Ocular surface disease can wreak havoc on our surgical patients. This disorder is the source of thousands of visits each year in our clinics and untold disruptions of our patients' lives. The most common ocular surface diseases we see in our clinic are allergy, blepharitis, dry eye and infectious conjunctivitis, in that order. So many different classification systems exist for these conditions, as well as for dry eye itself, that developing a treatment plan can be difficult.

Thus, determining the underlying etiology is critical in analyzing a patient's potential for improvement. Concomitant ocular surface conditions and irrevocable environmental factors may interact to delay recovery despite appropriate therapy. If elective surgery is indicated, adequate surface recovery is essential to an optimal outcome.

Identifying the Etiology

In classifying the preoperative dry-eye patient, you must first determine whether the condition is associated with a systemic disease such as arthritis, a coexisting ocular surface condition, or with oral medications that can cause or exacerbate dry-eye symptoms. Treatments directed at systemic factors, particularly for anticipated elective eye surgery, may provide relatively rapid results. This can also lead to tightened supervision by the patient's internist and improved oral regimens.

Alternately, a patient's dry eye may be due either to an aqueous or mucin deficiency, or a problem with the eye's lipid layer due to blepharitis—a surprisingly common etiology. In the patient with aqueous deficiency, treatment can involve managing environmental factors and tear conservation efforts such as punctal occlusion.

To replace the tears in a beneficial way, I use preservative-free tears or a vanishing preservative such as Refresh Tears or Optive with Purite. Many patients develop sensitivities to preserved tears, and many over-the-counter products contain vasoconstrictors that are deleterious in both the short- and long-term.

The patient with a combined mechanism problem, such as an aqueous deficiency and evaporative dry eye due to a dysfunction of the tear lipid layer, may benefit from a multifaceted interventional strategy that involves these steps:

• adding Omega-3 fatty acids to the diet;

• using doxycycline, topical azithromycin or medicated lid scrubs to treat the underlying lid disease; and

• adding non-aqueous components to the tear film, such as the hyaluronic acid component found in Blink Tears, and conserving any evaporative tear loss.

Differentiating Severe Cases

Sometimes the physical findings do not correspond to the patient's state of mind or complaints. The patient with an eye that looks severely symptomatic may not complain of severe irritation, while another with what looks like a minor problem can have a high degree of irritation.

I approach these paradoxical cases cautiously. The patient without symptoms may also be neurotrophic, with clearly inadequate corneal sensation. Recent revelations regarding the interactive processes occurring between the ocular surface tissues and the corneal nerves indicate that neurotrophic corneas perpetrate the cycle of aqueous deficiency, inflammation and further decreases in beneficial neurosensory output and epithelial neuropeptide production.

Meanwhile, if a patient has significant punctate keratopathy, I will intervene regardless of how he or she feels. In fact, I worry more about this patient because he or she is more prone to irregular astigmatism, epithelial healing defects and bacterial keratitis.

When to Use Combination Therapies

Any patient with dry eye, whether or not it is due to Sjögren's syndrome, will respond to anti-inflammatory therapy. My first action is to place the patient on a safe steroid such as loteprednol (Lotemax) or cyclosporine emulsion (Restasis). I have drastically altered my approach over the years. I used to employ aggressive tear conservation strategy first with punctal occlusion, but now I perform this step second to prevent trapping poor-quality tears (See sidebar). With each office visit, you can move on to the next level of intervention.

Moving on to Punctal Occlusion

Surgery for ocular surface disease is always adjunctive to medical therapy. The most common ocular surface surgery is punctal occlusion, performed millions of times every year, and probably overlooked just as often. Control of trichiasis can be equally important in less-industrialized countries.

My approach to punctal occlusion is very aggressive. Once you address the quality of the tear film medically, the next step is to enhance and preserve the tear-film quantity.

The initial visit must include an evaluation of the extent of aqueous tear deficiency. If fluorescein and lissamine staining or Schirmer testing indicate significant aqueous tear deficiency, I proceed with collagen plugs.

When inserting punctal plugs, the key is to obtain the tightest fit possible, facilitated by topical anesthesia immediately prior to collagen insertion.

If after a month or two the patient's signs and symptoms have improved, then longer-lasting plugs are indicated. If epiphora truly occurs after the collagen plugs are inserted—an extremely rare finding in a referral practice—then the longer-lasting, semi-permanent silicone plugs are contraindicated. In my experience, most patients have said they had some improvement while the collagen plugs were functioning and sometimes further volunteer that they began to feel worse again when the collagen plugs had presumably fully dissolved.

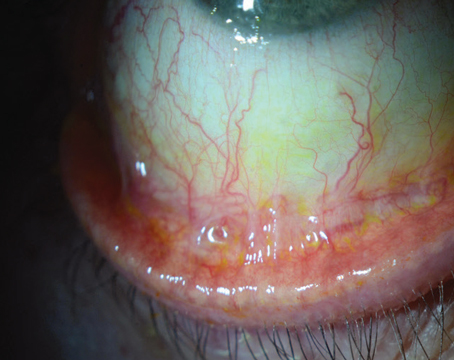

Some patients repeatedly lose their silicone plugs, complain of discomfort or suffer from elevated plug caps. The plugs themselves can harbor makeup and debris, potentially pathogenic bacteria and allergens. Positive lissamine staining nasally, where the plug cap regularly abrades the adjacent conjunctival ocular surface, and nowhere else is a common finding. We prefer plugs with a cap, as plugs without a cap can get trapped in the naso-lacrimal system distal to the canaliculus with the potential for infection. Our oculoplastic colleagues abhor the irrigation process that impacted or infected intra-canalicular design plugs require.

Permanent Cautery

The prospect of permanent cautery increases when problems arise with silicone plugs, however minor, or when the severity of progressive dry eye requires even tighter occlusion of the drainage system. Permanent cautery is a highly successful procedure in practiced hands, despite the momentary local anesthetic pain the patient incurs. The keys to a successful procedure are sufficient analgesia, proper patient positioning and an appropriately fine but durable hyfrecator or thermal cautery tip.

With the patient in the supine position and under minimal oral sedation, place a pledget or cotton swab soaked in 4% lidocaine solution into the nasal canthus and allow it to soak for five to 10 minutes. Next, inject 0.4 mL of 2% lidocaine solution with epinephrine with a 30-ga. needle 2 mm posterior to the punctum (See Figure 1), directly into the interior tarsal conjunctiva. Two methods can help limit the pain of this injection: Apply a cold compress just before the injection, or add bicarbonate to the solution to normalize the pH.

We place the hyfrecator tip deeply into the punctum and the horizontal canaliculus (See Figure 2). The endpoint of the cautery device should produce a brisk, white bubble at the punctum (See Figure 3). We apply a small strip of a topical antibiotic such as bacitracin to control any potential postoperative infection. We warn the patient and his family that a scab may form and then a bruise may appear following the procedure.

We have performed this procedure more than 10,000 times with a minimal and satisfactory level of complications and complaints. We never cauterize both lower- and upper-lid puncta. Recanalization can occur in a small number of patients, necessitating a repeat procedure (which the patient often dreads). Virtually every recipient of this minor operation has been grateful for its positive effect on their dry eye.

Duration of Treatments

I always administer long-term regimens based on what the patient can tolerate and how likely she is to comply. Also, I am committed to maintaining individuals on anti-inflammatory drugs for their lifetimes because of the chronic nature of keratitis sicca. Cyclosporine, which has no known long-term major deleterious effects, is a reassuring therapy. Though many physicians have a minor concern about the long-term safety of low-dose loteprednol, the initial clinical trials and anecdotal reports show minimal toxicity in long-term use.

Dry Eye and Refractive Surgery

I always treat a patient's dry-eye problem before I perform any type of refractive surgery. This strategy can disappoint impulsive patients, but it is necessary for an optimal surgical outcome. Epi-LASEK may present the biggest challenge to the ocular surface epithelium.

Healing an ocular surface can take three months or longer depending on how severe the damage has been, which includes enervation. Again, in such a case, I use Restasis or a steroid or both. If the inflammatory response is severe, I may induce topical therapy with initial steroid treatment and then switch to Restasis for long-term maintenance. Although Restasis reaches its maximal effect at six months, most patients are ready for refractive surgery after one to three months of Restasis therapy.

I tailor postoperative anti-inflammatory therapy depending on the patient's response, underlying risk and the results of the initial Schirmer test and corneal staining, and then titrate accordingly.

Of course, the surgeon must also consider such issues as the expense of frequent medication administration and how it interferes with the patient's daily activities.

Because corneal nerve regrowth takes approximately six weeks in the PRK patient and as long as six months in the LASIK patient, I will maximize refractive patients' therapy for at least that long under reasonably close observation.

Dr. Sheppard is a professor of ophthalmology, microbiology and molecular biology, as well as research program director for ophthalmology residency training at the

Contact Dr. John at (708) 429-2223, fax: (708) 429-2226 or e-mail: tjcornea @gmail.com.