LASIK is still the leader of the refractive surgery pack. But even with steadily improving technology, missed targets and unhappy patients ocassionally turn up. Like LASIK itself, ideas about how to manage this continue to evolve.

John A. Vukich, MD, assistant clinical professor at the

Here, Dr. Vukich and three other surgeons share their thoughts on these trends and other issues surrounding LASIK enhancement, including when to use wavefront-guided enhancements.

What's Not Right?

Given that most outcomes today are very close to the intended result, a number of factors impact surgeons' decisions about whether to enhance, including the patient's attitude, the amount of enhancement being requested and the reason the outcome wasn't on target—if that was the case. William J. Fishkind, MD, co-director of

Obviously, whether to make a small enhancement also depends on the reason vision is not what the patient expected. "Probably the most common cause for complaint in a 20/20 post-LASIK patient is a mismatch between expectations and results, centered on the patient's understanding of presbyopia—despite our best efforts to explain this preoperatively," notes Dr. Vukich. "A few patients just don't seem to grasp that emmetropia combined with presbyopia may mean losing some of their near acuity. If that happens, we try to talk them through it. If the patient is adamant, we can enhance to reinstate some myopia, essentially creating mini-monovision. But we try to avoid that."

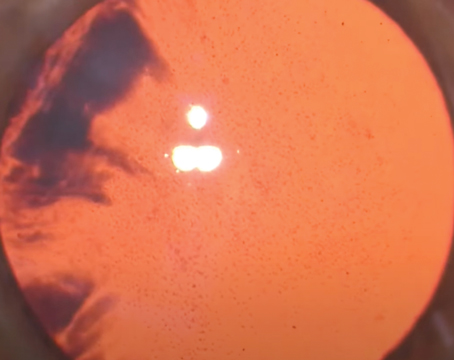

When the residual error is significant, these surgeons agree that determining the reason is paramount. "Especially in older patients, if they come back a few years later saying their nearsightedness has returned, you have to check them for cataract," notes Dr. Fishkind. "If a cataract is causing the problem, you don't want to use the laser. The problem will just come back again and you'll take more tissue. Also, you have to look for ectasia if the patient has become more myopic, regardless of age."

"I do a pretty extensive evaluation on these patients," says Daniel S. Durrie, MD, owner of Durrie Vision, in Overland Park, Kan. "I check topography for signs of keratoconus or other concerns; I do a wavefront scan to see whether the patient has higher-order aberrations; I do a dilated exam and check the lens for mild nuclear sclerosis if the patient is in his 40s or older. Assuming that blepharitis and dry eye are corrected, the eye is otherwise healthy and there are no other contraindications, I put the patient in the phoropter. If changing the focus a little causes a noticeable improvment, I'll do an enhancement."

"If it's my own patient, I always look at the original file and review the preop measurements to make sure there was no preexisting keratoconus," says Marguerite McDonald, MD, FACS, who practices at Ophthalmic Consultants of Long Island in New York and is clinical professor of ophthalmology at NYU School of Medicine. "I look at the printout from the laser and make sure it was programmed properly. If everything checks out, then it's okay to proceed.

"If the patient received LASIK from a surgeon other than myself, I won't operate unless I see the complete preop workup from the first surgeon," she notes. "I watch out for what I call 'second-surgeon syndrome.' Occasionally somebody will come to you for an enhancement, angry because their first surgeon missed the target by a wide margin.

Maybe they started out at -5 D and ended up at -1.5 D. They don't want to go back to the first surgeon, even if the enhancement would be free.

"The issue here is that nobody misses the target by that much unless there's underlying pathology," she says. "So, you really have to see every last one of the preop measurements, especially corneal thickness and the color-coded contour map. It's entirely possible that the patient had preop keratoconus, or a variant of it, which can lead to a destabilized cornea and residual myopia. If you don't realize that the patient had preop keratoconus and you do the enhancement, now you're the one who completely destabilizes the cornea. The patient may go on to need a corneal transplant. You're the one the patient will sue, even though you didn't make the initial mistake."

Keeping the Patient Happy

Ultimately, surgeons agree that patient satisfaction is key. "The last thing you want to do is try to make vision better if the patient is happy," notes Dr. Vukich. "You never want to create a problem where one doesn't exist. On the other hand, if the patient is unhappy but the correction would be very small, I try to make the patient understand that perfection isn't always easy to achieve and the pursuit of perfection is accompanied by risks. Many problems can occur when we're chasing small residual corrections, such as epithelial ingrowth, overcorrection or exacerbation of dry eye. We don't want to create trouble for a marginal benefit."

"Lately, a couple of unhappy patients were referred to me from other parts of the country," says Dr. Durrie. "Both of them just needed a simple enhancement; one had a half diopter of astigmatism, the other a half diopter of myopia. Nothing else was wrong—except that the original doctor had tried to convince them they didn't need an enhancement. It was their problem, he told them. Both had called lawyers and gone onto the chat lines and become anti-LASIK.

"Both of them were very demanding patients, but very nice people," he adds. "They were relieved when they found out that all they needed was a retreatment. But when they first came in they were really angry and ready to sue. The point is that we have to pay attention to the needs of these patients. Otherwise it hurts the reputation of LASIK surgery worldwide."

However, Dr. Durrie acknowledges that there are times when saying no to an enhancement makes perfect sense. "There are several valid medical reasons for saying no," he notes. "But it can't be just 'I don't want to do that.' "

"Whenever the visual outcome isn't as good as it ought to be, you have to acknowledge it," adds Dr. Fishkind. "The patient knows he's not seeing as well in one eye. If you try to gloss over that, all you do is create a lack of trust—or in the worst case, an adversarial relationship."

The Great Debate: Surface or Flap?

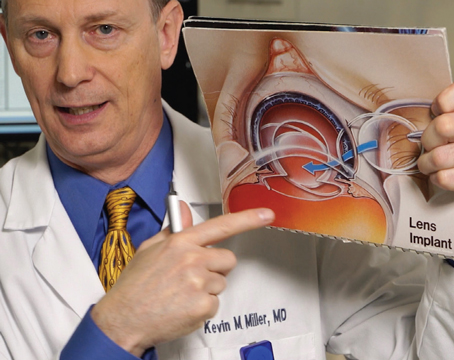

Probably the most debated issue in LASIK enhancements is whether or not to relift the flap to perform an enhancement. "Right now there are three camps," says Dr. Durrie.

"Some people lift every flap. Another camp never lifts the flap; they do PRK all the time.

But I think most surgeons are choosing based on the situation—they'll lift the flap if it's in the first year, especially if it's an IntraLase flap. Over the past three or four years data from papers has indicated that if you lift a flap more than three years after surgery, the incidence of epithelial ingrowth goes up significantly—from around 1 percent to almost 10 percent in some studies. On the other hand, avoiding PRK in first-year enhancements makes patients happier because these are the patients who missed their target; you want to give them quick visual recovery and low pain."

"The timing of the enhancement makes a difference," agrees Dr. Vukich. "I've noted that the flap changes in consistency over time; it doesn't lie back down the way it did when it was first cut. As a result, the risk of epithelial ingrowth eventually becomes a bigger problem than the potential for scarring or subepithelial haze that we associate with PRK. So, once I get past six months, I'll do everything I can to avoid lifting the flap; I'll use PRK instead."

Dr. McDonald prefers to do all enhancements on the surface. "Most enhancements are very small these days, so you won't be ablating deep enough to encounter the flap bed interface, which has been associated with epithelial ingrowth and increased chance of haze," she says. "That's true even with the modern thin flaps that LASIK surgeons now routinely create. In addition, doing the enhancement on the surface is fast and easy.

Patients have much less pain than they might following a primary ablation on the surface because most enhancements are done only three or four months after the primary surgery so a lot of the nerves cut during the creation of the LASIK flap have not reconnected yet. And patients heal quickly after the enhancement."

Dr. McDonald notes that not lifting the flap avoids any problem with epithelial ingrowth.

"When you first create a LASIK flap, you make a nice, sharp cut through the epithelium," she points out. "In contrast, when you lift a flap, you tear the epithelium. Little bits of it are lying around; they can then flip under the flap and easily end up at the interface and grow."

Dr. Fishkind says he tends to re-treat using whatever procedure was used for the primary surgery. "If it was a LASEK, I'll do a LASEK enhancement," he says. "If it was a LASIK, I usually lift the flap and do a LASIK enhancement. I'll do a surface enhancement when appropriate—when the cornea is thin, when there's terrible dry eye, or when the treatment is enough that I'm concerned that haze might be an issue. But in most cases, if the eye only needs a very small post-LASIK enhancement, my feeling is that it's better to lift the flap. I've had patients who had LASIK a couple of years earlier, and I've done them as LASEK; I've found that it's very hard to keep the flaps from getting distorted.

Besides, any time you work under a flap, the return of vision is much faster. The amount of handholding, temporizing and supporting goes down significantly."

Managing Epithelial Ingrowth

Epithelial ingrowth is something many surgeons encounter after enhancements made under the flap. "If an epithelial ingrowth is small and not central or affecting vision, you leave it alone," says Dr. Fishkind. "Many times they resolve by themselves. If it gets worse over the course of a month or two, then you have to lift the flap and scrape it off; I use a #69 beaver blade. I put a little alcohol on it to kill the cells and put the flap back. If the ingrowth is central, it will cause significant distortion in the visual axis, so you have to act quickly."

Dr. Durrie notes that there are many unanswered questions regarding epithelial ingrowth, and he's hoping to resolve some of them. "One problem is that epithelial ingrowth has never been classified, so it's impossible to grade accurately," he observes. "Some surgeons who say they never encounter epithelial ingrowth are really just saying they don't get any bad ones; they're not counting small ingrowths that aren't clinically significant. We need to define some parameters so we're all on the same page."

Dr. Durrie is currently conducting a prospective study that may shed some light on exactly what causes epithelial ingrowth when a LASIK flap is lifted. "We're looking at what's going on in the OR and around the patients," he explains. "One part of the study involves creating a diagram in the OR showing exactly where we touch the cornea with the instrument, where we enter the flap, any epithelial defects or tags, and so forth. Then, at the one-month visit we're doing a drawing/diagram of the location of any ingrowths, even small ones that are not clinically significant.

"Finally, we're doing a statistical analysis to see if areas that have ingrowth were either touched by the instrument or had an epithelial defect," he says. "This should tell us whether the ingrowth is associated with where we touch the flap, whether the type of instrument matters, and so forth. The study is ongoing, but my impression is that in eyes that have no epithelial defects, and those in which you're able to lift the flap with very few manipulations, you get the least ingrowth.

"The other thing that's coming out of the study," he continues, "is the importance of controlling blepharitis. When you lift the flap, even mild uncontrolled blepharitis seems to make the epithelium more active and likely to end up under the flap. So my number one suggestion is to control blepharitis really well before you do a lift-flap enhancement."

The Dry-Eye Factor

As noted by Dr. Vukich, one important trend in LASIK enhancement has been the recognition that dry eye can have a profound influence on how the surgery comes out—and whether or not an enhancement is even necessary. "I find that a significant number of patients who are undercorrected in sphere or cylinder—mainly myopes—have blepharitis or dry eye," says Dr. Durrie. "So my first approach is to treat that aggressively with lid hygiene, omega-3 oils, even doxycycline as needed."

Dr. McDonald agrees, noting that outside patients who come in a little bit myopic and unhappy with the surgeon who did the primary LASIK often simply have an untreated case of dry eye. "In some cases I've put those patients on Restasis, usually followed by punctal plugs," she says. "I've seen people who were headed for an enhancement go all the way back to

This has been Dr. Vukich's experience as well. "In many cases, the enhancement can be done pharmacologically, just with surface preparation and re-establishing a good tear film," he says. "Even if a patient only has a slight amount of dry eye, re-establishing a healthy tear film will inevitably create a better quality of vision. I think that's part of the reason our enhancement rate has dropped; tear therapy not only makes patients more comfortable, it improves the quality of their vision and avoids further surgery.

"We use this approach before the primary surgery if a patient admits to any dry-eye discomfort at all, even if he doesn't show signs of staining, because a patient's perception will often precede the signs that we can see at examination," he adds. "Plus, we know that LASIK will diminish the feedback loop for tear production and reduce corneal sensitivity for a period of a few months, so doing this preop makes sense. But we also use this approach in situations where we're looking at a small residual correction, or for patients who feel their postop vision isn't quite right. A lot of the time they'll get better from that alone."

Wavefront Enhancement?

Although wavefront-guided correction has become commonplace, surgeons disagree about whether it should always be used for enhancements. "We preferentially use wavefront-guided treatments with iris registration and pupil centroid adjustment, especially for enhancements," says Dr. Vukich. "We often find induced spherical aberration and coma in individuals who are seeking enhancement. The only cases in which we don't use wavefront are those rare individuals in whom we cannot capture a wavefront map because of pupil size or topography."

Dr. McDonald, who performs her enhancements on the surface, also reports that wavefront enhancements work great—and sees this as another reason to favor surface enhancement. "When you lift and replace the flap, you put it down in an ever-so-slightly different position, altering the wavefront map," she says. "There's really no way to avoid that, and it could affect the outcome. If you do surface ablation, you are truly treating what you measure." She adds that wavefront-guided enhancements also eliminate the possibility of an error when correction data are entered into the laser—something she once encountered in her own practice—since the data are captured and fed directly into the laser without human intervention.

Dr. Fishkind, who usually lifts the flap to enhance a LASIK treatment, has reservations about using wavefront when the original treatment was also wavefront. "I've found that if you do a wavefront enhancement on top of a wavefront procedure, you end up taking more tissue and getting less desirable outcomes," he says.

Dr. Durrie, who bases his decision about whether or not to enhance with wavefront on the extent of higher-order aberration he finds, agrees that it is possible that lifting the flap could affect the accuracy of a wavefront enhancement by shifting the wavefront map when the flap is laid back down. "That has not been my experience, but I appreciate the reasoning," he says. "In fact, I'm planning to conduct a randomized multicenter study on this, comparing patients who have the flap lifted with those who don't."

Outlook: Excellent

As long as LASIK remains popular, there will always be a few unhappy patients.

Hopefully, the number of these patients will continue to drop as our knowledge increases and technology continues to improve. In the meantime, the vast majority of patients will experience dramatically improved vision and help to spread the good word.