Any time we perform surgery that involves the cornea, we’re affecting corneal nerves, whether it’s with LASIK, PRK, cataract extraction or any other procedure. Most patients’ nerves are robust and can recover from the trauma of surgery. However, for reasons that aren’t fully understood, certain patients experience persistent symptoms of discomfort after surgery. These symptoms are often described as chronic dryness, burning, aching, tenderness and extreme light sensitivity. In the past, we lumped these symptoms under the heading of “dry eye,” but more recently we’ve recognized that these symptoms are better characterized as reflecting neuropathic pain—a distinct form of ocular pain.

Unfortunately, most surgeons don’t consider—or at least fully explore— the possibility of neuropathic pain. We tend to focus on the environment, not the nerves, meaning we exhaust all means of diagnosing various forms of ocular surface disease in a fruitless quest that ultimately leads to our patient’s continued discomfort.

To help you avoid this dilemma after LASIK, I’ll discuss how to evaluate nociceptive causes as a source of pain, and then how to move on to thinking about neuropathic causes, focusing on diagnosing and treating these patients appropriately and referring them for specialized care when it’s best to do so.

Beyond Dry Eye

Although not encompassing the type of pain patients feel from scleritis and other conditions, the word “pain” in this context reminds us that these unpleasant sensations result from nerve activation. Nerves can be activated by adverse environmental conditions, such as low tear production or incomplete eyelid closure, and we call this nociceptive pain. Nerves can also be activated inappropriately because they’re dysfunctional; this is what we call neuropathic pain.

Available data suggest that approximately 20 to 55 percent of patients report persistent ocular symptoms (lasting for at least six months postop) after LASIK surgery.1 However, it’s important to note that most individuals rate their dryness intensity as mild and report that, overall, they’re happy with the results of their procedures.

|

Surgeons naturally consider ocular surface disease as the source of symptoms of dryness, burning, aching and tenderness in post-LASIK patients. In 2015, however, we dug deeper into this issue by conducting a multidisciplinary review of available data. What we found was that the frequency and course of persistent eye symptoms after LASIK were similar to the epidemiology of persistent postop pain after other surgeries.

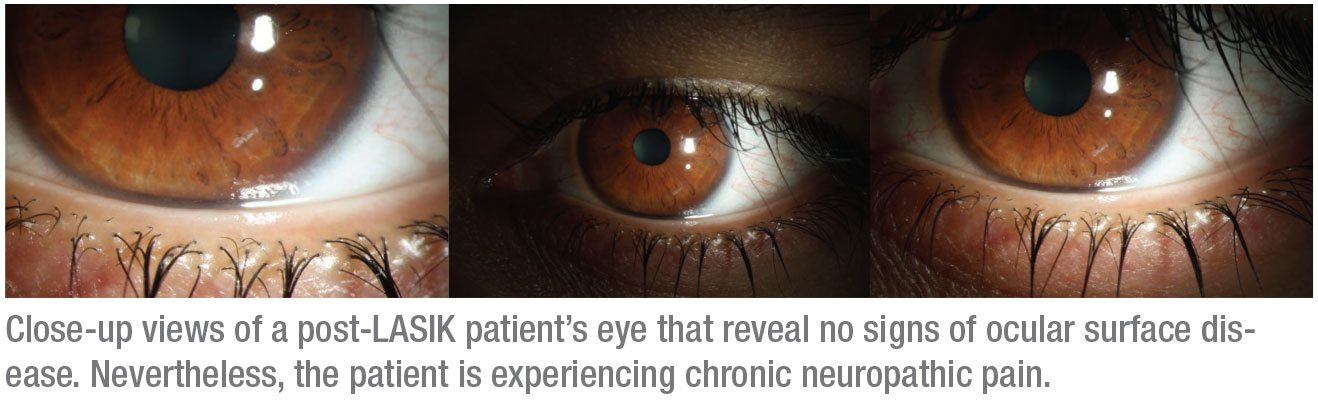

We hypothesized that pathologic neuroplasticity, both in peripheral and central nerves, was the underlying etiology of eye pain in some individuals after surgery.2 In fact, this hypothesis is consistent with similar findings in the dry-eye literature. 3 Thus, it is likely that many post-LASIK patients with chronic symptoms of dryness have nerve dysfunction as an underlying cause of symptoms. This probably explains the disconnect between patient-reported symptoms and objectively assessed tear-film findings, also seen in other “dry eye” populations outside the purview of refractive surgery.3

So the central question is this: When patients keep returning to you with ocular complaints months after LASIK, what exactly is making their nerves unhappy? Is it nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain or both?

A comprehensive ocular surface exam is vital to arriving at the correct diagnosis. This should include a symptoms questionnaire to help you determine the source of your patients’ complaints. Is it dryness, burning, or sensitivity to wind and light? Or is it vision fluctuation?

The next step is to complete an exam that focuses on nociceptive causes of pain, looking for tear-film and anatomic abnormalities. Some abnormal findings are easy to diagnose, such as low tear production or a pterygium. Others are more challenging. Causes of chronic ocular pain that are frequently missed include spastic entropion, lagophthalmos and recurrent erosions.

|

Diagnosing Neuropathic Pain

Neuropathic corneal pain can arise from tissue damage and ocular surface inflammation that’s associated with surgical trauma. The damage first causes changes in the structure and function of peripheral nerves (peripheral sensitization) but over time, central nerves can also become affected (central sensitization), with resultant pain amplification, heightened pain awareness and expansion of pain beyond the initial site of injury.3 Failure to understand neuropathic corneal pain, combined with minimal or absent clinical signs, have made diagnosis of the condition a challenge for most ophthalmologists.4,5 So: When should you consider neuropathic pain as a cause of symptoms?

• when symptoms are out of proportion to clinical examination findings;

• when pain persists after application of a topical anesthetic; and/or

• if symptoms persist despite the optimization of the ocular surface with traditional “dry eye” therapies.

A diagnosis that zeroes in on neuropathic pain is typically based on clinical history, symptoms and examination findings. Specific symptoms, such as burning and sensitivity to wind and light, are more aligned with neuropathic pain.6 Other parts of the exam include testing for persistent pain after anesthesia (e.g., the proparacaine challenge test). A positive result indicates the pain is arising from central nerves or from peripheral nerves in other locations (such as the orbit) and not from the ocular surface.

You can use in vivo confocal microscopy to evaluate the anatomy of corneal nerves. A limitation of this tool is that corneal nerve density is often persistently low after LASIK, both in those with and without ocular pain. One group of researchers found that the presence of microneuromas (abrupt nerve ending with a terminal bulb) was the best diagnostic indicator of corneal neuropathic pain.7 You can also use corneal esthesiometry (tested with cotton tip applicator, tissue, or dental floss) to qualitatively assess corneal sensitivity. Individuals with neuropathic pain often have abnormal sensitivity, which can be either decreased or increased.3

Once you conclude that nerve dysfunction may be a component of pain, prepare to move in a different direction. As someone who runs the ocular pain clinic at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Miami and who collaborates with pain specialists at the nearby University of Miami, I recommend that LASIK surgeons refer these patients for specialized care. Trying to successfully treat them is most likely not how refractive surgeons want to spend their time. (See “Ocular Pain Experts Who Can Help” above for a list of referral centers.)

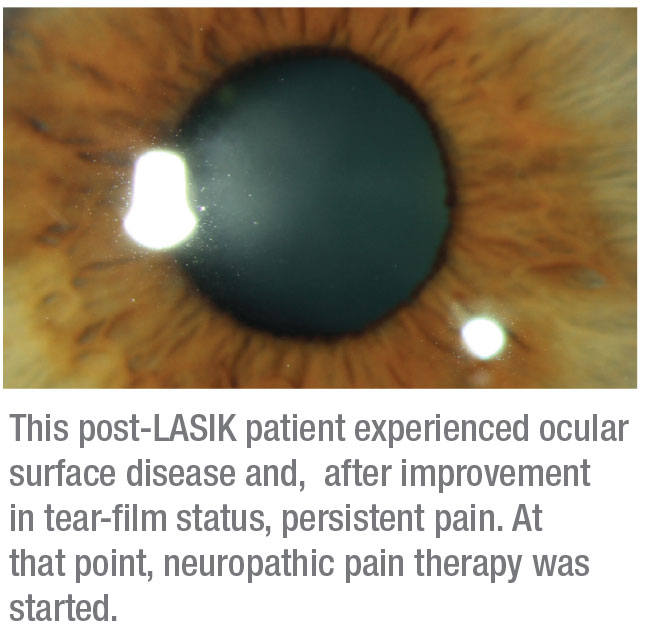

For a typical post-LASIK patient, such as a healthy 30-something, you may be ready to refer within a few weeks. But if the patient is in her 60s and presents with ocular surface disease in the form of inflammation, low tear production or fast tear breakup time, you might want to treat the unhealthy environment longer before focusing on neuropathic causes.

Along with standard dry-eye treatments—for tear insufficiency, meibomian gland dysfunction, inflammation and related issues—you can try autologous serum tears before referring one of these patients. These address both nociceptive and neuropathic components of pain.8,9 Serum tears are made from a patient’s blood and diluted in sterile saline or hyaluronic acid. The tears can introduce epithelial and nerve growth factors to the corneal surface, helping to both restore epithelial health and improve the function of abnormal peripheral nerves. If your patient’s symptoms continue after you’ve tried this treatment, your patient may require neuropathic pain therapy outside of the typical domain of ophthalmology.

|

Next Steps

In the absence of epidemiological studies, we have no documented incidence of neuropathic corneal pain. (Anecdotally, I estimate the number of patients with severe ocular pain after LASIK to be fewer than 1,000 nationally each year.) We also don’t have any FDA-approved treatments for nerve pain in the cornea. My go-to therapy includes oral medications that are commonly used to treat nerve pain outside of the eye, such as gabapentin (Neurontin) and pregabalin (Lyrica).10

I start gabapentin at a dose of 300 mg q.h.s. and slowly titrate to a dose of 600 to 900 mg t.i.d, based on clinical effects. For pregabalin, I start at a dose of 75 mg q.h.s and titrate to 150 mg b.i.d. Both medications need to be adjusted for renal insufficiency. The medications can alter mentation initially, causing patients to feel “off” or “drunk.” However, after a few weeks, this effect subsides and the medications are generally well-tolerated. If these medications prove effective, we generally continue them for two to three years and then try to titrate patients off of this therapy.

At our pain center, we treat these patients holistically. We find that patients who have symptoms of eye pain after surgery often have other pain conditions, such as fibromyalgia or migraine. We always obtain a thorough medical history and try to align our treatments to encompass all pain complaints.

We also find that the pain of many patients includes an emotional or psychiatric component.11 Chronic eye pain typically causes much anxiety. Therefore, if we see a partial response to pregabalin and gabapentin, provided the patient doesn’t have liver disease, we often add duloxetine (Cymbalta), a medication with antidepressant and anti-anxiety properties that’s also used to treat peripheral neuropathy. We start at a dose of 20 mg q.d. and titrate up to 60 mg q.d. We also work with cognitive behavioral psychologists to help patients develop active coping mechanisms.12 Other centers have had success with oral tricyclic antidepressants and low-dose naltrexone, but I have no personal experience with these therapies for post-LASIK ocular pain. Also, as needed, we’ll ask our institution’s regular pain specialist to recommend therapies that we can use.

When Therapy Fails

Not everyone responds to these measures. If necessary, we borrow pain-specialist techniques that focus on the trigeminal nerve to determine if we can change signaling from the eye. One approach is to inject periocular nerves (supraorbital, supratrochlear, infratrochlear and infraorbital) with 4 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine mixed with 1 mL of 80 mg/mL methylprednisolone acetate.10 We use nerve blocks diagnostically to determine if a patient’s pain is partially mediated by non-damaged periocular peripheral nerves, and we use them therapeutically to try to relieve pain. Botulinum toxin A injections, FDA-approved for chronic migraine, are also optional, intended to modulate trigeminal neural pathways shared with migraine pain.13

|

A non-invasive treatment that is gaining widespread acceptance is the use of transdermal electrical nerve stimulation units, an approach borrowed from our colleagues in neurology. We’ve adapted the use of Cefaly, a TENS unit used in the migraine population for treatment of ocular pain.14 Cefaly has been used to abort migraines and, in studies, has reduced the use of abortive medications such as sumatriptan by up to 50 percent. In addition, Cefaly can be used as a preventative measure to reduce the frequency of headache days per month. The small device fits on the forehead, and the patient only needs to use it for 20 minutes before going to bed each night. Studies are still needed to confirm its effectiveness in eye pain. However, our patients typically say they like the device, which they can integrate into their routines and which they subjectively say helps reduce their neuropathic pain.

Many Approaches

As you can see, addressing neuropathic corneal pain after LASIK isn’t an exact science. No therapy is the perfect therapy because many factors drive symptoms in chronic pain. The key to success is to not get stuck when your attempts to treat nociceptive pain produce no results. I’ve found that patients with neuropathic symptoms fare better if you arrange for appropriate treatment in a timely manner. The more efficiently you address this type of pain, the less likely it is to become persistent, at least in my experience, although we have no data to support this conclusion.

We can reasonably expect gradual improvement in their comfort, weaning them from medications in two or three years. There is no reason for these patients to suffer as much as some of them do. REVIEW

Dr. Galor is a staff physician at the Miami Veterans Administration Medical Center and an associate professor of ophthalmology and Cornea Co-Fellowship Director at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. She consults for Novaliq, Dompe, Allergan, Oculis and Sylentis.

1. Ambrósio R Jr, Tervo T, Wilson SE. LASIK-associated dry eye and neurotrophic epitheliopathy: Pathophysiology and strategies for prevention and treatment. J Refract Surg 2008;24:4:396-407.

2. Levitt AE, Galor A, Weiss JS, et al. Chronic dry eye symptoms after LASIK: Parallels and lessons to be learned from other persistent post-operative pain disorders. Mol Pain 2015;11:21.

3. Galor A, Moein HR, Lee C. Neuropathic pain and dry eye. Ocul Surf 2018;16:1:31-44.

4. Rosenthal P, Borsook D, Moulton EA. Oculofacial pain: Corneal nerve damage leading to pain beyond the eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016;57:13:5285-5287.

5. Galor A, Levitt RC, Felix ER, et al. Neuropathic ocular pain: An important yet underevaluated feature of dry eye. Eye (Lond) 2015;29:3:301–312.

6. Kalangara JP, Galor A, Levitt RC, et al. Burning eye syndrome: Do neuropathic pain mechanisms underlie chronic dry eye? Pain Med 2016;17:4:746-55.

7. Dieckmann G, Goyal S, Hamrah P. Neuropathic corneal pain: Approaches for management. Ophthalmology 2017 Nov;124:11S:S34-S47.

8. Aggarwal S, Kheirkhah A, Cavalcanti BM. Autologous serum tears for treatment of photoallodynia in patients with corneal neuropathy: Efficacy and evaluation with in vivo confocal microscopy. Ocul Surf 2015; 13:3:250-62.

9. Aggarwal S, Colon C, Kheirkhah A, Hamrah P. Efficacy of autologous serum tears for treatment of neuropathic corneal pain. Ocul Surf 2019;17:3:532-539.

10. Small LR, Galor A, Felix ER, et al. Oral gabapentinoids and nerve blocks for the treatment of chronic ocular pain. Eye Contact Lens 2019; Jun 14. [Epub ahead of print]

11. Crane AM, Levitt RC, Felix ER, Sarantopoulos KD, McClellan AL, Galor A. Patients with more severe symptoms of neuropathic ocular pain report more frequent and severe chronic overlapping pain conditions and psychiatric disease. Br J Ophthalmol 2017;101:2:227-231.

12. Patel S, Felix ER, Levitt RC, Sarantopoulos CD, Galor A. Dysfunctional coping mechanisms contribute to dry eye symptoms. J Clin Med 2019 Jun 24;8:6.

13. Diel RJ, Hwang J, Kroeger ZA, Levitt RC, Sarantopoulos CD, Sered H, Felix ER, Martinez-Barrizonte J, Galor A. Photophobia and sensations of dryness in patients with migraine occur independent of baseline tear volume and improve following botulinum toxin A injections. Br J Ophthalmol 2019;103:8:1024.

14. Magis D, Sava S, d’Elia T, et al. Safety and patients’ satisfaction of transcutaneous supraorbital neurostimulation (tSNS) with the Cefaly device in headache treatment: A survey of 2,313 headache sufferers in the general population. Headache Pain 2013;1;14:95.

15. Di Fiore P, Bussone G, Galli A, et al. Transcutaneous supraorbital neurostimulation for the prevention of chronic migraine: A prospective, open-label preliminary trial. Neurol Sci 2017;38(Suppl 1):201-206.