|

|

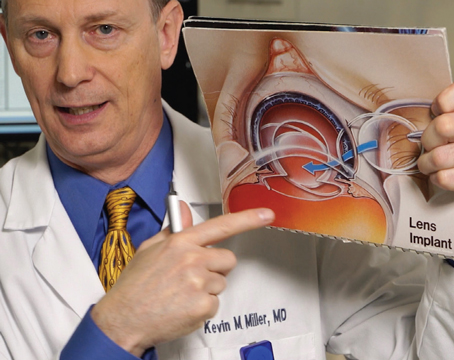

Following LASIK surgery, there’s a small population of patients who experience chronic pain that doesn’t respond to traditional dry-eye treatments. Experts say they require more aggressive, systemic treatment to help heal the nerves. |

For a majority of LASIK patients, recovery will go as expected, healing fully within three to six months. However, refractive surgeons may encounter the rare patient who continues to suffer from dry-eye symptoms with no relief, some of which can be severe and disruptive to their daily life and mental health. We spoke with cornea and refractive surgery specialists who offered guidance on treating these cases.

Post-LASIK Chronic Dry Eye

Historically, one of the most appealing aspects of LASIK has been its quick recovery time. Patients will see more clearly within 24 hours and they can usually return to their normal activities within just a couple of days of surgery, yet the eyes themselves can take several months to fully heal, and for a small population of patients, even longer.

Dry-eye symptoms are the most common complaints in the early postop period, occurring in as much as 60 percent of patients one month following LASIK.1 Although there’s no surefire way to predict the severity of dry eye that individual patients may experience, studies have shown that factors such as sex, ethnicity, contact lens use, eyelid anomalies and diabetes have been associated with increased risk of dryness.1

Extensive research and education has been undertaken by the field of ophthalmology to treat the ocular surface prior to surgery, and more often than not, it’s the group of patients who don’t tolerate contact lens wear that seeks out refractive surgery and may need more aggressive treatment, explains David R. Hardten, MD, of Minnesota Eye Consultants.

“Much of why they don’t tolerate contact lenses very well is due to ocular rosacea, blepharitis or dry eye,” he says. “We can see that they have a little bit of intermittent punctate staining when they’ve been seen in the past and that’s why they’ve had to stop their contact lenses. We tend to be more aggressive in controlling these underlying conditions for those patients because now they no longer have the air-blocking effects of a contact on their eyes, or glasses in front of their eyes. It takes a while for them to become re-accustomed to having their eyes open to the air. In addition, they’ve often developed a poor blink reflex with contacts; blinking partially, feeling their contact lens with half blink; so they have to learn to blink again.”

Dr. Hardten proceeds with treatment to optimize the ocular surface. “They stop wearing contact lenses, then we treat with cyclosporine drops or lifitegrast (Xiidra), sometimes doxycycline orally, and Omega-7 to help with gland dysfunction. In some patients where we see intermittent punctate keratitis preoperatively we might even do in-office treatments like Intense Pulsed Light, LipiFlow or TearCare in advance to get their ocular surface ready,” he says.

|

|

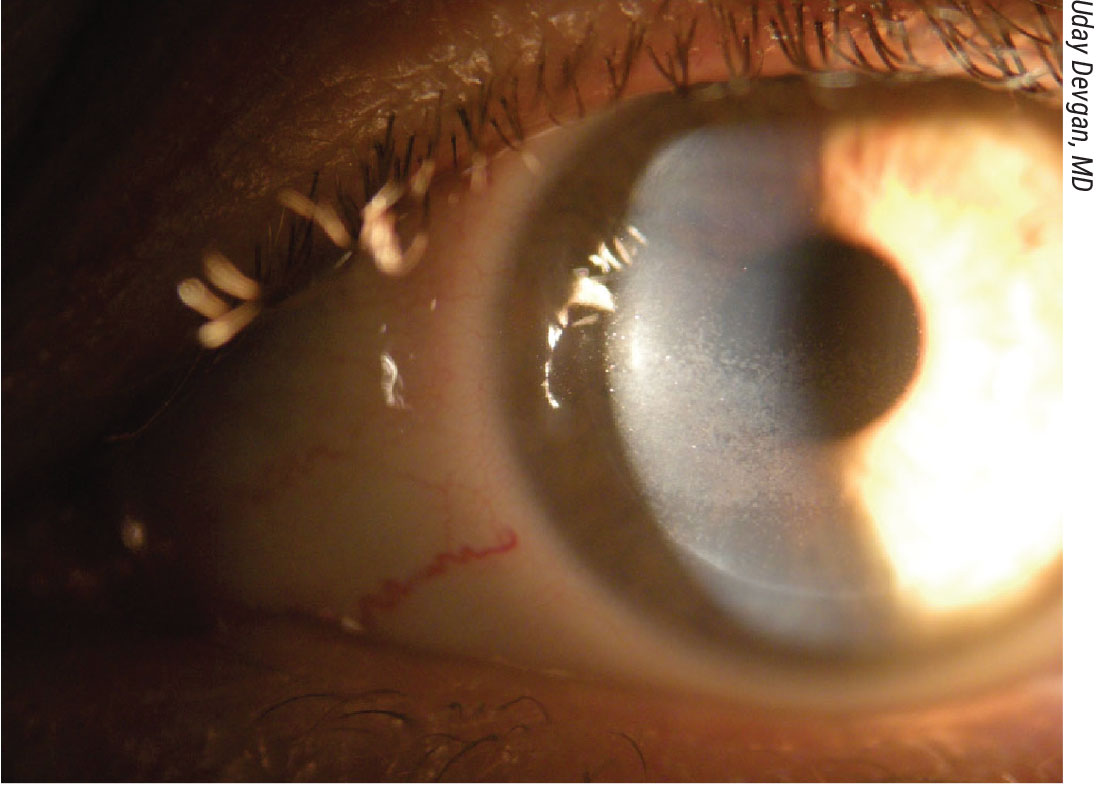

Approximately 60 percent of patients who undergo LASIK surgery will experience postop dry eye. Preop screening and treatment for ocular surface disease has become an important component of refractive surgery to improve these outcomes. |

Following surgery, dry eye improves within three months, or six months in some outliers, says Deborah S. Jacobs, MD, MS, director of the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Ocular Surface Imaging Center. “It’s really hard to distinguish these patients from the broad variety of patients who might see well, but have various types of discomfort in the immediate postop period. Most are treated as ‘dry eye’ with lubricating drops and punctal occlusion. Some may be given drops that improve tear secretion like cyclosporine or lifitegrast, or a more prolonged course of topical steroid or with autologous serum tears,” she says.

While working as a clinician at a referral center, Dr. Jacobs was introduced to patients still suffering with ocular surface disease and were years past their LASIK procedure. Many were referred for a therapeutic scleral lens. “What we’ve learned about this condition in hindsight is patients typically may have severe pain from the day after LASIK on, but more typically they have symptoms that might be interpreted as dry eye: gritty feeling; dry feeling; and a sensitivity to light and moving air,” she says. “However, some of these patients seem to not get better, or they even get worse. And that’s when they start to stand out from the run-of-the-mill dry eye that occurs after LASIK.”

Neuropathic Corneal Pain

More severe and more rare are persistent and debilitating symptoms that have been classified as neuropathic corneal pain, a subtype of dry-eye syndrome. Many of these patients didn’t present with dry-eye symptoms prior to LASIK, adding to the mystery around the contributing factors to this condition.

Dr. Jacobs says the LASIK procedure itself can trigger this pain syndrome in some people.

“The flap is a different kind of trauma and generally eyes did well after LASIK, but when you make the flap, you cut nerves that innervate the front of the eye,” she says. “Those nerves are important for sensation, and just as important for detecting evaporation or change in temperature; those nerves are part of the homeostasis of the ocular surface. They’re part of the pathway that causes us to tear and secrete mucin, and cutting the nerves themselves doesn’t cause pain, but eyes that have had their nerves cut may have altered sensations; they may feel dry during the healing process, the eyes may actually be dry, and we think that, in a small fraction of patients, cutting these nerves is what triggers pain syndrome.”

In most patients this is transient and below their detection, says Dr. Hardten. “Initially we would treat it with the usual therapies we use for controlling postop inflammation, dry eye or blepharitis. But, if there’s persistent discomfort in the setting of a normal exam, then we begin to think of this as neuropathic pain.”

It’s hard to know if the problem is neuropathic until treatment plays out, says Dr. Jacobs. For instance, patients may complain of rainbow glare or have light sensitivity. “Those patients may fall into this category of postop discomfort or pain,” she says. “The complaints are visual, but clinicians tend to lump these all together and give them lubricating drops and tell them they’ll get better and most of them do. However, we know that the transient light sensitivity syndrome, which appears in the second to fourth week after LASIK, may require systemic steroids. Rainbow glare is an optical phenomenon, and some of those patients benefit from lasering the flap, but when someone comes back to the office for their one day or one week check and they’re uncomfortable or unhappy, it’s hard to know if they’re the expected dry eye or one of the other issues until it starts to play itself out.”

Dr. Hardten says his usual course of therapies would include resuming topical steroids. “Medications used systemically for atypical pain are useful, such as pregabalin (Lyrica) or gabapentin (Neurontin),” he says. “Additional therapies such as Omega-7, scleral lenses, lacosamide, non-steroidal agents, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, amniotic membrane and autologous tears have also been reported to be effective in some patients. Acupuncture or botulinum toxin have also been reported effective in some patients.”

If a patient doesn’t respond to traditional therapies, Dr. Jacobs says ophthalmologists must understand and consider some of the principles of persistent postoperative pain or complex regional pain syndrome.

“This syndrome has a name when it affects other parts of the body, yet ophthalmologists just aren’t aware of it,” she says. “But once they fall in that category, the patient needs aggressive treatment of pain and that’s often multimodal, consisting of local treatment and systemic treatment, and sometimes behavioral and cognitive approaches as well, to help them escape from this rather than end up years down the line in a chronic pain state.”

As eyes are healing, Dr. Jacobs says it’s important to reduce the signaling. “I like to say that those eyes are on high alert and they tend to send false alarms at the slightest little trigger: bright light; dryness; evaporation. We have to make the eyes less triggerable,” she says. “I like to use topical steroids. I often choose a soft steroid like loteprednol or fluorometholone. A little is good; a lot is not better. If patients don’t respond to a little soft steroid I don’t necessarily go for more or stronger steroid, but I add a different drug or topical agent and/or a different approach. I’ll offer a bandage soft lens or a scleral lens to dampen the signaling, but if the nerves are still hyper alert and they’re super sensitive, then that’s where systemic therapy comes in.”

Due to its safety profile and efficacy for peripheral nerve pain, gabapentin is a common initial therapy. “I typically start with 300 mg at bedtime and go up over a couple of days to 300 mg three times a day or four times a day,” Dr. Jacobs says. “I would increase the nighttime dose to 600 mg. The main side effect is sedation, but you want to help the patient get relief so they can go about their business and not be bothered. In more chronic cases or if the gabapentin doesn’t work, I might consider a bedtime dose of nortriptyline, or switch to pregabalin or duloxetine.”

There may also be value in the use of serum tears or platelet rich plasma drops, although Dr. Jacobs says she would use them in the earlier phase of healing. “As far as getting the eye to heal properly or getting the nerves to heal properly, I like to focus on reducing inflammation initially, but there’s value to serum tears or PRP drops certainly, at least as a lubricant, and because they contain molecules that can modulate inflammation and promote nerve healing,” she says. “Serum tears have been shown to promote epithelial healing, so serum tears or PRP or other blood products aren’t a bad idea in someone who is unexpectedly symptomatic in the early postop period. In the chronic period after a year out, I’m not sure what the value is, so I’d probably only use serum tears in the earliest healing period. That’s probably where the greatest potential for biologics lies.”

Many of these patients have tried and abandoned treatments suggested by one doctor or another, Dr. Jacobs continues, and are often seeking a magic bullet. “They want something that works completely right away. My experience is that it often takes multimodal treatment with systemic and topical agents, shielding against evaporation and time. If someone’s had pain for months, it’s not going to go away in days or weeks,” she says. “And that’s one of the challenges with people who are suffering, understandably. There’s no expected timeframe except that if pain has been chronic, likely emergence is going to be in the same order of magnitude, from months to years, same as if the pain has been months to years.”

Despite the rarity of neuropathic corneal pain, studies have investigated comorbidities that may increase a person’s risk, such as chronic widespread pain, irritable bowel syndrome and pelvic pain,2 as well as fibromyalgia, autoimmune diseases and thyroid diseases.3

“We now know that patients who have other pain syndromes, such as low back pain, complex regional pain (after a knee surgery for instance), fibromyalgia and migraines—those patients are more likely we think to develop persistent postop pain syndrome like post LASIK neuralgia,” says Dr. Jacobs. “I think as part of refractive surgery screening, it’s important to consider if any of these are in the background and if patients are taking drugs for anxiety or depression. Depression is a risk factor for persistent postoperative pain. It’s likely that before we understood this as well as we do now, there were patients who were operated on who nowadays, we might screen out.”

In collaboration with Stephen Waxman, MD, PhD—a molecular neuroscientist at Yale—Dr. Jacobs is looking into the possibility of any shared gene mutations or variants in people who have persistent pain after refractive surgery. “If we found a common mutation, we could test and screen out these patients, but so far there doesn’t seem to be one gene, so we can’t say if it’s a nerve, collagen or inflammation gene,” Dr. Jacobs says. “It’s still a work in progress. However, if a candidate has a first-degree relative who has post-LASIK pain syndrome, I would hesitate to recommend LASIK for that candidate.”

Dr. Hardten concludes, saying, “Neuropathic pain is atypical, although we see it after refractive surgery, cataract surgery; I’ve even seen it after a patient got sunscreen in their eyes. It can happen with any kind of insult to the eye. There’s probably less than 30 patients a year in the U.S. who really develop persistent ongoing issues that don’t resolve after six to nine months, but it’s still something that’s important to consider.”

Dr. Hardten reports no disclosures. Dr. Jacobs is a consultant for Dompe Therapeutics.

1. Yu EY, Leung A, Rao S, Lam DS. Effect of laser in situ keratomileusis on tear stability. Ophthalmology 2000;107:12:2131-5.

2. Galor A, Covington D, Levitt AE, McManus KT, Seiden B, Felix ER, Kalangara J, Feuer W, Patin DJ, Martin ER, Sarantopoulos KD, Levitt RC. Neuropathic ocular pain due to dry eye is associated with multiple comorbid chronic pain syndromes. J Pain 2016;17:3:310-8.

3. Moshirfar M, Bhavsar UM, Durnford KM, McCabe SE, Ronquillo YC, Lewis AL, Hoopes PC. Neuropathic corneal pain following LASIK surgery: A retrospective case series. Ophthalmol Ther 2021;10:3:677-689.