, we’ll discuss it with them. If they don’t meet the definition of cataract per insurance—which here in Indiana is 20/50 or worse with either best-corrected vision testing or testing with glare—we tell them, ‘You have a mild cataract that doesn’t meet the official criteria yet, so you have two choices: Do an elective surgery now in order to get better vision without glasses, as well as improve your visual quality, or wait until you meet the criteria for insurance coverage, in which case we can see you back here in a year for another evaluation.’ I inform them that if they decide to wait, insurance will cover part of the procedure, but not the refractive-cataract surgery part—i.e., if they have astigmatism or want to see both near and far, then they’ll still need to pay for the laser AK, or a toric or multifocal lens.” He then follows this with a discussion of the risks outlined by Dr. Chayet, especially with regard to high myopes.

In the end, if a patient is trying to get surgery paid for but doesn’t really have a cataract, Dr. Packer says it often comes down to your estimate of his character, “as much as you can do that in the three minutes that you’re with him in the exam room,” he says. “Ask yourself, ‘Is this someone who’s primary motivation is refractive but he’s trying to frame it as a medical procedure?’ That’s the main distinction.” REVIEW

Dr. Piracha has spoken for iTrace in the past. The other surgeons have no financial interest in the products they discuss.