Although cataract surgery is the most common surgery being performed currently, the occasional hiccup does occur. For example, a lack of capsular support presents a challenge requiring the surgeon to determine how to fixate an intraocular lens. Common reasons for loss of support include trauma, endophthalmitis or uveitis, Marfan’s syndrome and pseudoexfoliation, to name a few.1

For decades, surgeons didn’t have many options for situations where capsular support was lacking. Today, new techniques have come to the forefront and gained widespread popularity. We asked experts to discuss their preferred methods and they shared tips and pitfalls every surgeon should consider.

Capsular Tension Rings and Scleral-Sutured IOLs

Anterior chamber IOLs, which date back to the 1950s, aren’t favored by many in modern ophthalmology due to their long-term risks of bullous keratopathy and glaucoma.2,3 Historically, one of the other popular techniques was to suture a lens to the iris with a Prolene suture. “The problem with suturing the lens to the iris is that it rubs right on the back of the iris and that chafing can also cause iritis, macular edema and pigment dispersion, and therefore it can cause clogging of the trabecular meshwork and glaucoma,” says Naveen Rao, MD, who is a cornea, cataract and anterior segment surgeon practicing in Boston. “Iris suturing may initially work for many patients, but there can be some late complications of that as well, which is why many surgeons currently opt for scleral fixation instead of iris fixation.”

Scleral-sutured IOLs have long been the chosen technique of Gregory S. H. Ogawa, MD, who practices in New Mexico. Proponents of scleral-sutured lenses note that studies have shown scleral-sutured IOLs to have a better safety profile than anterior chamber IOLs or iris-fixated IOLs.3 Scleral-sutured IOLs can reduce the risks of complications because the lens is positioned farther away from anterior segment structures.

One prevailing concern with scleral-sutured IOLs has been the risk of suture breakage. A retrospective case study reported 30 of 61 eyes needed two or more procedures due to a complication during or after the surgery, 17 of which were due to breakage of polypropylene sutures.4 Some of this concern has been mitigated with the introduction and use of Gore-Tex.

For his part, Dr. Ogawa partially attributes his preference of scleral-sutured IOLs to geography. “In New Mexico, some patients drive up to five hours from remote locations for surgery,” he says. “I take a one-and-done philosophy. If I try new techniques and they don’t work as well, my patients can’t easily come back to my office to remedy the issue. For me, scleral suturing is a bulletproof approach.”

Dr. Ogawa always uses a one-piece PMMA CZ70BD IOL (Alcon). Once he notices bad zonules, Dr. Ogawa uses capsule support hooks before carefully removing the cataract. He then makes a pair of scleral incisions behind the iris 2 mm apart and a 7-mm wide scleral groove. “I use a 2L Cionni ring, which has two suturing eyelets, and put a 1.5-cm piece of Gore-Tex through the suturing eyelet that I want to use. I usually put a 5-cm piece of 10-0 nylon through the lead eyelet—not the suturing eyelet because I want to help minimize stress on the capsular bag,” says Dr. Ogawa. “I then reach through the scleral incisions with 25-ga. curved forceps to externalize those pieces of Gore-Tex CV-8 (which is the smallest currently made) and then put a two-wrap throw.”

If the zonules are bad due to pseudoexfoliation, Dr. Ogawa will suture both eyelets.

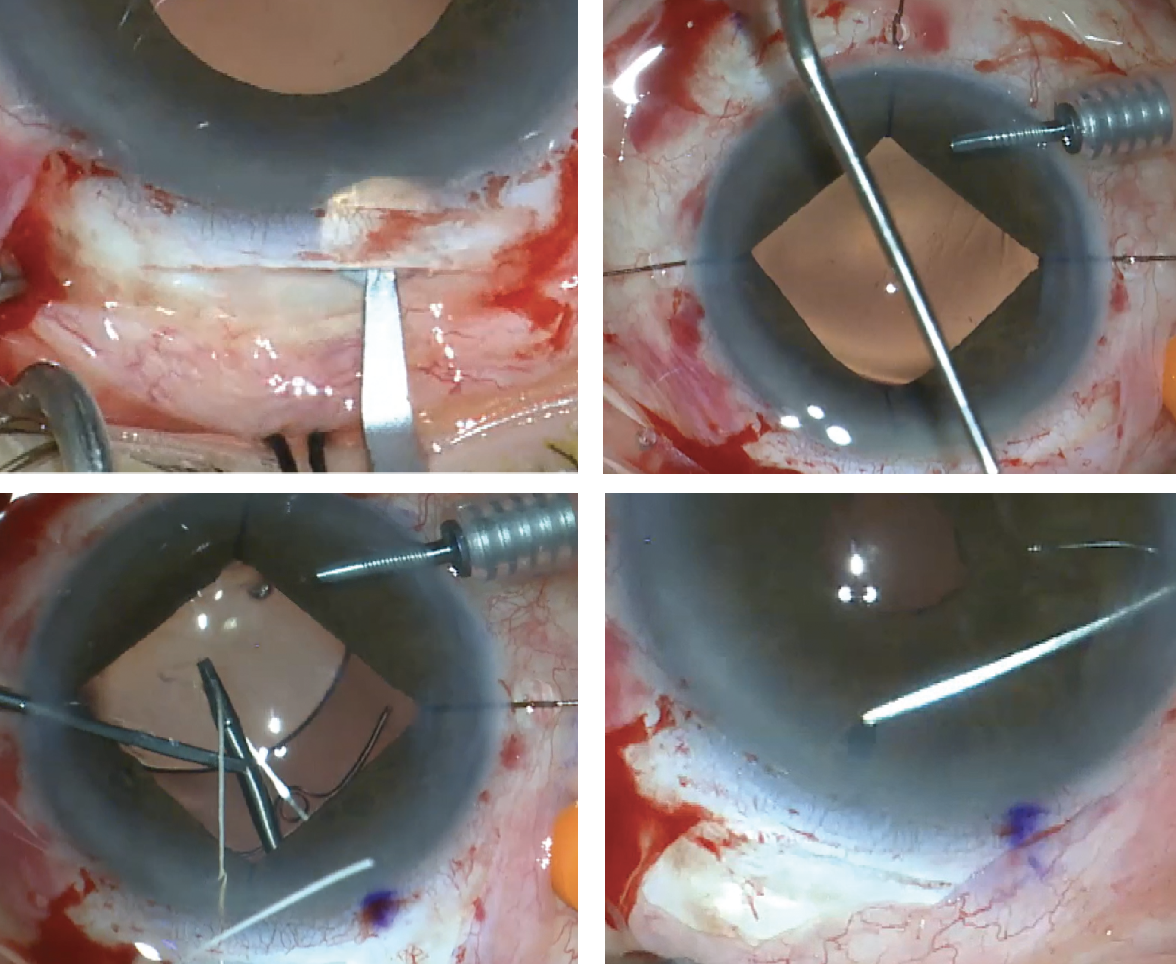

|

| Figure 1. Scleral-suture Fixation Steps: (Top left) A scleral groove is created with a tunneling blade. (Top right) One suture arm comes over through the lead haptic’s eyelet, the other between the eyelet and optic. (Bottom left) IOL placement occurs simultaneously while the straight tying forceps hold the externalized sutures. Before closing the case, intraoperative Purkinje images confirm lens centration (bottom right). (Courtesy Gregory Ogawa, MD) |

“Essentially, even if the zonules are absolutely terrible, this will support the bag,” he continues. “I place the lens implant in the bag before I remove the OVD and use a self-retaining infusion cannula at the limbus to keep things formed if need be. Then I’ll adjust the tension on the two sutures to make sure I can center things well, and then I put four single-wrap throws on both of those Gore-Tex sections. I cut the tails off the Gore-Tex and use straight tying forceps to bury the knot inside the eye. It needs to be totally inside the eye, otherwise it can erode through the conjunctiva. For this I’ll take down conjunctiva in those places and then use 10-0 vicryl to close the conjunctiva.” (Figure 1)

If a situation is particularly extreme and proves too difficult to insert a 2L ring, Dr. Ogawa will remove the capsular bag and perform an anterior vitrectomy and implant a Gore-Tex sutured IOL.

For nearly 30 years Dr. Ogawa has used this technique and the reliable, long-term results have given him no reason to adopt one of the more recently developed techniques. He estimates that he’s scleral-fixated over 2,000 IOLs, about half with Gore-Tex and the other half with polypropylene.

Although most surgeons would currently opt for smaller incisions and perhaps suture Ahmed segments with a regular CTR, Dr. Ogawa sees an advantage of a scleral tunnel with a self-sealing incision when using a 7-mm optic. “Creating that tunnel incision is something that came from the fact that I started doing eye surgery when incisions were bigger, and that might be a challenge for someone who just finished residency within the last five years and never performed a single scleral tunnel incision,” he says. “When I’m hands-on teaching this technique, we use cadaver eyes and make 15 scleral tunnels in the eye all over just to practice.”

He adds, “If speed is the most important thing, then this isn’t the technique for you. For me, the most important thing is having a good result that stands the test of time.”

Dr. Ogawa evaluated the results of 202 scleral-sutured 9-0 polypropylene posterior-chamber IOL surgeries several years ago (before the use of Gore-Tex) and the data revealed no cases of IOL tilt, suture erosion or unusual IOP elevation. Patients showed overall improvement in visual acuity, sustained IOL fixation and refractive stability and minor complications.

There are some potential risks to be cognizant of if choosing to scleral fixate, notes Dr. Rao. “The reason that a lot of surgeons don’t favor scleral-suturing is, historically, those scleral-sutured lenses were made of non-foldable PMMA plastic, which requires a big 7-mm incision. That large incision can be more of a risk, especially in older patients, including the risk of suprachoroidal hemorrhage and the requirement to use many sutures to close the incision,” he says. “There are also a variety of other strategies that can be adopted but, generally speaking, most of us don’t want to use a large incision. There are some smaller foldable lenses that can be used for scleral fixation. One of them that’s been popular with our retina colleagues is the Akreos lens, which is a foldable hydrophilic acrylic. However, hydrophilic material tends to opacify over time, especially if there are subsequent procedures that involve the use of gas or air inside the eye—and several retinal surgeries require gas and air, and several corneal procedures, such as endothelial keratoplasty, require gas and air, and that can cause opacification of this lens that’s now been sutured.”

|

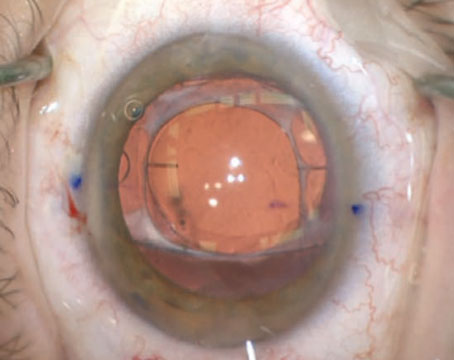

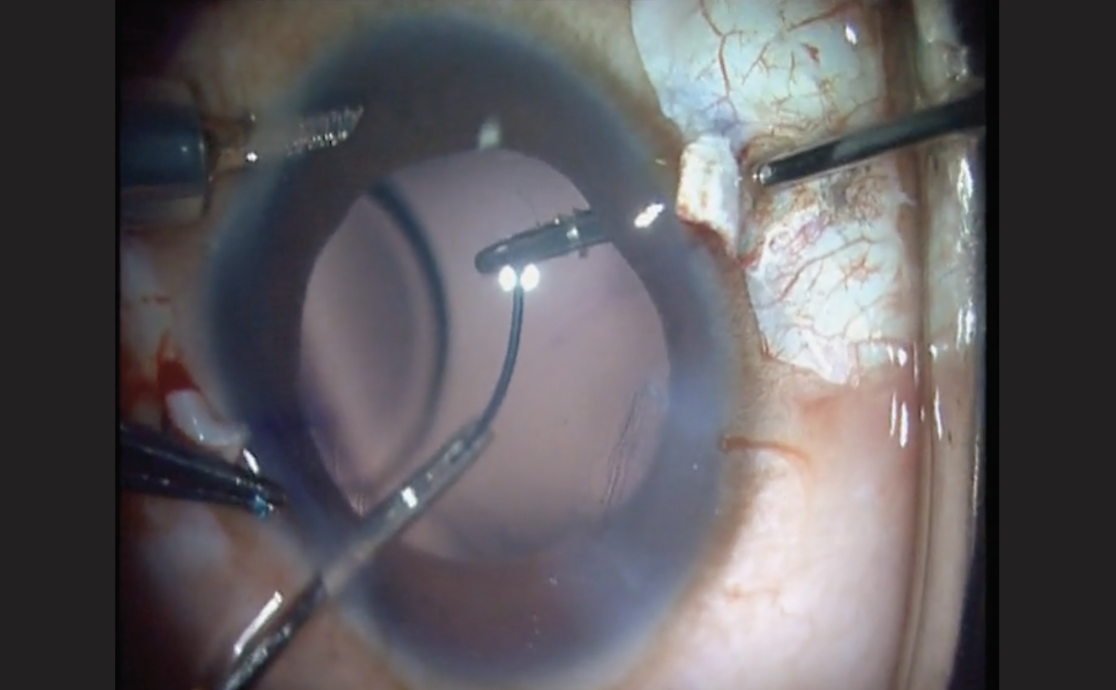

| Figure 2. Samuel Masket, MD, demonstrates the use of MST capsule support hooks to aid in the removal of a cataract before placing a capsular tension ring. (Courtesy Samuel Masket, MD) |

Samuel Masket, MD, who is a founding partner of Advanced Vision Care, and clinical professor at the Stein Eye Institute, UCLA, advocates use of the femtosecond laser, capsule support hooks and in-the-bag devices such as a capsular tension ring, Ahmed segments (CTS) and/or modified capsular tension rings (Cionni, Malyugin). “Once the capsular bag is emptied the degree of zonulopathy is assessed and appropriate capsule support devices implanted,” he says. “I also advocate careful cleaning of the anterior subcapsular lens epithelial cells in all cases at surgery to prevent fibrosis and phimosis of the anterior capsulotomy. Depending on the degree of zonulopathy, it might be necessary to perform a pars plana anterior vitrectomy.”

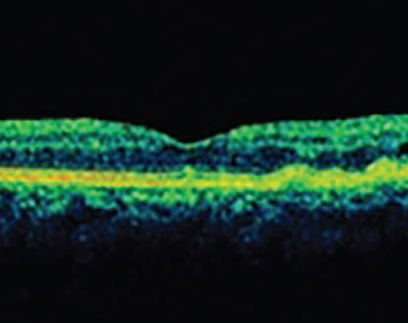

Dr. Masket was presented with a 54-year-old female patient who had sustained a bungee cord injury to the left eye that resulted in a cataract with significant zonulopathy and anterior vitreous prolapse. “At surgery a triamcinolone-assisted bimanual anterior vitrectomy was performed followed by cataract removal aided by capsule support hooks (MST),” he says (Figure 2). “Subsequently, a CTR was placed in the capsule bag and an Ahmed segment sutured to the sclera inferotemporally. During OVD removal vitreous was noted to prolapse through the main incision, necessitating pars plana vitrectomy. Five years later, the IOL capsule bag complex was noted to be stable and centered and there’s no evidence of anterior capsule phimosis.”

For patients with pseudoexfoliation with or without zonulysis needing cataract surgery it may be advisable to place a CTR at the initial surgery if a premium IOL is implanted, advises Dr. Masket. “While the CTR won’t prevent capsular contraction and late zonulysis, later on should that IOL-capsular-bag become subluxated, the CTR itself can be suture fixated to the eyewall,” he says. “This allows the bag/IOL/CTR complex to be refixated with more than two-point fixation. This maneuver can result in ‘perfect’ centration, which is necessary for a premium IOL.”

In an occasional case there will be a sufficient and stable capsule remnant that can allow the IOL optic to be captured by the capsulotomy, leaving the IOL loops anterior to the capsule while the optic is prolapsed behind a central opening in the posterior capsule, says Dr. Masket. “This creates a firm anchoring of the IOL in a simple and fast surgical approach. In some cases, a posterior capsulotomy can be sculpted with a vitrector in order to provide the scaffolding for optic capture. In those cases where optic capture of a three-piece IOL isn’t possible, iris suture fixation of the loops offers a viable alternative.”

Intrascleral Haptic Fixation

“There’s no doubt that intrascleral haptic fixation is the current method of choice for most surgeons,” says Dr. Masket. “These procedures generally take less time and require smaller incision sizes than scleral suturing methods with large PMMA IOLs.”

Intrascleral haptic fixation builds on the sutureless technique developed by Gabor Scharioth, MD, in 2006. The Scharioth technique fixates a three-piece IOL in the ciliary sulcus and the haptics in a limbus-parallel scleral tunnel or pocket. Burying the haptics reduces risks of conjunctival erosion, chronic inflammation and recurrent bleeding.5

About one year later, the first glued PC IOL implantation was done by Amar Agarwal, MD, of Chennai, India. In a “glued” IOL technique, a scleral flap covers the part of the externalized haptic and seals it with fibrin glue.6

The technique begins with corneal marking 180-degrees opposite each other for the creation of two 2.5-mm scleral flaps, followed by conjunctival peritomy and wet cautery of the sclera at the corneal marks. Two straight sclerotomies are made 1 mm from the limbus under the existing scleral flaps with a 22-ga. needle. After the vitreous is removed from the anterior chamber, a 2.8-mm corneal incision is made for inserting a three-piece foldable IOL. While being inserted, forceps pass through the left sclerotomy site and grasp the leading haptic to pull it through after the IOL has unfolded. Dr. Agarwal recommends an assistant hold this haptic tip to prevent slippage into the anterior chamber. The trailing haptic is flexed inside and its tip externalized through the other sclerotomy. Haptic tips are tucked inside a scleral tunnel, followed by a vitrectomy at the sclerotomy site, then suturing of the corneal incision with 10-0 vicryl sutures or fibrin glue. The scleral flaps and conjunctiva are then sealed with the fibrin glue.6

|

|

Figure 3. The glued IOL technique externalizes the IOL haptics through two sclerotomies and requires a “handshake” technique to transfer the tip of the trailing haptic from one set of forceps to another. (Courtesy Amar Agarwal, MD) |

Dr. Agarwal points out that the “handshake” technique—when the second haptic flexes into the anterior chamber and is grabbed by the other set of glued forceps—is an essential component of its success (Figure 3).“You’re transferring the haptic from one hand to the other until you catch it on the tip,” Dr. Agarwal explains. “Imagine if you grabbed it in the middle, the haptic has a risk of breaking. Catching it on the tip allows it to come out easily and clearly.”

Since developing this technique, this is the only one he uses for IOL fixation. In 2020, he published a retrospective case series to assess the results and complications of “glued” IOLs >5-12 years postop. Clinically, no tilt was seen in 87 of 91 eyes and no subscleral haptic was visible in 50 percent of them. The highest complication was glaucoma (7.6 percent), IOL luxation (4.4 percent) and macular edema (4.3 percent).7 In another separate study of 50 patients (25 with sutured IOLs and 25 with glued), more complications were encountered in the suture-fixation group (56 percent) vs. glued (28 percent) (p=0.045).8

Dr. Agarwal offers a few examples of candidates for the glued IOL technique. “Take a patient with a micro cornea, about 8 mm. If I put a normal 12.5-mm IOL in the bag of an 8-mm eye, the lens will never have space to open,” he says. “In this case we would use the glued IOL technique with an 8 mm IOL, but the haptics are outside, meaning the optic is 6 mm.

“If a patient has a large eye, we perform a small iridotomy in the area where the sclerotomy will bring me, coming out 1 to 2 mm from the limbus,” he continues. “I bring it out 0.5 mm from the limbus so I’m more anterior, and the more haptic I’m externalizing, the more haptic I’m tucking into the Scharioth pocket. And that is why those patients do very well.”

Dr. Agarwal says patients are very happy with this technique and notes he even performed it on his own 85-year-old mother-in-law.

The technique has become popular in the field, and Dr. Rao says it’s successful. “However, it does require a conjunctival peritomy,” he says. “Taking down the conjunctiva is a little bit time consuming and requires some scleral and conjunctival dissection. So, that has its downsides as well. There’s a little more time required because you have to then close the conjunctiva and close the scleral flaps that are made. That would be the only downside of that, although it’s a great technique.”

Dr. Masket has had complications related to the glued technique referred to him, including an extruding haptic three years postop. “With the glued IOL technique, the haptic scleral tunnel must be well constructed and of appropriate and uniform depth,” he notes.

Approximately 10 years after the glued IOL technique was introduced, Shin Yamane, MD, introduced the “flange” technique, in which the IOL haptics are cauterized at a low temperature, creating a flange that is buried in the sclera, obviating the need for sutures or tunnels. “The ‘flange’ method has also been adapted to malpositioned IOLs, employing large-bore Prolene suture material,” says Dr. Masket.

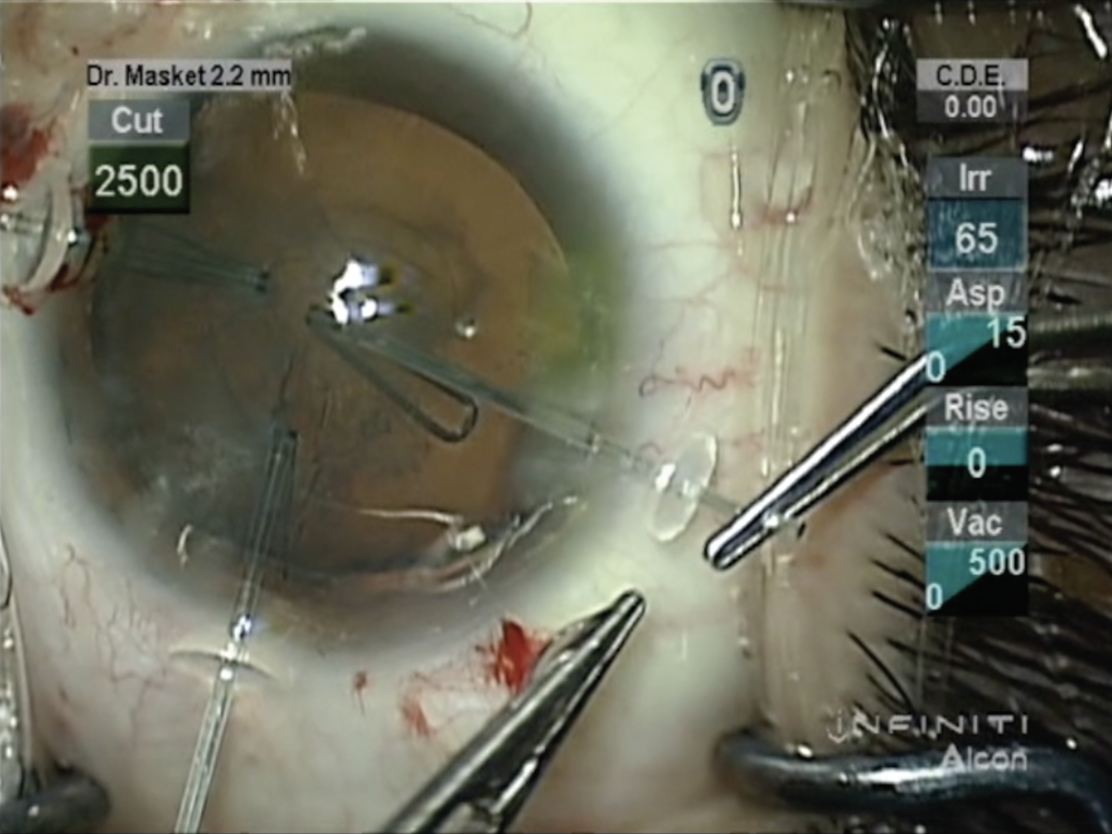

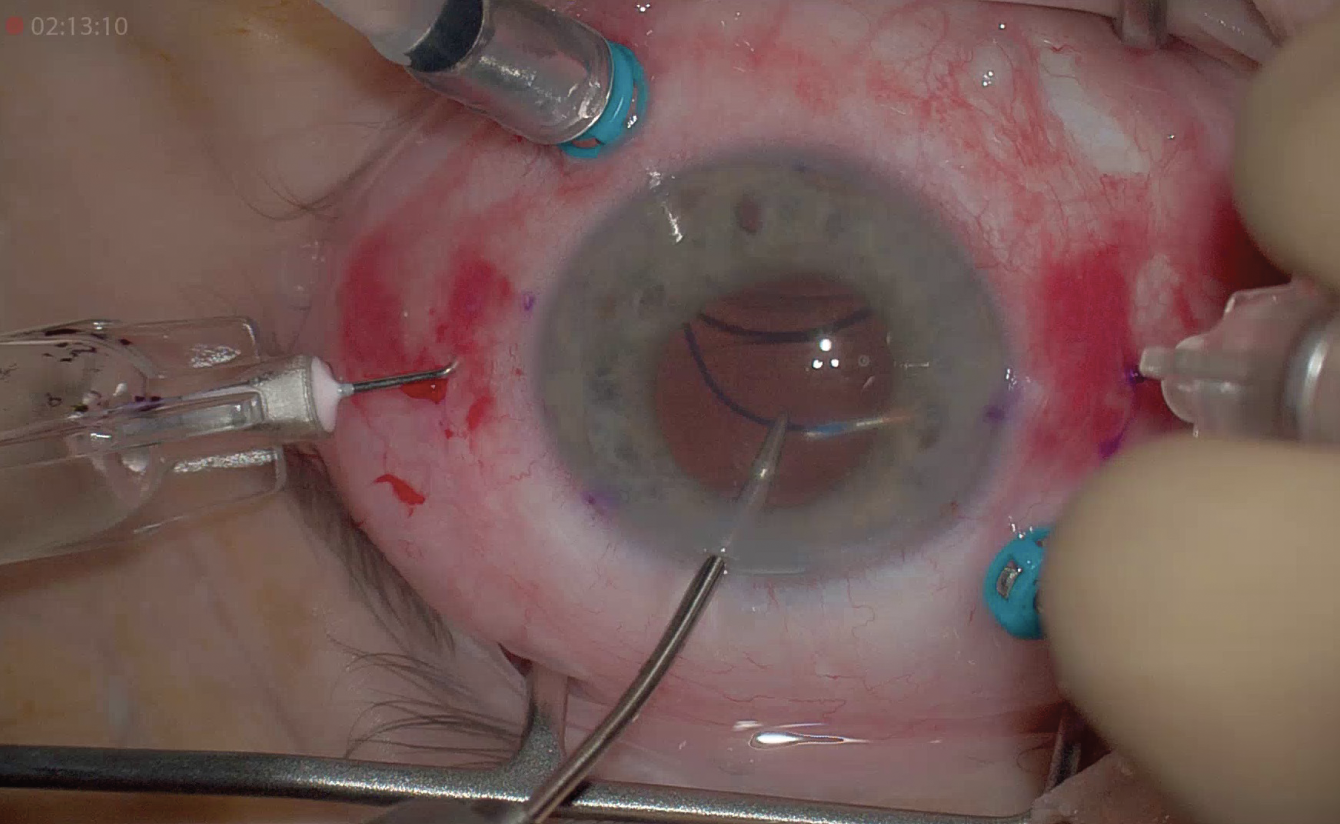

|

| Figure 4. During the Yamane technique, lens haptics are threaded or docked through two 30-ga. thin-walled needles. (Courtesy Naveen Rao, MD) |

Recognized and referred to as the “Yamane” technique, it involves two bent needles. A three-piece IOL is inserted into the anterior chamber with the trailing haptic externalized. Using a thin-walled 30-ga. needle, an angled sclerotomy is made through the conjunctiva 90 degrees from the lens incision, 2 mm posterior to the limbus. As it enters the sulcus, the needle goes toward the leading haptic, which is threaded through it with intraocular forceps. Another sclerotomy is made 180 degrees from the first, again with a 30-ga. thin-walled needle, through which the trailing haptic is threaded (Figure 4). After confirming centration of the lens, both haptics are externalized into the conjunctiva and then heated with low-temperature cautery to create a 0.3-mm flange. The flanges are tucked through the conjunctiva and into the scleral tunnels.9

“The reason the Yamane technique is so popular is because it’s very elegant,” says Dr. Rao. “It doesn’t require any conjunctival or scleral dissection. All that’s needed is the little tracks that get created in the sclera with two 30-ga. thin-walled needles. And the nice thing about it is it’s quick, it’s much less invasive and it’s compatible with a very stable lens position. Many of us have switched over to that as our primary mode of fixation when there’s no capsular support.”

Dr. Rao says the most common complication would be a decentered or tilted lens. “Once the lens has been placed in the eye and surgery is over, it’s hard to go back in there and resurrect that lens—usually that means we have to take out that lens and put in another one,” he says. “There are other risks, such as the potential to inadvertently pass the needle through the ciliary body, or if you’re not careful you could inadvertently pass the needle into the retina. I haven’t seen that complication, but that would be one concern that some surgeons have with needles that are passing in and out of the eye. Normally, we prefer to use blunt tip cannulas in the eye rather than needles. This is a unique surgery where we’re actually passing a needle inside the eye.”

“I’ve seen complications with the Yamane technique,” says Dr. Masket. “Among the concerns is that the intrascleral needle passages are ‘blind’ but need to be symmetrical and exactly 180 degrees apart in order to prevent decentration, tilt and optic capture. Perhaps using ‘on-board’ OCT can help guide the needle passes for more accurate placement.”

Dr. Rao agrees and admits the Yamane technique comes with a significant learning curve. “It’s not totally straightforward, especially for people who are doing their first few cases,” he says. “It can be quite tricky to know how to pass the needle through the sclera in such a way that the lens sits totally symmetrically and it has to be centered and it shouldn’t have any tilt to it. So there’s some difficulty there in judging the angle that the needles are tunneled through the sclera. It has to be very symmetrical. There are some tricks to do it but certainly, for the first five to 10 cases there’s a significant learning curve. Some surgeons have attempted it and then felt like it didn’t work, and it’s usually because of an asymmetry of the angle of the needle trajectories through the sclera.”

He recommends practicing at labs and on model eyes. “At most meetings, there are labs to learn this,” Dr. Rao notes. “There’s a wonderful eye model for the Yamane technique made by Simuleye, called Iris Suturing and IOL Fixation. We use this model in the AAO intrascleral haptic fixation lab, for which I’m course director. It’s a much better model honestly than pig eyes because the size and the dimensions of the eye match the size that you would need for the Yamane technique. When you use a pig eye, the problem is the lens implant that we practice with is not anywhere near the size that you need for pig eye, so the dimensions just don’t work.”

If a surgeon feels the Yamane technique isn’t working during surgery, the glued IOL is a great backup plan, says Dr. Rao. “However, fewer and fewer surgeons, at least in the United States, are learning the glued IOL technique. Most people are learning the Yamane technique, so unless someone has glued IOL training or has seen enough videos to know what to do if this happens, they may have some difficulty there. In the AAO lab for glued IOL and Yamane techniques, I like to stress to learn both, not just Yamane. I think it’s really important.”

As an instructor and surgeon adept in the Yamane technique, Dr. Rao offers some important pearls for success.

• “Always use a thin-walled, 30-ga. needle and it has to be from the manufacturer TSK, which is in Japan,” he says. “No other 30-ga. needles will work; no other thin-walled needles will work. There are other manufacturers that say they have thin-walled 30-ga. needles and I would just urge any surgeons learning this technique not to trust it—it must be the one made by TSK.”

• The preferred lens for Yamane is the Zeiss CT Lucia 602 lens. “There are some surgeons who have tried the Yamane technique with other lenses such as the Johnson & Johnson Vision AR40 or ZA9003, but I really would encourage anyone starting with this technique to start with the Zeiss CT Lucia 602 lens, which has much more resilient haptics that are made of PVDF,” Dr. Rao says. “I have no financial interest in that or at any of these products. It’s just much more versatile for this technique. The haptics of that lens can be manipulated much more than any other three-piece lens with less risk of damage to the lens.”

• Consider involving retina colleagues. “It’s really important when there’s a dislocated IOL to do pars plana vitrectomy or when there’s any complex cataract surgery and the surgeon thinks there may be any lenticular fragments that fall into the vitreous,” he says. “Those really should be cleaned out with a pars plana vitrectomy in combination with a retinal surgeon in many cases, because otherwise those lens particles can cause chronic cystoid macular edema.

“If you’re going to be going in there for the Yamane technique, try to do this in conjunction with a retinal surgeon so that a full pars plana vitrectomy can be done,” continues Dr. Rao. “I also encourage most surgeons to create a peripheral iridotomy, because sometimes with the Yamane technique, the iris can backbow postoperatively, and plaster itself against the IOL and it can cause chafing. To relieve this reverse pupillary block it’s good if surgeons create a peripheral iridotomy in any clock hour of the iris.”

Drs. Agarwal, Masket, Ogawa and Rao have no relevant disclosures.

1. Holt DG, Young J, Stagg B, Ambati BK. Anterior chamber intraocular lens, sutured posterior chamber intraocular lens, or glued intraocular lens: Where do we stand? Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2012;23:1:62-7.

2. Droutsas K, Lazaridis A, Kymionis G, Chatzistefanou K, Papaconstantinou D, Sekundo W, Koutsandrea C. Endothelial keratoplasty in eyes with a retained angle-supported intraocular lens. Int Ophthalmol 2019;39:5:1027-1035.

3. Oltulu R, Erşan İ, Şatırtav G, Donbaloglu M, Kerimoğlu H, Özkağnıcı A. Intraocular lens explantation or exchange: Indications, postoperative interventions, and outcomes. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2015;78:3:154-7.

4. Vote BJ, Tranos P, Bunce C, Charteris DG, Da Cruz L. Long-term outcome of combined pars plana vitrectomy and scleral fixated sutured posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;141:2:308–12.

5. Gabor SG, Pavlidis MM. Sutureless intrascleral posterior chamber intraocular lens fixation. J Cataract Refract Surg 2007;33:11:1851-4.

6. Narang P, Agarwal A. Glued intrascleral haptic fixation of an intraocular lens. Indian J Ophthalmol 2017;65:12:1370-1380.

7. Kumar DA, Agarwal A, Dhawan A, Thambusamy VA, Sivangnanam S, Venktesh T, Chandrasekar R. Glued intraocular lens in eyes with deficient capsules: Retrospective analysis of long-term effects. J Cataract Refract Surg 2021:1:47:4:496-503.

8. S. Ganekal, S. Venkataratnam, S. Dorairaj, V. Jhanji. Comparative evaluation of suture-assisted and fibrin glue-assisted scleral fixated intraocular lens implantation. J Refract Surg 2012;28:249-252.

9. Gelman RA, Garg S. Novel Yamane technique modification for haptic exposure after glued intrascleral haptic fixation. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep 2019;4:14:101-104.

.png)