In recent years, the origins, diagnosis and identification of dry eye have been the focus of much research. There have also been leaps forward in dry-eye management with the addition of the over-the-counter drop Systane (Alcon), the arrival of prescription Restasis (Allergan) and the possibility of the eventual introduction of agents such as Inspire's P2Y2. To fully recognize the impact these new therapies will have or are already having, however, it's important to realize how many people are affected by dry eye, whether in a severe form or as a milder condition that becomes bothersome in certain adverse environments. Thus, epidemiological studies of dry eye have come to the forefront in recent years. This month's article will discuss the design and findings of some of these epidemiological studies of dry eye.

A Dry-Eye Review

Dry eye is a chronic, multifactorial condition characterized by disturbances in the tear film and the ocular surface. It can be caused by deficiency of any one or more of the tear film components, or can be a component of systemic diseases, including Sjögren's syndrome, lupus and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Additionally, factors such as contact-lens wear and adverse environmental exposures such as arid environments, windy conditions or visual tasking can exacerbate the symptoms of dry eye. Since we're all exposed to such adverse conditions, dry eye affects nearly everyone at one time or another.

To date, there have been several major studies that have examined dry eye's distribution, determinants, and occurrence rate in human populations. Here is a look at their findings.

Women's Health Study1

The WHS was a large-scale, well-conducted study that consisted of 39,876 female health professionals aged 45 to 84 who were enrolled in a randomized control trial to assess the effects of aspirin and vitamin E on the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. A four-year follow-up questionnaire contained questions relating to the clinical diagnosis of dry eye and symptoms of ocular dryness and irritation.

For the purposes of the analysis, those who had a clinical diagnosis of dry eye or experienced ocular dryness and irritation constantly or often were classified as having dry eye. In the study, the prevalence of dry eye after four years of follow-up was 6.7 percent. Prevalence is a common epidemiologic measure of disease frequency and refers to the total number of cases existing in a population at a specific point in time. Note that prevalence is commonly confused with incidence, which is the number of newly diagnosed cases of disease that develop over a specific time period.

| Summary of Epidemiologic Studies of Dry Eye | ||||||

| Study Name | Study Population | Age | Study Design | Diagnostic Criteria | Prevalence (%) | Associations |

| Canadian Dry Eye Epidemiology Study |

13,517 subjects attending optometry clinics in Canada | <10 to >/= 80 years | cross-sectional (clinic based) |

Affirmative response to the question: "Do you have symptoms of dry eye?" |

28.7 | 1) female gender 2) 21-30 and >70 years age groups 3) contact-lens wear 4) history of allergy, dry mouth, or lid symptoms |

| Salisbury Eye Evaluation Project | 2,482 residents of Salisbury, Md. | 65-84 years | cross-sectional (population based) |

Report of >/= 1 dry eye symptom often or all of the time based on a standardized questionnaire | 14.6 | None |

| Melbourne Visual Impairment Project | 926 subjects in Australia | 40-97 years | cross-sectional (population based) |

>/= 2 signs of dry eye | 7.4 | 1) female gender 2) age >80 3) history of arthritis |

| Beaver Dam Eye Study | 3,703 subjects from Beaver Dam, Wis. |

48-91 years | cross-sectional (population based) |

self-reported history of dry eye | 14.4 | 1) female gender 2) age >70 3) current smoking 4) history of arthritis |

| Women's Health Study | 38,124 female health professionals | 49-89 years | cross-sectional (population based) |

self-report of clinical diagnosis or severe symptoms (dryness and irritation constantly or often) | 6.7 | 1) age >75 2) HRT users 3) Hispanic or Asian race |

In the WHS, Asian and Hispanic women were more likely to have dry eye than Caucasians. Older women were more likely to have dry eye. The prevalence was 5.7 percent in women under age 50 compared to 9.8 percent in those at least 75-years-old. The overall age-adjusted prevalence of dry eye was 7.8 percent. Research has also suggested that women who use hormone replacement therapy, especially estrogen, are at increased risk for dry eye.2

Compared to non-HRT users, estrogen users had 69 percent greater odds of having dry eye, and users of estrogen plus progesterone/progestin had 29 percent greater odds.2 For every three-year increase in the duration of HRT use, there was a 15-percent increase in the risk of dry eyee2

The Beaver Dam Eye Study

The BDES was a population-based cohort that consisted of 3,722 residents of Beaver Dam, Wis.3 Subjects were aged 48 to 91 years and were primarily Caucasian. The presence of dry eye was self-reported on a five-year follow-up questionnaire, and its prevalence was 14.4 percent. Dry eye was more common in women and in older age groups. The age-adjusted prevalence was 11.4 percent in men and 16.7 percent in women. Other factors associated with dry eye included smoking and a history of arthritis. Caffeine use was found to be protective in the subjects.

The Salisbury Eye Evaluation

The SEE was a population-based study aimed at investigating risk factors for eye disease and the impact of eye disease on older people.4 The study population consisted of 2,520 volunteers, aged 65 to 84, living in Salisbury, Md. Researchers assessed dry-eye symptoms using a six-item questionnaire, and subjects underwent Schirmer's and rose bengal tests.

The definition of dry eye was primarily based on the questionnaire. Subjects who reported at least one symptom often or all of the time as well as those who reported at least one and had abnormal test results (Schirmer's score 5 mm, rose bengal score Ž 5) were defined as having dry eye. Those who had abnormal tests results but reported no symptoms were not considered to have dry eye. The prevalence of dry eye based on subjects reporting symptoms was 14.6 percent. The prevalence of dry eye was 2.2 percent, based on those who were symptomatic and had a low Schirmer's score, and was 2 percent for those who had symptoms and an elevated rose bengal score. The study didn't report a significant effect of age, race or gender.

The Melbourne VIP

The Melbourne Visual Impairment Project was a population-based study of residents from Melbourne, Australia designed to study age-related eye disease.5 The study population consisted of 926 residents aged 40 to 97. Researchers assessed dry eye with a questionnaire, Schirmer's test, tear-film breakup time, rose bengal staining and corneal staining. The prevalence of dry eye varied with each method of assessment: 10.8 percent (rose bengal > 3), 16.3 percent (Schirmer's test < 8), 8.6 percent (tear-film breakup < 8), 1.5 percent (fluorescein staining > 1/3), 7.4 percent (two or more signs) and 5.5 percent (report of any severe sign not attributed to hay fever). Females were more likely to report symptoms but not have signs of dry eye. Those in older age groups and those who reported a history of arthritis were more likely to have two or more signs.

The Canadian Experience

The Canadian Dry Eye Epidemiology Study was designed specifically to assess the prevalence of dry eye in Canada.6,7 In the study, 30 copies of a questionnaire were mailed to all of the optometry clinics in Canada. Of the 86,160 questionnaires initially mailed out, 13,517 (15.7 percent) were returned. The subjects' ages ranged from younger than 10 to older than 80. A subject was considered to have dry eye if he answered yes to the following question: "Do you have symptoms of dry eye?"

Based on the questionnaire, 28.7 percent reported that they had dry-eye symptoms. Of these subjects, 90 percent reported having mild symptoms, 7.6 percent had moderate symptoms and 1.6 percent had severe symptoms. Certain populations had a higher prevalence of dry eye: females; subjects aged 21 to 30 or older than 70; contact-lens wearers; and those with a history of dry mouth, allergy or lid symptoms.

Strengths and Weaknesses

The research suggests that the prevalence of dry eye ranges between 5 and 28 percent. Several factors could cause this variation. The lack of a well-defined method of clinical diagnosis presents a major challenge to the study of the epidemiology of dry eye. All of the studies discussed here used a questionnaire to assess dry-eye symptoms. Some were supplemented by objective tests such as Schirmer's and rose bengal staining but the concordance between abnormal test results and the report of dry-eye symptoms appeared to be low. The CANDEES used the least restrictive definition of dry eye and reported the highest prevalence (28.7 percent).

Reliance on the self-reporting of symptoms on questionnaires can be problematic. The questionnaires are subjective, and it's unclear how many symptoms are necessary, or with what frequency a person must exhibit symptoms, to be correctly diagnosed with dry eye. The lack of a uniform method of assessing dry-eye syndrome makes comparing the various studies difficult. Ideally, assessment of dry eye should be done using an objective test. However, until more research is done on the sensitivity and specificity of dry-eye tests, questionnaires may be the only feasible option.

In addition to the lack of a well-defined diagnosis of dry eye, there are other factors that could cause variation in the prevalence estimates.

First, dry eye has a multifactorial etiology, which suggests that there may be several subtypes of dry eye to consider, each with its own set of risk factors. All of the studies considered dry eye as a single condition.

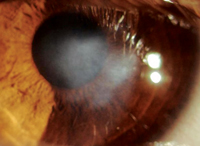

Additionally, dry eye can produce signs and symptoms that are easily confused with other conditions, such as ocular allergy, which can make diagnosis difficult. Upon closer questioning and examination, you can distinguish between the two: recall that itching typically indicates allergy, while burning or grittiness means dry eye. A detailed history is essential, and know that patients may often group all ocular complaints as "itching."

For example, if a patient reports itching, ask him if he feels the desire to rub the eye, indicating true itching and the presence of allergy. On the other hand, the person may feel irritation, dryness, burning or stinging in the eye, which is not a real itch but instead is more indicative of dry eye.

Tools such as tear-film breakup time and fluorescein or lissamine green staining can reveal the telltale symptoms of dry eye (Welch D, ARVO Abstract #2485, 2003), while the presence of redness, lid swelling and/or chemosis can support an allergy diagnosis.

An important factor impacting both allergy and dry eye is the use of over-the-counter systemic antihistamines. These can have a drying effect on the eyes, so, if patients are using these on their own for allergy, they may actually be exacerbating their dry eye (Gupta G, ARVO Abstract #70, 2002).8 This heightened dryness may then increase the intensity of any ocular allergic reaction since airborne pollens cannot be as easily washed or diluted from a dry eye.

Also, factors specific to each individual study could account for the variation in prevalence estimates. Each of the studies had a different age structure, which could have affected the prevalence number. Another difference between the studies was the source of the subjects. All of the studies were population-based except CANDEES, which drew its subjects from a clinic population. A population-based study makes inferences based on a sample of people from the general population, which can result in a more accurate estimate of disease prevalence. CANDEES reported the highest prevalence, but this isn't surprising given that subjects from clinics tend to be sicker than those from the general population.

One of the goals of epidemiologic studies is to identify high-risk populations that can be targeted for treatment. Based on the described studies, it appears that women, HRT users, the elderly, non-Caucasians, smokers, contact-lens wearers and those with a history of arthritis, allergy or dry mouth are at increased risk for dry eye. Clinicians should make an effort to screen these populations for dry eye and make them aware of the treatment options.

However, while our dry-eye screening should be heightened in these populations, all demographic groups can benefit from screening. The majority of people who walk into their ophthalmologist's or optometrist's office suffer from some degree of dry eye but may not mention it, or it may not be their primary reason for visiting the office. The key is to realize that such a large proportion of our patient population is experiencing these forms of discomfort due to dryness, though they may not recognize the cause or the availability of pharmaceutical agents that can provide relief.

Historically, artificial tears such as the Refresh product line (Allergan) and Genteal's tears (Novartis), have found broad acceptance in the market. These have since been joined by some newer options including long-lasting over-the-counter agents such as Systane, which has an in situ gelling property. Such an eyedrop can be the appropriate option for those with mild, moderate or intermittent symptoms. If taken on a regular schedule, such eyedrops can help prevent dry eye from becoming bothersome. A prescription agent such as the currently available Restasis, or future therapies such as P2Y2, may be the answer for some cases of dry eye.

Dr. Abelson, an associate clinical professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School and senior clinical scientist at Schepens Eye Research Institute, consults in ophthalmic pharmaceuticals. Ms. Rosner is a research associate at Ophthalmic Research Associates in North Andover.

1. Schaumberg DA et al. Prevalence of dry eye syndrome among US women. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;136:318-26.

2. Schaumberg DA et al. Hormone replacement therapy and dry eye syndrome. JAMA. 2001;286:2114-2119.

3. Moss SE et al. Prevalence and risk factors for dry eye syndrome. Archives of Ophthalmol 2000;118:9:1264-8.

4. Schein OD et al. Prevalence of dry eye among the elderly. Am J Ophthalmol 1997;124:723-8.

5. McCarty CA et al. The epidemiology of dry eye in Melbourne, Australia. Ophthalmology 1998;105:1114-9.

6. Caffery BE et al. The Canadian dry eye epidemiology study. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;438:805-6.

7. Doughty MJ et al. A patient questionnaire approach to estimating the prevalence of dry eye symptoms in patients presenting to optometric practices across Canada. Optometry and Vision Science 1997;74:9:624-31.

8. Welch D et al. Ocular drying associated with oral antihistamines (loratadine) in the normal population – an evaluation of exaggerated dose effect. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;506(Pt B):1051-5.