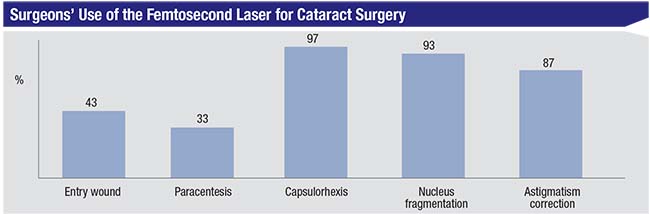

Surgeons’ use of femtosecond lasers is just one aspect of this month’s e-survey. This month, 997 surgeons of the 7,564 who received the survey opened it (13.2 percent open rate) and, of those, 83 fully completed the survey. To compare your practice pattern with theirs, read on.

Friends of Femto

As mentioned earlier, the percentages of surgeons who use/don’t use a femtosecond

|

Chicago surgeon Jonathan B. Rubenstein, MD, says he appreciates what the femto brings to his practice. “It decreases phaco energy, phaco time and turbulence during the phaco portion,” he says. “It’s especially good in dense cataracts and patients with endothelial compromise.”

Lisa K. Feulner, MD, PhD, from Bel Air, Maryland says, “I find that the femto laser provides clean, accurate, and reliable LRIs, entry wound incisions and paracenteses. The paracentesis is well centered in the bag which, I believe, allows for symmetric fibrosis of the capsule over time, and therefore reduces rotation and tilting of the IOLs. Nucleus fragmentation with the femto reduces the phaco time and energy and is gentler on the cornea.”

|

Christian Klein, MD, of Rochester, New York, says that using the femto has highlighted some pros and cons for him. “I like the size and centration of the capsulorhexis,” he says, “but I dislike the following: the added time; the fact that it requires reliable and expert technical support which is not always available; the frequent pupil miosis that makes an otherwise routine case become unnecessarily more complex (or expensive if I then have to add Omidria to the bag); the difficulty in seeing the fluid wave in hydrodissection when using the ‘waffle pattern’ [for nuclear segmentation]; and it’s sometimes more difficult to remove cortex. Frankly, I think it offers minimal improvement for the added time burden and increased chances of the above-mentioned issues occurring intraoperatively in our particular setting (a university).”

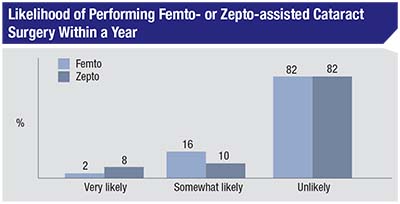

Though a number of surgeons use the femto, as in previous years, a large proportion, 82 percent, say they’re unlikely to take up the femto or the new Zepto capsulotomy device for use in their surgeries. Eight percent say they’re “very likely” to use the Zepto in the coming year (vs. 2 percent who say the same for the femto), though 16 percent say they’re “somewhat likely” to use the femto vs. 10 percent who are somewhat likely to try the Zepto.

“There’s no significant benefit to patient outcome but an increased out-of-pocket cost to the patient,” avers Gregory Cox, MD, of Hamilton, New Jersey, in reference to the femtosecond laser.

Robert Mobley, MD, of Clinton Township, Michigan, says he’s unlikely to try the new technology, due to benefit/cost issues. “I don’t find any real advantage to femto,” he says. “Plus, it takes up time and is an unnecessary cost to the patient. I also found the integrity of the capsulorhexis to not be as good as manual, in my limited experience. I’m not familiar with Zepto, however.”

|

Some surgeons, however, see some potential in the technologies, and are willing to try them down the road. “Zepto may be safer for white cataracts,” says a surgeon from Wisconsin. Another surgeon says he’s somewhat likely to try the technology due to a “new practice opportunity coming up.”

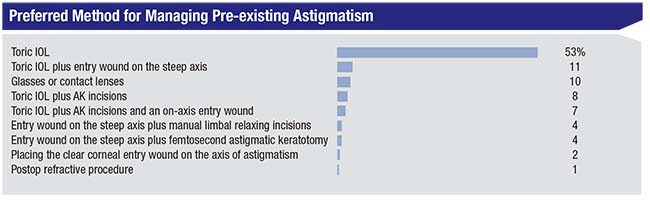

Astigmatism Management

Surgeons also weighed in on their preferred method for managing astigmatism in cataract patients.

|

Similar to previous years, the use of a toric intraocular lens was the most popular option, at 53 percent. The second option was a toric IOL combined with placing the entry wound on the steep axis (11 percent). The range of options chosen appear in the graph above.

With regard to toric lenses, Dr. Mobley says, “They’re very reliable and stable over time for >1 D of corneal astigmatism. I do astigmatic keratotomy for lower levels of astigmatism.” Ligaya Prystowsky, MD, of Nutley, New Jersey, prefers toric lenses in most cases, but keeps her options open. “I have confidence in the toric lenses but they are limited, so I initially enter in the steep axis and add sutures if needed with a toric IOL,” she says. “I have been able to have residual astigmatism of only -1.50 D from a preop value of -6 D. The patients are happy. I find the level of astigmatic correction is limited to -2 D max with sutures alone.”

A surgeon from West Virginia uses toric lenses plus the entry incision on the steep axis. “This approach is reliable and not dependent upon patient healing,” he says, “which is a variable I care to eliminate.” Sean Lalin, MD, of Morristown, New Jersey, combines a toric IOL with femtosecond laser astigmatic keratotomy, and describes his approach: “I use the femto to address up to 1.25 D of astigmatism, but use a combination of a toric lens and femto for higher degrees of astimatism,” he says, “especially with multifocal lenses where my goal is to reduce the residual astigmatism to less than 0.5 D.”

A surgeon from Texas combines the cataract wound with the femtosecond. “I use both entry wound on the steep axis plus femtosecond astigmatic keratotomy on patients with less than 1 D of astigmatism,” he says. “For those patients with greater than 1 D of astigmatism, I will put in a toric IOL. These are the best ways to eliminate or reduce astigmatism in my hands.”

Other Topics

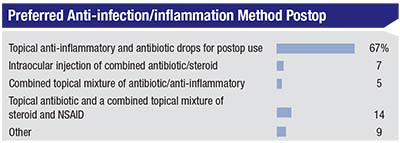

Surgeons also shared their views on other aspects of surgery:

• Intraoperative aberrometry. The use of wavefront sensing in order to hone the selectio

|

“It helps with long/short eyes and multifocal and torics,” says John Fitz, MD, of Farmington, Missouri. “Sometimes, though, it gives results that do not make sense—and you then go with preop plan.” Audrey Rostov, MD, of Seattle feels similarly, saying, “It’s helpful but doesn’t capture on some difficult cases where it could benefit most.”

“It’s great for post-LASIK and abnormal eyes but time-consuming,” says Dr. Lalin. Ismail A. Shalaby, MD, of Baltimore says the technology is useful but can pose some logistical problems. “Benefits: More accurate IOL selection,” he says. “Shortcomings: It takes extra time, and you need a lot of IOLs in stock for it to be useful.”

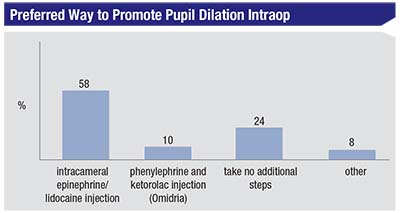

• Managing miosis. When faced with a pupil that won’t cooperate, the option chosen by most surgeons on the survey is a homemade combination of intracameral epinephrine/lidocaine injection, chosen by 58 percent. Twenty-four percent take no additional steps. The results from this question appear in the graph on page 46.

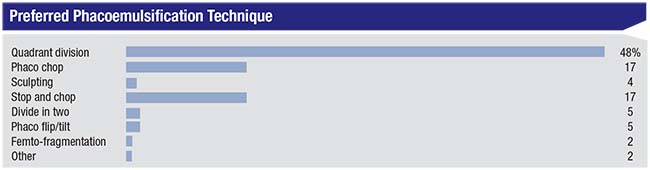

• Nucleo-fracture preferences. The most popular option on the survey was quadrant division, chosen by 48 percent of the surgeons. Tied for second place are phaco chop, and stop and chop, each at 17 percent.

Dr. Prystowsky prefers quadrant division. “I combine with initial debulking in the center, then quadrant division, and chopping later as the pieces come depending on the density of the lens,” she says. “I have a population with very dense lenses and fear of surgery is prevalent.”

A surgeon who prefers to do phaco chop says of the technique: “Phaco chop is less time-consuming, uses less phaco energy, is safer than sculpting techniques and is better in cases of zonular weakness.”

Christopher Ketche

|

Surgical Tips

The respondents also took the opportunity to share surgical pearls:

Keith Skolnick, MD, Plantation, Florida has advice for proper IOL injection. “Since the 2.4-mm wound is tight, inject the IOL in a planar fashion parallel to the iris,” he says. “If you angle the injector you’re less likely to be able to go through smaller incisions.”

John J. Brozetti, MD, Johnstown, Pennsylvania, advises, “Don’t proceed with the case unless the pupil is 5 mm or larger,” he says. “Use intracameral shugarcaine +/- pupil stretching for inadequate pupil size for every case.”

Dr. Klein has advice for breaking up the nucleus. “While I will still do a “primary” chop at the start of phacoemulsification for some cases, I’ve begun to sculpt a bowl more frequently at the start of nuclear dissembly,” he says. “This really improves the ability to get the phaco tip deeper into the nuclear wall and makes getting a successful chop much more reproducible.”

Dr. Fitz says simplification is one of the keys to success. “Try to maintain the KISS principle: keep it simple, stupid,” he says. “And, don’t overpromise. Some of these innovations are more trouble than they are worth; I’m frustrated that ORA and femto slow things down, and getting people to spend extra is hard and raises expectations, so don’t push hard.”

James E. Lusk, MD, Shreveport, Louisiana, advises surgeons to “Release fluid/viscoelastic simultaneously using the heel of the angled cannula during hydrodissection to assure elevation of the lens in the capsule bag to attain the ability to rotate the nucleus. The rest of the case goes routinely.”

Dr. Rubenstein says it can help to customize your approach. “Use three different methods in conventional phaco: 1) stop and chop for dense lenses; 2) split and swirl for medium lenses; 3) bowl and roll for soft lenses.”

Rather than giving nuts-and-bolts advice, some surgeons gave more qualitative tips to mull over:

• “Fast is slow; smooth is fast,” says a surgeon from Dallas.

• “Stay focused,” says a California surgeon.

• “Enjoy yourself in the OR,” says Ron Glassman, MD, of Teaneck, New Jersey

• “Perfect is the enemy of good,” says Robert Mahanti, MD, of Flagstaff, Arizona.

Dr. Ketcherside says it’s always good to learn various pearls, but then, “Find what works for you, and get really good at that,” he says. “Know that you’ll have to refine as you go, but also that there’s no ‘one right way.’ ” REVIEW