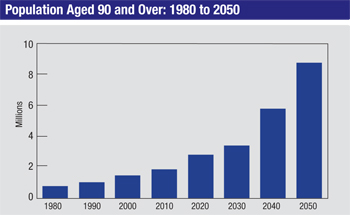

Today, however, Americans are living healthier lives with better medical care and preventive care, and this is increasing our life expectancy. The U.S. population over the age of 65 has doubled since 1980, and if current trends continue, the U.S. population over the age of 80 will triple by 2050. In fact, children born today are very likely to live to 100. Of course, this means an increasing number of glaucoma patients; age is a very important risk factor for the disease. As a result, many of us find ourselves managing patients for an extended period of time—and more patients who are over 80 or 90 years old.

The Super Senior

For our purposes here, let’s define a “super senior” as someone over the age of 90. The individuals in this age group are different from those of this age a few decades ago. Today these individuals may have some chronic medical conditions, but they often don’t have anything imminently life-threatening; they desire a continued high quality of life. These are people who are active, not sitting around in skilled nursing facilities. Many of them are still living independently.

These are not patients that you’d want to give up on or manage half-heartedly. You know that as their ability to ambulate decreases they’re going to depend more and more on their vision to lead a high-quality life. Good vision helps keep these individuals safe; among other things, they’ll have less risk of falling. And if someone has severe arthritis and can’t get around, his world gets smaller—but he really needs to see that world. So it’s important to not have someone in this group succumb to vision loss because of a progressive disease like glaucoma.

Given that we’re going to follow these patients for a much longer time than ophthalmologists would have in the past, we really have to think about how aging affects all of the aspects of managing glaucoma—from diagnosis to therapy to monitoring progression. We also have to be prepared to offer more help to the patient. Patients with arthritis may have more difficulty instilling drops; being on a fixed income can make costs a major issue; memory difficulties may lead to adherence problems; being on many systemic medications can lead to unexpected drug interactions and adverse effects; and so on.

The reality is, when you see somebody for the first time at the age of 70 and know that he or she could easily live another 20 to 30 years, you’re looking at a disease process that’s somewhat different from what you’d encounter in a younger patient. And today, you have to think about it in terms of the long run.

Monitoring the Patient

Visual field testing is an important part of monitoring progression in most glaucoma patients, but automated visual field testing may be much more difficult in elderly patients. Their reaction time is different and their attention span is shorter.

One helpful alternative is to try a kinetic (e.g., Goldmann) visual field test, which is much more user-friendly than automated static visual fields. In this type of testing, there’s a technician sitting with the patient who can alter the speed of the test and respond to the patient’s limitations. The Goldmann visual field test is not always reliable, but it’s often better than no formal testing at all.

Unfortunately, not all offices have the Goldmann technology today, and the instrumentation is no longer manufactured. Furthermore, fewer and fewer people are being trained to perform this test. That means this method of testing may soon be unavailable, but there are newer versions of automated kinetic visual field testing that are increasing in use. Hopefully, in the future there will be improved objective methods to obtain this functional data from patients.

Structural information about the optic nerve is very important and requires interpretation of optic nerve and retinal nerve fiber layer imaging scans; you’ll depend on them much more as an objective measure of progression with this group of patients. Of course, a key issue will be deciding whether a change is attributable to aging or progression. Unfortunately, most studies of optic nerve imaging have been cross-sectional; they look at different patients at a specific point in time. As a result, we don’t know a lot about longitudinal changes in OCT or HRT scans, or about what is normal for an aging individual.

|

Ultimately, you may not be able to get visual field information or measure retinal nerve fiber layer loss in some of these patients because of advanced optic nerve damage. In that situation you’re left with just the patient’s IOP and your gut instinct as to whether the patient is getting worse. If the mean pressure is 18 or 20 mmHg and the patient has advanced nerve damage and visual field loss and you feel the patient is getting worse, you’re probably right. But if the pressure is 12 or 10, it’s a lot harder to say whether the patient is getting worse; and its really hard to judge when the pressure is 14 or 16. Still, you have to make those difficult decisions and recommendations for therapy.

Treating the Super Senior

Given the limitations and special concerns that accompany treating an elderly patient, it’s important to approach this as a special case. A few points to keep in mind:

• Older treatment options may be worth considering. We do tend to treat elderly patients more with medications than with surgery, because we’re trying to avoid taking them to the operating room—especially if they have other co-morbidities. In addition, many of them are resistant to having surgery. For that reason it often makes sense to try alternatives you might not try with a younger patient. Some of the older medications, like pilocarpine and phospholine iodide, may be worth trying. Laser trabeculoplasty can also be a very good adjunct to medical therapy, and even transcleral diode cyclophotocoagulation may be beneficial in this population. I’ve had some very good results with diode CPC in elderly patients who didn’t want to have intraocular surgery in the OR.

• Make sure the patient and family understand that glaucoma eye drops are medications. The reality is that these drugs may have systemic effects, not just local effects on the eye. The patient and the family must be made aware of this.

Use of topical medications is sometimes overlooked by primary-care physicians, for example. I’ve had patients on beta blockers come back and say, “I had a pacemaker implanted a couple of months ago.” I look through their medication list and see that they’re on a topical beta blocker; beta blockers may cause bradycardia in some patients. I ask whether their cardiologist was aware of that. They say, “Oh yes, she made a list of all of my medicines.” But did the cardiologist consider that the topical beta blocker might be contributing to the patient’s need for a pacemaker?

• Be prepared to manage pressure-independent factors. In addition to IOP, blood flow-related factors such as ocular perfusion pressure and blood pressure are important; these may help us determine how much blood flow is reaching the optic nerve. Of course, when we’re managing these patients we lower intraocular pressure as much as we can, but if they’re still progressing and we don’t think we can easily lower the pressure further—i.e., surgery may be required—then it’s helpful to examine these other factors. (Sleep apnea is another important condition to consider for diagnosis and management.)

|

• If blood pressure is an issue, coordinate with the primary-care doctor. There’s sometimes a disparity in what we feel the blood pressure should be and what the primary-care doctor believes the blood pressure should be. Many primary-care doctors want the pressure as low as possible, as long as the patient is not falling. From our perspective, that’s not necessarily a good thing; we want to make sure the diastolic blood pressure stays over 60 mmHg so there will be less chance of hypotension, especially at night.

• Salt tablets at night may help keep blood pressure up. This is another strategy for helping to prevent hypotension. However, the best strategy is to coordinate your care with the primary-care doctor.

Seniors and Surgery

There are some special considerations when taking these patients to the OR, including issues surrounding informed consent (especially depending on the patient’s cognitive status); risks associated with anesthesia, which can have more profound effects in this age group; questions involving hygiene and infection risk; and avoiding suprachoroidal hemorrhages, which is a greater risk because of these patients’ vessel fragility, tissue quality and potential issues with their healing response.

Here are some strategies that will help make surgery go more smoothly:

• Make sure the informed consent involves the patient’s family. This is especially true if the patient’s cognition is impaired, and/or if the family is involved with managing the patient’s day-to-day living situation and there are legal guardianship issues.

• At the same time, make sure the ultimate decision is the patient’s. I’ve seen family members say, “Oh Grandma, you need to do this, the doctor says so.” As long as I feel that the patient can make the decision, I encourage the patient to make the decision. I give her the information she needs; I spell out the risks and benefits and how it relates to her quality of life currently and in the future. Then I let the patient know that it has to be her decision. I won’t schedule a procedure just because the patient’s family says the patient needs to do it.

If patients are not prepared to make that decision, I urge them go home and think about it, unless the procedure should be performed urgently. There’s often no reason to rush, so allowing them to think about the issues and giving them time to consider more questions is appropriate.

• Only broach the idea of avoiding “vision-saving” surgery if the eye is no longer helping the patient. Very few patients ever say they don’t care about their vision. The only time I hear that is when one eye is severely compromised in terms of visual acuity and visual field, and the other eye is perfectly normal. If a patient says, “You know doc, this eye is really not of any use to me,” I have the patient cover the better eye and try to cross the room. If the patient can’t make it to the door using only the worse eye—and I know the other eye is perfectly normal—then I’ll give them the option of skipping the surgery. However, if I think there’s any chance that the bad eye might become their better eye at some point in the course of their lifetime, then I’ll encourage them to proceed. Again, the final decision has to be theirs.

On the day of surgery:

• Avoid general anesthesia. I nearly always recommend monitored local anesthesia and sedation rather than general anesthesia, if at all possible. IV sedation with a short-acting drug such as propofol, which causes amnesia about what happens during the surgery, can be a good option. Even if the patient claims to feel something during the surgery, he probably won’t remember it. General anesthesia, where the patient is intubated on a breathing machine, is a much riskier procedure in this population.

Note that this is also a very important part of the informed consent with the patient and the family. Even if a patient says, “I don’t want to know anything about the surgery, I want to be put completely to sleep,” I really push against that. A trabeculectomy or tube shunt procedure is very safe for most of these patients when done using very short-acting sedative; there’s no reason to increase the risk by using general anesthesia.

• If possible, work with an anesthesiologist who has experience working with elderly patients in these types of procedures. Such an individual will know better when to give a little sedation and will know how to make the patient more aware when you want the patient to be more aware. That makes the surgery safer for everybody.

• Be cautious with the use of antimetabolites. My experience suggests that these patients have a thinner Tenon’s capsule, as it seems to become attenuated over time. They may have had prior surgery, leaving the conjunctiva scarred, more friable and easily torn, or the sclera more vulnerable, if the patient had a surgery such as an extracapsular cataract extraction, involving a large incision site at the limbus. Also, after decades of medication, their fibroblasts may be different. (We don’t know that for certain because there aren’t studies relating to that in this population, but we do know that long-term use of medication can alter the tissue.)

|

• Be aware that the patient may have had large-incision extracap cataract surgery many years ago. This should be factored into consideration when deciding where to make your incision. If a patient had extracapsular cataract extraction, the sutures may be gone, but that incision site will always be there;

your glaucoma surgery can get into trouble if you don’t realize that and make your incision at that location. You may not find this information in the patient’s record, either, if a 90-year-old patient had cataract surgery 30 years ago. So, make sure your physical exam considers this possibility.

If you determine that this is the case, you may want to alter which procedure you do. You might decide to put a tube in, rather than do a trabeculectomy or ExPress shunt, just because the tissue is not really amenable to a filtering procedure.

• Err on the side of higher postop pressures. Delayed suprachoroidal hemorrhage is probably our worst nightmare in glaucoma surgery; it’s associated with aging, hypertension, hardening of the arteries, arterial sclerosis and anticoagulant therapy. Recovery following a limited supra-choroidal hemorrhage is certainly possible, but this event is often devastating. Many super senior patients are on low-dose aspirin, and many others are on Plavix or Coumadin therapy because they’ve had some sort of cardiac procedure or have had a stroke in the past, putting them at greater risk. Patients with a suprachoroidal hemorrhage usually present to the office with acute, severe pain and loss of vision.

Delayed suprachoroidal hemorrhage can occur days or weeks after the surgery if the pressure in the eye drops low, so you need to be careful to avoid postop hypotony. I recommend putting in additional sutures at the end of surgery to keep the pressure a little bit higher for the first week or two after surgery. Avoiding lowering the head below the heart is also important.

• Make sure the family participates in post-surgery care. The family must be involved when it comes to follow-up appointments, and especially in terms of monitoring how the patient takes the medications after surgery. This can be a challenge for patients because the postop regimen may be very different from what they’ve been taking for their glaucoma. They may be accustomed to using drops once or twice a day, while the postoperative regimen could be every two to four hours. It’s definitely a step up in frequency of medication.

They may also need to change their activities for a while, although this is not usually a big change. These patients are not necessarily doing heavy lifting, but they may want to work in the garden; however, they’ll need to avoid doing this type of activity with a head-down position.

• Make sure the patient and family understand the signs and symptoms of infection. Infection does not appear to be a greater risk with elderly patients; at least there’s not much data supporting a greater risk. As long as the patient displays good hygiene and is compliant with therapy, this isn’t likely to become an issue. However, I’ve observed that sometimes when an infection does occur, the patient doesn’t come in right away because she “doesn’t want to bother anybody.” Thus, it’s very important to get the family involved, and say, “If you see any of these signs or symptoms, the patient needs to come in immediately.”

What About MIGS?

Microinvasive glaucoma surgeries, or MIGS, have garnered a lot of attention recently; they’ve raised the possibility of lowering pressure surgically without the risks and drawbacks associated with trabeculectomy and tube shunts. For a super senior, however, such an approach may not be all that useful, for two reasons. First of all, many MIGS procedures are approved by the Food and Drug Administration to be performed only at the time of cataract surgery. The majority of these patients had cataract surgery years earlier, so they wouldn’t be considered candidates for MIGS.

Second, while MIGS procedures are known for being safe, they don’t lower pressure nearly as dramatically as the more invasive surgeries. That’s a problem because if you don’t get the pressure reduction the patient needs to halt or decrease progression you’ll have to take the patient back into the OR for more surgery later. With a younger patient this may be very reasonable, but it doesn’t necessarily make sense when the patient is in her 90s. Surgery is inherently riskier at this age, and these patients may not be enthralled with the prospect of more surgery.

Yes, in some circumstances it might be a good option, as long as the patient understands and agrees. It might help to control the pressure for a few years and reduce the number of medications the patient has to use. Performing a MIGS procedure at the time of cataract extraction could be ideal for select patients in this population.

Keeping Things Super

Thanks to increasing life expectancy, all of us will be seeing patients for longer and longer stretches of time—and seeing more patients in their 80s and 90s (and maybe over 100). With any glaucoma patient, the ultimate goal of therapy is to improve the patient’s quality of life in terms of function and comfort. When the patient is a super senior, maintaining good vision is especially important: Being able to see well offsets some of the physical limitations that may

come with aging and gives the individual a fighting chance to continue activities such as driving that are so important to quality of life. (If we can also find ways to reduce the treatment burden, so much the better. Taking eye drops that make you miserable is not an ideal way to live.)

Today, my own parents are 86 and 96 and blessed with good health, an experience that I believe is increasingly common. Our attitudes about the elderly need to reflect that reality. You wouldn’t want to say to them, “Well, we’ll just kind of manage your glaucoma, and if you slowly lose vision, that’ll be OK.” With a little extra thought and persistence, we can help them maintain their best possible vision—and their quality of life. REVIEW

Dr. Siegfried is a professor in the department of ophthalmology and visual sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

1. Budenz DL1, Anderson DR, Varma R, et al. Determinants of normal retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measured by Stratus OCT. Ophthalmology 2007;114:6:1046-52.

2. Feuer WJ, Budenz DL, Anderson DR, Cantor L, Greenfield DS, Savell J, Schuman JS, Varma R. Topographic differences in the age-related changes in the retinal nerve fiber layer of normal eyes measured by Stratus optical coherence tomography. J Glaucoma 2011;20:3:133-8.