Elevated intraocular pressure is an important risk factor for glaucoma, and the main goal of glaucoma treatment is to control intraocular pressure while maintaining or enhancing quality of life for the patient. To establish guidelines for setting target pressures, 36 Canadian glaucoma specialists attended a series of workshops to review the most recent randomized clinical trials evaluating glaucoma management. They also attended working sessions in which case studies were presented and treatment options were discussed.1

Evidence for Lowering IOP

Several recent studies support the concept of lowering IOP in glaucoma patients and suspects. They include the Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study,2 the Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study,3 the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study,4 and the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study.5,6

The CNTGS found that IOP plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of normal-tension glaucoma. The results also support the aggressive lowering of IOP in patients at risk for progression.

The study initially included 230 patients with normal-tension glaucoma. Of the initial 230 patients, 140 were randomly assigned to receive either restricted medical and surgical treatment (61 eyes) or no treatment (79 eyes).

Target IOP lowering of 30 percent was arbitrarily chosen for those in the treatment group. Only 12 percent of these eyes progressed to further disc damage or visual field loss, compared with 35 percent of the control eyes. Additionally, the time to progression was significantly longer for treated eyes compared with control eyes. However, despite IOP lowering of 30 percent, some treated eyes continued to show progression.

|

|

|

|

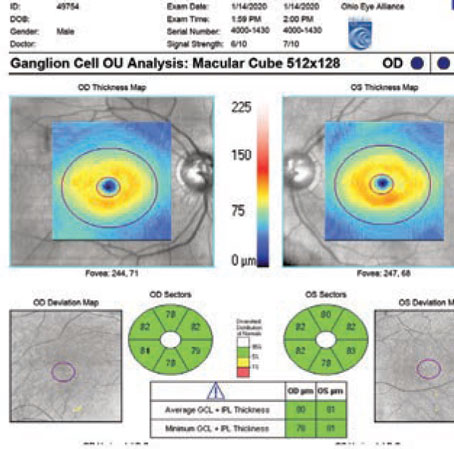

| Figure 1A through D. A 59-year-old Caucasian patient with a relatively normal-appearing right optic nerve (Figure 1A). The patient's pressure was borderline normal, central corneal thickness was normal, and the visual field was also normal (Figure 1C). This eye could be classified as a glaucoma suspect. The left nerve (Figure 1B) demonstrates considerable glaucomatous nerve damage, with a vertical cup-to-disc ratio of about 0.8 and thinning of the superior neuroretinal rim. The IOP was 21 mmHg, the corneal thickness 510 µm, and the Goldmann Visual Field (shown as Figure 1D) demonstrates contraction of the isopters with an inferior paracentral scotoma. Because the scotoma is within the central 10°, this eye is best staged as "advanced" glaucoma. The initial target IOP for this eye would therefore be set in the low teens. This was one of the cases discussed during the target IOP workshops. | |

In addition, not all untreated patients progressed. In fact, 65 percent showed no further progression at five years. This finding strongly suggests that treatment should have minimal side effects, so it does not cause harm or decrease patients' quality of life.

The AGIS found that lower IOP is associated with reduced progression of visual field loss. In this study, the long-term clinical course and prognosis with two surgical treatment protocols were compared in eyes with moderate to advanced glaucoma.

After seven years of follow-up, in a "predictive analysis" of 738 eyes, investigators found a statistically significant worsening of the visual field over six years in eyes with early average pressures greater than 17.5 mmHg compared to eyes with initial average pressures less than 14 mmHg. This worsening was found to become more significant over time.

In the "associative analysis," patients whose IOPs were consistently below 18 mmHg had less visual field loss than those whose IOPs were below 18 mmHg only some of the time. In fact, those with IOPs consistently below 18 mmHg had almost no visual field loss on average.

The CIGTS findings showed that surgical treatment produced greater reductions in IOP compared with medical treatment. This study included 607 patients with newly diagnosed open-angle glaucoma. The study compared initial therapy with topically administered medications versus initial trabeculectomy.

The researchers used the following formula to determine the target IOP range:

Target IOP = (1 – [baseline IOP+ VF score] / 100) x baseline IOP

Target IOP was set aggressively, and patients with a small amount of visual field damage underwent even more aggressive lowering.

Surgical treatment produced IOP reductions of 46 percent compared with 35 percent in patients who underwent medical treatment. Interestingly, there was no difference in visual field protection over the follow-up period of approximately five years.

The investigators concluded that aggressive initial medical IOP management was as effective as early surgical therapy during the follow-up period reported. Additionally, there were no marked differences in quality of life between the groups, although patients in the surgical group did have more ocular surface-related irritation.

The OHTS showed that topical therapy with ocular hypotensive medication was effective in delaying or preventing the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma in certain patients with elevated IOP.

The study included 1,636 patients with elevated IOP but no evidence of glaucomatous disc or field damage. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either treatment or observation. The treatment goal was to achieve an IOP reduction of 20 percent or more and an IOP of less than 25 mmHg. At 60 months, patients in the observation group had a greater cumulative probability of manifesting primary open-angle glaucoma than treated patients.

Developing Guidelines

Before developing working guidelines, current Canadian perspectives were put to practical application through a case-study format. The cases varied widely, from very complex to relatively simple and from suspects to patients with early onset glaucomatous optic neuropathy to patients with advanced glaucoma. However, regardless of the complexity of the case, consensus about the target IOP range was achieved. The process clearly illustrated that it was possible to develop guidelines for setting target IOP range.

Establishing a Range

Before establishing a target IOP range, an accurate baseline IOP is needed. While a single applanation reading may be sufficient when establishing baseline IOP, it is helpful to have more than one IOP reading. This can include previously documented IOP values from the referral source or a diurnal tension curve.

Physicians should thoroughly assess the patient to make sure that all relevant risk factors and treatment considerations are taken into account when setting the initial target IOP range. The initial assessment should include the following components:

• history taking: ocular, systemic, and family;

• ocular examination: IOP measurement, gonioscopy, documentation of baseline optic nerve appearance;

• testing of the visual fields: It is important to obtain at least one reliable baseline visual field consistent with the optic nerve appearance; and

• additional investigations as appropriate: Imaging of the optic nerve and nerve fiber layer, measurement of the central corneal thickness.7

Staging Criteria

After establishing a baseline IOP, the next step in determining a target IOP is to stage the eye. It is important to evaluate each patient and each eye individually, because glaucoma is often quite asymmetric. In some cases, such as pseudoexfoliation glaucoma, one eye may be quite advanced, while the other eye is clinically unaffected.

Participants in the workshops developed recommendations for staging an eye at risk for or with glaucoma. Eyes are staged as suspects, those with early disease, those with moderate disease, and those with advanced disease.

Glaucoma suspects will have at least one of the following: IOP higher than 22 mmHg (adjusted for pachymetry if available); suspicious disc or cup-to-disc asymmetry greater than 0.2; or suspicious visual field defect on Humphrey 24-2 (or similar) testing.

Those with early disease will have early glaucomatous disc features (e.g., cup-to-disc ratio of 0.65 or less) or a mild visual field defect not within 10° of fixation, or both.

Those with moderate disease will have moderate glaucomatous disc features (e.g., cup-to-disc ratio of 0.7 to 0.85) or a moderate visual field defect not within 10° of fixation, or both.

Those with advanced disease will have advanced glaucomatous disc features (e.g., cup-to-disc ratio of 0.9 or greater) or visual field defect within 10° of fixation, or both. Also, consider the baseline Humphrey 10-2 visual field (or similar).

Ophthalmologists will need to apply their own judgment, so we haven't given strict criteria regarding which category to place a patient in. We felt that some latitude should be given to the ophthalmologist to exercise judgment based on the nerve and the field. Special consideration should be given to disc size when looking at the cup-to-disc ratio and neural rim area, because a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.7 may be physiological in a large optic nerve, but signify glaucomatous damage in a small nerve.

Glaucomatous Disc Features

The recommendations use the following features to help define a glaucomatous disc:

• increased cup-to-disc ratio, significant disc asymmetry;

• decreased or documented change in neuroretinal rim area;

• notch of neuroretinal rim;

• saucerization of neuroretinal rim;

• flame-shaped disc hemorrhage;

• nerve fiber layer loss; and

• 360° peripapillary atrophy.1

Target IOP Range

Based on the staging of the glaucomatous eye, the workshop participants developed suggested upper limits of the initial target IOP range for each eye. The lower limit of target IOP is episcleral venous pressure.

For a glaucoma suspect, if the decision is made to treat, the suggested upper limit of the initial IOP range is less than 25 mmHg with reduction of at least 20 percent from the baseline IOP, which is based on OHTS. For a patient with early disease, the upper limit is less than 21 mmHg with reduction of at least 20 percent from baseline. This is based on the CIGTS and expert opinion. It is important to note that at the time the workshops were held, the results of the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial (EMGT)8 were not available. Based on the EMGT, it is quite reasonable to aim for a reduction of at least 25 percent from baseline. For a patient with moderate disease, the upper limit is less than 18 mmHg with reduction of at least 30 percent from baseline IOP. This is based on the CNTGS and AGIS. For patients with advanced disease, the upper limit is less than 15 mmHg with reduction of at least 30 percent from baseline IOP, which is based on AGIS and other data.

| Progression Risk Factors |

| Risk factors for progression that may modify the initial target IOP range include the following: |

| • Presence and severity of damage to involved or fellow eye |

| • Rapid rate of progression of damage to involved or fellow eye |

| • Family history of or genetic mutation predisposing to early onset disease or severe disease, or both |

| • African ancestry |

| • Age and life expectancy |

| • Vascular risk factors: disc hemorrhage, nocturnal hypotension, migraine, Raynaud's disease, diabetes mellitus, previous vein occlusion |

| • Large fluctuation or instability in IOP (e.g., IOP spikes, pseudoexfoliation syndrome) |

| • Poor follow-up |

| • Axial myopia (speculative) |

It is important to think of the concept of establishing a target pressure as dynamic, not a rigid number. Target IOP range requires ongoing evaluation and should be re-evaluated at each follow-up visit. Based on the re-evaluation, the physician may decide to adjust the target IOP range. If there is evidence of progression in the optic nerve or a reproducible change in the visual field despite achieving an IOP within the target range, the target IOP range should be lowered. On the other hand, if the physician determines that achieving the target IOP range caused unacceptable ocular or systemic side effects, the target range may be increased.

Dr. Damji specializes in glaucoma at the University of Ottawa Eye Institute and is director of the Glaucoma Service. Ms. Bovell is the study coordinator for clinical and genetic studies related to glaucoma at the University of Ottawa Eye Institute. Contact her at (613) 737-8629 or abovell@ottawa hospital.on.ca.

Many glaucoma colleagues participated in the development of these guidelines. A full list is included in reference 1. These workshops were supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Allergan Canada Inc.

1. Damji KF, Behki R, Wang L, for the Target IOP Workshop participants. Canadian perspectives in glaucoma management: setting target intraocular pressure range. Can J Ophthalmol 2003;38:189-197.

2. Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group (CNTGS). The effectiveness of intraocular pressure reduction in the treatment of normal-tension glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 1998;126:498-505.

3. AGIS Investigators. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;130(4):429-440.

4. Janz NK, Wren PA, Lichter PR, Musch DC, Gillespie BW, Guire KE, et al. The Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study: interim quality of life findings after initial medical or surgical treatment of glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2001;108:1954-1965.

5. Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, Johnson CA, Keltner JL, Miller JP, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120(6):701-713.

6. Gordon MO, Beiser JA, Brandt JD, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, Johnson CA, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: baseline factors that predict the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:714-720.

7. Damji KF, Muni RH, Munger RM. Influence of corneal variables on accuracy of intraocular pressure measurement. J Glaucoma 2003;12(1):69-80.

8. Heijl A, Leske MC, Bengtsson B, Hyman L, Bengtsson B, Hussein M; Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial Group. Reduction of intraocular pressure and glaucoma progression: results from the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120(10):1268-1279.