Despite LASIK’s accuracy, enhancements simply come with the territory. Every once in a while a target is missed or a patient from years ago will show up with visual complaints and refractive surgeons must consider time, technique and potential risks of retreatment. We asked some veteran refractive surgeons for their insight and pearls for these rare but unavoidable situations.

Reasons for Enhancements

Enhancements typically fall into two categories: early and late. Early enhancements take place within the first few months of the initial LASIK procedure, usually due to a refractive miss that was noticed quickly following surgery. Late enhancements happen years down the line as a result of changes in the patient’s natural lens.

Regarding early enhancements, “If the patient’s unhappy with their vision in the early postop period, and you missed the target by 0.75 to 1 D, our objective at that point is to get them through that period,” says Scott MacRae, MD, the director of refractive services in the department of ophthalmology at the University of Rochester. “Many times we’ll fit them with a soft contact lens so they can see better, particularly for patients who are overcorrected and hyperopic in the presbyopic age group. Those patients can really struggle, but fitting them with a hyperopic soft contact lens in that early postop period can help them get back to a much more functional state for going back to the office/daily activities. We try to nurse them through that two to three month period.”

Reliable measurements are critical in this early enhancement phase, continues Dr. MacRae. “If somebody’s really having a hard time, you could consider retreating at two months postop but you probably want two or three measurements before you actually go ahead and do your retreatment, particularly in patients who don’t have a real clear endpoint. Sometimes they’re still changing. That’s more true for dry eyes and hyperopic correction than with myopic correction. Usually myopic correction is relatively stable after the first week or two after the dryness issues clear up,” he says. “If the patients are still dry at two or three months postop and you’re not getting reliable refractions, make sure that you aggressively treat the dryness before you get your final numbers and proceed with retreatment.”

|

|

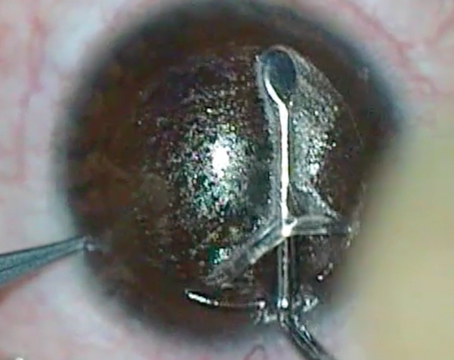

Figure 1. In his “Dry and Depress” technique for lifting a LASIK flap, Richard Mackool, MD, uses a dry sponge and gently presses on the central cornea until he spots the flap. |

Sometimes, the neuroadaptation of the patient needs to be considered and explained. “My tendency is that if the patient is 20/happy and I’m really close to the target, then I don’t encourage the patient to have retreatment unless they’re really insistent,” says Dr. MacRae. “If they’re insistent, then there are some tricks to that. Typically I’ll go ahead and refract them myself, or have my trusted staff refract the patient. Then we put that prescription into a spectacle trial frame and actually have the patient look at the difference compared to their uncorrected vision in each eye. If they notice a pretty significant visual improvement subjectively then I’ll go ahead and retreat, even if it’s relatively minor.

“The optics are more complicated than just simple numbers—there’s image quality, which can be affected by higher order aberrations or other subtleties that the patient is perceiving,” he continues. “Certain patients are much more neuroadaptive to their vision than others, so some patients can tolerate a small amount of refractive error, while other patients are really insistent that their image quality isn’t good enough and they want an improvement.”

Setting them up in a spectacle trial can be helpful in comparing each uncorrected eye to the best corrected vision with the trial lens. “If they don’t notice a difference, then I say, ‘If we try to go back and retreat, I don’t think it’s going to make any improvement,’ ” says Dr. MacRae. “Sometimes that’s enough for the patient to say, ‘My vision is pretty good. I’m happy. The doctor tried to do everything they can to get me the best vision I can get and I can settle for this.’ Doing the trial lens is actually really helpful because it avoids that situation where you go ahead and retreat, but then the patient doesn’t notice any difference and you’ve gone through this whole process. It really saves everybody time.”

In cases of late enhancements, Louisville, Kentucky’s Asim Piracha, MD, says, “You have to consider why they need an enhancement two, three or five years later. It’s not that the LASIK ‘wore off’ or that the initial treatment didn’t work—it’s that something has changed to make them either myopic or hyperopic. For myopes, it’s even still more uncommon because their vision is pretty stable long term, and for hyperopes, they tend to get a bit more hyperopic over time. So, if you have a hyperope, usually they have a lot of accommodation and, as they get older, they lose accommodation which makes them more hyperopic. This may be the reason for the enhancement.”

|

|

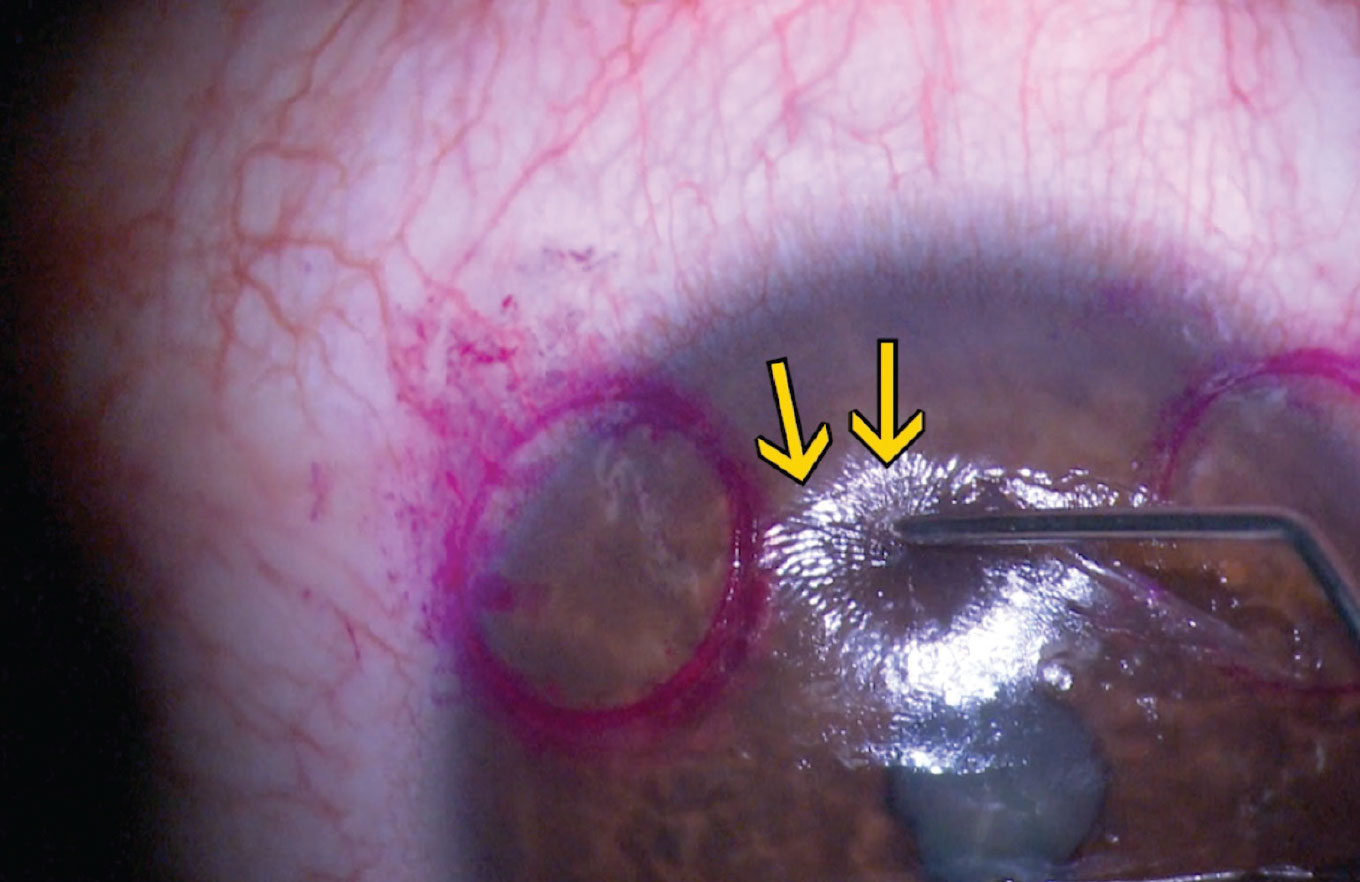

Figure 2. Scott MacRae, MD, developed an instrument called the MacRae Flap Flipper that allows him to gently lift and separate the LASIK flap, which he says has made epithelial ingrowth a rare occurrence. |

Topography will reveal a wealth of information. “If they’re beyond a couple years out and they have a myopic astigmatic change, my first thought is to see if there is any ectasia,” Dr. Piracha says. “Before any enhancement you must be really careful to make sure their topography is normal and there’s no sign of even subtle ectasia. We like to look at the preop topography and postop topography to see what’s changed. If there’s any progressive myopia, astigmatism or steepening of the inferior cornea, bullous keratopathy on the surface or posterior surface, then we’re concerned about ectasia.

“For those patients you have to be cautious and have them come back in six months and make sure there are no progressive changes,” he continues. “If it’s completely stable and there’s any concern at all about ectasia, then I would only enhance with surface ablation, I wouldn’t lift the flap. If there are signs of ectasia progression I wouldn’t enhance them at all and I would do a cross-linking treatment to stabilize the cornea and then consider going back and doing a surface treatment to enhance them (ASA or PRK) once they’re stable, which I’m pretty cautious in waiting at least a year but ideally 18 months after cross-linking before doing any enhancement.”

Dr. Piracha takes a different approach if the patient is hyperopic. “Usually it’s not a sign of ectasia,” he says. “Typically it’s a loss of accommodation as they get older or their near vision is an issue. If they’re over 40 and hyperopic I’d possibly offer an enhancement, monovision or even a refractive lens exchange to enhance them vs. laser vision correction. In all patients after 40 and definitely after 45, I do wavefront measurements on the iTrace of their eyes and look for any dysfunctional lens syndrome—aberrations in the cornea vs. aberrations from their natural lens. That influences whether we pursue a lens exchange or not.”

Cataract development could also be contributing to their vision changes, notes Dr. MacRae. “If it’s an early cataract and we think that it’s progressing, we’ll recommend waiting for six to 12 months and seeing whether their refraction changes,” he says. “If the refraction is changing then it’s not a good time to go ahead and treat—you want to make sure that the refraction is stabilized. If they continue to progress and their refraction continues to change then we recommend cataract surgery or refractive lens exchange.”

Treatments and Techniques

Surgeons traditionally treat LASIK enhancements with PRK or by re-lifting the flap and ablating the bed. Whether the patient falls under the early or late enhancement category plays a major role in the decision.

“If they’re less than two years out, I typically lift the flap and enhance them,” says Dr. Piracha. “If the patient’s beyond two years there are definitely several studies and reports to show a higher rate for epithelial ingrowth.”

Dr. MacRae concurs. “I’ll go back and retreat with a flap lift up to about two years postop but avoid it after that since epithelial ingrowth is more common with flap lifting after the first few years postop,” he says. “After two years post LASIK, typically I’ll go and do PRK on a retreat. Sometimes, we’ll see patients that are 10 or 15 years postop and they still have a little residual refractive error and they come back for just a small tune up, in which case I’ll do PRK on those eyes as well.”

PRK

For his PRK retreats, Dr. MacRae has a process, beginning with an 8.5-mm corneal trephine to demarcate the epithelium he wants to remove centrally vs. what he wants to preserve peripherally. “It very accurately demarcates the edge of the epithelium that you’re taking off so you don’t have scrolls and other irregularities,” he says. He uses an 8.5-mm well filled with 20% alcohol over the area and lets it sit on the cornea for 40 seconds. “Before removing the well, I use a Weck-Cel and allow it to swell. Then I gently twirl the Weck-Cel,” he continues. “The twirling motion causes those lateral adhesions of the epithelium to continue to adhere but the vertical epithelium anchor actually breaks or dehisces, in which case you’ll have a swirl of epithelium that comes off very easily. Then, I just take a Maloney spatula and gently remove the epithelium until I get to the edge of the area.”

One of the problems with treating or retreating with PRK is that patients can get recurrent erosions from loose epithelium, says Dr. MacRae. “PRK (or LASIK) can create mild erosion symptoms from the epithelium not vertically anchoring well. On all PRK and PTK retreats that I do, I use mitomycin-C prior to inserting the TSCL. Even if there’s a 1 percent haze rate we’d rather not have to have to deal with that at all.”

If you do notice scrolling of the epithelium, or it’s breaking down and not doing well, Dr. MacRae uses a Johnston applanator to smooth and stretch the flap. “If you notice the epithelium starting to loosen, use the Johnston applanator to applanate and stretch the flap, rather than trying to stretch the flap with Weck-Cels,” he says. “This instrument is a great option with friable epithelium and eyes with unrecognized anterior basement membrane disease to avoid damaging the epithelium further.

“Following treatment or retreatment with the excimer laser, I insert a bandage soft contact lens for seven to 10 days—sometimes, we might even leave it on longer,” he continues. “We used to worry about infection with a therapeutic soft contact lens but that’s an extremely rare event, as long as the patients are treated with antibiotics and they’re well instructed in terms of good hand-washing, rinsing the eye out in the morning with artificial tears and avoiding dust and dirt for that first week. After the bandage lens is removed, we put them on Muro 128 or a generic equivalent hypertonic ointment at bedtime for two months. This prevents recurrent erosion.”

Re-lifting the Flap

However, PRK doesn’t always make sense, even for late enhancements, notes Richard J. Mackool, MD, the founder and director of The Mackool Eye Institute and Laser Center in Queens, New York, as well as a professor at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary and NYU Medical Center. “There are reasons the patient didn’t opt for PRK in the first place, including slow recovery, risk of haze and often discomfort,” he says. “The patient probably doesn’t want to go that route for retreatment.”

|

|

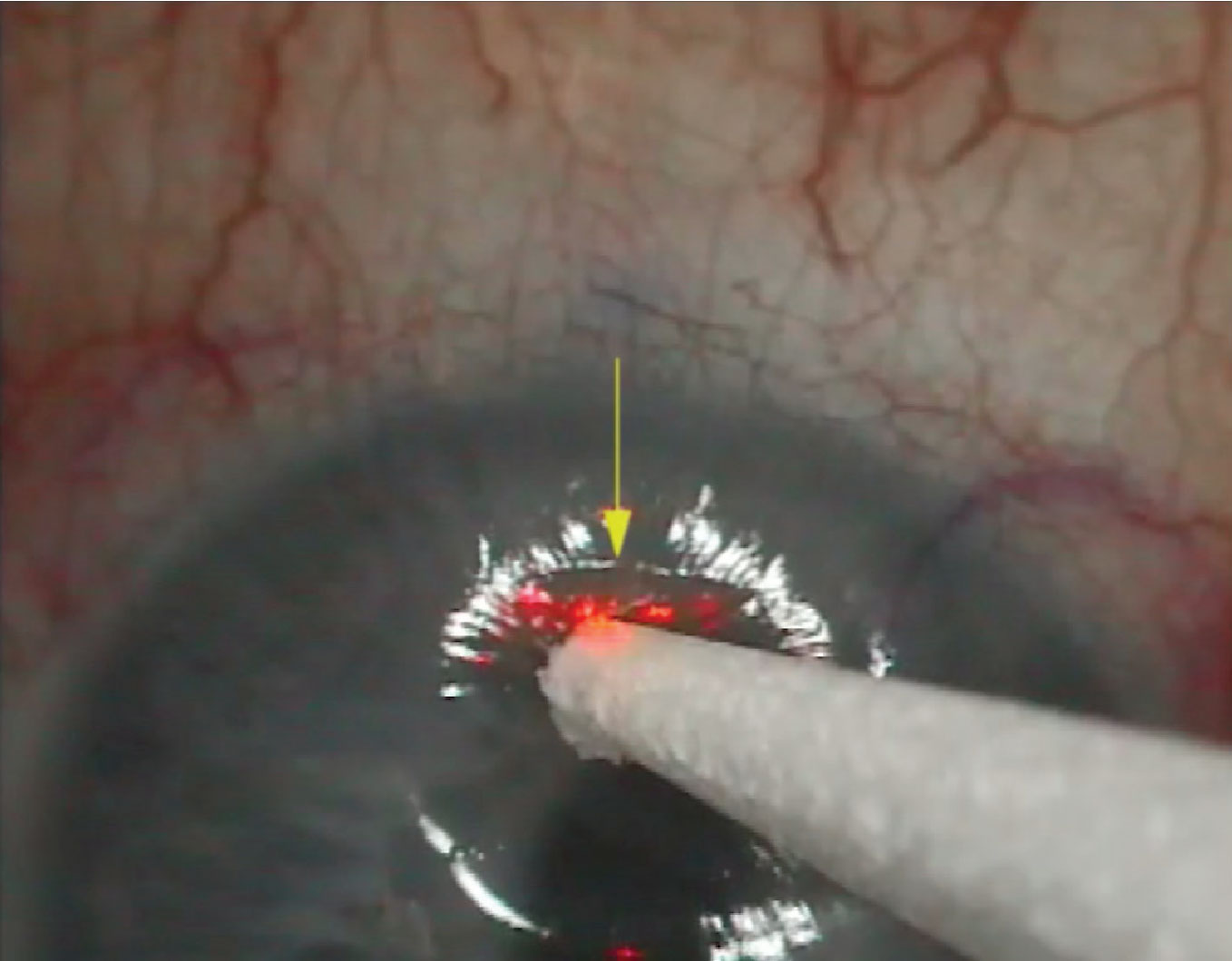

Another example of Richard Mackool, MD, finding the LASIK flap with the “Dry and Depress” technique. Dr. Mackool reports success using this technique on flaps created as far back as 29 years prior. |

Dr. Mackool developed his own flap elevation technique that has since proven successful even for a LASIK flap created 29 years earlier. Dubbed the “Dry and Depress” technique, it requires nothing more than the standard tools a refractive surgeon would already have on hand, and consists of the following steps:

• With the surgeon seated superiorly at the excimer laser microscope, the patient looks upward, bringing the inferior cornea into view. At the 8 to 10 mm optical zone, the inferior cornea is gently dried with a sponge to improve the surgeon’s ability to detect areas of epithelial irregularity, depression or elevation.

• With a dry sponge, gently depress the adjacent central region of the cornea to flatten the mid-peripheral cornea and cause the corneal light reflex to shift peripherally. Dr. Mackool says this is the ‘a-ha’ moment when you then see the junction of the LASIK flap (Figure 1).

• A blunt spatula is run back and forth along the groove, penetrating the epithelium and Bowman’s membrane, and passed beneath the flap to continue the standard flap elevation. (A video of the procedure is available below.)

“We’ve used this technique in 50 of 51 eyes (all had their original LASIK flap created by a microkeratome) that were between six months and 29 years post-LASIK. In one eye we could not penetrate the incision, so we performed PRK,” Dr. Mackool says. “Most notably, none of these patients developed epithelial ingrowth. We believe it’s because of the minimal disruption of the epithelium, similar to primary LASIK.”

Dr. Mackool advises surgeons to take their time looking for the flap. “If you don’t immediately find it down at 6 o’clock, look a little toward 7 or 8 o’clock, or 4 or 5 o’clock,” he says. “Just do a careful examination. We find it 100 percent of the time.”

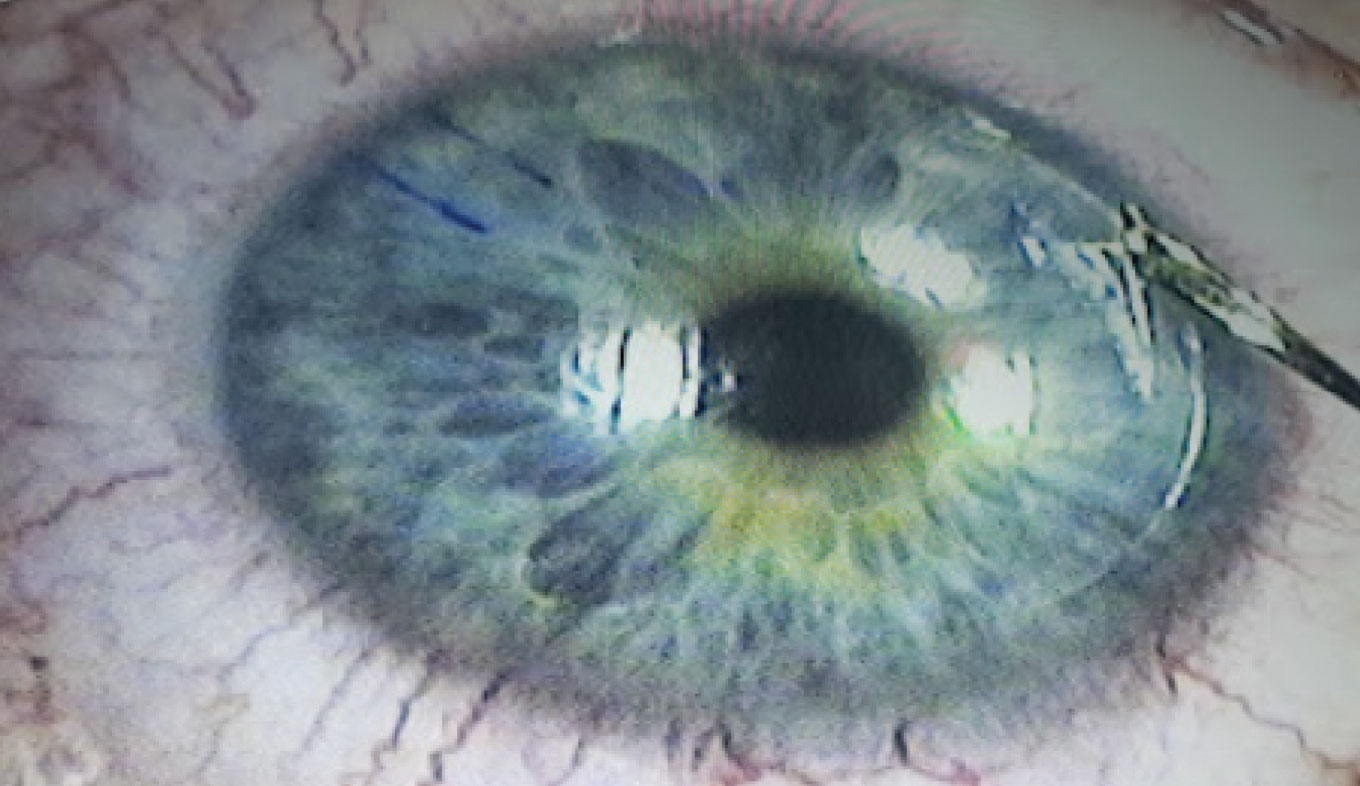

Dr. Piracha’s technique for finding the flap varies. “You can mark the edge of the flap at the slit lamp—not the laser—with a 25- or 27-gauge needle,” he says. “That way, when you lift the flap, you’re not creating a corneal abrasion. Another way is with the current lasers with a slit lamp attached, and the third way is to actually press on the cornea with a Merocel sponge and the margin of the flap shows up. At that point, I take a very fine Sinskey hook and cleanly dissect it and initiate the flap. Then I’ll take a cannula or LASIK spatula and go underneath that space and open the flap. I’m very particular about initiating that because if you’re rough identifying the margin and entering the central space from the flap, you can get epithelial ingrowth and the ingrowth can be recurrent and persistent. If it keeps returning you may have to suture the flap, which I’ve done on patients with recurrent epithelial ingrowth.”

Dr. MacRae’s flap-lifting technique was adapted from Steve Wilson, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic. “He described this technique at one of the meetings, and showed a video where he took a platypus type forceps, made a small notch at the flap edge, and then just lifted the entire flap open,” he says. “I was somewhat shocked at how quickly he lifted it. It created a really clean separation of the epithelium at the edge of the flap with very little epithelial scrolls or epithelial defects around the edge of the flap. Prior to this, I used to just push the instrument horizontally to separate the flap edge, which caused more epithelial scrolls.”

It inspired Dr. MacRae to develop an instrument called the MacRae Flap Flipper (Storz). “I score the flap edge at the slit lamp with a Sinskey hook or the Flap Flipper,” says Dr. MacRae. “The leading edge of the Flap Flipper looks like a dandelion digger that allows me to gently lift and separate the flap while moving forward and lifting around the flap edge. Dr. Wilson was absolutely correct that lifting actually separates those horizontal or lateral adhesions of the epithelium, clearly avoiding epithelial tears.”

As all of these surgeons attest, nurturing the epithelium is critical. “Epithelium tends to adhere more laterally than it does vertically where it’s anchored, so the real challenge is to get those side adhesions separated,” says Dr. MacRae. “Dr. Wilson’s technique confirms that concept that the edges are cleaner if you tug vertically as you’re lifting rather than driving horizontally. That’s actually a key to performing retreats without having epithelial ingrowth. Sparing the epithelium and epithelial defects will dramatically reduce the rates of epithelial ingrowth in my experience. Using that technique, it’s extremely rare for me to have an epithelial ingrowth. If you do see a little tag of epithelium slip into the interface after you’ve lifted, then just gently tease it back away from the interface or from the edge of the flap and tease it peripherally away from the flap margin.”

Finally, Dr. Piracha advises the close consideration for lens exchange as an alternative to PRK and lifting the flap. “You have to look at the epithelial thickness and take an OCT and explain to the patient that if we do a surface treatment, it’s going to take a long time for vision to come back, and it might be worse for the first six months,” he says. “Then you have the argument to consider a lens replacement as opposed to surface treatment. That’s an option, especially with post-LASIK IOL calculations (Barrett True-K formula) and OCT imaging, and they have several options—monofocal lenses, multifocal lenses, EDOF lenses, the IC-8. It’s appealing because you don’t have the risk of an epithelial defect and it doesn’t take long to heal.”

Dr. Mackool has no relevant disclosures. Dr. MacRae is the creator of the MacRae Flap Flipper. Dr. Piracha is a consultant to Johnson & Johnson Vision and Zeiss.