The idea of a sustained-release implant that can deliver a drug slowly and steadily without requiring any patient action is certainly not new. However, making it a reality in ophthalmology has been challenging; creating safe and effective devices and getting them approved has taken years.

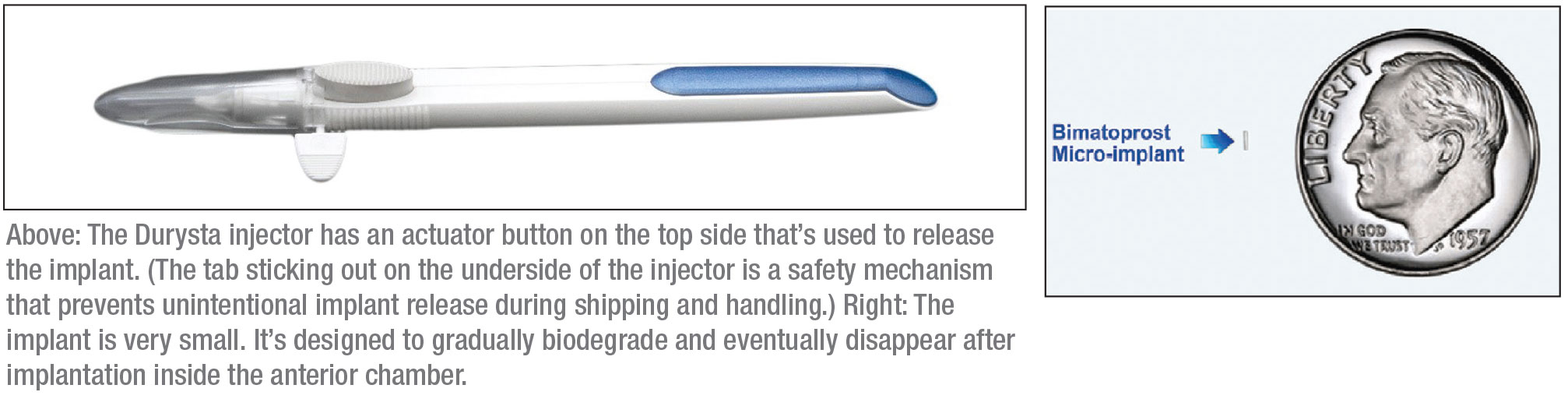

This March, doctors treating glaucoma finally got their first sustained-release option when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Allergan’s Durysta implant. The de-vice contains 10 µg of bimatoprost, a prostaglandin analog, which is slowly released over a period of 12 weeks after it’s injected into the anterior chamber. (Data from the clinical trials that led to approval suggest that its beneficial effects may last longer than that.) This implant may offer many patients a way to lower their intraocular pressure without having to use drops.

Here, doctors with experience using the implant during the clinical trials answer eight key questions about the new device and offer some thoughts about what may lie ahead for sustained-release treatments.

What Do the Studies Say?

E. Randy Craven, MD, an associate professor at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and former chief of glaucoma at King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, participated in a multicenter Phase I/II, prospective, controlled, 24-month, dose-ranging, paired-eye clinical trial of the bimatoprost implant (the APOLLO study), involving 75 eyes of adult patients with open-angle glaucoma.1 The study eye in each patient received an intracameral implant with either 6, 10, 15 or 20 µg of bimatoprost; the control eye received topical bimatoprost 0.03% drops. Rescue drops, or a single repeat administration of the implant, were permitted. The primary endpoint was IOP change from baseline.

Results included:

• At 24 months, mean IOP reduction from baseline was 7.5 mmHg for eyes with the 6-µg implant; 7.3 mmHg for eyes with the 10- and 15-µg implants; and 8.9 mmHg in eyes receiving the 20-µg implant. (IOP was reduced by 8.2 mmHg in the fellow eyes that received topical drops.)

• At six months, 68 percent of study eyes hadn’t been rescued or re-treated; at 12 months, 40 percent hadn’t been rescued or retreated; and at 24 months, 28 percent hadn’t been rescued or retreated.

• In terms of adverse events, those occurring in study eyes two days or less after the implantation were typically transient. After that point, the overall incidence was similar in study eyes and fellow eyes. However, the study eyes did show a lower incidence of some events typically associated with topical prostaglandin analogs. No in-cidences of endophthalmitis were encountered.

• If a second implantation was per-formed, the efficacy of the implant was similar to that of the first one.

• The implants gradually bio-degraded after implantation. By 12 months, the majority of implants received at the first visit had either totally biodegraded or were estimated to be ≤25 percent of their original size.

The implant’s efficacy was also compared to that of twice-daily topical timolol 0.5% drops in a pooled Phase III, 20-month-long, multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial (ARTEMIS) involving 1,122 patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. In both groups, the implant reduced IOP about 30 percent from a baseline mean IOP of 24.5 mmHg (lowering IOP 5 to 8 mmHg) over the 12-week period.

The device was well-tolerated in the majority of patients; however, immediate post-injection irritation was noted, with 27 percent of patients experiencing conjunctival hyperemia, and 5 to 10 percent experiencing foreign body sensation, eye pain, photophobia, conjunctival hemorrhage, dry eye, irritation and increased IOP. Later, some patients experienced corneal endothelial cell loss, blurred vision, iritis and/or headache.

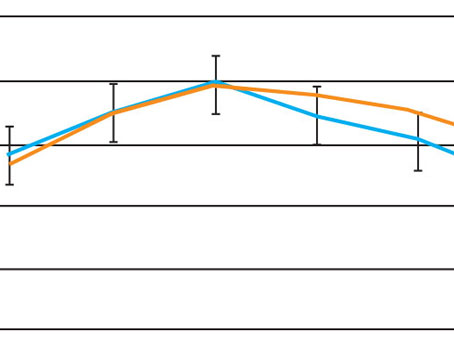

Felipe A. Medeiros, MD, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Ophthalmology, director of clinical research and vice chair for technology at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, also participated in the trials of the new sustained-release device. He says that a preliminary post-hoc analysis of the ARTEMIS trials suggests that the implant may preserve the visual field better than timolol. “We found that over the course of one year, eyes randomized to Durysta had a slower rate of change in standard perimetry mean deviation than eyes that were randomized to timolol,” he explains. “We’re now retrieving more extensive data so we can look at this in more detail, with a longer follow-up time.”

|

Who’s Eligible?

Dr. Craven points out that the patient must have open angles to be eligible for the implant. “You need room to place it,” he says. “Most primary open-angle glaucoma or exfoliative glaucoma patients would be good candidates. I probably wouldn’t put one into an eye with corneal dystrophy or iritis.

“As far as safety, when two or three implants were in the eye the FDA was concerned that some of the patients had lower endothelial cell counts than at baseline,” he continues. “However, I suspect the safety of the implant will improve as new versions are developed.”

In terms of what might disqualify patients from receiving the implant, Dr. Medeiros agrees that patients with a history of angle closure or corneal diseases such as corneal dystrophy, or with a low endothelial cell count, wouldn’t be eligible. “However, patients with these problems are relatively uncommon,” he notes.

How Will It Be Used in Practice?

In terms of use in the clinic, Dr. Craven notes a number of considerations. “Clinics may find different ways to offer this option to patients,” he says. “Some doctors may simply put it in whenever a patient requests it. Others, like me, may schedule a given day as an implant clinic and do multiple patients in a row. One reason for setting it up this way is that it’s easier to make sure we have insurance approval, and that the specialty pharmacy has sent the implant for each patient. The other reason is that I’ll most likely be using our minor procedure room to do this, and I’ve found that mobilizing the clinic team is easier if you do several patients in a row.”

“Patient prep would be similar to that done for other intracameral or intraocular injections performed in the office,” says Dr. Medeiros. “The procedure itself can be done at the slit lamp and should only take a few minutes.

Dr. Craven agrees. “We’ll use topi-cal anesthesia and topical Betadine,” he explains. “The implant injector has a 28-gauge, sharp, fine needle. It takes a few minutes to do the whole procedure, and we avoid talking, and/or wear a mask, during the injection. The procedure can be done at the slit-lamp or in a minor room, or even in the OR if you want.”

Dr. Medeiros notes that there are no clear guidelines regarding follow-up. “In general, I’d say patients could be seen one week later to make sure there are no adverse events,” he says. “Some doctors might prefer to have a one-day evaluation as well. Long-term follow-up will depend on the individual patient, but in general, glaucoma patients are monitored every four to six months, and I’d expect a similar schedule with these patients.”

“I’d probably follow up within a week and then every three to four months after that,” says Dr. Craven. “Based on the Phase I trial data, I think many patients will get more than six months of pressure control from the device. Some will get years of control.”

What Do Patients Think?

Dr. Craven believes it’s too early to draw conclusions about how patients will react to having the implant, but says he was seeing signs of interest in the clinic before the pandemic struck. “Some patients brought in Web clippings and asked about it,” he recalls.

“During the study, most patients were in favor of going with the implant rather than drops,” he continues. “About 80 percent of patients in the Phase I study reported being happy to not be using drops. This probably wasn’t 100 percent because they still had to use drops in the non-implant eye.

|

“The implantation itself is minimally uncomfortable, with no pain, and no patients reported feeling it once it was in place,” he adds. “None of the patients in the Phase I study requested removal. In the Phase III trial, a few were removed after several implants had been placed, but that was because the investigator was concerned about multiple implants irritating the cornea.”

“Patients reacted very well to receiving the implant,” agrees Dr. Medeiros. “The procedure isn’t painful and they don’t feel anything once the implant is in place; pretty much any discomfort reported was related to the Betadine used for sterilization during the procedure. Patients expressed great interest in being more free of drops with this treatment.”

No More Adherence Issues?

“Lack of adherence with topical drops is a huge problem in glaucoma,” notes Dr. Medeiros. “Data from multiple studies have shown that more than 50 percent of patients are poorly adherent, and this is associated with a worse visual prognosis. Also, many patients can’t put in the drops because of coexisting disorders like rheumatoid arthritis. In many cases, family members or spouses have to put in the drops.”

Dr. Medeiros points out that while a sustained-release implant may address many problems associated with patient application of topical drops, there are caveats. “It’s important to understand that this treatment is not a free pass to not come to see the ophthalmologist,” he says. “Monitoring visual fields and optic nerves will still be an essential component of managing glaucoma in these patients.

“I don’t think this will end the use of eye drops,” he adds, “but having a long-term sustained implant opens up a lot of possibilities. By providing long-term IOP control, Durysta may help address adherence problems, and it may also help to improve the quality of IOP control, with fewer IOP peaks and fluctuations—although this remains to be demonstrated.”

Helpful During the Pandemic?

In the current health crisis, Dr. Craven says the implant could be helpful for a patient forced into isolation in a nursing home. “A patient could achieve IOP reduction without the need for someone to put in drops,” he notes. “We saw patients who were previously using one, two or three medications who did pretty well after receiving the implant and stopping the drops. I’ll be presenting some of that data at this year’s American Academy of Ophthalmology meeting.”

What’s Next?

As with any new treatment option, benefits and drawbacks that might not be revealed by a clinical trial will eventually become apparent in the clinic as doctors begin to use the implant. In the meantime, the current FDA approval only covers a single application of the implant, but other possibilities are under investigation.

“The Phase III clinical trials involved a total of three implants, with one application every four months,” Dr. Medeiros points out. “Multiple studies are ongoing, or being planned, to address the safety and efficacy of multiple implants at different intervals of application. Hopefully, the results from these studies will support an FDA expansion of the current labeling.”

In terms of what else may lie ahead, Dr. Craven says he believes this is only the beginning. “The technology and safety will continue to improve, and IOP control may improve as well,” he says. “Other classes of medications may also be evaluated.” REVIEW

Drs. Craven and Medeiros are consultants to Allergan.

1. Craven ER, Walters T, Christie WC, et al., for the Bimatoprost SR Study Group. 24‐month Phase I/II clinical trial of bimatoprost sustained‐release implant (Bimatoprost SR) in glaucoma patients. Drugs 2020;80:2:167-179. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01248-0.