Ophthalmologists have an investment in improving vision, restoring eyesight and preventing blindness. We all do these things in our communities every day, but we know that these problems exist far beyond our own backyards. We also recognize that diseases such as cataract and glaucoma have larger impacts in parts of the world that have limited resources and access to eye care. For that reason, many of us choose to devote some of our time and resources to mission work, helping others in less-advantaged parts of the world.

Still, many ophthalmologists don’t participate in international work. Often it’s because they don’t know where to begin, or because they have valid concerns and fears that remain unaddressed. Here, I’d like to address some of these concerns and offer some assistance to any glaucoma specialists who might be considering joining this global cause.

The Changing Face of Missions

One of the most important things a doctor needs to understand about mission work in the 21st century is that it has changed in significant ways, even within the last decade or two. In the past, doing mission work often simply meant spending a few weeks in another part of the world treating patients and performing surgery. But if you want to help people in the de-veloping areas of the world today, that model of mission work isn’t going to work—especially if your goal is to help manage glaucoma.

“Missions” are changing for many reasons, including:

- the availability of information in the farthest corners of the world via the Internet, which contributes to the potential for higher expectations from patients;

- better-developed eye-care infrastructure and services (rapidly chang-ing, yet still country specific);

- increased scrutiny from ministries of health—sometimes because of poor results from other visiting groups;

- scrutiny from local providers whose practices may be dramatically affected by mission care; and

- better guidance from established agencies working on sustainability.

The short-term visit model certainly doesn’t work well for our traditional approaches to glaucoma. After a drug sample runs out, glaucoma meds may not be available over the long term, and follow-up IOP monitoring is important. The inherent risks that accompany trabeculectomies and tubes are well-known, especially in the light of inadequate follow-up. (We’re all excited about the possibility of minimally invasive glaucoma sur-gery and other techniques under development that could minimize those kinds of concerns.)

The short-term visit model certainly doesn’t work well for our traditional approaches to glaucoma. After a drug sample runs out, glaucoma meds may not be available over the long term, and follow-up IOP monitoring is important. The inherent risks that accompany trabeculectomies and tubes are well-known, especially in the light of inadequate follow-up. (We’re all excited about the possibility of minimally invasive glaucoma sur-gery and other techniques under development that could minimize those kinds of concerns.)

In the meantime, the traditional approach has dramatically limited our treatment options in a short-term mission setting. For this reason, there are cases of advanced glaucoma in this setting in which the natural course of the disease is better than treating aggressively surgically. (Poor outcomes jeopardize the clinic’s reputation as well.)

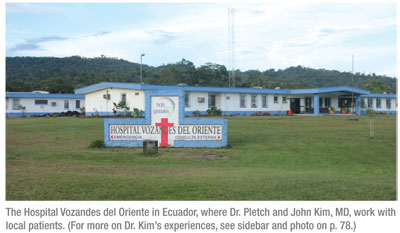

Distance is another factor that makes follow-up difficult, even if you or someone else is available to do it. We did 14 corneal transplants in Ecuador in May. Patients came from all over the country—two of them from 12 hours away on a bus. Obviously, a return visit will not be easy for these patients. We deal with that kind of concern in the United States too, but in other countries it can be far more serious; people may walk for days to reach your clinic.

Providing Help That Lasts

The best way for a glaucoma surgeon to surmount these obstacles is to focus your efforts more on collaborating—teaching and sharing techniques. Glaucoma surgery at one level or another is being done throughout the world by local surgeons. Yet few developing countries have fellowships in glaucoma. Therefore, a great way to get involved is to focus on interchange with local doctors. Those who couple with a local doctor are more likely to be appreciated.

Today, I believe some of the most effective mission work is being done by those who develop a long-term relationship with a doctor or clinic with whom they can interact over a 15- or 25-year period. That’s where real differences are being made, and that’s the direction mission work is going today.

Luckily, we’re living in an era in which it’s easy to maintain a long-term relationship at a distance, thanks to easy access to communication and information via the Internet. It’s not hard to equip your international partner with a small slit-lamp camera, allowing him to email you questions and photos during the year. That’s how many of these relationships are now functioning. You’re working together and sharing knowledge throughout the year, not just during the week or two you’re in the other country.

Interestingly, one of the side effects of the Internet’s global presence is that marketing now reaches the farthest corners of the globe. As a cataract surgeon, I’ve seen poor villagers who live in the jungle ask for a ReSTOR intraocular lens! They’ll tell you their nephew got on the Internet and re-searched the best options. I would expect the same thing to be true with glaucoma patients; you shouldn’t be shocked if someone living in poor con-ditions inquires about getting some sophisticated new type of glaucoma surgery performed.

Challenges to Face

Challenges to Face

Obviously, there can be significant challenges involved with doing international work. There are usually issues with a language barrier; you may have to work in difficult conditions; and there’s the potential for local dangers. In this post-9/11 world, Americans aren’t always welcome in some places. Furthermore, this kind of work can be psychologically challenging. You’re likely to encounter problems and levels of human suffering you might not encounter in the United States. And you’re likely to be made aware of your own limitations, which can be tough to face. You may be a terrific doctor here, but how will you fare when you’re out of your comfort zone?

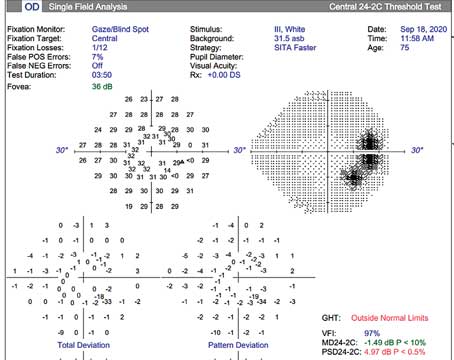

You may also be forced to work with less technology to guide you—although this isn’t always the case. One surprise we find in many rapidly developing nations such as Ecuador is the availability of OCTs, visual fields and even investigational devices that we can’t use in the United States. The downside, of course, is that these op-tions are usually only open to patients who have the resources to travel to a major city. If you’re not working in a major city, odds are good that you’ll be making judgments with less information than you would have in the United States. Furthermore, you’ll only get to see some patients once. (And they won’t have 10 years of visual fields for you to look over.)

|

As you know, making a positive impression is easier for a cataract surgeon because of the patient’s rapid improvement in vision. For that reason, the keys to doing glaucoma work will include:

- high-quality, appropriately chosen surgeries;

- appropriate follow-up, scheduled with an available ophthalmologist or other provider that you believe has adequate training; and

- the wisdom to know when the best approach is to manage medically.

If any of these key elements is missing, your outcomes will suffer and locals may not invite you to return.

Getting Started

Getting Started

Many glaucoma doctors like the idea of sharing their skills and knowledge in other parts of the world, but don’t have any idea how to begin. They may be aware of clinics in the developing world, thanks to posters at the Academy meeting and so forth, but they may wonder how to find a situation that fits their interests, skills and language limitations.

The most important key to getting involved is finding an agency you can work with that can make use of your specific skills. To that end, we’ve started a non-profit collaborative net-work called Mission Eyes Network ( missioneyes.net). Mission Eyes provides a new avenue for eye-care providers and other personnel to become involved in international missions for the poor. Our intention was to create an easier way for doc-tors to find the unique mission opportunity in which they can use their skills in meaningful ways and make a lasting difference—a central area for collaboration in which you can ask questions, find information, share experiences and techniques and make connections. In addition, we wanted Mission Eyes to be a forum for mission agencies and doctors to engage in a healthy discussion about how to improve global mission efforts—moving from the traditional “go and do” mindset to a “go, learn, support, interchange, return” model.

Mission Eyes currently represents about 20 mission agencies. You can easily connect with them, or with other doctors doing work in the field. Several hundred mission opportunities are listed. A recent addition is a Google-based mission map; using this you can search by country, agency, or the time of year you’re available. We don’t yet have a subspecialty search category based on needs, but different agencies and missions list the type of cases they’re doing, and we’re working to make the site even more helpful for subspecialists. To begin pursuing your interest in mission work, you can send an email to start a discussion; you don’t even have to log in.

In addition to Mission Eyes Net-work, helpful resources can be found at Cybersight, Orbis’s telemedicine branch, at cybersight.org. Another great resource is the Community Eye Health Journal, which can be accessed at cehjournal.org. It’s a free online journal, a collaboration of many experts who are involved in international eye care. It covers a host of issues that are specific to mission work, and many of the articles you can access relate to glaucoma care. (A recent search of their archives brought up 197 articles relating to glaucoma.)

|

So what should you be looking for? Here are some helpful strategies to get you moving in the right direction:

• Find a clinic that’s ready to use your skills. Not every clinic is ready for a glaucoma specialist. Some may still have work to do establishing a very basic level of care before they’ll be able to take advantage of your skills. If a clinic is barely getting cataract surgery done safely, that’s not a place you want to be introducing new glaucoma techniques, at least surgically. I was in Ecuador for the past year building an ophthalmology clinic. If a glaucoma specialist had called me up and said, “Hey, I want to come down and help,” I would have said no. We weren’t ready for that.

• Pick an area in which glaucoma is a major concern. For example, the incidence of glaucoma in our location isn’t as high as in some other locations I’ve visited. If our clinic were located in north Ecuador where there are a lot of people of African heritage, I’d have told that specialist, “Great! We can really use your help!” So it’s important to take local need into account.

• Identify an agency that’s experienced, and one that has a specific need for glaucoma skills. Simply joining a cataract mission may not maximize the use of a glaucoma doctor’s specific skills. So if an agency doesn’t specify that they’re looking for a glaucoma specialist, you may not be partnering with the right agency. Likewise, if you have a specific area of the world you’d like to work in, make sure the agency has experience there, and is linked with local providers and authorities. A good agency partnering with you will help you with getting through customs, getting consumables for the clinic and other practical concerns.

Of course, there may be some places in the world where there is no agency to help you. In these situations, be prepared to utilize your general ophthalmology skill set.

• Do your homework regarding the country in question. Learn a bit of the language, if you don’t already speak it. Learn as much as possible about the area’s politics, geography, history and culture. Also, find out what the current status of medical care is in the area you’ll be visiting. The more you know, the better off and more successful you’ll be.

• As much as possible, prepare yourself for the specific medical challenges and conditions you’re likely to encounter. Refresh your less instrument-based skills (for example, diagnosing without the benefit of some high-tech instrumentation). Watch videos about the situation in which you’ll be involved. Talk to others who have already worked in the area in question. If possible, visit the area with a doctor who is already familiar with it. Remember that you may be doing combined cataract and glaucoma procedures, so you’ll also need to brush up on performing manual cataract surgery. (Phaco may not be available, affordable or ap-propriate for the density of cataracts you’ll encounter.)

In some situations, you may find that you have different resources available than you would at home (as opposed to fewer). For example, you may be able to prescribe glaucoma drugs that haven’t made it through the approval process in the United States, such as combination drugs for glaucoma that blend three medi-cations in a single drop. (Part of my education during my year in Ecuador was learning about what’s available from the pharmaceutical companies in that part of the world.)

• Think about your mission as a long-term relationship and commitment to the area. I’ve seen many cases in which doctors have made this kind of commitment, and as a result made a huge difference to the people who live there over the course of 10 or 20 years. Not only does it take time to have that kind of impact, it takes time to form lasting partnerships. So it’s good to go into this prepared for the long haul.

• Make skills transfer your primary goal. That way you’ll have a far more lasting beneficial impact.

• Don’t think of your mission work as a chance to practice new procedures. This is the “I don’t feel comfortable experimenting on my patients at home, but it’s OK here” philosophy. That’s not acceptable any more. When you become part of a mission today, you want to bring to bear your best skills and knowledge. In fact, you have to be a better surgeon when you’re operating overseas in an uncomfortable environment than when you’re surrounded by all the usual bells and whistles and your favorite nurses.

Allaying Your Fears

|

One factor that clearly stops many surgeons from participating in mission work is fear, which is understandable. Most of us are aware of our limitations, and we’re concerned about causing more harm than good, especially in an uncomfortable, unfamiliar situation.

To keep your fears from being an obstacle, I recommend four things. First, talk to doctors who have already been involved in international work—the closer they are to your specialty, the better. That’s one of the ways the Mission Eyes Network website can be helpful; anyone can start a discussion about glaucoma management practices and mission work in a given country.

Second, partner with an agency that can help you manage all of the non-medical variables you’ll encounter. Then you can mainly worry about what you’re bringing to the table.

Third, consider going to the location the first time with someone who’s been doing it for a long time. I can’t think of anything more reassuring than being with someone who already knows what to expect and how to manage any problems that may arise.

Fourth, don’t go until it makes sense for you to do so. Some of the doctors I respect the most are those who say they’re not going because they’re not ready. Maybe it’s the age of their kids; maybe they feel they need to gain more skills. Even if you feel the call to go, you have to consider the whole situation, including where you are in your life and whether you’re prepared.

Glaucoma Care: A Growing Need

Although treating cataract has been a mainstay of mission work for many years, glaucoma is increasingly becoming a focus of concern for missions and international care. That’s true in part because cataract is being better managed every year, making the problems caused by glaucoma more prominent. Furthermore, as technology and information spread more rapidly, sub-specialization is increasingly appearing in the developing world. So it’s a good time for those who specialize in treating glaucoma to consider sharing their skills and knowledge with those living in less fortunate areas of the world.

Dr. Pletcher practices at Great Lakes Eye Care in St. Joseph. He founded Mission Eyes Network in 2006, and has been working in Ecuador since August 2010. He is currently starting a full time ophthalmology department at a mission hospital in eastern Ecuador. He can be reached at stan@missioneyes.net.