When you’re faced with a patient who lacks capsular support, your options for intraocular lens fixation include anterior chamber IOLs and iris- or scleral-fixated posterior chamber IOLs; you may also decide to leave the patient aphakic and refer the case. Whichever you choose, experts say it should be the option you’re most comfortable with. In this article, two veteran surgeons who moderate a course managing eyes with an absence of capsular support at the American Academy of Ophthalmology meeting compare the current methods for secondary IOL implantation and offer advice for achieving successful outcomes in these tricky cases.

The Learning Curve

IOL implantation in the absence of capsular support isn’t a common procedure, and the dearth of cases to practice on makes it difficult to build up a robust skillset.

Finding a mentor who’s well-versed in the technique you want to learn will provide you with valuable insights and experiences. “Every surgery has so many nuances,” says Mark Gorovoy, MD, of Gorovoy MD Eye Specialists in Fort Myers, Florida. “If you’re just watching videos, you’ll miss a lot of those nuances. It really pays to find a mentor who can talk you through the procedure.”

Sadeer B. Hannush, MD, a professor of ophthalmology at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University and attending surgeon on the Cornea Service at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia, recommends that surgeons learning these fixation methods familiarize themselves with one technique first and do it over and over again until they become comfortable with it and proficient in the use of the technique.

“Don’t try to be a Jack-of-all-trades,” he says. “Most surgeons won’t have enough of these cases to do them on a regular basis. There are very few of us who do. After more than 30 years in practice and with a referral base of more than 100 ophthalmologists, I still do no more than one or two a week. I don’t think I’ve ever had a year with more than 100 of these cases. There just aren’t that many out there. Because a comprehensive ophthalmologist doing this kind of work may have only one or two cases per year, picking a technique they’re comfortable with is key. Otherwise, they should refer these cases out.”

Knowing your strengths and weaknesses will ultimately benefit you. “If the lens migrates posteriorly, for example, you may have to refer it to someone who’s comfortable fishing it out and taking over the case,” Dr. Hannush says. “If you have access to a retinal colleague who can join you on the case, they can do the pars plana vitrectomy and float the implant up for you into a location you can reach it.”

Anterior Chamber Fixation

The anterior chamber can hold an IOL, but surgeons note that it isn’t an ideal location for an implant, given such close proximity to the cornea. The innovation of the flexible open-loop anterior chamber IOL has led to less inflammation in the angle than its predecessor, the rigid closed-loop AC IOL, but these lenses—even when properly placed—may lead to long-term complications such as endothelial decompensation, chronic inflammation, uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema (UGH) syndrome or cystoid macular edema. Additionally, because most AC IOLs are made of polymethylmethacrylate, they aren’t foldable and require a scleral tunnel or a large, typically 6-mm corneal incision for insertion, which may induce astigmatism.

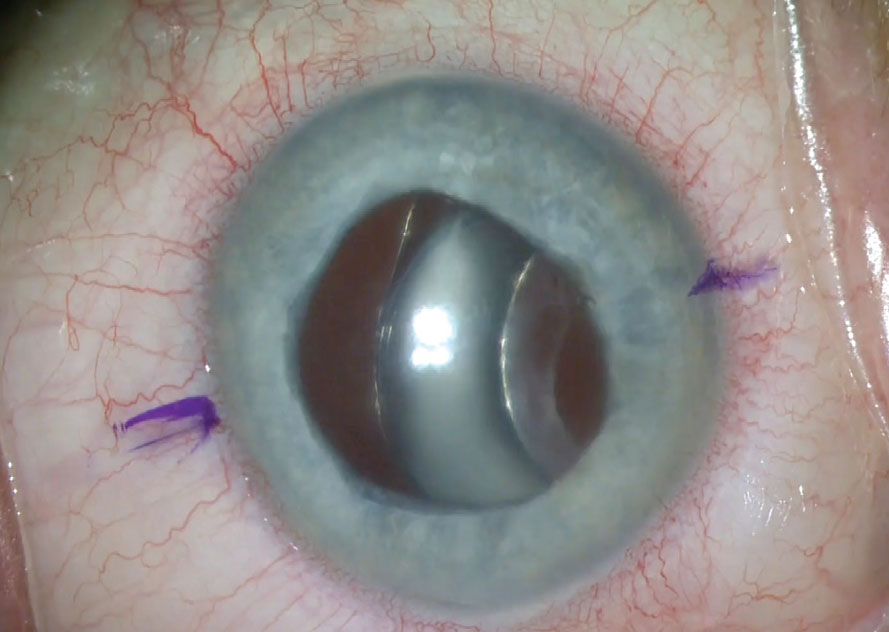

|

|

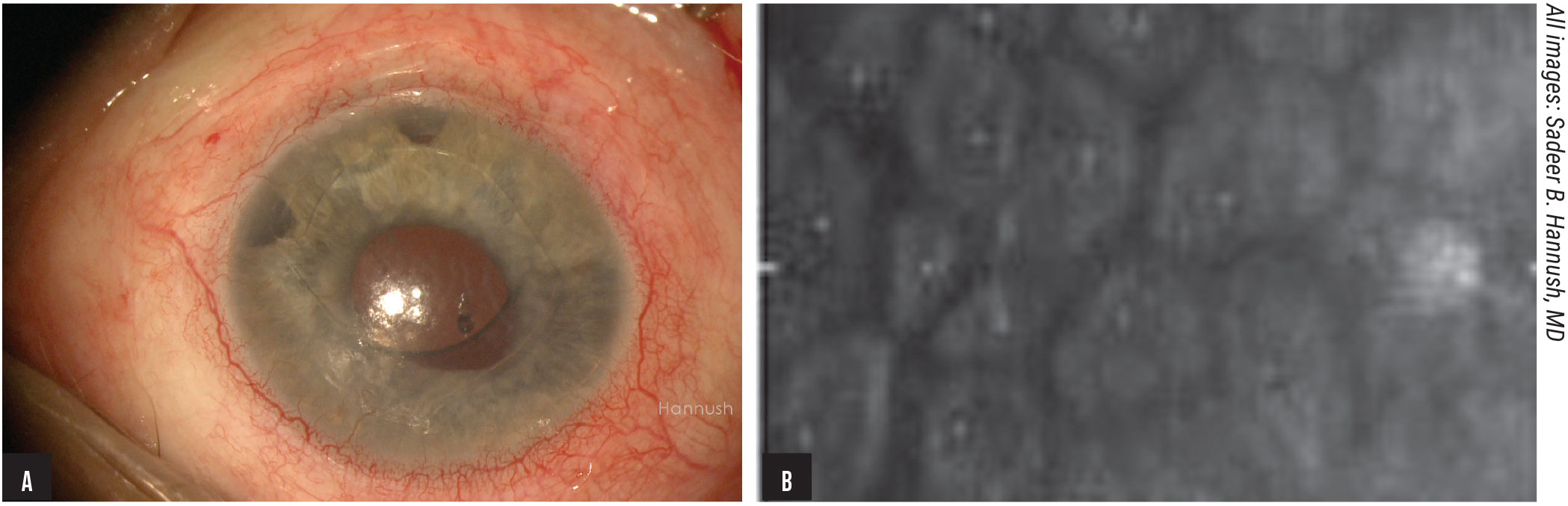

Figure 1. Ovalization of the pupil secondary to iris tuck is a potential complication of AC IOLs (A). This same patient also had a low endothelial cell count with pleomorphism and polymegathism (B). Click image to enlarge. |

Though a retrospective analysis comparing AC IOLs to sutured PC IOLs found no statistically significant difference in BCVA outcomes or complications,1 Dr. Gorovoy says he’s adamant that no one receive an AC IOL today. “The angle isn’t a place for a foreign body with micromovement,” he says. “We’ve seen this over and over again. It’s a relatively simple procedure if there’s enough iris to support the anterior chamber lens, but there are too many issues with these implants.”

Dr. Hannush almost always avoids AC IOLs, preferring scleral fixation of PC IOLs. “AC IOLs are a setup for chronic inflammation, glaucoma and corneal endothelial damage,” he adds. “That being said, you shouldn’t write them off completely. If the surgeon is most comfortable implanting an AC IOL and doesn’t have access to a surgeon skilled in scleral fixation, then an AC IOL may be an option, albeit not ideal, and the patient may benefit from this lens—at least in the short term. You should do what’s best for the patient in your hands.”

Here are some things to keep in mind when performing anterior chamber IOL placement:

• Consider the patient’s age. Dr. Hannush says that some patients may do well with an AC IOL in the short term, especially if they’re older. “Those with a limited life expectancy can be visually rehabilitated with an AC IOL, possibly for the rest of their remaining days,” he says. “In my hands, the only scenario in which I might find it reasonable to implant an AC IOL is in an older (90 to 95 years), monocular patient with an intact anterior hyaloid face, an open angle 360 degrees around, and for whom I wouldn’t want to extend the surgical time because of the increased risk of bleeding or other intraoperative complications. That same patient may also benefit from aphakic glasses or a contact lens.”

• Select the appropriate-sized lens. A properly sized AC IOL is based on the white-to-white measurement. However, every patient’s limbal anatomy is different, resulting in significant variations in AC IOL size estimates.2

“There’s no one-size-fits-all AC IOL,” says Dr. Hannush. “An undersized implant will propel in the anterior chamber, and an oversized AC IOL will vault anteriorly and/or the haptics will dig into the iris or ciliary body. Very few surgery centers keep AC IOLs of various sizes on consignment anymore—most of the ones available to the surgeon are all the same size.”

• Ensure that the haptics are positioned correctly. “The four haptics of the flexible open-loop lens should end up on the scleral spur,” Dr. Hannush says. “If you’re able to do intraoperative gonioscopy, that would be ideal.”

Iris Fixation

In the United States, surgeons perform retropupillary iris fixation of a three-piece PC IOL. This method has the advantage of placing the IOL closer to the nodal point and rotational axis of the eye than an AC IOL.3

Abroad, anterior chamber iris-clawed or -clipped implants such as the Artisan lens (Ophtec) have been in use for decades but were never made available in the United States in powers for use in aphakic eyes. (The version of the iris-claw lens that is available in the U.S. comes in only very high negative powers [e.g., -12 D or -14 D] and is meant for phakic patients with high myopia.) These lenses are inserted through an approximately 5-mm incision, and the iris is “clipped” to the implant by drawing tissue between the claws with an enclavation needle.

“One of the nice things about the retropupillary iris fixation technique is that you can put a foldable lens through a small incision,” says Dr. Hannush. “It’s also less involved than sclerally fixating an implant. You place the lens behind the iris and pass a 10-0 polypropylene suture to imbricate the haptics into the iris. There’s a potential complication of chronic inflammation when you suture an implant to a uveal structure, especially in the presence of iridodonesis, however. For this reason, I don’t favor iris fixation.”

|

|

Figure 1C. The same patient (seen in Figures 1A and B) also had marked cystoid macular edema associated with the AC IOL in the left eye. Click image to enlarge. |

Dr. Gorovoy agrees. “I don’t think iris-supported lenses are quite as potentially injurious to the anterior segment and eye in general as AC IOLs, but I don’t do iris-sutured IOLs. The iris isn’t the best place to be hanging any hardware.” Other complications of iris fixation include UGH syndrome and pigment dispersion from rubbing on the implant.

When performing iris-sutured fixation, surgeons say pupil anatomy and technique are key. “A good candidate for this procedure is a patient who’s aphakic, or has been rendered aphakic by complicated cataract surgery, but has a nice, round pupil,” Dr. Hannush says. “You can suture a lens on the back surface of the iris if you have no qualms about doing that. You can avoid ovalizing the pupil by suturing the haptics of the implant as peripherally as you’re comfortable with.”

Sutured Scleral Fixation

“Securing an implant to the scleral wall is a very effective—and my preferred—technique,” says Dr. Hannush. While it’s more involved than anterior chamber or iris fixation, many surgeons consider it to be the procedure of choice—with proper training.

In general, posterior chamber implants are preferable since they approximate the position of the natural lens and are less likely than anterior chamber implants to result in corneal decompensation over time. But scleral-fixated implants also have the advantage of being suitable for almost all patients who need a secondary IOL.

“Any patient who’s going to get a secondary IOL and has no capsular support is a good candidate for scleral fixation,” Dr. Gorovoy says. “That’s the nice part of it—every eye has a sclera. We don’t depend on the iris or the angle.”

“We used to use 10-0 polypropylene suture, but that may have been too fine a suture; it would sometimes break or cheesewire after 10 to 15 years, leading to dislocated lenses,” Dr. Hannush says. “More recently we’ve been using 8-0 Gore-Tex or 9-0 polypropylene because they’re more durable.”

When considering whether to suture an implant to the sclera or not, surgeons recommend keeping the following in mind:

• For certain patients, keep the procedure short. “If a patient has multiple risk factors for suprachoroidal effusion or hemorrhage, such as hypertension, peripheral vascular disease or glaucoma, or if the patient is on blood thinners and can’t stop them, then I wouldn’t want to extend the procedure to sclerally fixate a PC IOL,” Dr. Hannush says. “I also wouldn’t make a large incision to implant a one-piece PMMA IOL, for all the obvious reasons.”

• Select the appropriate lens. Dr. Hannush says the best lenses for suturing to the sclera are one-piece PMMA lenses with eyelets on the haptics like the CZ70 BD (Alcon). “The foldable lenses don’t have eyelets on them, but you can still suture a foldable lens,” he notes.

Some surgeons have used the three-piece hydrophobic acrylic MA60AC or MA50BM (Alcon) or AR40 or ZA9003 (J&J Vision), the hydrophilic acrylic Akreos AO60 (Bausch + Lomb), the one-piece hydrophobic acrylic enVista MX60 (Bausch + Lomb) or the hydrophobic acrylic CT Lucia 602 (Zeiss). The last lens has polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) monofilament haptics, whose strength makes them ideal for intrascleral haptic fixation, although not necessarily for suture fixation, some surgeons say. “Three-piece IOLs are better suited for ISHF than for scleral suturing,” says Dr. Hannush.

• Bury your knots. Suture knot erosion is easily avoided by burying the knot. “You don’t want a knot on the surface, especially if you’re using 8-0 Gore-Tex,” says Dr. Hannush. “If using 9-0 or 10-0 polypropylene, you can leave a knot on the surface of the sclera as long as the rabbit ears of the knot are long and can be tucked under conjunctiva. If the suture ends are short, they’ll erode through the conjunctiva and out of the eye, and then you’ll have direct communication between the ocular surface and the inside of the eye, which puts the patient at risk for endophthalmitis.”

Sutureless Scleral Fixation

Many surgeons have now adopted sutureless scleral fixation methods. Currently, the two most popular ways to secure a posterior chamber implant to the sclera without sutures are the glued IOL technique and the Yamane technique.

|

|

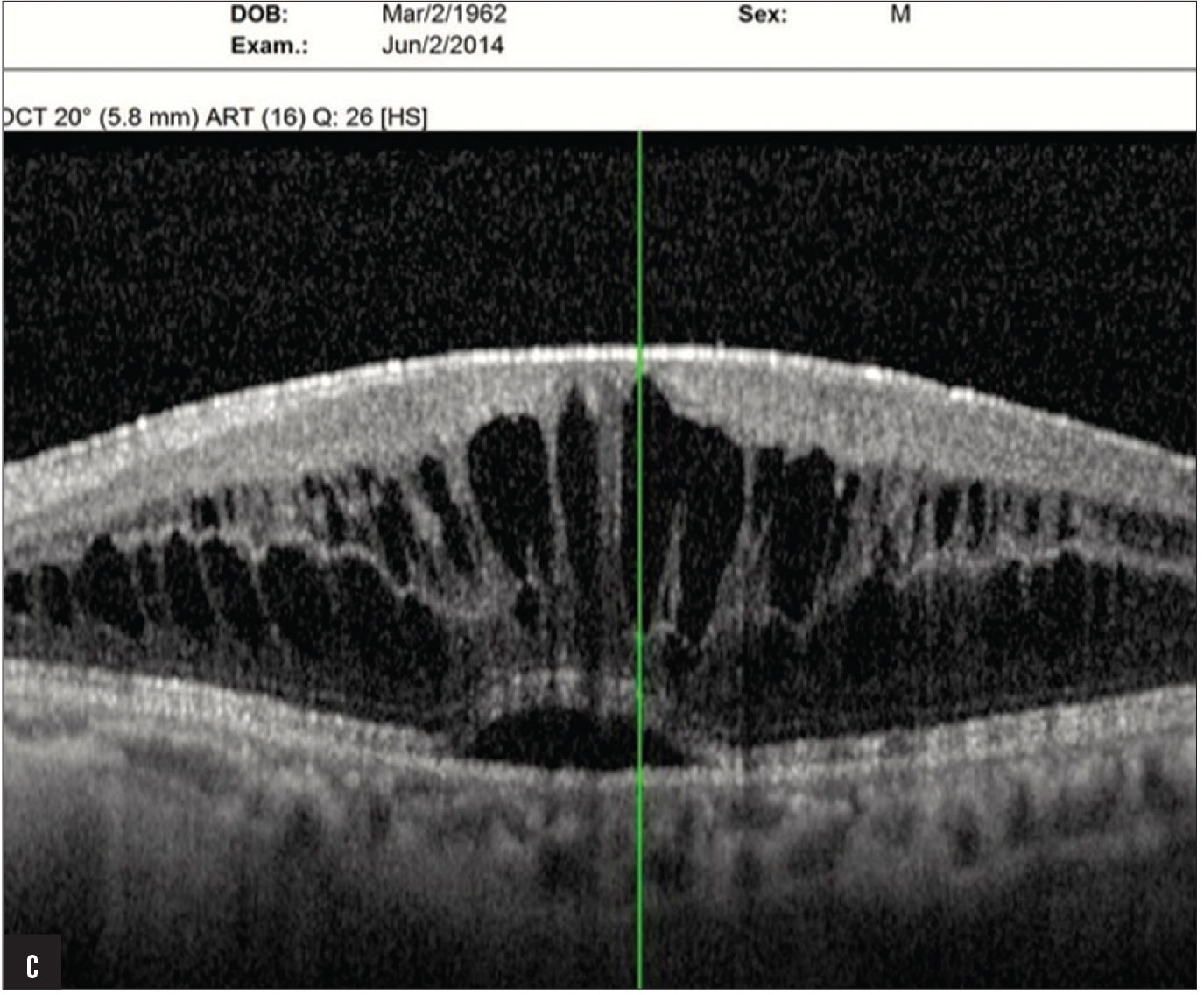

Figure 2. Intrascleral haptic fixation of a PC IOL using the Yamane technique. This technique requires familiarity with performing pars plana vitrectomy and creating scleral tunnels with a wide-bore, thin-walled, 30-gauge needle. Click image to enlarge. |

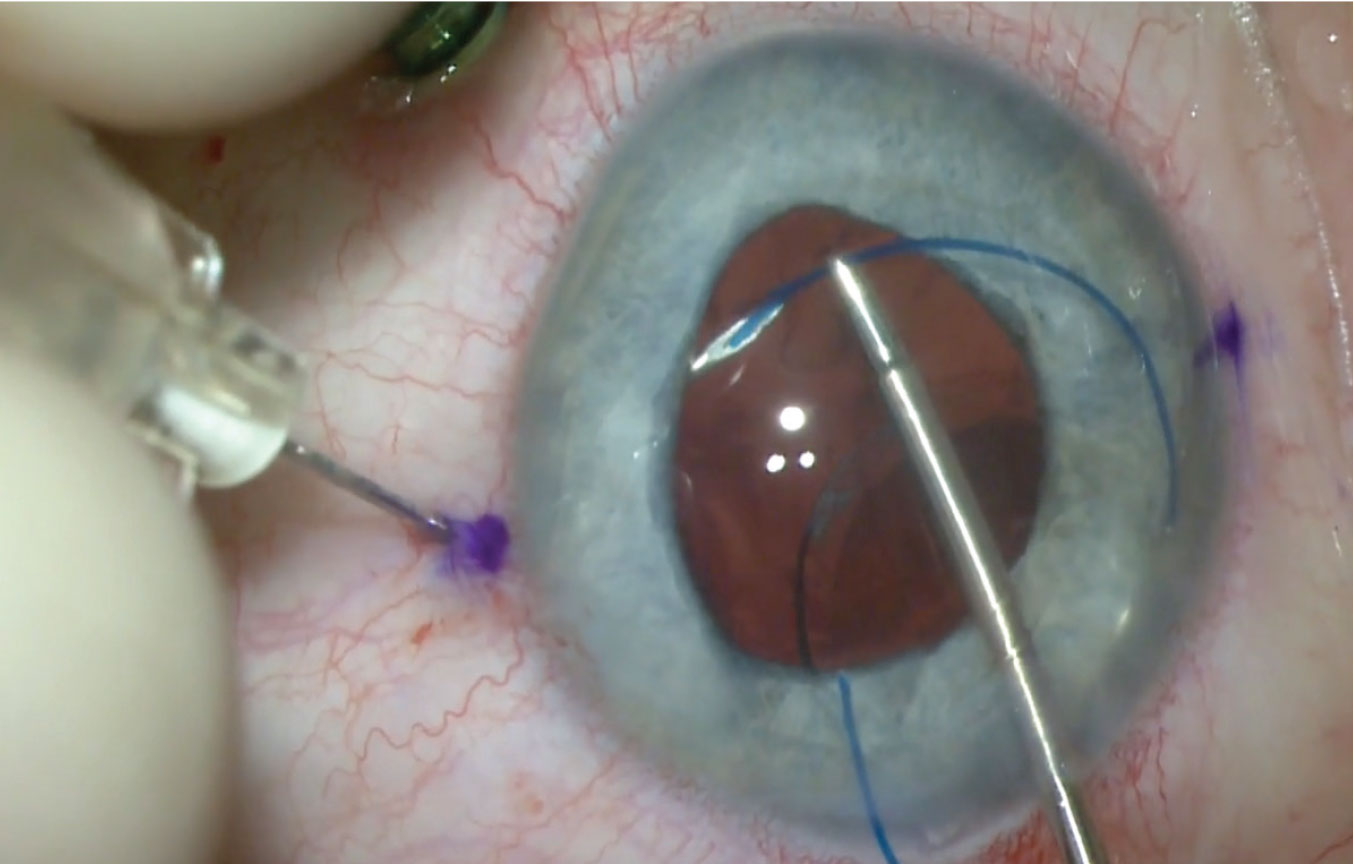

Amar Agarwal, MD, of Chennai, India, and his colleagues first described the glued IOL technique in 2007. This technique externalizes the haptics of a three-piece IOL thorough two sclerotomies spaced 180 degrees apart, which are then secured by tucking each haptic end into a tunnel. Glue is then applied to the haptics and the flaps are replaced over them.

In 2016, Shin Yamane, MD, of Yokohama, Japan, presented his flanged haptic technique, which requires neither glue nor sutures. The Yamane technique externalizes the haptics of a three-piece IOL through two sclerotomies and secures them by creating a flange with low-temperature cautery at the end of each haptic that prevents it from sliding back into the posterior chamber.

Besides avoiding complications related to sutures, an advantage of these techniques is that they’re intended for foldable implants. Dr. Hannush notes that this reduces the risk of iris prolapse, leakage, shallowing of the anterior chamber and suprachoroidal hemorrhage, mainly because of the small size of the incision compared to that required for suture fixation of a one-piece PMMA IOL.

Additionally, sutureless techniques take less time. “While sutureless scleral fixation requires a little more skill than suturing, it results in a quicker procedure with a shorter rehabilitation period,” Dr. Hannush says. He notes that the glued IOL technique takes a little longer to perform than the Yamane technique because there’s more dissection involved. “You have to take the conjunctiva down and create scleral flaps,” he says. “Any of the three-piece hydrophobic acrylic IOLs mentioned in the previous section may be used for ISHF, but the CT Lucia 602 from Zeiss is ideal mostly because of its PVDF haptics.”

|

|

Figure 3. The handshake maneuver is used for PC IOL haptic exteriorization while performing the glued IOL fixation technique. Click image to enlarge. |

Dr. Gorovoy points out that the Yamane technique doesn’t involve any dissection, so placement isn’t restricted by a requirement of “good real estate” that the glued IOL technique needs for flap creation. “The haptics can be near a bleb or a shunt,” he says.

“The Yamane technique is more difficult, however,” he continues. “For one, you’re threading needles through a soft eye, so you’ll need an anterior chamber maintainer or trocars. It’s also difficult to achieve centration, and you may get some tilt. Keeping your needles symmetrical is also a challenge because you’re passing blind needle tracks through the sclera. At the end of the day though, it doesn’t have to be perfect, just good.

“When done properly, it’s highly unlikely that the lens will dislocate again with the Yamane technique,” he says. “It’s by far the most secure method. This has a downside though: You won’t know how well-centered the lens is until you finish the procedure, and if you’re not happy with the centration or there’s tilt, it’s a big deal to redo. If the lens had been sutured and then decentered, you could just cut the suture and put in another.”

Learning these techniques is a challenge, but well worth the effort if you’re able to achieve proficiency, say surgeons. Here are some strategies for good outcomes:

• Be familiar with pars plana vitrectomy. “Familiarity with this technique is key for any scleral fixation method, especially sutureless,” Dr. Hannush says. “You need to remove the anterior vitreous body, and this is best achieved through the pars plana.”

• Be familiar with a sutureless ISHF technique. There are two options:

—The glued IOL technique requires familiarity with the handshake technique: “While the IOL is introduced into the anterior chamber with one hand, introduce a forceps through one sclerotomy site to grasp the leading haptic and externalize it,” Dr. Hannush says. “Through the other sclerotomy site, grasp and externalize the trailing haptic by transferring it from one hand to the other.”

—The Yamane technique requires familiarity with creating scleral tunnels with a wide-bore, thin-walled, 30-gauge needle that then receives the haptic of the IOL, externalizes it, then fixates it in the tunnel after creating a flange at the tip of the haptic with cautery.

• Mark the limbus precisely at 180 degrees. This is critical for achieving centration, especially if you’re using a multifocal lens. Dr. Gorovoy performs the Yamane technique with a limbal marker of his own design. “You need a marking system so your haptic needle placement is as symmetric as possible for optimal centration,” he says. “You don’t want to have to redo it.”

• Choose a lens with sturdy haptics. “The glued IOL technique is more forgiving, and you can use any three-piece lens,” says Dr. Hannush. “In the Yamane technique there’s more haptic manipulation, so you want to have a lens with sturdy haptics. The CT Lucia 602 (Zeiss) and the AR40 (J&J Vision) are good options.”

• Ensure the haptics are secure. “If the haptics aren’t secured properly into the scleral wall, the implant will either rotate or slip into the eye and migrate posteriorly,” Dr. Hannush says. He offers the following advice:

“For the glued IOL technique, deliver the IOL haptics into 26-gauge scleral tunnels for fixation. After placing an air bubble in the anterior chamber, inject reconstituted fibrin sealant to close the scleral flaps and conjunctival peritomies.

“For the Yamane technique, use hand-held cautery to flatten the haptic ends into a flange—a mushroom, pear-shaped or nail-head configuration. Push the haptic back through the conjunctiva into the sclera so the flange can barely be seen on the scleral surface.

Which Method Should You Choose?

While some methods have more serious complications than others, prospective studies haven’t proven the superiority of one method over another.4 Experts say the procedure you choose depends not only on what you’re most comfortable with, but also on the type of lens you’re working with.

|

|

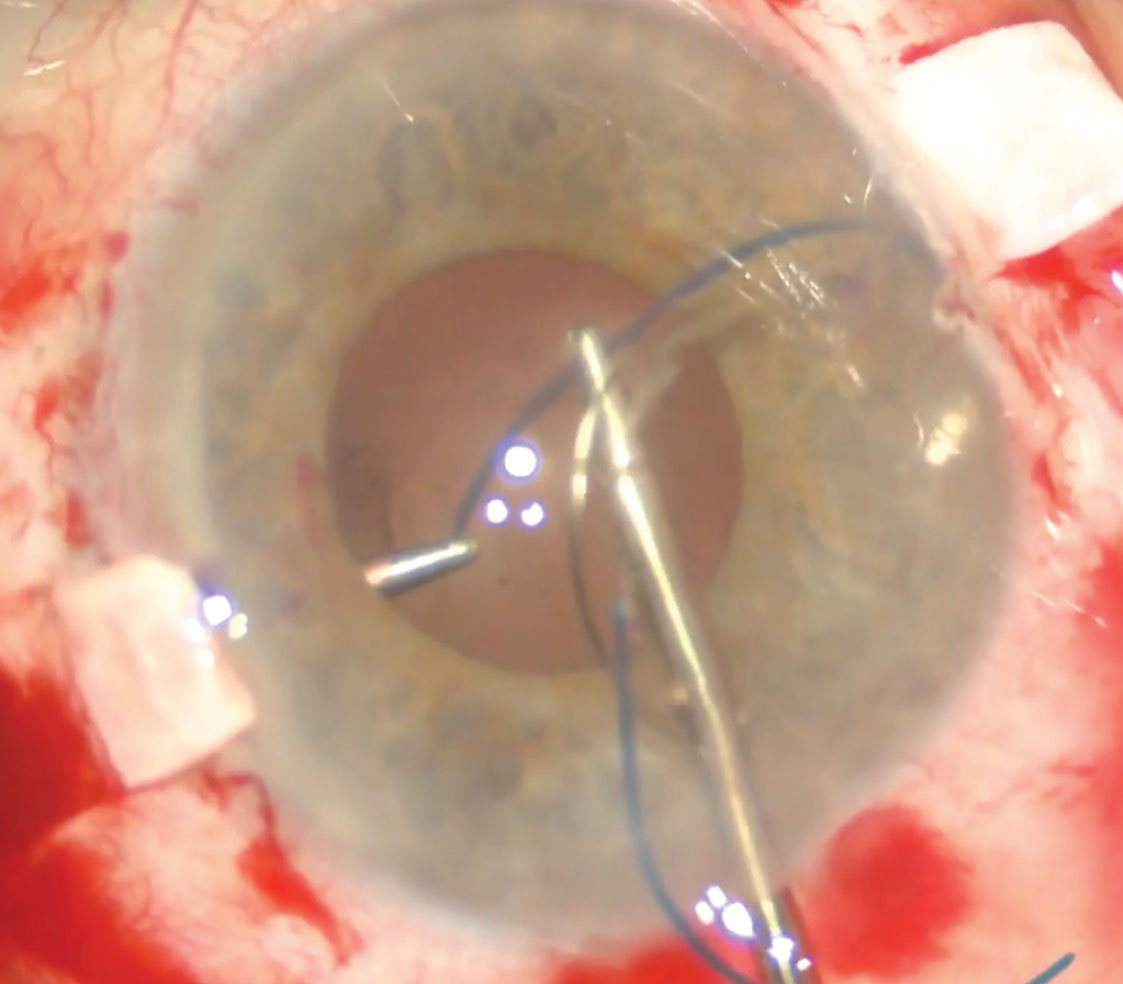

Figure 4. A subluxated one-piece acrylic PC IOL-capsular bag complex. One-piece acrylic lenses can be sutured if they’re still in the bag. The thick haptics on these lenses must be wrapped by the capsule to prevent chafing. Click image to enlarge. |

For Dr. Gorovoy and Dr. Hannush, a sutureless scleral fixation method is the optimal approach. “If the patient is aphakic or rendered aphakic and has a normal iris, my go-to technique is almost always a sutureless method,” Dr. Hannush says. “But if part of the iris is missing, I’d want a larger lens such as the CZ70BD, which has a 7-mm optic; this lens must be sutured. Alternatively, a sutureless foldable IOL may be combined with an artificial iris prosthesis.”

Dr. Gorovoy says his choice of scleral fixation depends heavily on the type of lens involved. The most common referrals he gets now are for pseudophakic eyes with loose or dislocated PC IOLs. “We’re seeing almost a mini-epidemic of late IOL dislocations now,” he says. “These are patients who had cataract surgery years ago with no problems. Then years later, the implant and capsular bag—usually the whole complex—dislocates. Twenty years ago, the major referral source would have been for removing AC IOLs and putting in new scleral-supported lenses, but because fewer AC IOLs are used now, we don’t see as many of those cases, thankfully. Now, it’s dislocations.”

He says the main reasons for this host of late dislocations are pseudoexfoliation syndrome and prior vitrectomy. “Many of these eyes had prior vitrectomies for retinal surgery,” he says. “It’s unclear why vitrectomy leads to later dislocation, but vitrectomized eyes behave differently. Bleeding can also be an issue for patients on anticoagulation medications.”

“When the lens is in the eye, dislocated, I’ll often use sutures because most of these lenses aren’t three-piece lenses,” Dr. Gorovoy says. “Unfortunately the trend in cataract surgery has been single-piece acrylic lenses. Those can be sutured if they’re still in the bag, but you can’t sclerally fixate them with a sutureless method.

“If I put in a new lens, I’ll almost always use the Yamane technique with three-piece lenses,” he adds. “Others favor single-piece PMMA lenses, but those require a much larger incision. The nice thing about the Yamane technique is that it’s done through an approximately 3-mm incision.”

Occasionally, patients with a subluxated lens are still happy with their vision. If that’s the case, surgery isn’t always warranted. Dr. Hannush cautions that it’s important to weigh the pros and cons of performing surgery on this group. “The first question you have to ask yourself as an examiner is, ‘Is the IOL position affecting the patient’s vision?’ I don’t usually intervene on patients with subluxated implants if they’re asymptomatic,” he says. “The risk of surgery outweighs the risk of doing nothing. If you intervene later when they’re symptomatic, the surgery is justified. Then, you can do a lens exchange and suture or intersclerally haptic-fixate the lens to the scleral wall. I don’t usually re-fixate the same lens; in most instances I prefer to exchange it, for many reasons, but many surgeons prefer to refixate the same IOL because of the perceived relative safety of this approach.”

Dr. Gorovoy is one of those surgeons. “Opening the eye with larger incisions or when using sutures puts the eye at greater risk for expulsive hemorrhage,” he cautions. “I believe it’s better to keep the eye closed than to open it up. By that principle, I try to take a dislocated IOL and keep it in the eye rather than take it out and exchange it for a new lens. Typically, I sew it to the sclera with 9-0 polypropylene and use a lassoing technique to lasso the haptic, sometimes pass it through the capsule, and secure it to the sclera.

“There are situations when you’ll have to extract the lens and put in a new one—sometimes because the current lens can’t be sutured or because it popped out of the bag and it’s a single-piece lens,” continues Dr. Gorovoy, who prefers to use the Yamane technique for a lens exchange. “We don’t want to suture single-piece lenses. Anything suture-fixated must be in the bag or be a three-piece lens or a single-piece PMMA lens, but it cannot be a single-piece acrylic lens. Acrylic lenses tend to have thick haptics, typically with square edges. If you suture them, they’ll chafe the iris and you’ll end up with UGH syndrome. For this reason we also don’t put those lenses in the sulcus. They have to be wrapped by the capsule.”

The Future of Fixation

With today’s advanced technologies and methods, surgeons say that large refractive errors are no longer acceptable. As noted earlier, however, achieving centration can be challenging with alternative fixation of IOLs, especially when using scleral fixation methods.

“When we do these scleral techniques, the calculations we use to figure out the lens power aren’t nearly as exact as they would be with routine cataract surgery,” Dr. Gorovoy says. “We don’t know exactly where the position of the lens will end up, and many of these eyes had prior surgery and may have significant preexisting astigmatism.”

He says the light adjustable lens (RxLAL, RxSight) has potential for these cases. “I have some reservations about silicone optics in aphakic eyes, which are complicated and may end up with future retinal detachments, but the idea of sclerally fixating a lens and being able to adjust the spherical corrections is really appealing. Ideally, we’d like to have a lens that can do that but with a haptic material that’s very flexible and forgiving to get in the needle tracks—something similar to that of the Zeiss lenses’ polyvinylidene fluoride monofilament haptics. I think an advance in this direction would make a big difference.”

Dr. Hannush and Dr. Gorovoy have no related financial disclosures.

1. Donaldson KE, Gorscak JJ, Budenz DL, et al. Anterior chamber and sutured posterior chamber intraocular lenses in eyes with poor capsular support. J Cataract Refract Surg 2005;31;5:903-909.

2. Hauff W. Calculating the diameter of the anterior chamber before implanting an artificial lens. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift 1987;171:1-19.

3. Yazdani-Abyaneh A, Djalilian AR, Fard MA. Iris fixation of posterior chamber intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg 2016;42:12:1707-12.

4. Shen JF, Deng S, Hammersmith KM, et al. Intraocular lens implantation in the absence of zonular support: An outcomes and safety update. A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmol 2020;127:9:1234-58.