In recent years, patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy who present with symptoms such as edema, neovascularization and hemorrhages have usually been offered treatment with anti-VEGF injections. Now, trials such as PANORAMA (Study of the Efficacy and Safety of Intravitreal Aflibercept for the Improvement of Moderately Severe to Severe Nonproliferative Diabetic Retinopathy) are providing evidence that treatment before these symptoms appear may not only reduce the severity of the disease but also reduce the risk of progressing to the more-severe, symptomatic disease.

The evidence is sufficiently compelling that in May 2019 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the use of aflibercept (Eyelea, Regeneron) to treat all stages of diabetic retinopathy, including presymptomatic stages. As a result, some ophthalmologists have begun offering this treatment to patients in this category—but many others are hesitant to alter their protocol.

“Diabetic retinopathy is a heterogeneous disease,” notes Charles Wykoff, MD, PhD, director of research at Retina Consultants of Houston and deputy chair of ophthalmology for the Blanton Eye Institute at the Houston Methodist Hospital. “There’s diabetic macular edema, and then there’s diabetic retinopathy broadly.

“There are two recent studies relevant to the early stages of the disease process,” he continues. “One is PANORAMA, which is the only prospective trial giving us data about nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy eyes without diabetic macular edema in the anti-VEGF era. The other trial is the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network’s Protocol V trial, which looked at mild diabetic macular edema, when people still have relatively preserved central visual function. That trial looked at the potential value of earlier treatment with anti-VEGF injections versus laser or observation. Both of these datasets can inform clinical practice.”

|

“It’s an interesting time in terms of treatment for retinopathy regression,” agrees W. Lloyd Clark, MD, who practices at the Palmetto Retina Center in Columbia, South Carolina, and is an assistant clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine. “We now have data showing that two FDA-approved anti-VEGF agents—ranibizumab and aflibercept—can produce dramatic regression rates in a small subset of patients with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. Patients with severe nonproliferative disease receiving aggressive therapy appear to have, across the board, about an 80-percent chance of a two-step regression in retinopathy. We know this from multiple clinical trials—not just from PANORAMA, but from the registration trials for diabetic macular edema.

“This is very compelling data for a subset of patients who are at high risk of having vision-threatening complications in the next one to two years,” he continues. “It means we can potentially have a dramatic impact on the natural disease history in the 10 to 15 percent of the diabetic population with severe nonproliferative disease that we see in ophthalmic practice.”

Here, Drs. Wykoff and Clark discuss the trial data, the reasons many surgeons haven’t adopted this approach, and share their protocols for choosing patients, discussing the options with those patients, and proceeding with treatment.

What the Data Show

Among the reasons many clinicians are still not treating presymptomatic patients is that the PANORMA trial wasn’t focused primarily on the concerns and goals of clinicians. “The goal of PANORAMA was to achieve a two-step diabetic retinopathy severity score improvement, with the ultimate objective of obtaining regulatory approval for the use of a given pharmaceutical agent,” Dr. Wykoff says. “It’s helpful to understand this. In that context, a clinician’s goals aren’t necessarily about achieving a two-step diabetic retinopathy severity improvement based on color fundus photograph readings. Among other things, that doesn’t necessarily correlate with visual function.”

Dr. Clark agrees that in terms of convincing clinicians to alter their paradigm, the design of the PANORAMA trial may be part of the problem. “First of all, the trial wasn’t really designed to answer the important clinical questions that could convince patients and physicians to change their behavior,” he says. “The primary outcome for PANORAMA was a two-step regression in diabetic retinopathy severity. That’s an important endpoint, and it was critical for FDA approval, but it’s not a clinical endpoint. Most clinicians don’t use serial color fundus photographs to rate diabetic retinopathy.

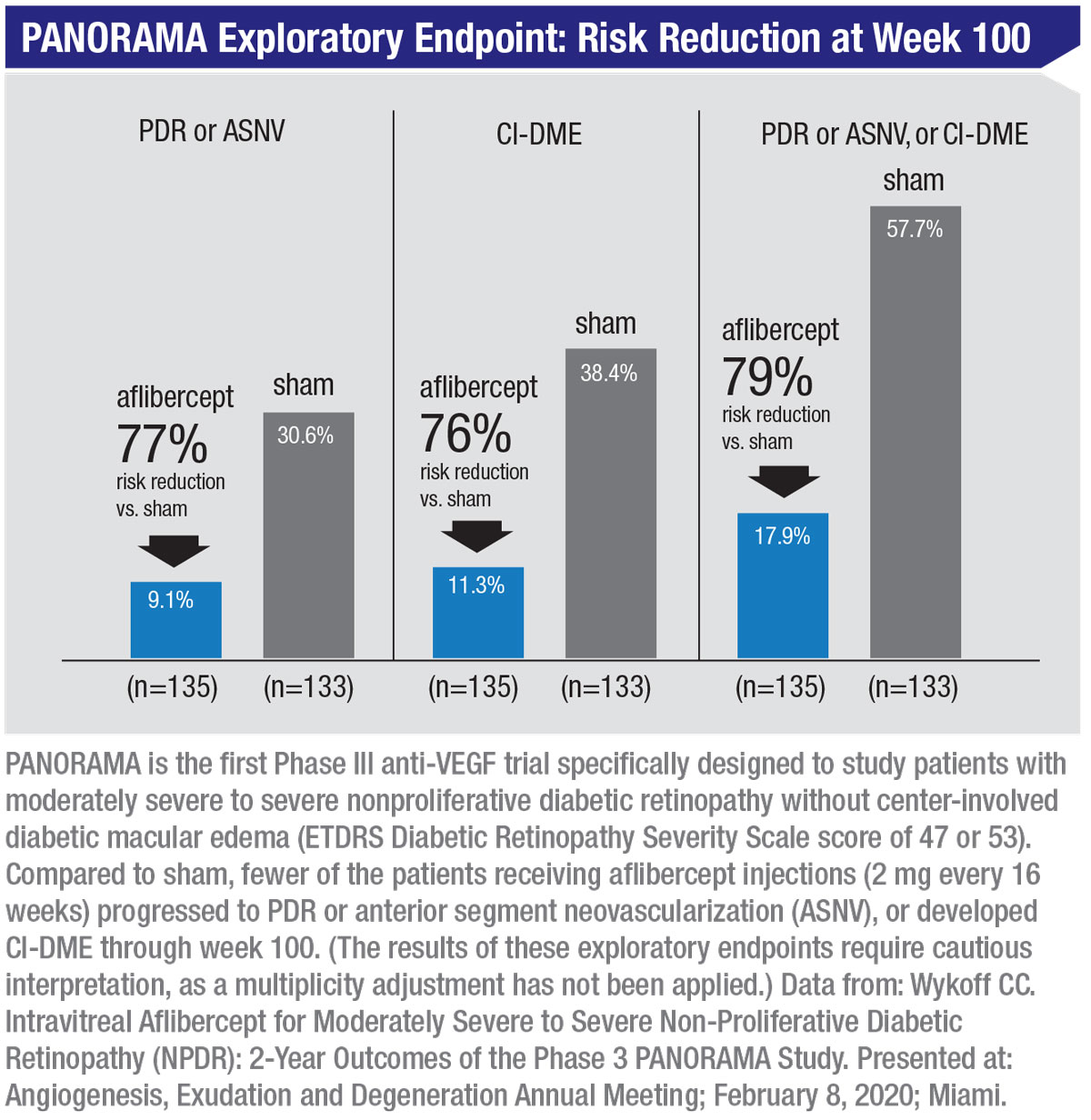

“On the other hand, an important secondary endpoint in PANORAMA was the percentage of patients that developed a vision-threatening complication,” he continues. “The complications studied in PANORAMA included the development of proliferative disease; the development of anterior segment neovascularization; and the development of center-involved diabetic macular edema. Those secondary endpoints are far more clinically relevant. Unfortunately, this was not the data that the presenters initially featured in their presentations, because it wasn’t the primary outcome of the trial.

“Now, as the discussion about PANORAMA evolves, we’re trying to change the focus to talking more about those vision-threatening complications,” he says. “The likelihood of avoiding a vision-threatening complication with either dosing strategy—as infrequently as one injection every four months—was 65 percent or higher. So even injecting the patient three times a year reduced the risk of developing one of these complications by a significant amount.

“The second issue with the clinical trial is that its design was a little confusing,” Dr. Clark continues. “The discussion during the first year of PANORAMA largely centered around the every-eight-week treatment group because that group had the highest rates of diabetic retinopathy severity regression. But in year two, the every-eight-week group was converted to treatment-as-needed. It turned out that these patients were then undertreated by the investigators, receiving fewer than two injections in the second year. As a result, the regression rates actually worsened in year two. That muddied the waters a little bit.”

Both Drs. Wykoff and Clark agree that focusing on specific parts of the trial data is more clinically helpful. “The real money lies in paying attention to the 16-week data,” Dr. Clark explains. “Only this group had fixed dosing throughout the course of the two years. These patients were treated monthly for three months, then treated three times a year thereafter, and they had about a 65-percent reduction in vision-threatening complications.

“The standard of care for a patient with severe nonproliferative disease but no symptoms,” he continues, “is to see the patient for observation every four months, based on the guidelines of the American Academy of Ophthalmology and the American Diabetes Association—just like the every-16-week group in the PANORAMA study. The only difference here, in terms of the treatment burden for these patients, is the addition of an intravitreal injection. And if they get one, their risk of developing a vision-threatening complication is reduced by two-thirds.”

Dr. Wykoff points out that the data from the second year of PANORAMA was particularly informative in regards to dosing frequency. “In the arms that transitioned to as-needed dosing, patients only got an average of 1.8 injections during the second year,” he points out. “That’s very few injections. In that context, 92 percent of the eyes maintained at least a one-step diabetic retinopathy improvement from baseline, among those who had achieved a two-step improvement at one year. In other words, once you improve your diabetic retinopathy severity with anti-VEGF dosing and achieve stability, the ongoing dosing frequency needed in most eyes, at least through one additional year, is probably very small. Every 12 or 16 weeks is probably sufficient to maintain the improvement.”

Should You Stay the Course?

Despite the new data, many surgeons haven’t altered their treatment protocols. “We know that anti-VEGF injections are highly effective at slowing the disease process,” says Dr. Wykoff. “They slow the progression of diabetic retinopathy, improve diabetic retinopathy severity levels as measured by color fundus photographs, and decrease the rates of development of proliferative diabetic retinopathy and center-involved diabetic macular edema. This has been shown by data from the PANORAMA trial, as well as other studies such as RIDE, RISE, VISTA and VIVID.

|

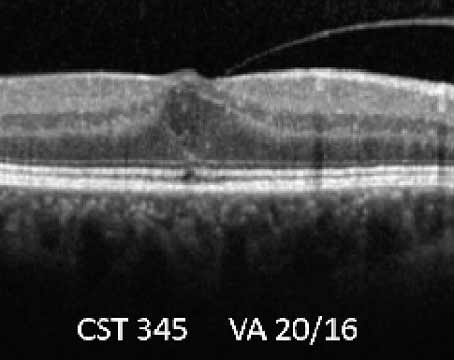

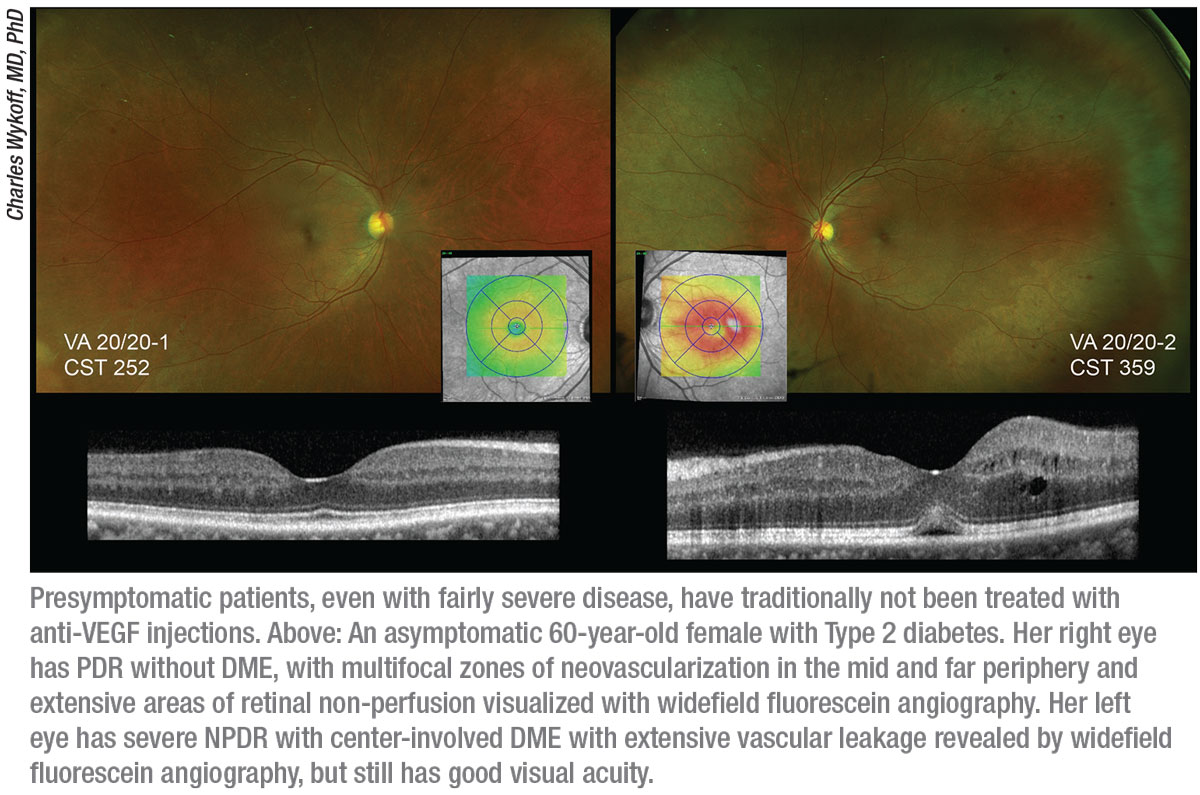

“The problem is that intravitreal injections are invasive,” he continues. “Many patients with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy without diabetic macular edema are asymptomatic. They have very good visual function. Actually, there is some evidence that they may not have totally normal visual function, even without diabetic macular edema, although we need more data to better understand this issue. But the way we currently measure visual function clinically with Snellen acuity, many of these patients have very good visual function. They often state that they’re completely asymptomatic. In that situation, it’s a high bar to start repeated intravitreal injections in most cases.

“There are certain situations in which patients may be more interested in pursuing treatment,” he continues, “such as when they’ve had complications and lost vision because of diabetic macular edema or diabetic retinopathy in the fellow eye. In that situation they may be more interested in earlier intervention to prevent disease progression. But many patients and physicians are still simply observing these high-risk nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy eyes.

“There is data to support either option,” he notes. “The data can be used to support earlier intervention, but it can also be used to support watchful waiting. Some of these eyes, as we’ve learned from both PANORAMA and DRCR protocol V, can be stable over time. As a result, following these patients closely and looking for any sign of deterioration is a very common and reasonable clinical strategy. Maintaining stability in an eye with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy without diabetic macular edema is a reasonable clinical objective.”

“I understand the resistance to this among patients and doctors when the patient doesn’t have a problem in the fellow eye or family members who’ve lost vision because of a complication from diabetes,” says Dr. Clark. “These patients have been managed appropriately for decades with close observation. If the patient hasn’t lost any vision, even at this level of severity when they might benefit from the treatment, why not maintain the status quo? Why introduce a treatment with potential complications and some additional cost, when these patients have been effectively managed in the past with observation and treatment for vision-threatening progression?

“Basically, what we’re doing here is lowering the threshold for treatment,” he says. “Instead of treating the complications, the idea is to treat the retinopathy prior to the development of complications. However, if a patient at this severity level has no vision loss in either eye, there’s bound to be some resistance to doing this. So for now, at least, I think you need a tie-breaker to proceed with therapy, be it vision loss in the other eye or a family member.”

|

Treatment Protocol

Dr. Wykoff explains his clinical protocol when managing these patients. “My personal bias is to lean toward earlier intervention,” he says. “I’d rather prevent progression of the disease and stabilize it at an earlier stage than wait for proliferative disease or center-involved diabetic macular edema and vision loss to initiate therapy. I try to achieve that goal using the least-frequent dosing possible.

“The dosing frequency in PANORAMA was substantial: five monthly doses in the Q8 arm, and three monthly doses in the Q16 arm followed by every-16-week dosing through one year,” he continues. “In clinic, when I’m treating nonproliferative retinopathy without diabetic macular edema, I often start with a less-frequent dosing pattern, such as every eight, 12 or even 16 weeks from the outset, depending on the goals and my discussion with the patient. So in the clinic we often choose to dose less-frequently than was done in PANORAMA, depending on the objectives we’re trying to achieve.”

“Of course,” he adds, “this approach is not for every patient, but it’s a discussion worth having with these patients and their caregivers.”

Would Dr. Clark consider treating patients on an eight-week schedule? “The data does suggest an additional benefit for those treated every eight weeks,” he notes. “Nevertheless, in clinical practice I’d approach this type of patient with the initial plan to pursue a dosing strategy consistent with the 16-week arm in PANORAMA. I’d have a short monthly loading period, followed by automatic extension out to four months. If the patient then developed a vision-threatening complication, I’d consider reducing the treatment interval to eight weeks. But initially I’d try to treat all of these patients every 16 weeks, because of the robust nature of the clinical trial data at two years.”

Both doctors say the patient’s situation and goals are a big part of making the treatment decision. “In most cases, patients with fovea-involving wet macular degeneration, PDR, or center-involved diabetic macular edema with vision loss are probably going to be offered treatment,” notes Dr. Wykoff. “But in earlier stages of DR and DME, it’s more of a discussion. There’s a lot to think about. What are the risks of the treatment? What are the benefits? What are the patient’s goals? What’s the patient’s ability to continue to receive ongoing close care? What’s the status of the fellow eye? Patients need to be involved in these discussions and know what the data says about their situation.

“At the end of the day,” he continues, “many patients will simply trust their physician and say, ‘What do you think?’ But along the way, most patients want to try to make an informed decision, and with these datasets we can inform them better than ever. Before this we had the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study from the 1980s, which helped us to prognosticate how eyes would do over time with different diabetic retinopathy severity levels. This newer data can guide us in terms of what the risk profile of these patients is like with and without anti-VEGF dosing.”

Dr. Clark says that in his clinic he’s opting to treat these patients—but with a few caveats. “It’s not uncommon to identify a patient with severe nonproliferative disease who’s undergoing treatment for diabetic macular edema in the fellow eye,” he notes. “That’s a pretty compelling group of patients to start with, because they already have a vision-threatening complication in one eye. In the fellow eye they have a threshold retinopathy, but without macular edema. Also, the additional treatment burden created by treating for regression in the fellow eye is minimal, because they’re already coming in for treatment of the diabetic macular edema in the one eye. You’re not going to increase the number of visits. Obviously there’s an incremental increase in risk because of the additional injection, and some incremental additional cost. But the tradeoff, in terms of risk-reduction for the fellow eye, is dramatic. You have an 80-percent chance of avoiding diabetic macular edema or proliferative disease in that eye.

“I also think this is a meaningful conversation to have when these patients, in that narrow threshold of level 47 to level 53 disease severity, have family members who’ve lost vision because of a complication from diabetes,” he adds. “I try to have a detailed discussion with these patients about the data, and they’ve indicated an interest in therapy.”

Measuring Treatment Success

One issue raised by this new protocol is that judging the success of your treatment before symptoms have occurred can be a challenge. “When managing diabetic macular edema and wet macular degeneration we have OCT,” says Dr. Wykoff. “That technology can readily show us changes in fluid status. But eyes with severe NPDR without diabetic macular edema, by definition, don’t have center-involved fluid. That means we’re relying more on other, less-quantifiable parameters such as the clinical exam.

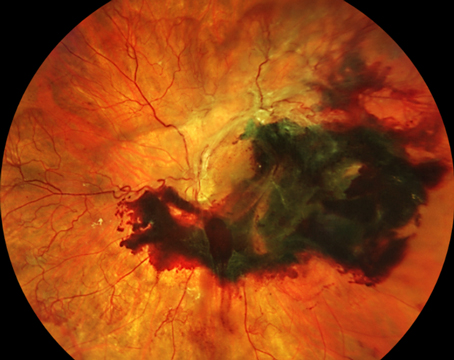

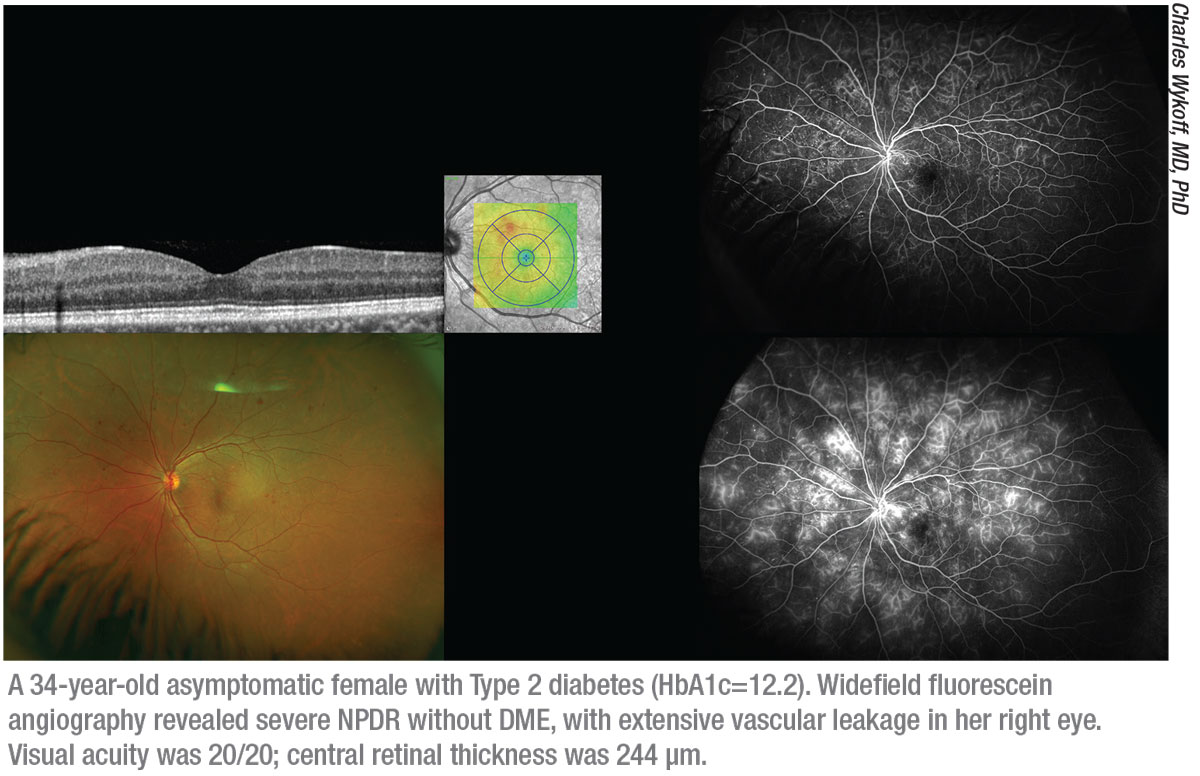

“I use a lot of fundus photography with eyes that have diabetic retinopathy,” he notes. “In my clinic I routinely use widefield imaging to manage these patients. I also like to obtain widefield fluorescein angiograms, especially at baseline. I want to know the burden of ischemia and make sure I know of any proliferative disease before initiating anti-VEGF dosing. Then, when I’m treating patients with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, I like to repeat a widefield fluorescein angiogram once a year, or once every other year. In reality, I often can’t repeat them as frequently as I would like.

“If you seldom take fundus photographs or don’t have access to such imaging,” he adds, “you’ll need to rely on clinical documentation, noting whether you think it’s mild, moderate or severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy.”

Integrating the Information

Dr. Wykoff says he doesn’t think the purpose of this data should be simply to drive usage. “The value of these datasets is to inform patients and clinicians about what to expect with patients in this disease state with various management strategies,” he explains. “They allow us to quantify the risk that the patient will end up in a specific clinical state if we do treat them or don’t treat them. That allows us to make informed decisions and recommendations. I think, towards that end, these datasets have been incredibly valuable. And, we’ll continue to learn more from them as we do more post-hoc, or hypothesis-generating analyses.”

Dr. Wykoff adds that he does see a gradual shift toward earlier treatment. “I think more doctors are considering this and discussing it with these patients,” he says. “It’s very different from center-involved diabetic macular edema with vision loss, PDR or wet macular degeneration, where most patients are going to receive treatment, and it doesn’t makes sense for every patient. It may even be a minority of patients with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy that ultimately get treated with anti-VEGF agents before they have diabetic macular edema or PDR. But I believe there’s a movement to at least consider earlier intervention and discuss it with patients, along with considering close clinical observation. As our interventional options become more durable, and hopefully—eventually—less invasive, I believe we’ll see a continued shift toward earlier intervention.” REVIEW

Dr. Wykoff is a consultant for Genentech and Regeneron and does research for both companies. Dr. Clark is a consultant, investigator and on the speaker’s bureau for both Regeneron and Genentech, and an investigator for Bayer Pharmaceuticals.