Presentation and Initial Work-up

|

|

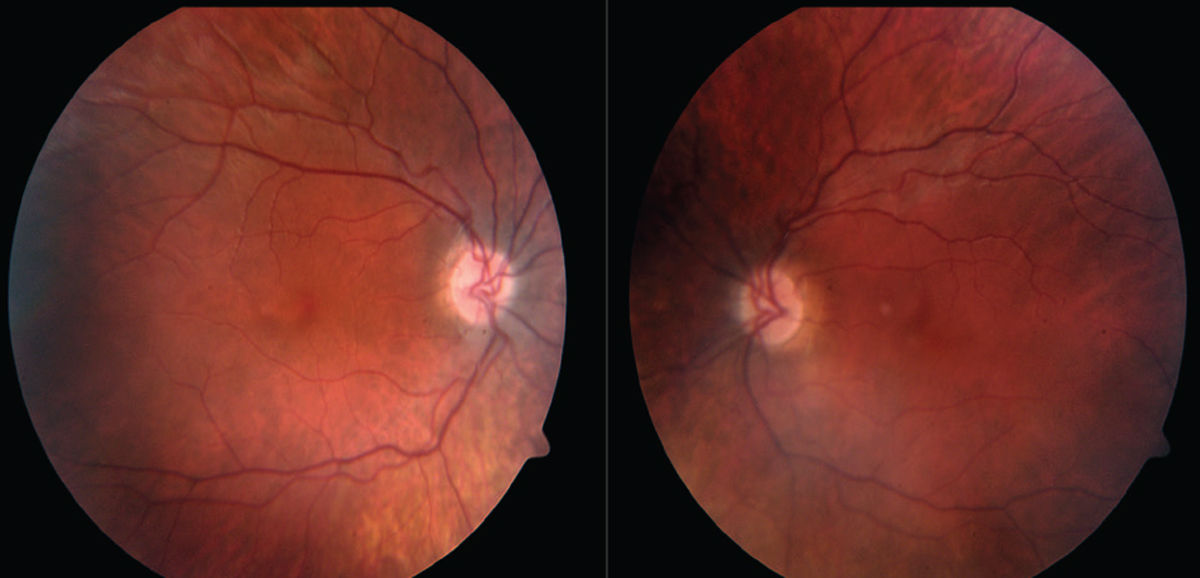

Figure 1. Fundus photo montage of the right eye revealed central atrophy of the macula, a blunted foveal reflex, and mottled depigmentation with mild vascular attenuation in the periphery. Fundus photo of the left eye appeared similar (not pictured). |

A 20-year-old male presented to the retina clinic with blurred vision in both eyes. He had been diagnosed with bilateral amblyopia by several eye-care providers during childhood who documented normal eye examination with reduced visual acuity recorded as 20/80 OU at age 3 and 20/50 OU at age 5.

Medical History

Past medical history was notable for delayed speech, delayed motor development and autism spectrum disorder as a child, and mild bilateral sensorineural hearing loss and hypertension during adolescence. Within six months of presentation, evaluation for extreme fatigue revealed anemia secondary to chronic renal failure. He had no surgical history. Family history was significant for hearing loss in his father and both grandfathers, and mild hearing loss in his mother. He denied alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use.

Exam

Best corrected visual acuity was 20/40 in the right eye and 20/30 in the left. Pupillary examination was normal. Confrontational visual fields and extraocular movements were full. Intraocular pressures were within normal limits OU.

Slit lamp biomicroscopic examination of the anterior segments was normal. Dilated fundus exam was notable for mild disc pallor, central atrophy of the macula, and a blunted foveal reflex OU (Figures 1 and 2).

|

| Figure 2. Fundus photos of the posterior pole show mild disc pallor and central atrophy of the macula. |

What is your diagnosis? What further work-up would you pursue? The diagnosis appears below.

Work-up, Diagnosis and Treatment

|

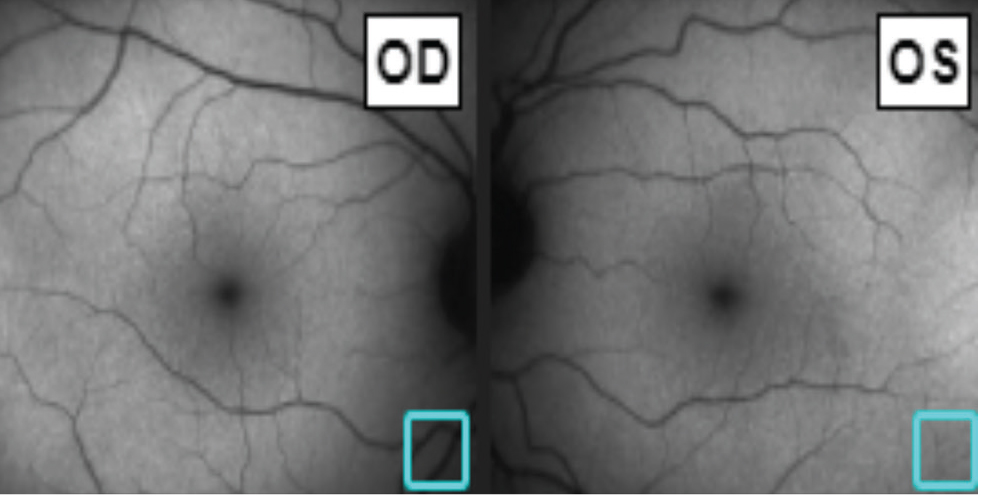

| Figure 3. Fundus autofluorescence was unremarkable. |

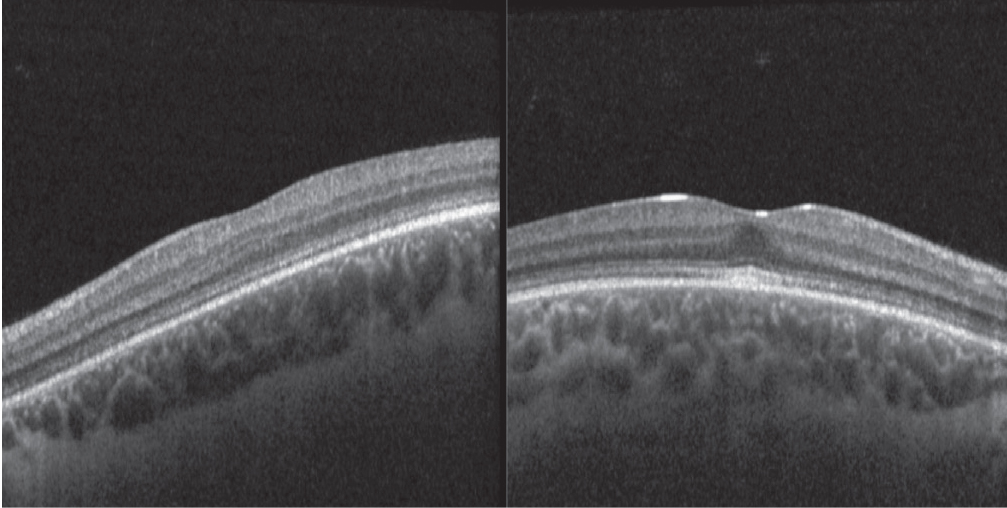

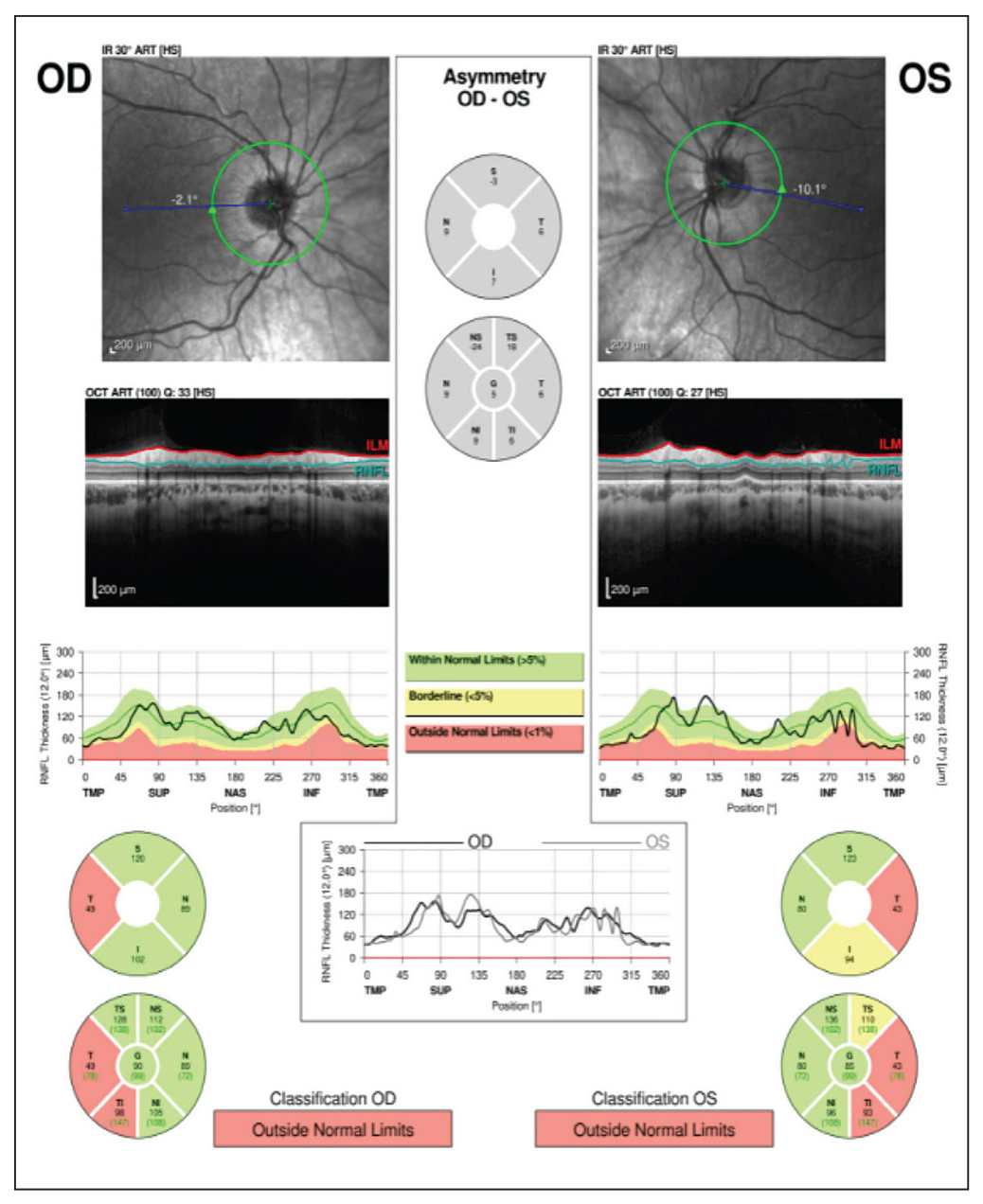

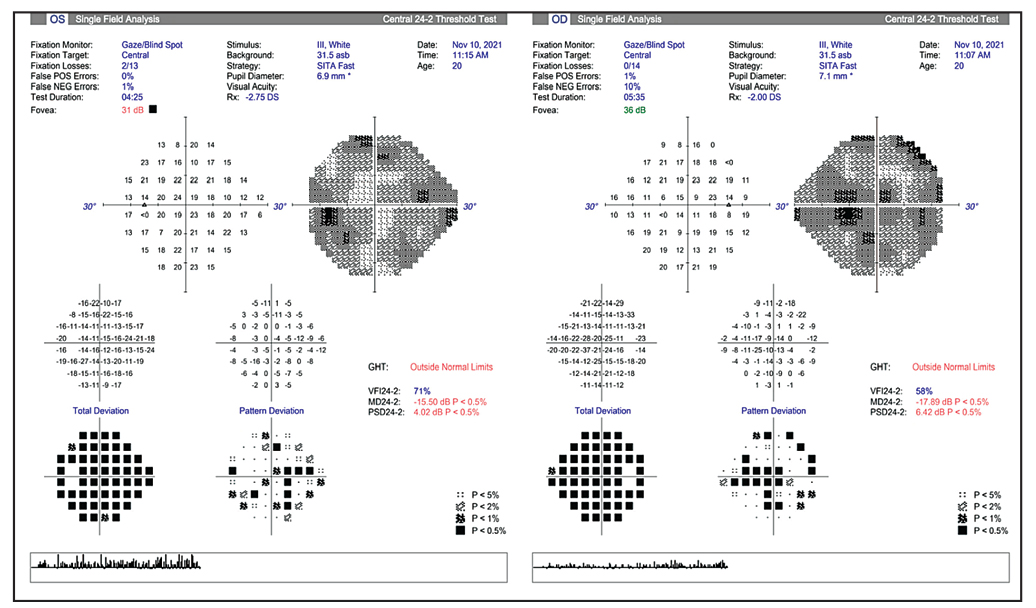

Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) was unremarkable (Figure 3). Macular optical coherence tomography revealed outer retinal atrophy with relative sparing of the fovea (Figure 4). OCT of the optic nerve revealed bilateral temporal retinal nerve fiber layer thinning (Figure 5). Humphrey visual field 24-2 testing demonstrated diffuse suppression with scattered paracentral defects bilaterally (Figure 6). Electroretinography photopic and scotopic waveforms and multifocal electroretinography wavelet amplitude throughout the macula were reduced to 25 percent of normal in both eyes.

|

| Figure 4. OCT demonstrating outer retinal atrophy with relative sparing of the fovea. |

Review of serology revealed serum creatinine had risen steadily from 1.2 to 3.4 mg/dL over the past three years. Renal function studies, including 24-hour urine albumin (49.8 mg/24 hr) and albumin/creatinine ratio (81 mg/g), were elevated. Renal ultrasound was remarkable for reduced kidney size.

Based on clinical history, examination, multi-modal imaging and lab work, an inherited retinitis pigmentosa syndrome was suspected. Whole genome exome sequencing revealed biallelic pathogenic variants of the NPHP1 gene which confirmed the diagnosis of Senior Loken Syndrome.

|

| Figure 5. OCT of the optic nerve demonstrating bilateral temporal retinal nerve fiber layer atrophy. |

The patient and his family attended genetic counseling, and the diagnosis was shared with the patient’s nephrologist. The patient is preparing for dialysis while awaiting renal transplantation. He is following with audiology and ophthalmology for periodic examinations.

Discussion

Senior Loken syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive disorder marked by retinal degeneration and renal failure characterized by inflammation and fibrosis, known as nephronophthisis.1 Its prevalence is approximately 1 in a million people worldwide.1 Senior Loken syndrome is categorized as a ciliopathy owing to malfunction of cilia, the microtubule-based organelles that extend from cell surfaces and facilitate molecular signaling.2 The NPHP genes encode cilia-associated proteins called nephrocystins, which are found in the cilium of photoreceptors and renal cells.3 These proteins are necessary for photoreceptor outer segment formation,4 and thus miscoding results in the diminished visual acuity in Senior Loken syndrome.

Patients commonly develop visual symptoms in the first decade of life, and may experience progressive visual impairment and nyctalopia. The majority have a mild retinal phenotype predominantly affecting cones with relative sparing of the fovea, although the retinal presentation can range from a severe Leber’s congenital amaurosis to typical retinitis pigmentosa.4 There may be no obvious structural changes on physical exam, as in this patient’s childhood eye examinations. However, OCT can reveal reduced reflectivity, a granular appearance of the ellipsoid zone, loss of the interdigitation zone and mild outer retinal thinning.5

|

| Figure 6. HVF 24-2 showing diffuse reduction with scattered paracentral defects. |

Renal symptoms typically occur before visual symptoms in Senior Loken syndrome; renal function becomes impaired due to inflammation and fibrosis as a result of damage to the ciliated epithelial cells of the nephron and collecting duct.6 Renal ultrasound may reveal interstitial fibrosis and cortico-medullary cysts.7 Polyuria, polydipsia and fatigue are common initial symptoms, followed later by anemia and uremia.8

Senior Loken syndrome may be differentiated clinically from other ciliopathies including Alport Syndrome, Joubert Syndrome and Bardet-Biedl Syndrome. Alport syndrome features hematuria with progressive nephropathy in addition to sensorineural hearing loss, anterior lenticonus and abnormal retinal pigmentation.9 In Joubert Syndrome, cerebellar vermis and brainstem hypoplasia, infantile hypotonia, and oculomotor apraxia accompany nephronophtisis and retinal dystrophy.10 Bardet-Biedl syndrome is typified by post-axial polydactyly, truncal obesity, renal abnormalities and retinitis pigmentosa.11 Dozens of other ciliopathies exist, with wide-ranging systemic effects, including cardiac defects, cognitive impairment, hydrocephalus, craniofacial defects, skeletal abnormalities, polydactyly, liver and pancreatic cysts, and genital defects.12

Treatment for Senior Loken syndrome is primarily supportive. Patients should undergo periodic ophthalmologic assessment with low-vision services as necessary. Although there’s no specific treatment for nephronophthisis, ongoing management by nephrology is critical for managing secondary complications of renal failure and planning dialysis and or transplant which are often required by mid to late adolescence. Genetic counseling should be offered to the patient and family. Referral to ENT is indicated to identify and remediate hearing loss. Furthermore, referral to psychology for establishment and management of ongoing individualized education plans based on visual and hearing limitations as early as possible is important to optimize classroom education and can be life-changing.

In summary, we describe a patient with clinical, examination and multi-modal testing findings of retinitis pigmentosa in addition to systemic features of chronic kidney disease and hearing loss, which raised suspicion for a ciliopathy. Genetic testing confirmed the diagnosis of Senior Loken syndrome.

1. Senior-Løken syndrome. MedlinePlus. Accessed June 1, 2012. medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/senior-loken-syndrome/.

2. Goetz SC, Anderson KV. The primary cilium: A signaling centre during vertebrate development. Nat Rev Genet 2010;11:5:331-44.

3. Hildebrandt F, Otto E. Molecular genetics of nephronophthisis and medullary cystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000;11:9:1753-1761.

4. Jiang ST, Chiou YY, Wang E, Chien YL, Ho HH, Tsai FJ, Lin CY, Tsai SP, Li H. Essential role of nephrocystin in photoreceptor intraflagellar transport in mouse. Human Molecular Genetics 2009;18:9:1566–1577.

5. Birtel J, Spital G, Book M, Habbig S, Bäumner S, Riehmer, Beck BB, Rosenkranz D, Bolz HJ, Dahmer-Heath M, Herrmann P, König J, Issa PC. NPHP1 gene-associated nephronophthisis is associated with an occult retinopathy. Kidney International 2021;100:5:1092-1100.

6. Deane JA, Verghese E, Martelotto LG, Cain JE, Galtseva A, Rosenblum ND, Watkins DN, Ricardo SD. Visualizing renal primary cilia. Nephrology (Carlton) 2013;18:3:161-8.

7. Aguilera A, Rivera M, Gallego N, Nogueira J, Ortuno J. Sonographic appearance of the juvenile nephronophthisis-cystic renal medulla complex. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1997;12:625–26.

8. Amarpreet K, et al. Senior Loken Syndrome. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research 2016;10:11:SD03-SD04.

9. Laurence H, Knebelmann B, Gubler MC. Alport Syndrome: Clinical Features. In: Turner NN, Lameire N, Goldsmith DJ, Winearls CG, Himmelfarb J, Remuzzi G, eds. Oxford Textbook of Clinical Nephrology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

10. Joubert M, Eisenring JJ, Robb JP, Andermann F. Familial agenesis of the cerebellar vermis. A syndrome of episodic hyperpnea, abnormal eye movements, ataxia and retardation. Neurology 1969;19:813–25.

11. Forsythe E, Beales PL. Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 2013;21:1:8-13.

12. Lee JE, Gleeson JG. Emerging genetics of the ciliopathies. Genome Med 2011;3:9:59.