|

| Image courtesy of Getty Images. |

Telehealth in eye care has historically followed the “store-and-forward” model, wherein retinal photography is combined with remote interpretation for screening of ophthalmic diseases, such as diabetic retinopathy and retinopathy of prematurity, but is otherwise less useful than in some other medical fields. Did the pandemic experience change that in any way, positive or otherwise? A recent study published in JAMA Ophthalmology compared telehealth trends between different medical specialties and ophthalmic subspecialties at a major academic institution over 18 months, beginning at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. In April 2020, a hybrid model of care delivery was implemented wherein asynchronous data could be collected to enhance telehealth consultation with clinicians.

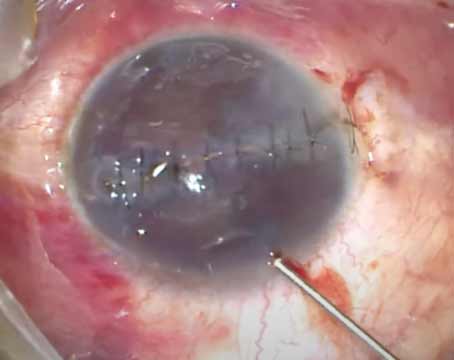

The hybrid model of augmented telehealth in the study increased the depth of remote evaluation across several subspecialties. On the other hand, its highest users were subspecialties that had lower telehealth adoption and are known to be less amenable to virtual practice (e.g., cornea and glaucoma). Asynchronous testing data from this program changed management in 25.4 percent of encounters and expanded telehealth use to new indications, including the postoperative assessment of corneal transplantation.1

The study’s authors say that the use of asynchronous testing may help telehealth be more feasible in subspecialties such as retina and glaucoma, the exams of which are traditionally difficult to perform remotely.

“Physician participation in the hybrid telehealth model was voluntary so we tried not to draw absolute conclusions on its relative utility between subspecialties,” the authors note in an e-mail comment to Review. “Nonetheless, combining asynchronous testing with telehealth enabled the evaluation of certain conditions which conventionally had not been cared for remotely, highlighting new opportunities that lie ahead. Our work suggests that the hybrid model will be useful for most if not all subspecialties, and we suspect the degree will be correlated with the quality and range of data acquired.”

The asynchronous data in the hybrid model included visual acuity, intraocular pressure measurement, pachymetry, visual field testing, OCT (macula or optic nerve), retinal photography, specular microscopy and slit lamp photography. The overall quality improvement study evaluated retrospective, longitudinal, observational data from the first 18 months of the COVID-19 pandemic (January 1, 2020, through July 31, 2021) for 881,080 patients receiving care from outpatient primary care, cardiology, neurology, gastroenterology, surgery, neurosurgery, urology, orthopedic surgery, otolaryngology, obstetrics/gynecology and ophthalmology.

The volume of in-person outpatient visits dropped by 83.3 percent (39,488 of 47,390) across the evaluated specialties at the onset of shelter-in-place orders for the COVID-19 pandemic, and the initial use of telehealth increased for these specialties before stabilizing over the 18-month study period. The highest use was found in gastroenterology, urology, neurosurgery and neurology, and the lowest use was in ophthalmology.

Asynchronous testing was combined with 126 teleophthalmology encounters, resulting in change of clinical management for 32 patients (25.4 percent) and no change for 91 (72.2 percent). In ophthalmology, telehealth use peaked at 31 percent encounters early in the pandemic and returned to mostly in-person visits as COVID-19 restrictions were lessened. After the stay-at-home orders were lifted, ophthalmic use of telemedicine (1.1 percent) returned almost entirely to pre-pandemic levels, while other specialties continued to provide a considerable percentage of visits remotely (14.9 percent to 65.9 percent).

“Clinical decision making in ophthalmology relies heavily on examination and testing, which are typically acquired in-person and pose intrinsic barriers for telehealth,” the authors state. “An important takeaway from our study was that asynchronous testing did make telehealth evaluation feasible in many cases, and one approach for overcoming these barriers.”

Consistently, oculoplastics and pediatric ophthalmology, which often rely on external examination of the eye, had the greatest telehealth use during the COVID-19 shelter-in-place orders and, interestingly, maintained some level of telehealth even after the orders were lifted. However, these two specialities didn’t use the asynchronous model, which suggested a relative reliance on external video examination. In contrast, the retina, glaucoma and cornea subspecialties, which rely more heavily on microscopic examinations and specialized tools to evaluate ocular health and anatomy, didn’t employ telehealth services as often.

“Telehealth use by ophthalmology was modest compared with other specialties, and patient care returned almost entirely to in-person settings by October 2020,” the researchers noted in their paper.1

An interesting finding in the study is that separating testing from clinical examination could potentially help with clinic workflow.

“Telehealth has the potential to improve access to care as well as workflow efficiency,” the authors say. “Clinic visits are often prolonged due to the need of specialized testing. Separating testing from the clinical visit creates opportunities to streamline workflow and wait times. Additionally, remote testing can be used to reach remote areas and expand the reach of ophthalmic care.”

A commentary by Wilmer Eye Institute retina specialist David Glasser, also published in JAMA Ophthalmology, emphasized that the most important reason for the lag in ophthalmology’s adoption of telehealth during the COVID-19 public health emergency perhaps lay in the visual nature of its practitioners’ work. “Literally seeing the pathology is integral to our evaluation and management decisions to a greater degree than in most other specialties,” writes Dr. Glasser. “The techniques and devices used to facilitate visualization are not easily transferable to a remote visit.”2

Once clinicians developed protocols to reduce the risk of person-to-person spread, the author noted that hybrid systems gave way to the greater efficiency of same-day in-person testing and visits.2

“There are potential technological solutions to these limitations, offering the promise of access to care to remote and disadvantaged populations but only if the industry can realize a return on investment in developing new technology and healthcare professionals can use the resulting devices without incurring financial penalties,” Dr. Glasser states.2

Though the study’s findings are no doubt interesting, the authors acknowledge that it has some limitations. “A limitation of our study is that it was not designed to evaluate the long-term potential of teleophthalmology,” they say. “Asynchronous testing was performed in the same buildings as in-person appointments, and it was more convenient for our department to return to in-person visits once COVID-19 restrictions were lifted. Use of remote testing sites will be a better approach for assessing whether the hybrid model is feasible long-term.”

The authors say that they plan to continue to study the topic of telehealth in ophthalmology. “We hope to study the prospective sustainability of this new model of care from a financial and logistical standpoint,” the say. “It will also be critical to further study and learn about the blind-spots associated with telemedicine, since we certainly don’t want to cause harm by missing disease.”

1. Mosenia A, Li P, Seefeldt R, et al. Longitudinal use of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic and utility of asynchronous testing for subspecialty-level ophthalmic care. JAMA Ophthalmol. December 1, 2022. [Epub ahead of print].

2. Glasser DB. Is there a future for telehealth in ophthalmology? JAMA Ophthalmol. December 1, 2022. [Epub ahead of print].

Industry newsCord Files for Premarket Approval for New Intraocular Lens Cord, a privately held ophthalmic medical device company, recently announced that it’s submitted a Premarket Approval application to the FDA for its Model SC9 Intraocular Lens. The SC9 lens was designed to provide a monofocal spherical optic but has a rigid structure to “consistently locate the optic in a position intended to provide intermediate vision that is superior to that of a standard monofocal IOL,” Cord says.

Oxurion to Continue KALAHARI Phase IIb Study in DME Oxurion announced an Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC) recommended continuation of the company’s KALAHARI Phase II, Part B clinical trial evaluating Oxurion’s investigational treatment for diabetic macular edema.

Ocuphire Pharma Submits Nyxol NDA to FDA Ocuphire Pharma recently announced the submission of a New Drug Application to the FDA for phentolamine ophthalmic solution 0.75% (Nyxol) for the reversal of pharmacologically-induced mydriasis. |

First Dose of COVID Vaccine May Cause Uveitis to Flare

A recent study demonstrated an increased risk of uveitis flare following COVID vaccination. This risk was highest among those with previous recurrence, chronic uveitis and a shorter period of quiescence.

The retrospective study identified participants from the Inflammatory Eye Disease Registry at Auckland District Health Board who were diagnosed with uveitis between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2020. The date of COVID vaccination was determined from the patient’s clinical record, and the rate of flare was calculated for three months prior to vaccination and for three months after each vaccination. Uveitis flare was defined as the presence of new or increased uveitis activity that required a change in treatment.

A total of 4,184 eyes of 3,008 patients were included, with a total of 8,474 vaccinations given during the study period. The median age was 54.8 years, and 1,474 (49 percent) of the participants were female.

Noninfectious etiology was most common, occurring in 2,296 patients (76.3 percent), with infectious etiology in 712 (23.7 percent). The rate of uveitis flare was 12.3 per 1,000 patient months at baseline, 20.7 after the first dose, 15 after the second, 12.8 after the third and 23.9 after the fourth. The median period of quiescence prior to flare was 3.9 years. An increase in uveitis flare was seen both in infectious uveitis (13.1 at baseline compared with 20.2 after first dose) and noninfectious uveitis (12.4 at baseline compared with 20.9 after first dose).

Risk factors for uveitis flare were identified to be recurrent uveitis, chronic uveitis, a shorter period of quiescence and the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Median time to uveitis flare was 0.53 months following the first vaccination, 1.74 months following the second and 1.35 months following the third.”

Jordan CA, Townend S, Allen N, et al. Navigating COVID-19 vaccination and uveitis: identifying the rates and risk of recurrent uveitis following COVID vaccination. Ophthalmology. December 16, 2022. [Epub ahead of print].

New Research Breaks Down Central Serous Chorioetinopathy

Previously, central serous chorioretinopathy has been classified as either acute or chronic depending on disease duration, but thresholds vary from study to study. A recent alternative classification system categorizes the disease as either simple or complex based on whether the retinal pigment epithelium alteration region is greater than two disc areas. A third atypical type of CSC was classified to include bullous variant, RPE tear and association with other retinal diseases. A team of researchers used the revised system in a new study to investigate the clinical and genetic characteristics of simple vs. complex CSC.

The study evaluated 319 patients with idiopathic CSC. Disease type was determined based on the presence or absence of retinal pigment alterations greater than two disc areas in either eye. Among the cohort, 53 patients (16.6 percent) had the complex type, which was seen exclusively in males (100 percent), and most of the patients with the simple type were also male (79 percent).

The team also found that compared with patients with the simple type, those with the complex type had a significantly higher proportion of bilateral involvement and descending tract(s). Complex CSC patients also had a thicker choroid (425 µm vs. 382 µm) and thinner central retina (274 µm vs. 337 µm) compared with simple CSC patients.

The study also genotyped CFH variants rs800292 and rs1329428. The researchers reported that the “risk allele frequencies of both variants were significantly higher in the complex vs. simple type.”

The researchers say, “The risk allele of the CFH gene is associated with an RPE alteration greater than a two-disc area, including patchy atrophy and descending tract(s). Although this study was cross-sectional, genotyping these variants might be useful for predicting RPE atrophy development and enlargement.”

Yoneyama S, Fukui A, Sakurada Y, et al. Distinct characteristics of simple versus complex central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. December 7, 2022. [Epub ahead of print].