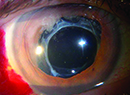

With the variety of currently available intraocular lens options, visual outcomes after IOL implantation have never been better. However, even patients with uncomplicated surgery and successful outcomes may present with complaints after surgery. These complaints typically fall into two categories: unwanted visual images and residual refractive error or poor quality of vision.

Unwanted visual images typically resolve without treatment as neuroadaptation occurs, while residual refractive error and poor quality of vision may require additional procedures.

Unwanted Visual Images

Unwanted visual images after IOL implantation can include halos at night, temporal shadow and IOL edge glare or reflections. Randall Olson, MD, and his colleagues recently conducted a study to determine the most common complaint after uncomplicated surgery with a good visual result. "Far and away, the most important dissatisfier after uncomplicated surgery was pseudophakic dysphotopsia or unwanted images. The more unwanted images patients had, the unhappier they were," says Dr. Olson, director of the

In his study, 10 percent of patients had at least moderate unwanted images more than one year after uncomplicated surgery. More sobering, "Patients in our study were implanted with rounded-edge silicone lenses, which are the most forgiving of all lenses," he adds.

One common complaint is temporal darkness, in which patients have a sense of a grayish or blurred image in the periphery of their vision. This can occur with both multifocal and monofocal IOLs.

"Temporal darkness is least likely to occur with rounded-edge silicone lenses, but I've heard complaints of this with all lenses," Dr. Olson says. "Patients implanted with high-refractive-index acrylic lenses are most likely to experience temporal darkness. The incidence of persistent temporal darkness is probably around 1 percent, which is a fair number of people if you consider how many patients undergo cataract surgery."

Of the presbyopia-correcting IOLs, the least likely to cause unwanted images is Eyeonics' Crystalens, according to Dr. Olson. "Most people with unwanted visual images just quietly suffer," he says. "They are told that they are fine and that their vision is good. Until they are specifically asked, they don't bring up these different images. I almost have to put on the hat of being a psychiatrist rather than an ophthalmologist in these situations. The first thing you have to do is listen. I've had these patients break down in tears when they feel that somebody understands what they are going through."

David F. Chang, MD, agrees. "Sometimes, it is best just to reassure the patient that his or her experience is common and that you expect it to improve. Our ability to empathize and reassure becomes more important than a surgical or pharmacologic treatment," says Dr. Chang, who is clinical professor at the

Most IOL recipients have unwanted visual images, but they suppress them, through a process called neuroadaptation. However, some patients are unable to suppress the images. Reducing nighttime pupil size with Alphagan (brimonidine tartrate ophthalmic solution) can be helpful in patients with unwanted images, specifically those that are edge-related.

Miotics, however, do not work in all cases, Dr. Chang notes. For example, the temporal crescent first reported with acrylic IOLs often does not improve with miosis. In some patients, an IOL exchange may be the only curative course of action. In these patients, Dr. Chang recommends a silicone lens with a lower refractive index. Another option may be to implant a piggyback

"These temporal negative images may be the result of the high index of refraction of the acrylic material and the variable distance that it may sit behind the iris depending on individual anatomic factors," Dr. Chang says. "Some surgeons have postulated that filling this retropupillary space with another

Mark Packer, MD, agrees that IOL exchange is rarely required. He has been implanting multifocal lenses for more than 10 years, and he has only exchanged IOLs in one patient. "This patient was absolutely adamant that the halos were destroying his life and that he needed to have those implants out," says Dr. Packer, who is clinical associate professor, Oregon Health and Sciences University, and in private practice at Drs. Fine, Hoffman, and Packer in Eugene, Ore. "He had ReZoom (AMO) lenses, and I exchanged them for AR40s—the same platform without the multifocality. He was 20/20 uncorrected with the ReZoom lenses, and he was 20/20 uncorrected with his AR40s. However, he was J1 with the ReZoom lenses and J10 with the AR40s. He needed reading glasses, but he was happy."

Residual Refractive Error/Poor Quality Vision

Other common complaints after IOL implantation include disappointment in either the quality of vision or in the lack of ability to see without glasses. "Remedies range from correcting the residual refractive errors, such as with a laser vision enhancement, employing monovision in the second eye, or mixing a different type of presbyopia-correcting IOL in the second eye," Dr. Chang says. "An example would be to implant a diffractive multifocal IOL in a patient who had an accommodating IOL in the first eye and who was disappointed in the lack of good near vision. Mixing different IOLs is one way to gain complementary advantages that a single lens implant design cannot provide by itself."

To achieve optimal vision with diffractive multifocal IOLs, such as Alcon's ReStor, Dr. Chang emphasizes the importance of aligning the central optic of the IOL with the pupil. "In most people, the pupil sits a little more nasally than the anatomic center of the eye, so if the lens is perfectly centered in the bag, the diffractive optic and the pupil may be misaligned," he says.

He notes that Italian surgeon Paolo Vinciguerra, MD, used the Nidek OPD Scan to measure the total ocular wavefront in patients who were complaining about quality of vision after implantation of the ReStor lens and where the optic was misaligned with the pupil. After surgically recentering the lens, the measured aberrations and the patients' symptoms improved. Based on these findings, he now positions the optic of the ReStor a little bit nasally within the bag by orienting the haptics at the 6- and 12-o'clock positions. "You can nudge the lens a little bit nasally off-center, and this works very well," Dr. Chang adds.

Dr. Packer says that residual refractive error, especially residual astigmatism, is the most common cause of unhappiness after IOL implantation in his practice. "This is especially true in patients with a significant amount of astigmatism that was not fully corrected with limbal relaxing incisions," he says.

He also notes that residual refractive error is common in cataract patients who have previously undergone LASIK or RK, because of the decreased accuracy of IOL calculations after previous refractive surgery.

Patients with astigmatism that is increasing after IOL implantation may require temporary glasses while their vision is stabilizing. Patients with residual refractive error may require a refractive procedure, such as LASIK, or piggyback IOL implantation.

In people who have not had previous LASIK, astigmatism (especially against-the-rule astigmatism) is usually the cause of residual refractive error. "It tends to recur in people who are younger and have higher corneal pachymetry," Dr. Packer says. "Despite what looked like perfect limbal relaxing incisions, they may still get recurrent astigmatism. I do everything I can to try to make the limbal relaxing incisions effective. I measure pachymetry and the 10-mm zone. I cut at the 10-mm zone and at 90-percent depth. I'm constantly updating my nomogram based on experience. I just recently expanded my treatment range downward, so I'm now treating even 0.5 D of astigmatism. Despite all that, there's still about a 5-percent rate of regression." He notes that he may have a patient who is 20/25 or 20/30 on day one after surgery. Then, six weeks later, the patient is 20/50 or 20/60 with 1.5 D of astigmatism that has returned. Because piggyback lenses cannot correct astigmatism, these patients are candidates for LASIK.

On the other hand, if the patient has a purely spherical refractive error with no remaining astigmatism, he or she may be a candidate for either LASIK or a piggyback IOL. Dr. Packer says that he considers a number of factors when making this decision. First is the ocular surface condition. "If patients have a tendency toward dry eye, then I might shy away from LASIK because that could exacerbate those symptoms," he explains. "However, if a patient has had previous corneal surgery, I tend to favor a piggyback IOL. Corneas that have already undergone refractive procedures are unpredictable. The final consideration is cost because it is much less expensive to do LASIK than to do a piggyback IOL."

Additionally, he explains that LASIK is more precise than a piggyback IOL because IOLs only come in 0.5-D steps.

David Hardten, MD, who is in private practice at Minnesota Eye Consultants in

Ocular Surface Issues

Although they are less likely to cause significant complaints, ocular surface issues can cause unhappiness immediately after IOL implantation. Patients may experience subclinical cystoid macular edema or dry eye.

"Dry eye is treatable and is an often-overlooked cause of a subtle decrease in visual quality," Dr. Chang says. "This is especially important with multifocal lens implants, because patients implanted with these lenses already have to accept some optical compromises in order to gain the benefits of these lenses. This lessens our margin for error with respect to other common occurrences such as early posterior capsule opacification, a dry eye, small amounts of residual astigmatism, or a tiny bit of epiretinal membrane. Everything has to be optimal."

Dr. Hardten agrees. "Patients with the new presbyopia-correcting IOLs typically suffer more severe symptoms related to CME, dry eye and blepharitis than patients with monofocal IOLs," he says.

According to Dr. Packer, dry eye typically resolves with time. In the meantime, he often prescribes Restasis (cyclosporine A). "It is great in this population and has become my first line of treatment," he says. "If a patient complains of a sandy feeling and I examine the eye and see a little punctate keratopathy, I don't delay starting him or her on Restasis." His patients typically use Restasis for six weeks.

Although patients can experience some unwanted symptoms after uncomplicated surgery, most of these symptoms resolve with time. "Many times, the most important thing we can do is spend enough time with patients listening to and acknowledging their frustration and concern. Quickly dismissing the observations and telling patients to be happy because their surgery went well and their acuity is excellent is not going to reassure them. The process of neuroadaptation will be stymied by concerns and fears that there is still a problem that no one can explain. It helps to reassure the patient that distracting optical effects are common with the artificial lens implant and that some individuals may take longer to adapt to them. I cite the example of how children must adapt to wearing braces. It might seem impossible at first, but the best measure is patience and time," Dr. Chang concludes.