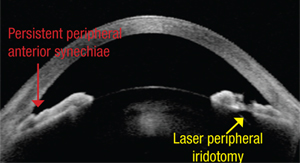

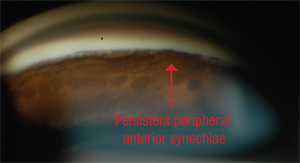

These patients may have narrow angles, intermittent angle closure, appositional closure, or closure with the development of peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS), termed chronic angle closure. If glaucomatous damage is present, then angle-closure glaucoma becomes the appropriate term. Angle closure can be caused by abnormalities in the relative or absolute sizes or positions of anterior segment structures, or by abnormal forces in the posterior segment that alter the anatomy of the anterior segment.

Our group has divided angle-closure mechanisms into four categories, depending on the site of the “force” causing iris apposition to the angle wall:1

• relative pupillary block (note that absolute pupillary block, where the iris is completely bound down to the lens by posterior synechiae, is rare);

• plateau iris, in which the ciliary body is large and/or anteriorly positioned and holds the iris against the trabecular meshwork (termed plateau iris syndrome when it is the cause of persistent appositional closure after the elimination of pupil-lary block by iridotomy);

• lens-induced or lens-related angle closure, in which the lens pushes the ciliary body and iris against the meshwork; and

• forces posterior to the lens.

|

If angle closure persists after iridotomy, argon laser peripheral iridoplasty is the next step, especially if a double-hump sign characteristic of plateau iris is present. ALPI may also be used as a primary procedure to break an attack of acute angle closure, almost always successfully, and to treat persistent angle closure in cases of lens-related and malignant glaucoma.2

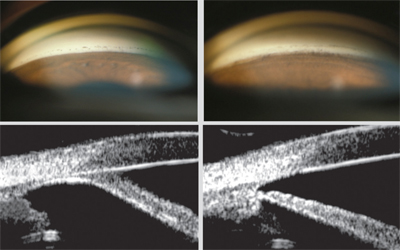

Early opening of the angle can restore aqueous outflow. If the angle is not opened, the chronic apposition will lead to increased pigmentation of the trabecular meshwork and eventually to the development of PAS—permanent adhesions between the iris and the meshwork. Performing laser iridotomy—and, if indicated by continued angle closure, ALPI—may not be the end of the story, however. If PAS are present (and these cannot be broken by ALPI, despite two reports in the literature claiming this) they may pose a threat even after the angle is opened. If PAS are extensive and uncontrolled glaucoma is present, surgical intervention becomes nec-essary.

Here, I’d like to share some of what we’ve learned about the sur-gical management of PAS, and the indications and use of goniosynechi-alysis to help patients who have de-veloped this problem.

Angle Closure and Outflow

Initially, PAS form on the inner surface of the meshwork, but pro-longed obstruction eventually leads to irreversible changes inside the meshwork, seen ultrastructurally, permanently blocking the outflow pathway at the site of the PAS. Unfortunately, cataract surgery alone does not eliminate PAS. Research has shown that up to 32 percent of patients with uncontrolled angle closure who underwent phacoemulsification alone still had persistent synechiae and uncontrolled pressure postoperatively.3

Goniosynechialysis was first described by David G. Campbell and Angela Vela in 1984. It is designed to strip PAS from the angle wall and restore trabecular function. The procedure consists of using a cyclodialysis spatula, an iris spatula, a bent 25-ga. needle or an Ahmed micrograsper to manually break the PAS. (I prefer to flatten PAS with a spatula under direct visualization to ensure that I don’t tear the iris with a forceps.)

When performing the procedure, the surgeon creates a paracentesis and allows the anterior chamber to shallow. In phakic eyes, massaging the eye will help to move aqueous from the posterior chamber to the anterior chamber. Once the anterior chamber has been filled with viscoelastic and the surgeon achieves clear, direct visualization of the angle, the synechiae are stripped one small segment at a time. The eye is rotated to reach as much of the angle as possible; if necessary, a second incision can be made. Following surgery, the patient should undergo a course of steroids (plus NSAIDs if the surgery was combined with cataract surgery), with pilocarpine used to help prevent reclosure of the angle.

|

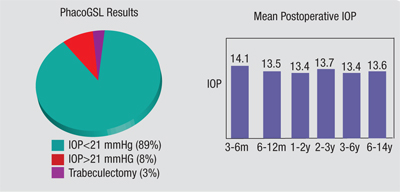

Back in 1999 I published a paper with Chaiwat Teekhasaenee, MD, in which we described the results of a large series of GSL procedures.4 We performed combined phacoemul-sification and GSL in 81 patients who had had primary angle closure for less than six months and had uncontrolled IOP following laser surgeries. They also had synechiae in more than 180 degrees of the angle. (See chart, above.)

Postoperative IOP was reduced to the low or mid-teens, regardless of the preoperative IOP. Eighty-nine percent of the subjects had a sig-nificant reduction of the synechiae, and their IOP was controlled without any medications; only 3 percent required subsequent trabeculectomy. The success rate did not change after the third postoperative month, and intraocular pressures were stable for up to 14 years, suggesting that long-lasting control is possible.

That series also demonstrated that if you do GSL, it is very important to remove the lens. Again, most of these eyes have angle closure, so they have a shallower anterior chamber and a steeper lens vault. Replacement of the natural lens with a thinner IOL creates space in the anterior chamber, discouraging PAS reformation. How-ever, the iris has “memory,” so if the lens remains and the angle is not grade 4, the iris creeps back up and undoes the GSL. We found this to be true even when we put patients on pilocarpine after the procedure. For that reason, our highest success rate was with the patients in whom we removed the lens, did the GSL simultaneously and then kept the patients on pilocarpine for a while afterwards to keep the angle open and prevent the iris from creeping back up.

Other studies have confirmed the efficacy of this combination procedure.5-7

Surgical Considerations

When deciding whether GSL is necessary, there are a number of factors to consider. Good candidates for this procedure include eyes with a previously normal trabecular meshwork that now have chronic angle closure—eyes that have undergone iridotomy and possibly iridoplasty, with 50 percent or more of the angle sealed by PAS and an elevated IOP. Recent synechial closure is usually associated with better results.

|

Other factors to consider:

• You don’t always need to perform GSL. If the patient has 20/25 vision and you do an iridotomy and only half the angle opens up, you probably wouldn’t want to perform GSL as long as the pressure is 16 mmHg. Why do surgery if the pressure is normal? Maybe it will stay normal until the patient is 90 years old. Similarly, if you put the patient on a couple of drops, the pressure is well-controlled and any PAS seem to be unchanging, I’d observe the patient, rather than performing GSL.

• When possible, combine GSL with cataract surgery. If the patient was having a cataract removed, even if the IOP was controlled on several medications, I would combine GSL with the cataract surgery. And, I would not postpone cataract surgery if a patient receiving GSL was a can-didate for cataract removal. Our research found that the results of per-forming GSL were significantly better when the lens was removed.

• A limited GSL may be better than none at all. There are conditions under which it may be ac-ceptable (or necessary) to perform a limited GSL procedure. (If the patient only has 180 degrees of PAS, you only need to address that part of the angle.) In some situations, it may be difficult or impossible to treat 360 degrees. Maybe you can’t make a second incision; maybe you can’t get your microscope positioned appropriately; maybe you can’t see the entire angle. When this occurs, it’s worth doing as much of the angle as you can; even half might be sufficient to get the pressure down and preserve the patient’s vision.

For example, one published study involved a series of five patients with chronic angle-closure glaucoma and total synechial angle closure whose intraocular pressures were >21 mmHg on maximally tolerated medications. They received 180 degrees of inferior GSL followed by argon laser peripheral iridotomy.8 Mean IOP dropped from 33.8 mmHg preoperatively to 15.8 mmHg postoperatively. The success rate was 80 percent.

• It may be worth following up with other surgeries, if necessary. If the PAS have been present for more than a year and GSL is expected to have limited effect, it’s possible to try other follow-up options. I’ve tried performing goniotomy, just as I might for congenital glaucoma. This creates a slit in the trabecular meshwork, allowing aqueous access to the outer meshwork, even if the inner meshwork is blocked by ingrown iris tissue. In theory, another possibility would be using the Trabectome, although this approach has not been described in the literature.

|

The only way to prove that SLT actually reduces the impact of the synechiae themselves would be to try it in a series of cases in which the trabecular meshwork was totally sealed by PAS when the GSL was performed. (Fortunately, I don’t see many patients with angles totally sealed by PAS—unlike 30 years ago, when angle closure was chronically misdiagnosed. Ninety percent of the patients who came to see me with angle closure back then came in misdiagnosed with POAG.)

Following GSL with argon laser trabeculoplasty would be another possibility.

• Complications are relatively rare. Of course, complications are always possible in this type of surgery; you can tear the iris and cause iridodialysis, hyphema or bleeding, and you have to be on the lookout for inflammation and IOP spikes. The most common complication is hyphema, because you’re tearing into tissue. Careful treatment of the delicate iris tissue and a good gonioscopic view are important.

A Valuable Procedure

It’s difficult to know how often GSL is not done when it would benefit the patient, but my guess is that it is probably underperformed. (The procedure is more popular in Asia than in the United States or Europe.) If it is underutilized, it’s unlikely to be the result of overlooking the presence of PAS; the only reason a clinician would overlook the presence of PAS is lack of experience with gonioscopy. (Although there is no substitute for gonioscopy, perhaps the availability of anterior segment optical coherence tomography will improve the ability of clinicians to diagnose synechial angle closure.)

A more likely reason that GSL might be underutilized would be a reflexive reliance on other procedures to lower pressure, such as trabeculectomy. If GSL can relieve elevated IOP, it is a far safer way to reduce IOP than more extensive surgery; it utilizes the natural outflow pathway, and it doesn’t have the kind of long-term risks seen with filtration procedures. It’s certainly an option to consider when managing a patient with angle-closure issues. REVIEW

Dr. Ritch is surgeon director and chief of glaucoma services at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary, New York City, professor of clinical ophthalmology at The New York Medical College in Valhalla, N.Y., and medical director of The Glaucoma Foundation.

1. Ritch R, Liebmann J, Tello C. A construct for understanding angle-closure glaucoma: The role of ultrasound biomicroscopy. In: Ophthalmol Clin N Amer, WB Saunders Co, Philadelphia 1995;8:281-293.

2. Ritch R, Tham CCY, Lam DSC. Argon laser peripheral iridoplasty—update 2007. Surv Ophthalmol 2007;52:279-288.

3. Aung T, Tow SL, et al. Trabeculectomy for acute primary angle closure. Ophthalmology 2000:107:1298-1302

4. Teekhasaenee C, Ritch R. Combined PhacoGSL for uncontrolled chronic angle-closure glaucoma after acute angle-closure glaucoma. Ophthalmology 1999;106:669-75.

5. Lai JSM, Tham CCY, Lam DS. The efficacy and safety of combined phacoemulsification, intraocular lens implantation, and limited goniosynechialysis, followed by diode laser peripheral iridoplasty, in the treatment of cataract and chronic angle-closure glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2001;10:309-15.

6. Kanamori A, et al. Goniosynechialysis with lens aspiration and posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation for glaucoma in spherophakia. J Cataract Refract Surg 2004; 30:513-6.

7. Harasymowycz PJ. et al. Phacoemulsification and goniosynechialysis in the management of unresponsive primary angle closure. J Glaucoma 2005; 14:186-9.

8. Lai JSM, Tham CCY, Chua JKH, Lam DSC. Efficacy and safety of inferior 180° goniosynechialysis followed by diode laser peripheral iridoplasty in the treatment of chronic angle-closure glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2000;9:388-391.