Because the retina is an extension of the brain, it’s often possible to get an idea of what’s happening in the brain by examining the eye. Data from recent studies suggests that changes in the retina may be associated with the presence of Alzheimer’s disease, opening the door to the possibility of catching Alzheimer’s early and monitoring its progress.

Blood Flow & Retinal Thickness

One possible approach to detecting Alzheimer’s disease via an eye examination involves using laser Doppler blood flowmetry and/or optical coherence tomography to measure changes occurring in the retina. Gilbert T. Feke, PhD, currently senior research associate at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary in Boston, has been working on this possibility for several years. His work has revealed that individuals with Alzheimer’s disease have differences in retinal blood flow and nerve fiber layer thickness compared to normals, some of which are detectable with these technologies.

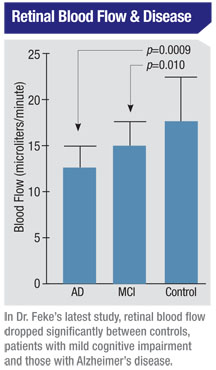

“In our initial study1 we found that patients with overt Alzheimer’s disease had retinal nerve cell loss and blood circulation abnormalities compared to control subjects,” he explains. “Retinal veins were thinner in patients with Alzheimer’s, and blood flow was slower. Our current study is designed to see if those abnormalities appear in the pre-Alzheimer’s condition known as mild cognitive impairment. So far we’ve looked at more than 50 subjects, and the study shows a clear progression in terms of reduced blood flow from controls to those with mild cognitive impairment to those with Alzheimer’s.”

Dr. Feke says the impact of the disease on nerve fiber layer thickness is more subtle. “We do see thinning in the Alzheimer’s group compared to the controls,” he says. “But we don’t see it happening at all in the mild cognitive impairment group, compared to controls. There’s been some question as to whether the loss of nerve cells precedes the blood flow decrease, or the other way around. There’s data in the literature that indicates that blood flow problems in the brain happen first, starting a cascade of damage, and our results seem to support that.”

Dr. Feke says the impact of the disease on nerve fiber layer thickness is more subtle. “We do see thinning in the Alzheimer’s group compared to the controls,” he says. “But we don’t see it happening at all in the mild cognitive impairment group, compared to controls. There’s been some question as to whether the loss of nerve cells precedes the blood flow decrease, or the other way around. There’s data in the literature that indicates that blood flow problems in the brain happen first, starting a cascade of damage, and our results seem to support that.”

Dr. Feke admits that retinal blood flow is not something clinicians ordinarily check. “However, clinicians can measure vessel diameters,” he points out. “Our research found that, on average, retinal veins are 135 µm in diameter when Alzheimer’s is present; 151 µm in mild cognitive impairment; and 158 µm in controls. Because of the relatively small number of subjects in our study, as well as the relatively large range of venous diameters in the eyes of control subjects, the difference between the mild cognitive impairment group and controls is not statistically significant. Interestingly, the difference in blood speed is significant —blood speed in controls is 33.5 mm/sec; in the mild cognitive impairment group it’s 27.3 mm/sec.”

Could these type of measurements serve as a means of early detection for Alzheimer’s? “If blood vessel diameters are normal, that might help to rule out Alzheimer’s,” says Dr. Feke. “But for now, I think the value of this work is more that it’s shedding light on mechanisms of damage.

“In the future, if we can measure these parameters in a very large number of subjects, we may be able to narrow down the range of what is healthy in terms of vessel diameters, as a function of age and other factors. Then it could conceivably be possible to detect early disease by measuring vessel diameters. A good approach would be to use a measurement of central retinal vein equivalent diameter for this purpose. That measurement can be made with currently available software using a retinal photograph.”

Dr. Feke is less hopeful about using current OCT technology for early detection. “Our data suggests that there isn’t much happening to nerve fiber layer thickness that’s detectable with OCT until overt Alzheimer’s shows up,” he says. “Also, other conditions could produce thinning of the nerve fiber layer, confounding the usefulness of this as a diagnostic approach. But with more research involving a larger number of subjects, and future generations of OCT technology, it could become possible to catch Alzheimer’s in its early stages.”

Drusen in the Periphery

A recent study conducted in London used the Optomap wide-field retinal imaging device (Optos) to capture images of the periphery of the retina in 102 subjects, of whom 56 were Alzheimer’s dementia patients; the remainder were age-matched controls. The study found a highly significant association between the presence of drusen in the retinal periphery and Alzheimer’s disease.

Tunde Peto, MD, PhD, head of the reading center in the Department of Research and Development at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London, and Imre Lengyel, PhD, from the Department of Ocular Biology and Therapeutics at the University College London Institute of Ophthalmology, were the principal researchers. (The study was funded by multiple sources, including an unrestricted grant from Optos, but Optos was not directly involved in the study.)

“Based on our previous studies on cadaveric eyes, we hypothesized that if deposit formation in the brain could be correlated with deposit formation in the eye, then an extensive deposit formation at the peripheral retina—greater than 70-degree eccentricity—might be a better indicator of disease process than looking at the central area of the retina,” explains Dr. Lengyel. “However, imaging the peripheral retina has only been possible since the introduction of Optos ultra-wide-field imaging.

“We first tested the use of the Optos scanning laser ophthalmoscope during the 12-year follow-up of the Reykjavik Eye Study, which demonstrated that imaging small deposits, like drusen, was feasible to a high level of sensitivity using this device,” he continues. “After successfully imaging an aged population, we teamed up with Dr. Craig Ritchie at the West Mental Health Trust in London to image patients with Alzheimer’s disease.”

Dr. Lengyel notes that imaging Alzheimer’s patients proved to be more challenging than imaging age-matched controls. “Nevertheless, laser technology allowed reasonable image quality even in individuals with lens and vitreous opacities,” he says. “We found that eyes with small, hard drusen on diagnosis were significantly more associated with Alzheimer’s than with control status. Other macular degeneration-like pathological signs did not differ between controls and cases.”

Dr. Lengyel notes that if drusen deposition in the eye is associated with deposit formation in the brain, then small, hard drusen might become an easily identifiable surrogate marker for detection of Alzheimer’s. Dr. Peto agrees. “The possibility of early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s through deposit formation in the eye using a noninvasive, fast and easily reproducible methodology provides a window of opportunity for earlier intervention—and monitoring of the success of an intervention,” he says.

“Furthermore, [this technology] has the potential to be used to monitor other deposit-forming diseases,” he continues. “Monitoring changes occurring in the periphery has already been shown to be very useful for finding peripheral melanoma, retinal detachments and leaky vessels, so the use of ultra-wide-angle imaging is now gaining popularity. In addition, the inclusion of autofluorescence in the Optomap will now allow the assessment of retinal pigment epithelial changes that might become an invaluable tool for monitoring metabolic problems and cell atrophy.”

Dr. Peto says the next step is to validate the findings of the pilot study in a larger population. “It’s also imperative to set up a prospective study using well-characterized patients, including subjects with mild cognitive impairment, to clarify the usability of these observations as a diagnostic tool,” he says. “Also, correlation between deposit formation in the brain and the eye needs to be investigated.” As for the longer term? “We don’t believe we have enough data to warrant routine use of this for Alzheimer’s diagnosis yet,” he says, “but we hope that will change in the future.”

1. Berisha F, Feke GT, Trempe CL et al. Retinal abnormalities in early Alzheimer’s disease. Invest Ophthlamol Vis Sci 2007; 48:2285-9.