|

Mark B. Abelson, MD, |

Have you ever had a patient who didn't respond as expected to a prostaglandin analog, or someone who had an unusual degree of inflammation after cataract surgery even after you prescribed an appropriate anti-inflammatory? It may have been because of the patient's lack of compliance. Many patients are reluctant to admit to missed doses or trouble with medication instillation, which makes it more difficult to determine how compliant they are or why they're experiencing problems. In this article, we'll take a look at the main obstacles to compliance with eye drops, and steps that both industry and physicians are taking to overcome them.

Ways to Enhance Compliance

One study revealed that 69 percent of patients taking eye drops who experienced problems in drop administration would not admit this to their doctors, even if asked.1 Such reticence is a good reason for eye-care practitioners to provide every form of help possible during the patient's brief in-office time to facilitate compliance. Once a diagnosis has been made and the need for treatment established, the challenge of actually making sure the patient takes an ophthalmic medication involves more than meets the eye: First, we must help get the medication into patients' hands; second, they must remember to take it; third, they need to be able to successfully administer the eye drop; and finally, the overall process must be made as simple and convenient as possible.

Getting the Medication into Patients' Hands

Getting a patient to fill a prescription and purchase the needed ophthalmic drug can be a challenge in itself. It's important to educate the patient about the need for the medication and how to use it, and equally important to take the time to make sure the patient understands the handling, storage and administration of the drops as well as what results to expect. Using visual aids, fact sheets and other educational material can help improve compliance, as can ensuring patients receive information in their own language, if it's not English.

If patients understand that the prescribed medication is important or crucial to their health, this can help provide the motivation they need to fill the prescription. However, even this incentive may be stymied by prohibitive costs at the pharmacy counter. Health-care costs and formulary limitations often prove frustrating to patients and practitioners alike when attempting to acquire appropriate therapies. The role of the eye-care practitioner in maximizing compliance at this stage is to work with each patient's individual circumstances to determine which medication(s) will be most affordable for that individual, without compromising the efficacy of the medication or health outcomes for that patient. It may be possible to switch the patient to a lower-cost generic or reduce the number or frequency of drops. In addition, some low-income patients may be eligible for assistance programs through Medicare or the prescription savings program TogetherRx Access (togetherrxaccess.com), which is sponsored by a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Mental Blocks

Once the bottle of eye drops is in the patient's hands, he or she is still a long way from compliance. The next step is remembering to take the medication, since a bottle of unopened eye drops on the bathroom shelf will do nothing to improve the patient's condition. Unfortunately, in a disease such as glaucoma, the motivation to take drops may be low because the patient typically has no pain or other symptoms that would prompt adherence to a medication regimen.2

Many ocular conditions afflict the elderly, and deteriorating mental function and memory may affect adherence to medication regimens. This can be compounded by a complicated medication regimen that consists of many different treatments. A recent study of glaucoma patients showed that when a second glaucoma medication is added to an already existing monotherapy, the interval between patient refills significantly increases, indicating a decrease in compliance, which could affect how well IOP is being controlled.3

Younger ophthalmic patients, though they may be of sharper mental acuity, have other considerations such as busy work, school or travel schedules that can hurt their ability to take medication on a regular schedule.

In order to urge patients to follow a prescribed treatment regimen, patient education again plays a primary role. Giving patients a thorough understanding of the condition for which the medication is prescribed can make clear the vital importance of taking that medication. When patients know what they're working towards, it can sometimes provide enough motivation to make them remember to take their eye drops.

However, if this alone is not enough to foster compliance, there are other approaches. Tailoring a dosing regimen around a patient's regular schedule can help. There is good evidence that minimizing the frequency of dosing can result in increased compliance.4,5 Minimizing dose frequency can be particularly helpful to patients who are taking many medications every day.

|

| The Unidoser (Mystic Pharmaceuticals) uses a patient-replaceable cartridge system to deliver metered unit doses of ophthalmic medication to the ocular surface. |

Another tip for patients whose medication comes in unit-doses may be to store a portion of medication at several locations in their daily routine—at work, at home, in the car—so it's present wherever they are when dosing time arrives. The one consideration to be aware of with this practice is whether the drug has any storage requirements, such as temperature restrictions, that might lead to damage of the pharmacologically active component if the medication is left in a car in the hot summer sun.

|

| Allergan's Lumigan compliance aid features a light timed to flash and an optional audible alarm. |

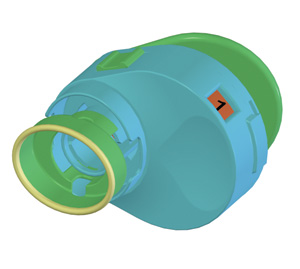

Compliance aids that help organize medication schedules may help provide needed structure. Written calendars or dosing schedules, such as those often used in clinical trial scenarios, may be enough of a cue to prompt patient adherence to an eye drop regimen. Beyond paper and pencil, some dose-organizing and administering devices, such as the Unidoser (Mystic Pharmaceuticals, Austin, Texas), are designed to separate and organize a multi-day supply of eye drops in unit-dose quantities. The Unidoser uses a refillable cartridge system, which contains multiple days' doses (see image at left). A dose number on the Unidoser cartridge, both visible and in Braille, makes it easy for patients to count how many doses they've taken and how many remain. A similar concept is used by some of the compliance aids to organize pills, like Dosett (Item Development, Stocksund, Sweden), which has four separate compartments for each day's medications.

Physical Considerations

The battle for compliance is still not over, even when a patient has remembered to take each dose. Simply opening an eye drop bottle can be prohibitively difficult for an arthritic or elderly patient. The small size of bottles, twist caps and stubborn safety seals require fine motor movements that can make it nearly impossible for these patients to open an eye drop bottle without assistance. Additionally, tipping back the head and positioning the dropper bottle over the eye complicates the administration process, particularly for the elderly or those with physical limitations.

The force required to squeeze out a drop can also be too great for some patients. Even if a patient is able to squeeze the bottle, aim can be compromised by the hand shaking with effort. In fact, aim is not just a problem for the elderly; studies show that many patients experience difficulty getting eye drops in the eye. One study found that up to 70 percent of patients could not properly instill an eye drop in the eye.6

Another study questioned 200 patients taking eye drops (ages 9 to 92) and found that 57 percent indicated that they had trouble administering drops. The most common reasons were directing the bottle (49 percent had occasional or frequent trouble with this) and squeezing it (20 percent had trouble with this).1 In the same study, a separate set of 30 patients in an eye surgery ward underwent testing for their ability to squeeze an eye drop bottle with sufficient force to instill an eye drop. Only six (20 percent) of these patients could do so on the first try.

Several currently available devices can help with these mechanical difficulties. One study has shown a modification as simple as changing the color of eye drop bottle tips to black can improve accuracy. The study evaluated subjects taking timolol, 88 percent of whom found the black-tipped bottles easier to use, and 68 percent of whom found they less frequently needed a second try to instill the eye drop.7

With regard to devices, the Unidoser not only stores the eye drops in unit-doses, but also doesn't require the head to be tipped back during drug administration and has an integrated eye cup to aid in aligning the device over the eye and holding the eye open for dosing.

Another emergent advance in therapy is a device that can turn medication into a mist rather than a drop, which is being developed by Optimyst Systems (West Islip, N.Y.). This may circumvent the squeamishness some patients have about taking eye drops.

Over-administration of drops can also become a problem when multiple tries are needed to deliver one drop to each eye. One study revealed that more than 37 percent of patients in a 141-patient study instilled more than two drops per eye, when the intent was to instill just one. In the same study, more than 20 percent of patients instilled more than three drops per eye.8 A more recent study found that patients reported obtaining a wide range of doses per bottle, from 26 to 110, when the actual number of doses per bottle ranged from 62 to 65.9 This type of patient mistake can be a serious source of medication error and compliance problems.

Despite the fact that strategies to aid compliance become more available and varied each year, the problem of compliance remains an insidious one. Since many patients are reluctant to admit non-compliance, whether intentional or not, to their eye-care practitioners, asking patients to instill their medication in your presence can be a good way to determine whether patients have difficulty with the bottle or the instillation process, and whether the right amount of medication is getting into the eye.

|

| The Optimyst system uses ultrasound to turn eye drops into an easy-to-administer mist. |

One new device, which attaches a microprocessor-controlled compliance monitor to eye drop bottles, may become a very helpful tool for identifying non-compliant patients in both clinical trial and clinical practice settings. This device contains sensors that measure temperature, force applied to the bottle, and vertical position of the bottle. It's been evaluated in two studies so far. In the first, it was shown to sense and record these parameters with at least 98-percent accuracy. (Ustundag C, et al. IOVS 2005;46:ARVO E-Abstract 4728)

In the second study, all 20 cataract patients on a specific medication regimen revealed non-compliance. The total number of drops over the 14-day evaluation period should have been 70, but the average actual dosage by patients was just 33 drops. (Hermann MM, et al. IOVS 2005;46:ARVO E-Abstract 3832) Though this device stops short of being able to determine whether the patient actually succeeds in getting the eye drop into the eye, it brings practitioners and researchers a step closer to knowing how much or how little real-world use of eye drops occurs. Such a monitor could significantly improve clinical trials by increasing the accuracy of compliance tracking in evaluations of drug efficacy, safety and tolerability. The device may also become a helpful tool in clinical practice to identify those patients for whom the practitioner should provide additional compliance aids.

We all have a role to play in the effort to improve compliance. Practitioners have a responsibility to educate the patient, but the responsibility does not end there. Even before drugs come to market, drug developers need to be aware of their role in compliance and make every effort to design eye drops that are comfortable and non-blurring, that do not cake, and that are easy to use. Working together, we are making progress toward the common goal of making it easier for patients to adhere to their medication regimen to achieve the best possible health outcomes.

Dr. Abelson, an associate clinical professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School and senior clinical scientist at Schepens Eye Research Institute, consults in ophthalmic pharmaceuticals. Dr. Torkildsen is in private practice in Andover, Mass., serves as a principal investigator for numerous studies, and consults in ophthalmic pharmaceuticals. Ms. Fink is a medical writer at ORA Clinical Research and Development in North Andover.

1. Winfield AJ, Jessiman D, Williams A, Esakowitz L. A study of the causes of non-compliance by patients prescribed eye drops. Br J Ophthalmol 1990;74:477-480.

2. Zimmerman TJ, Zalta AH. Facilitating patient compliance in glaucoma therapy. Surv Ophthalmol 1983;28(Suppl):252-258.

3. Robin AL, Covert D. Does adjunctive glaucoma therapy affect adherence to the initial primary therapy? Ophthalmology 2005;112:5:863-868.

4. Richter A, Anton SE, Koch P, Dennett SL. The impact of reducing dose frequency on health outcomes. Clin Ther 2003;25:8:2307-2335.

5. Patel SC, Spaeth GL. Compliance in patients prescribed eye drops for glaucoma. Ophthalmic Surg 1995;26:3:233-236.

6. Brown MM, Brown GC, Spaeth GL. Improper topical self-administration of ocular medication among patients with glaucoma. Can J Ophthalmology 1984;19:2-5.

7. Stack RR, McKellar MJ. Black eye drop bottle tips improve compliance. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2004;32:1:39-41.

8. Kass MA, et al. Part I. Patient administration of eye drops: Interview. Ann Ophthalmol 1982;14:775-779.

9. Winters JE, Castells DD, Lesher GA. Variability in doses obtained from a multi-dose ophthalmic solution: A potential source of error in the assessment of compliance. Optometry;72:3:185-8.