Corneal ulcers are a leading cause of blindness worldwide with at least 1.5 to 2 million cases estimated annually. Because progression can lead to significant corneal melt, perforation, endophthalmitis and corneal blindness, diagnosis and management are time sensitive.

Epidemiology

Infectious keratitis is particularly prevalent in developing countries that have difficult access to medical care, risk for trauma related to agricultural work, and worse health at baseline.

In more developed countries, the incidence of microbial keratitis is increasing, due to the prevalence of contact lens use and instances of poor contact lens hygiene.

The specific pathogens of infectious keratitis have geographic differences based on climate-related flora and type of trauma, including contact lens wear. In Europe, North America and Australia, for example, microbial keratitis is typically Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus or Pseudomonas aeruginosa.1 In contrast, the Asia Corneal Society Infectious Keratitis Study reports a predominance of fungal keratitis, Fusarium, in India and China. The worldwide prevalence of Acanthamoeba is about 1 to 3 percent of infectious keratitis.2

|

| In cases of Acanthamoeba infection, the patient’s photophobia and pain are out of proportion with what is seen on the clinical exam. |

Diagnosis

The definitive diagnosis of infectious keratitis can be achieved via the following:

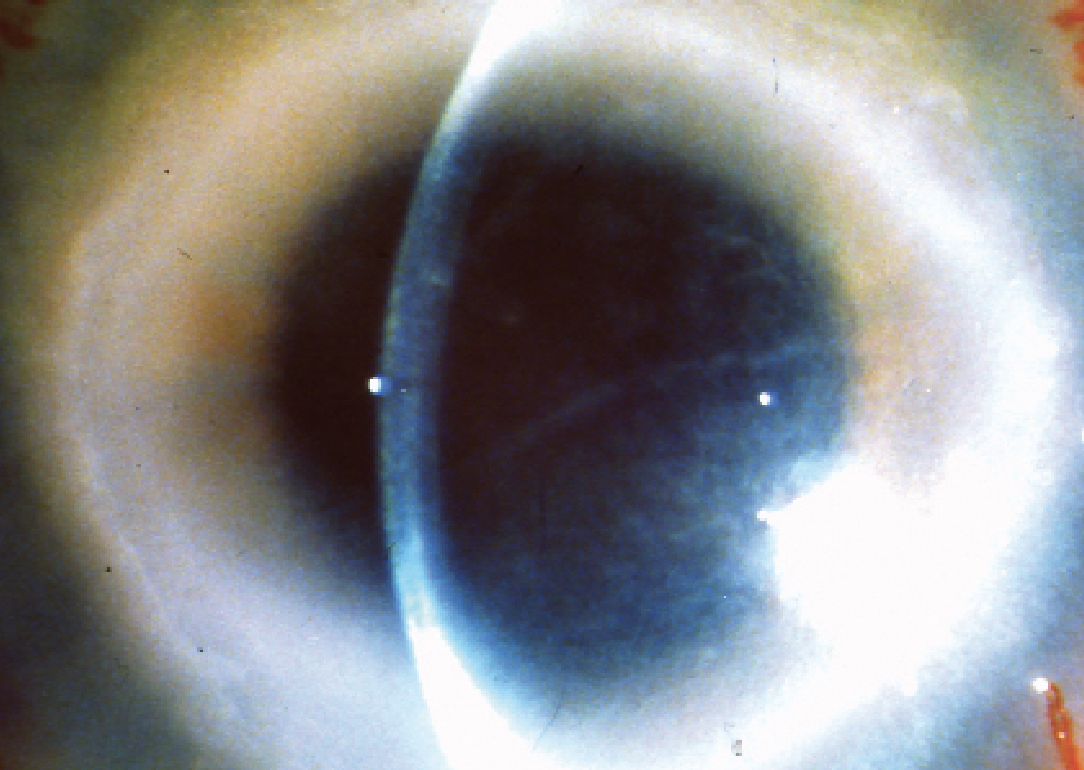

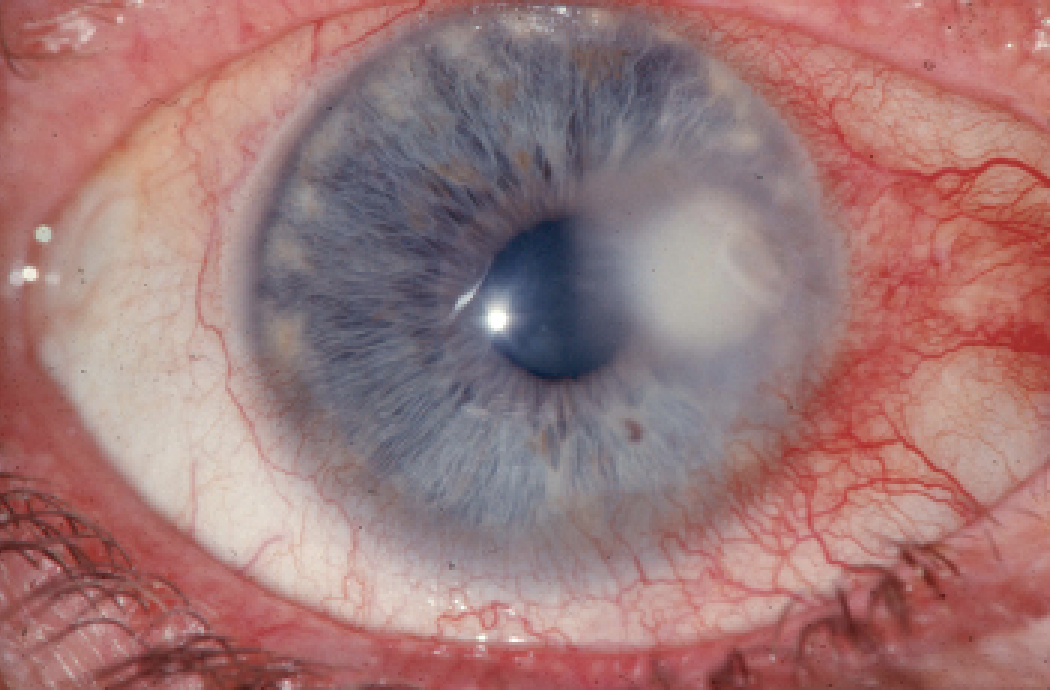

• Clinical presentation. Bacterial keratitis typically presents as an epithelial defect with a suppurative stromal infiltrate that can progress to varying degrees of thinning. Surrounding structures exhibit inflammation, such as lid swelling, ciliary flush, corneal edema and iritis with or without a sterile hypopyon.

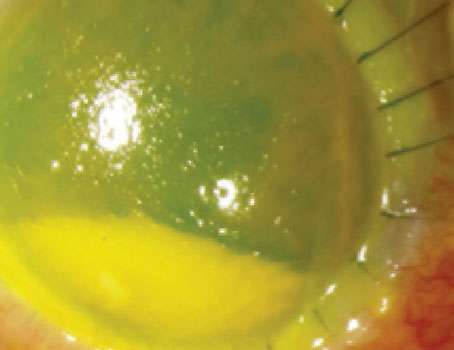

Certain causes of infectious keratitis are more clinically indistinguishable from each other, making diagnosis difficult. Acanthamoeba and herpes simplex virus both start with irregular epithelia and photophobia. For Acanthamoeba, the photophobia and pain are out of proportion with what is seen on the clinical exam, meaning the patient’s pain is worse than what’s seen clinically. In more advanced stages, a pathognomonic ring-shaped infiltrate or perineuritis can develop.

The risk factors for Acanthamoeba keratitis are contact lens use, freshwater exposure (e.g., swimming pools and hot tubs) and agricultural trauma. For HSV, a history of hypoesthesia, cold sores, recurrent unilateral eye infections and a history of dendritic or geographic epithelial defects are characteristic of herpetic keratitis.

• Microbiology workup. A consensus published by the AAO Preferred Practice Pattern recommends staining and culture for ulcers that are larger than 2 mm, vision-threatening by depth of involvement, show stromal melt, have a central location, are refractory, or those that appear in eyes that have undergone ocular surgery.3 Specimens for stains and cultures are obtained at the leading edge of infiltrates. Ways to maximize yield include collecting specimens with a broth-moistened calcium alginate swab, Dacron swab or a sterile metallic instrument. Avoid tetracaine and BAK use in order to preserve the viability of the pathogen. Careful sample collection prevents contact with lashes and the conjunctiva where the normal flora can confound the results.3

Microbial culture is considered the gold standard, because identifying the organism often confirms the diagnosis.3 A major challenge with cultures is their limited yield. The sensitivity of using blood, chocolate, thioglycolate and mannitol bacterial media is approximately 42 to 58 percent. Sensitivity is even more limited for Acanthamoeba at about 33 to 60 percent, in either buffered charcoal yeast extract or E. coli overlay on non-nutrient agar.

The low sensitivity of cultures and prolonged incubation periods warrant adjunctive methods to quickly identify pathogens with staining methods. Gram stains can be used to visualize bacteria, fungi and Acanthamoeba. The sensitivity for identifying bacteria ranges from 36 to 75 percent. KOH wet mounts are 68 to 98 percent sensitive for fungal species, whereas it’s higher at 84 to 91 percent for Acanthamoeba.4

Polymerase chain reactions and PCR-based assays have a sensitivity of 73 to 90 percent, with a specificity of 94.7 to 98 percent for both bacteria and fungi. PCR can also identify Acanthamoeba.

Confocal microscopy can aid in identifying atypical organisms and in assessing the depth of corneal involvement. Using this technology, Acanthamoeba appears as a hyperreflective, spherical and well-defined double-walled cyst.5 Bacteria are too small and obscured by a sea of inflammatory cells to be detectable. One exception is Nocardia.

Several challenges exist with confocal microscopy, however: it’s mainly a research tool, limiting access; it’s poorly reimbursed by insurance, therefore patients may have to pay for the test; the false-negative and false-positive rates are high; and the person administering the test should have significant experience, since identifying normal—let alone pathology—is difficult for the novice.

|

| The American Academy of Ophthalmology criteria for staining and culturing for ulcers includes such factors as a size larger than 2 mm, a central location and stromal melt. |

Treatment

Treatment is targeted to the etiology to reduce ocular morbidity and visual impairment. Empiric therapy for bacterial ulcers involves frequent dosing of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Loading doses can be applied initially, followed by hourly dosing while awake, until clinical improvement. Then, the dose can decrease to q2hrs until re-epithelialization of the cornea, followed by further reduction to q.i.d until resolution.3

Treatment for Acanthamoeba keratitis requires clearance of both cystic and trophozoite forms of the parasite. Early amoebic keratitis is mainly intraepithelial, and debridement reduces the microbial burden while facilitating antimicrobial penetration. First-line therapy are the biguanides, chlorhexidine gluconate 0.02% to 0.2% or polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) 0.02% to 0.06%, with monotherapy a consideration for early cases. For chronic or later stages, dual therapy with propamidine isethionate 0.1% or oral or topical voriconazole 1% may be needed to reduce resistance to therapy. Dosing is hourly for a continuous 48 hours, followed by hourly while awake for the next 72 hours, then q2 to q3h for three to four weeks. Dosing for the oral anti-fungal agent is 200 mg b.i.d. Response to therapy may not be apparent for up to two weeks.6 For refractory cases lasting three to four months, miltefosine (Impavido, Profounda) is an FDA-approved oral medication for Acanthamoeba keratitis dosed at 50 mg t.i.d. and continued until resolution of the keratitis.7

Concomitant severe inflammation can present as a sterile hypopyon, synechiae formation and scleritis (most commonly inflammatory instead of infectious scleritis). Adjunctive use of oral NSAIDs, immunosuppressive drugs and judicious use of steroids may be indicated. Case reports reveal some success with phototherapeutic keratectomy and cross-linking, but further studies are needed to demonstrate efficacy. In these cases of severe inflammation, the duration of treatment is prolonged from three to 12 months, and recurrences have been reported up to three months after treatment cessation. Acanthamoeba eradication is difficult to assess because it’s indistinguishable by PCR, and dead and viable cysts are both visible on confocal microscopy. Therefore, repeat cultures, scrapings and biopsy may be needed. Of note: There is a minority of cases in which Acanthamoeba are polymicrobial with concomitant HSV or fungal keratitis, so clinical suspicion should remain high when assessing response to therapy.6

Close monitoring is required to assess response to empiric antibiotic use. Up to 94 percent of bacterial ulcers will resolve.4 If there’s no clinical stability by 48 hours or improvement within four to seven days, further evaluation is recommended. A lack of clinical stability could be medication non-compliance, incorrect empiric drug choice or frequency, or a polymicrobial infection. Repeat stain and culture can be performed while on the current regimen or after cessation of antibiotics for 12 to 24 hours. To obtain a specimen that might be embedded deeper in the cornea, a braided (e.g., 7-0 or 8-0 vicryl or silk) suture can be passed through the abscess. A biopsy of the cornea may be needed to submit a specimen for histology and microbiology. With this technique, a 2 mm to 3 mm diameter dermatic punch is used to construct a partial thickness trephination to extract a strip of affected corneal stroma.3

Achieving Success

Infectious keratitis is an ophthalmic emergency that can progress to significant visual impairment from corneal melt and scarring. Even worse, endophthalmitis, perforation and loss of intraocular contents can occur. For these severe cases, temporizing measures during this infectious and inflammatory phase are required to delay deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty, or optical penetrating keratoplasty should be performed to avoid graft failure. Adjunctive measures to secure the structure of the cornea may require cyanoacrylate sealant, amniotic membrane grafting, and tectonic or therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty. With high suspicion, immediate introduction of treatment, judicious guidance from the microbiology laboratory, and excellent follow-up and patient compliance to management, complications from microbial keratitis can be mitigated.

Dr. Mah is director of the Cornea and External Disease department, and co-director of Refractive Surgery, at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla.

1. Khor W-B, Prajna VN, Garg P, et al. The Asia Cornea Society infectious keratitis study: A prospective multicenter study of infectious keratitis in Asia. Am J Ophthalmol 2018;195:161–70.

2. Ung L, Bispo PJM, Shanbhag SS, Gilmore MS, Chodosh J. The persistent dilemma of microbial keratitis: Global burden, diagnosis, and antimicrobial resistance. Surv Ophthalmol 2019;64:3:255-271.

3. Lin A, Rhee MK, Akpek EK, Amescua G, Farid M, Garcia-Ferrer FJ, Varu DM, Musch DC, Dunn SP, Mah FS; American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern Cornea and External Disease Panel. Bacterial keratitis preferred practice pattern. Ophthalmology 2019;126:1:P1-P55.

4. Moshirfar M, Hopping GC, Vaidyanathan U, Liu H, Somani AN, Ronquillo YC, Hoopes PC. Biological staining and culturing in infectious keratitis: Controversy in clinical utility. Med Hypothesis Discov Innov Ophthalmol 2019;8:3:145-151.

5. Hau SC, Dart JK, Vesaluoma M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of microbial keratitis with in vivo scanning laser confocal microscopy. Br J Ophthalmol 2010;94:8:982–7.

6. Lorenzo-Morales J, Khan NA & Walochnik J: An update on Acanthamoeba keratitis: Diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. Parasite 2015;22:10.

7. Hirabayashi KE, Lin CC, Ta CN. Oral miltefosine for refractory Acanthamoeba keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep 2019;16:100555.