Primary selective laser trabeculoplasty for lowering IOP has become more widespread in the past few years. The laser targets the pigmented chromophores in the trabecular meshwork to produce results comparable to those of argon laser trabeculoplasty but with far less coagulative damage. Additionally, SLT can be repeated, further reducing the problem of compliance among patients who would otherwise rely on daily drops. In this article, clinicians and those at the forefront of SLT research share their experiences and offer guidance for achieving the best results with the laser.

When to Use SLT

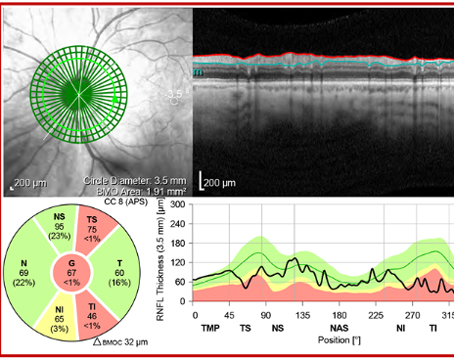

|

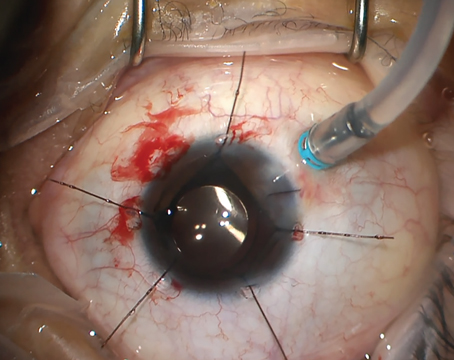

|

Gus Gazzard, MD, sets up a patient for SLT. |

SLT can be used as a primary therapy or as an adjunct treatment at any point in the glaucoma treatment paradigm, even after incisional surgery such as a tube shunt or trabeculectomy, as long as you have access to the TM. However, using it as a first-line therapy will produce the greatest effects.

“If you catch a patient early enough in mild to moderate disease stages, you may be able to delay the need for drops and also reduce the need for surgery quite significantly, within a given time frame,” says Gus Gazzard, MD, FRCOphth, director of the Glaucoma Service at Moorfields Eye Hospital and a professor of ophthalmology and glaucoma studies at University College London.

Experts estimate that SLT used as a first-line treatment can reduce IOP on the order of 25 to 30 percent, on average, with higher baseline pressures resulting in greater levels of IOP reduction. “A typical POAG or ocular hypertension glaucoma patient with an IOP in the low to mid 20s can expect around a five- to six-point drop,” says Thomas E. Bournias, MD, director of the Northwestern Ophthalmic Institute and an assistant professor of clinical ophthalmology at Northwestern University School of Medicine. “This typically occurs in 80 to 90 percent of patients. If a patient has pseudoexfoliation or pigment dispersion, you can expect a higher rate of success and greater pressure reduction. It should be done more as a first-line treatment, and we should be pushing for this more than we are.”

Patient Selection

SLT has traditionally been used when drops fail or compliance is an obstacle, but this paradigm is changing, based on new published data. “Since the publication of the Laser in Glaucoma and ocular Hypertension Trial (LiGHT) in 2019, there’s been an increasing expectation that SLT can be used first-line,”1 says Dr. Gazzard, who is also the trial’s chief investigator. “The European Glaucoma Society and the AAO’s new Preferred Practice Guidelines published this year elevated SLT from a second-line treatment to a primary first-line treatment. A recent paper also showed that well over half of glaucoma specialists routinely use SLT first-line for OAG and ocular hypertension.”

“My general approach to patients newly diagnosed with glaucoma is to look for reasons not to do SLT rather than reasons to do it,” explains Tony Realini, MD, MPH, a professor of ophthalmology and a glaucoma specialist at West Virginia University. “It’s my default, primary therapeutic option because the clinical data suggest it works at least as well as medication and that it’s at least as safe as, if not safer and more cost-effective than, medications. While we don’t have adequate instruments to measure certain glaucoma therapies’ effects on quality of life, it’s unquestionable that patients have better quality of life when off drops than on them.”

SLT is suitable for patients with mild to moderate POAG, ocular hypertension, pigment dispersion syndrome and pseudoexfoliation; even if they have some PAS. “SLT may be viable in eyes with NTG, but I don’t use it in eyes with untreated pressures less than 15 mmHg,” says Dr. Realini. “I’ve used it in eyes with steroid glaucoma with mixed success. SLT isn’t feasible, practical or indicated in eyes with angle closure glaucoma, and it’s of questionable use in eyes with inflammatory glaucoma—you don’t really want to stir up any more inflammation, although others argue there’s little harm in adding a bit more. I’ve used it in eyes when the next or alternate step was surgery, in the hopes of avoiding surgery. It’s a reasonable Hail Mary if the next treatment step is worse, but SLT isn’t my first-line in those eyes. Deal with these on a case-by-case basis, when the risk/benefit analysis favors SLT.”

“I’ve done SLT effectively on a uveitic glaucoma patient once, when we were out of options and they refused surgery, but generally they aren’t ideal candidates,” Dr. Bournias notes. “Also, avoid using SLT on patients with neovascular glaucoma or high venous pressures and those with ICE syndrome, as they have a membrane growing over the TM.”

“For very severe cases of glaucoma, it’s likely that laser on its own won’t be enough,” Dr. Gazzard cautions. “The combination of laser and drops for severe cases, and just laser for mild to moderate, is the main paradigm, and it’s very powerful.”

Patient Counseling

“I offer my patients the option of drops or laser, hoping they’ll choose laser first, for compliance reasons,” says Dr. Bournias. “If they’re unsure, we try drops. I point out that if SLT doesn’t work, it won’t cause any problems. That helps many patients feel more comfortable making the choice.

“I also tell them about the published studies,” he continues. “The Glaucoma Laser Trial in the 80s showed that patients who had laser first versus timolol averaged about a 1.2-mmHg lower pressure after seven years.2 In the LiGHT trial in Britain, 75 percent of patients who had SLT first were controlled after three years with no medication (many of these patients required only one laser treatment), 93 percent reached the target IOP and none needed glaucoma surgery over the three years, as opposed to about 11 who started with meds.”1

Patients under the age of 60 and above the age of 80 tend to choose SLT more readily, experts point out. “It’s about compliance,” says Sanjay Asrani, MD, a professor of ophthalmology at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. “Younger patients recognize that their busy schedules won’t leave time for putting in drops, and older patients may have physical or memory limitations that impair their ability to instill or remember to instill the drops. They’re also likely to be on multiple other medications, and are frequently happy not to add another.”

Dr. Asrani says patients may get lulled into a false sense of security with SLT. “They should be counselled carefully before and after that this isn’t a lifetime cure for glaucoma, but a time-limited treatment that still requires regular pressure monitoring.”

Choosing A Lens

SLT lenses are designed to minimize laser beam distortion and provide good visualization of the angle. These clinicians say they’ve used the Latina SLT lens, Magna View gonio lens, Ritch laser trabeculoplasty lens (all from Ocular Instruments) and the SLT lenses from Volk.

“We use the Latina or Volk SLT lenses because they correct for astigmatism and maintain a circular laser beam profile so you can maintain laser spot size for accurate energy delivery to the TM,” Dr. Bournias says. “SLT uses a 400-µm circular spot, and the large spot size (compared to ALT’s 50-µm spot), coupled with any corneal astigmatism, can produce an oblong shape that won’t have even energy distribution.”

“The Latina lens has one mirror and the Ritch lens has two,” Dr. Asrani notes. “I have to rotate the Ritch lens only once, whereas I rotate the Latina lens three times. The Latina lens has a smaller footprint, so it goes more easily into eyes with small palpebral fissures. I’ve been using this lens for a number of years.”

Dr. Realini notes that using the Latina lens with the rotating flange enables him to spin the lens without having to release and re-grasp it. “I can do an entire 360-degree treatment all at once, without lens manipulation-related interruptions,” he says.

Preoperative Preparation

After informed consent and instillation of a topical anesthetic, a pressure-lowering drop such as brimonidine is often instilled to reduce the risk of a post-laser pressure spike.

While some clinicians use miotics, Dr. Realini and Dr. Bournias say they don’t. “In general, a miotic will pull the lens-iris-diaphragm forward, which might inhibit access to the TM,” Dr. Bournias says. “The pupil contraction will also decrease the blood-aqueous barrier, which may lead to more inflammation.”

Dr. Gazzard says mydriatics, too, are a no-go for him. “If a patient has been dilated for an exam, I do the laser on another day,” he says. “Dilated pupils increase the risk of laser energy passing through the pupil, which can be damaging. I wouldn’t expect that to happen, but it’s a possibility.”

Prior to performing SLT, a coupling agent must be applied to the ocular surface for visualization. “I use an artificial tear gel, rather than the typical gonioscopy coupling agent,” Dr. Realini says. “It’s the same chemical, but 1/10th the concentration, so it’s far less viscous, and the lens rotates and comes off the eye more easily—it doesn’t fall off the eye during the procedure, nor do I have any problems with bubbles. The artificial tear gel is perfectly adequate for maintaining coupling during the procedure.”

Dr. Asrani says he uses Refresh Celluvisc preservative-free tears (Allergan) inside the well of the lens to prevent the patient’s having blurry vision and stickiness at the end of the procedure. Typical coupling agents such as hydroxypropyl methylcellulose can be very sticky on the ocular surface; using artificial tears can avoid this and may also be gentler on the corneal epithelium.3,4

The Full Circle

Once the patient is brought to the laser, the lens is placed on the eye to provide a magnified view of the TM, where approximately 80 to 100 532-nm laser pulses are placed, evenly spaced, 360 degrees around the angle.

Today, most clinicians treat the full 360 degrees, rather than 180 degrees, as is standard with ALT. “With SLT, we tend to get better results with 360 degrees,” says Dr. Bournias. “I try to get in about 90 to 100 spots. If the patient has PAS, I treat in-between the PAS, hoping the patient has at least 180 degrees of exposed TM.”

“Several studies show that 360 degrees is superior to 180,” Dr. Realini adds. “Why would we want to leave anything on the table when there’s no cost to finishing the full treatment in one sitting?” He notes that he’ll split the procedure into two 180-degree sessions about two weeks apart in heavily pigmented eyes at high risk for IOP spikes, such as patients with pigmentary glaucoma or those who’ve had complicated cataract surgery.

A version of the “energy technique,” proposed by Mark Latina, MD, when he first described SLT in 2002 is widely used.5 His original technique involved placing 50 spots over 180 degrees, at energy levels ranging from 0.4 to 1.4 mJ/pulse. Now, lasers are initially set at 0.8 mJ and increased or decreased in 0.1-mJ steps depending on changes in the cavitation bubbles.

“I start out at 0.8 mJ and increase or decrease the laser energy, depending upon the response,” says Dr. Asrani. “I aim for at least half of my spots having a fine, champagne-bubble appearance. I do about 75 to 85 spots per eye and space them out by one or two spot distances. I don’t start at any particular section of the angle, but when I treat the lower TM, which is reflected by the upper mirror, I typically have to lower the energy level because that area is more pigmented than other areas.

“If I’m doing SLT for the first time on a patient, I’ll typically do one eye at a time, at separate visits,” Dr. Asrani continues. “If I’m doing a repeat SLT, and I know the patient tolerated it very well last time, I’ll do both eyes on the same day.

“The advantage of doing one eye at a time is that there are no limitations for the patient after the procedure,” he continues. “They can go about their own daily activities without any restrictions, and they know what to expect when they come back for the other eye. When they come back I get a chance to see if the SLT was effective. It’s like a monocular drug trial. Typically, I’ll see a significant asymmetry of pressure, so I know the SLT works and that gives both the patient and me confidence enough to proceed with the second eye. SLT doesn’t work about 10 percent of the time, and if it fails, then I don’t do the other eye.”

“I usually treat both eyes in the same sitting,” Dr. Gazzard says. “I don’t titrate the number of shots for different sized eyes, and I usually treat the whole 360 degrees of the TM with 100 pulses. I use a very low laser exposure, around 0.3 mJ for very pigmented angles, all the way up to 1.6 mJ in very unpigmented angles that need more laser to get a result. I’m looking for a just-visible formation of champagne bubbles at the TM.”

Post Laser Care

Studies have suggested that anti-inflammatory drugs such as topical steroids and NSAIDs may help reduce the risk of post-laser pressure spikes, but Dr. Gazzard notes that such pressure spikes are rare. “They’re much less common than we thought when we first started using laser,” he says. “I recheck pressure after 45 minutes. I haven’t found that anti-inflammatory drugs help pressure response, though I do give patients an anti-inflammatory drug such as Ketorolac to use in case the eye is painful.”

“I don’t use any post-laser steroids or NSAIDs,” Dr. Asrani says. “I’ve had good enough outcomes without them, so, I put in only one drop each of brimonidine and prednisolone at the end of the laser procedure. I check patients after 30 minutes, and if the pressure rises, I check again in 15 or 20 minutes. I’ve stopped doing one-week pressure check visits. After many years I’ve found almost no one has a pressure spike one week later, so now I see them back in five weeks.”

“I also don’t use any post-laser anti-inflammatory therapy,” Dr. Realini says, who has likewise eliminated the one-week follow-up visit. “I haven’t used any in 15 years and there have been no problems. We published data from a randomized clinical trial in the U.S. on the use of steroids versus no steroids and found no differences. In the West Indies Glaucoma Laser study (WIGLS), which I ran for many years, we looked at the course of inflammation postoperatively in AfroCaribbean eyes that received SLT and didn’t receive any anti-inflammatory therapy. Inflammation postop was clinically insignificant. Of the thousands of patients I’ve treated with SLT, four have had a postop inflammatory reaction, which I subsequently treated with topical anti-inflammatory therapy. I think it’s smarter to treat the four who need it than all those who don’t. It’s expensive and comes with the hassle of more drops.”

Post laser complications with SLT are few, but there’s a small chance you may encounter a scratch on the cornea from the SLT lens. “In high myopes, there’s a very small but significant chance of corneal edema,” Dr. Gazzard adds. “I’ve done hundreds of SLTs and have only seen it in three or four patients, but it does happen. Something about the optics of the anterior segment of very high myopes seems to be the problem. I don’t think it’s related to pigmentation in the front of the eye. It may be related to the path the laser takes through the corneal endothelium. Some patients may also get an endotheliitis that lasts a few days. If that happens, I normally treat with topical anti-inflammatories or mild steroids.”

Follow-up

At the follow-up visit, clinicians check whether the patient had an IOP response. “IOP fluctuates a great deal from visit to visit,” Dr. Realini says. “The AAO recently stopped recommending the monocular drug trial as a way to measure drug efficacy when starting new therapy because it’s hard to tell on the first treatment whether or not it’s working because of pressure fluctuations. The same goes when assessing SLT.

“If I see the patient back in one month and they haven’t had the IOP response I was hoping for and they aren’t in need of urgent pressure reduction (if they are, SLT isn’t suitable), then I bring them back in another month to check pressures again,” he says. “In most cases, eyes that haven’t responded at one month respond at two months.”

If patients have responded at the one-month mark, Dr. Realini says that’s probably the IOP reduction you’re going to get. “In WIGLS there wasn’t any further reduction in mean IOP from one month to three months or twelve months. Our results have been replicated by several investigators in various African countries.”

These results are consistent with other study findings concerning SLT’s efficacy among different ethnicities. “The nice thing about SLT is that it works equally well in patients who are pigmented versus those with almost no pigment in the TM,” Dr. Bournias says. “In my 1997 AAO presentation, I presented findings that showed ALT had significantly lower success rates in African-American patients than white patients at one year follow-up (52 versus 80 percent, p<0.05).6 SLT demonstrates similar results in black and white patients.” He says this is likely due to the thermal relaxation time of melanin in the TM, which is approximately 2 microseconds. SLT’s 3-nanosecond pulse duration distributed over a 400-µm spot is too brief for melanin to transfer thermal energy. ALT is a 50-µm spot with 0.1-second constant-wave duration.

The LiGHT Trial also noted SLT’s efficacy in a diverse population. It included a significant number of non-white individuals, including South Asians, African and AfroCaribbean people and a small number of East-Asian patients. “We didn’t power the trial to look for differences among ethnicities, but we found no differences between whites and non-whites,” Dr. Gazzard says.

Retreatment

“In the same eye, I’d do a repeat SLT treatment no earlier than 18 months,” Dr. Asrani says. “If the effect wears out much sooner, the chances are the next one will wear out even sooner and it’s not worth it. Typically, I’ve seen the effect last 18 to 36 months.”

“I’ll repeat primary SLT fairly quickly if patients are highly motivated to stay off drops,” Dr. Realini says. “About 85 to 90 percent of patients respond well to first-line SLT. My impression is that about half of those who don’t respond to first-line SLT will respond to a second treatment. If we pick up that half, we’re looking at response rates in the 92- to 95-percent range with one or two SLTs. Albert Khouri, MD, published a paper that looked at whether response to the first SLT predicated response to a second SLT and found that there’s not much connection. People who had a poor first SLT response can have a great second SLT response.”

The LiGHT Trial also published a paper that found repeat SLT successful. “We showed that if the laser wore off within 18 months, repeating it seemed to be very powerful; it worked not only as well but for even longer than the first laser,” Dr. Gazzard says. “We found that 60 percent of those patients were still controlled with laser alone after another 18 months of follow-up.”

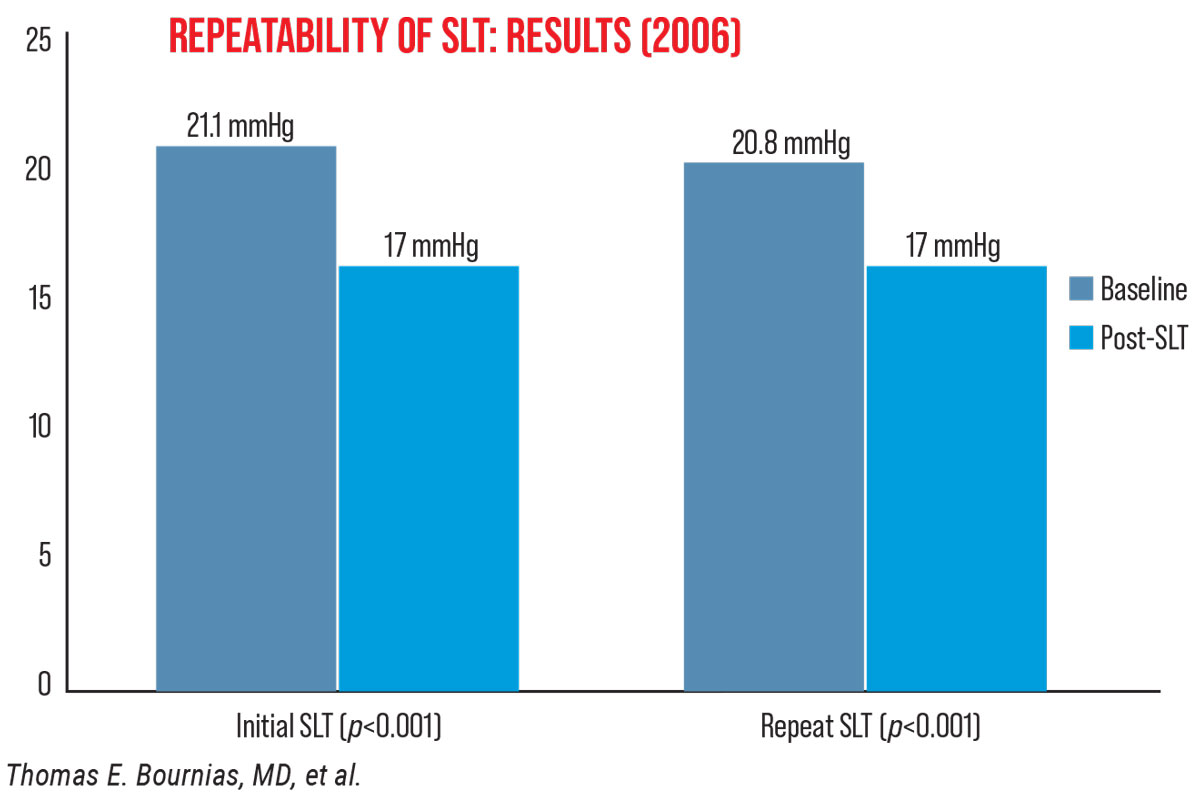

|

Dr. Bournias reports that his 2006 findings suggested SLT can be repeated up to three times. “Back then, people wondered if we could repeat SLT, since there are no thermal effects, like with ALT,” he explains. “My study included 52 eyes treated with 360-degree SLT who had initial treatment success for at least one year. I found that 90 percent (47 eyes) had a successful repeat response maintained for at least one year and about 60 to 70 percent had another [third] response (Figure 2).

“When patients stop responding to SLT, I usually switch to ALT,” he continues. “I’ve found those patients have a response. Likewise, those who don’t respond to ALT often respond to SLT. You can do these treatments in any order you want; however, I recommend trying SLT first because of its lack of coagulative effect.”

Dr. Realini is the chief investigator of the Clarifying the Optimal Application of SLT Therapy (COAST) Trial. Among the research team are Dr. Gazzard and Mark Latina, MD, the inventor of SLT. COAST is slated to enroll more than 600 patients at up to 20 centers around the world to compare standard SLT treatment to low-energy SLT and explore a low-energy SLT retreatment paradigm akin to treat-and-extend for anti-VEGF.

Pearls for Success

Here are some strategies to keep in mind when performing SLT:

• Trial a prostaglandin to rule out inflammatory glaucoma. “If they don’t tolerate it, then it’s very likely their glaucoma is related to inflammation,” Dr. Asrani says. “I’m extremely hesitant to perform SLT on these patients because it can result in a massive fulminant rise of pressure. If they tolerate it, I offer them the choice of staying on the drug or doing SLT. Most choose SLT.”

• Get comfortable. Though the SLT process is a short one, if you or the patient aren’t comfortable, your accuracy with the laser may not be perfect, Dr. Asrani says.

• Identify angle structures correctly. “Learn compression gonioscopy to learn how to identify angle structures,” Dr. Asrani advises. “Many times what we think is the TM turns out to be a pigmented Schwalbe’s line or the ciliary body band. If you inadvertently laser the Schwalbe’s line, there won’t be too many downsides, except possible corneal edema, which is usually reversible. But if you inadvertently laser the ciliary body band, the eye will go into ciliary spasm and the refraction will change. The eye becomes very painful and severely inflamed, requiring prolonged steroid treatment. If you’re not able to identify the TM, you won’t know what you’re lasering.

“It’s important to target the TM correctly and perfectly, with an end-on spot,” he continues. “By that, I mean that the laser beam should be focused perpendicularly to the TM. Angulate the lens to achieve this.”

• Champagne bubbles. “Make sure you can see a bubble at least 50 percent of the time,” Dr. Gazzard says. “Some people are cautious and undertreat. Some look for streams of bubbles on every pulse, and that’s probably slight overtreatment.” Large bubbles are another sign of overtreatment, which may result in scarring, he adds.

• Titrate the laser power. “Do this as you work your way around the eye,” Dr. Gazzard says. “Angles vary tremendously in pigmentation, and what might be the right level of laser power for the heavily pigmented inferior angle may be insufficient for the superior angle.”

• Ask patients with deep-set eyes to lean back. “It’s not possible to use the upper lens mirror on these patients because you can’t angle it up anymore—the brow bone limits your access,” Dr. Asrani notes. “In those cases, I ask the patient to lean back from the slit lamp so I’m able to achieve laser treatment with the upper mirror area.”

Special Considerations

In patients with traumatic glaucoma you may only be able to laser the nonaffected areas of the TM. “Be sure to avoid lasering the area of the angle recession that indicates TM damage,” Dr. Asrani says.

“In phacomorphic angle closure patients, the lens is thick and occupies a lot of the anterior chamber and angle,” he continues. “These patients typically have raised pressures. In these cases, low-power SLT (about 0.6 mJ) with compression and angulation of the lens is recommended because these TM cells are quite pigmented and often in constant contact with the iris.

“Pigmentary glaucoma and pseudoexfoliation glaucoma also require lower-power SLT,” he adds. “These patients have a lot of pigment in the TM, which absorbs laser energy very quickly. Any higher powered SLT will result in a massive pressure spike.”

Drs. Realini, Bournias and Asrani have no related financial disclosures. Dr. Gazzard is a collaborator on the Belkin Laser Trial and receives financial support from Ellex and Lumenis.

1. Gazzard G, Konstantakopoulou E, Garway-Heath D, et al. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus eye drops for first-line treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma (LiGHT): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019;393:1505-16.

2. Spaeth GL, et al. The Glaucoma Laser Trial (GLT). Ophthalmic Surg 1985;16:4:227-8.

3. Francis BA. Laser trabeculoplasty questions in clinical practice. AAO.org. Accessed May 3, 2021.

4. Mathison ML, et al. Impact of intraoperative ocular lubricants on corneal debridement rate during vitreoretinal surgery. Clin Ophthalmol 2020;14:347-52.

5. Latina M, Tumbocon JAJ. Selective laser trabeculoplasty: A new treatment option for open angle glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2002;13:2:94-6.

6. Bournias TE, et al. Racial variation in outcomes of argon laser trabeculoplasty. Ophthalmol 1997;104(suppl):173.