|

Like your peers, you always strive to excel as a diagnostician, clinician and surgeon. But what if your patients are healthy yet your practice isn’t? What if it’s suffering from a bad case of ill will caused by disgruntled patients and the typically related issue of unhappy staff? How do you recognize the symptoms, correct underlying problems and ensure that the improvements you make stay in place?

In this article, surgeons and practice management experts offer advice that you can use to unmask these problems and make needed changes, which, they argue, can help you nip reputation-damaging episodes in the bud.

Remembering to Ask

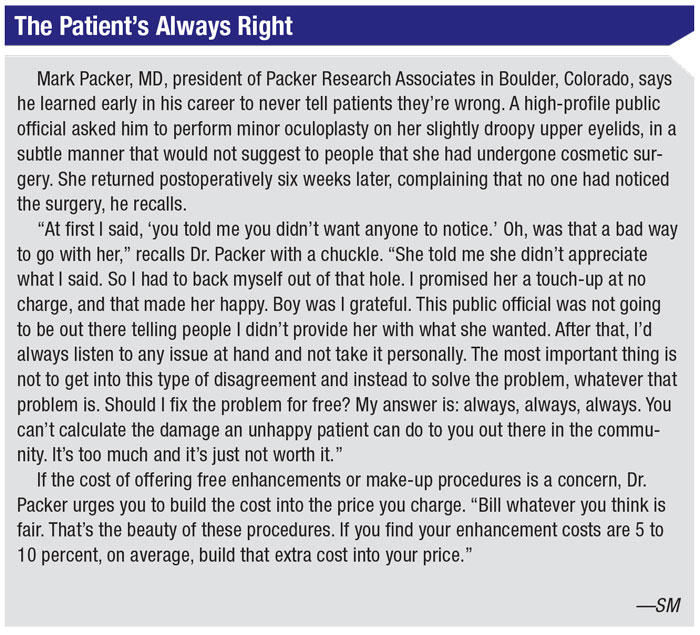

“The best way to find out if you have any of these problems is to ask,” says Mark Packer, MD, president of Packer Research Associates in Boulder, Colorado. “The problem is that people won’t tell you the truth directly because they feel vulnerable, whether they’re patients depending on you to perform good surgery or members of your staff who want to keep working for you.”

Besides his background in private practice and his current role as a monitor for FDA trials, Dr. Packer works on practice improvement programs on behalf of drug and equipment makers, helping practices to optimize the patient experience—or, in the parlance of practice management experts, the “journey.” He notes that “using an anonymous survey of your patients can help a lot. At the end of the visit, hand the patient an envelope containing the anonymous survey and say, ‘I’d really appreciate it if you’d fill this out truthfully. I’ll never know what you say personally. I’ll just see percentages of survey respondents who answer questions different ways. There are 20 items on there, so it shouldn’t take you long to fill it out.”

Dr. Packer recommends asking questions that will help you find out if your patients feel you listen to them and provide clear explanations. Then you can ask about your waiting room: “Was it comfortable? Were the front office staff and receptionist friendly? Did they take care of your questions? If you had an insurance issue, did the staff offer you help with that?”

The top complaint Dr. Packer’s practice received on the surveys every year—echoed by other doctors and experts interviewed for this article—focused on long waiting times. “We established a never-attainable goal of zero waiting time and were able to get it down from more than 20 minutes to five minutes,” says Dr. Packer. “We worked with each technician to streamline the performance of about 10 tasks, such as pressure checks and manifest refractions, done before the patient was seen by the doctor. Then we manipulated the schedule so a technician would do, on average, one new patient and three returning patients each hour. That’s what we could comfortably do. Of course, you always had emergencies and add-ons, but we tried not to let them disrupt our flow, once we implemented these changes. It made a big difference.”

Kendall E. Donaldson, MD, MS, a professor and medical director at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Plantation, Florida, likewise recommends you rush to reduce waiting times.

“Patients can love us and they can have perfect vision after surgery, but if we make them wait too long, that is not tolerated,” she says. “In our surveys, wait time has the been the biggest source of dissatisfaction.”

|

Dr. Donaldson notes that her practice has benefited from training by the renowned Disney Institute, which helps develop high-performing staff, grounded in superior customer service, competence and confidence. “From the very highest level of administration down to the technicians and front-desk people and support staff, I believe it’s very important for everybody to remain on the same page so that patients get the same message from the time they enter your practice until they leave,” she says.

South Florida surgeon Alan Aker, MD, says he learned to treat all patients the same early in his career when he performed cataract surgery on one of the leading cataract surgeons in history. “He said, ‘Alan, you have to treat me like any other patient,’” recalls Dr. Aker, who owns and operates the Aker Kasten Eye Center with his wife, Ann Kasten, MD, in Boca Raton. (Dr. Aker asks that the prominent surgeon, now deceased, not be named.) “I can still hear him saying it. And he was exactly right. He realized that I was changing the way I did things because it was him. So now we don’t change anything for any patient. We treat every patient the way we would treat a governor or a princess—and we’ve treated both. Whether patients are our mission cases, for which we seek no compensation, or international royalty, we treat them all in a way that we hope will make their heads turn.”

|

Alternative Insights

Daniel Fernandez, chief experience officer at the Symphony Agency, Tampa Bay, Florida, consults with ophthalmologists to optimize their patients’ journey from initial appointment to continuity of care. The goals are to increase patient satisfaction scores, throughput, profits and retention of patients and staff, as well as to decrease errors. “The most common mistake a practice can make is to focus solely on patient feedback,” he says. “The best-performing practices understand that exceptional care is delivered when the patients, caregivers and leadership teams’ expectations are all in alignment.”

When trying to help a practice bolster its patient satisfaction scores, he administers what he calls a rapid reputation audit, which includes the following:

- experience surveys, gathering input from patients, caregivers and the practice’s leadership team;

- assessment and aggregation of all online reviews of the practice;

- assessment of social media presence, including how well the practice is engaging with patients and potential patients;

- a competitive analysis; and

- a review of the good and bad information about the practice and its doctors that might surface during a Google search.

Thomas P. Jeffrey, president of the SullivanLuallin Group, a consulting firm in San Diego that uses a variety of tools to help ophthalmologists improve the patient experience, says practices need to faithfully follow “service protocols” as rigidly as they follow clinical protocols.

“I would say that it doesn’t really matter if people in the office are having a bad day,” he notes. “It comes down to whether you’re following your protocols. That includes smiling, warmly greeting patients and calling them by their names. We recommend putting a clear model in place for your practice to follow. Your team members must know what you expect of them and they must know how to meet your expectations.”

|

After many years of doing patient surveys and working with practices, Mr. Jeffrey says his company has found that employees typically respond positively to supportive feedback more than to compensation. Patients, in turn, mirror this response because they tend to judge you by how you treat your employees.

“We talk about praise in public and counsel in private,” he adds. “A warm hand-off of the patient between the staff and the physician—those types of things.”

Your direct personal approach to the patient is also critical, according to Andrew Golden, MD, a family practice physician and medical director at SullivanLuallin. He urges you to follow the time-tested advice of Sir William Osler, who helped establish the field of internal medicine, co-founded Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in 1893 and helped develop the system of clinical medical education used to this day.

“Osler said, ‘The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease,’” Dr. Golden recalls. “Being an excellent diagnostician, clinician and surgeon is not enough anymore, if it ever was, considering Osler said that it wasn’t enough more than a century ago. You really have to provide individualized care to make a difference to the patient.”

Are You the Problem?

Your demeanor can significantly affect how your patients rate your practice. Just ask Dr. Packer. “One of my partners was impossibly taciturn and impatient with people, acting as if they should just take his advice without asking any questions,” he recalls.

On the practice surveys, the partner consistently received zeroes and ones on a scale of one to five for most questions. “It was incontrovertible evidence that patients didn’t like his approach,” says Dr. Packer. “I knew it first-hand because many patients switched to me, telling me that doctor X never took enough time with them.”

Like Dr. Packer, Dr. Donaldson recommends carefully evaluating objective data about how patients respond to you. “You think you’re doing great in this area until you start looking at the numbers,” she says. “Analyzing aspects of the care you provide in detail is very important, whether it be the patient experience or the surgical outcomes.”

As a provider in the University of Miami Health System, Dr. Donaldson receives the results of monthly surveys that present her with a percentage-based overall rating, plus a finding that shows what percent of survey respondents would recommend her practice to a potential patient.

More specifically, the scores show whether a doctor:

- provides instructions that are easy for the patient to understand;

- knows important aspects of the patient’s medical history;

- respects what patients say;

- spends enough time with the patients.

“I get a report on my staff and me, so I can see how we’re doing,” she says. “This objective information is very helpful to us in making positive changes.”

The objective insights that most helped Drs. Aker and Kasten came from a pricey consulting company that parked at their practice for more than a year, 35 years ago. “At first, I thought they were too expensive,” admits Dr. Aker. “But they were more than worth it.” The consultant recommended elimination of the eye center’s pyramid management structure, suggesting the creation of five self-managing teams that allowed the husband-and-wife surgeons to focus almost exclusively on providing quality care. With accountability spread throughout the center, Dr. Aker says their practice self-downsized from 72 to 56 employees who now provide more efficient care that better meets the needs of patients.

“We’d been operating under the Peter Principle,” he reflects with a laugh. “Instead of getting rid of employees who weren’t working out in particular positions, we were pushing them to the side and giving them other jobs, then hiring other people to replace them. Now, we let our staff take care of managing what needs to be managed in their respective areas and, as a result, the patient experience has never been better. We used to look for people with good experience and skills and try to train them to be nice. What you want to do is look for nice people and train them to be good at what they do. If a new employee has a smiling face and the right attitude, they can learn fast. Our practice is now 40 years old and we’ve never had a lawsuit.”

|

Mr. Fernandez says ophthalmologists often fail to appreciate deficiencies in their management or personal style that could affect patient satisfaction. “When your physician reviews speak to your ability to deliver exceptional outcomes but mention nothing about personal demeanor, this is usually a good indicator that things need to change,” he says. “While patients may respect your expertise, what they’re looking for these days are doctors and support people they can relate to. I suggest looking for simple ways to connect.”

When doing observational work in practices, Dr. Golden asks ophthalmologists to rate the importance of patient satisfaction on a scale of one to 10. “That question is critical,” he says. “I find that physicians who aren’t very good at satisfying patients rate patient satisfaction as a lower priority. Cognitively, they have to change that priority or they’re never going to improve.”

Changing Things Up

Sometimes increasing patient satisfaction can boil down to revamping your office layout, patient flow and other aspects of your physical practice. Ophthalmologists and consultants weigh in on what modifications can produce the best results.

“In our case we were stuck with what we had—one waiting room and no dilation room—because of space limitations,” says Dr. Packer. “We gave patients something to do while they were dilating, such as iPads with questionnaires that would help them understand more about what might have been affecting them, such as dry eye, cataracts and other conditions.Once patients were seen by technicians and they were waiting for a doctor, if they were doing something that was tailored to them personally, it kept them busy and made the time go by faster.”

When modifying her practice, Dr. Donaldson responded to an analysis of waiting and processing times. “We now have all the technicians clustered in one area and all of the physicians together in another area,” she says. “We used to have a technician stay with the physician and patient.”

The practice also now clusters similar types of patients. “For example, ocular surface disease patients [cluster together], allowing us to concentrate a certain period of time on those patients,” she continues. “We put the postoperative patients together so their visits can be better expedited. We schedule certain half-days for refractive patients. By grouping these patients by half-days or by other time frames needed to ensure efficient, high-quality care, you can expedite their flow through the office.”

She also recommends that her colleagues visit other practices to see how the practices handle schedules and patient management. “It gives you another perspective on what you’re doing,” she notes. “You tend to get boxed in on what you’re doing and continue to make the same mistakes, doing things the same way, just because you haven’t been exposed to another way of doing it.”

|

Time management and efficiency should be constantly measured and improved. “Seconds add up to minutes, saving time that increases productivity and time spent with patients,” says Mr. Jeffrey of the SullivanLualin Group. “The physician shouldn’t be walking longer distances than necessary to reach patients. One effective approach is setting up access to the EHR in the hallway. The doctor can more efficiently gather needed information before entering a room to see the next patient.”

Constantly setting and meeting patient expectations is also important. “For example, you might need to tell a patient that the doctor has had to do emergency surgery and will be 45 minutes late,” says Mr. Jeffrey. “Offer the patient the opportunity to leave the office and receive a text message when the doctor’s ready. Or, reschedule the visit. Most patients will say they’ll just wait until the doctor is ready. Allowing the patient to participate in the decision-making process can make a positive difference, fostering more satisfaction. The physician should also apologize for making the patient wait. There’s a tendency when things aren’t going smoothly to shy away from this type of simple communication. But this is when you want to be more outgoing with patients. Also, make sure the right hand knows what the left hand is doing. If a delay results in a patient not getting a test, for example, that’s really going to affect quality of care. All these little things go a long way toward achieving success.”

Managing Disgruntled Patients

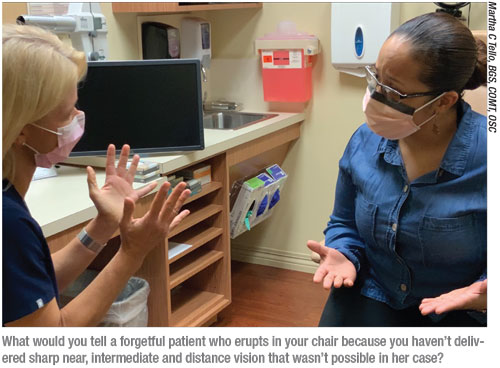

Many patients don’t remember—or at least don’t appreciate—that you told them preop about the risks and less-than-perfect results that were possible. How do you avoid these communication failures and resulting patient complaints?

“The main thing here is setting expectations beforehand and emphasizing if the patient has an extra risk factor, such as pseudoexfoliation syndrome, a history of Flomax treatment in a patient who has a non-dilating pupil, or macular degeneration in a patient that makes implantation of a premium IOL inappropriate for him,” says Dr. Donaldson. “You really have to spend extra time emphasizing these points and documenting in the chart what you’ve communicated to the patient. I’m also careful to repeat the same general message about cataract surgery and premium IOLs. And then I say, ‘In your case, this is what I recommend and this is the special risk factor for you.’ I know exactly what I’ve said to the patient because I’ve scripted it.”

When one of Dr. Aker’s patients reports dissatisfaction to him, he focuses intently on the patient. “I look the patient right in the eye and I say, ‘The first thing I want to get across to you is that I am on your side. I want to hear everything you have to say. I’m going to do everything in my power to make this right and make you happy.’ We’ve given patients back money paid for premium IOLs when they’ve got what on paper looks like a perfect result—good distance, intermediate and near vision.”

Dr. Aker says he goes to any length to meet a patient’s needs, including giving every postop patient his mobile phone number so the patient can call with questions. “I call every patient the night of surgery to make sure he or she is doing okay,” he adds.

Despite Best Efforts

The issue of troubled patients will always persist, surgeons and consultants say. It’s best to have a coordinated strategy for handling them.

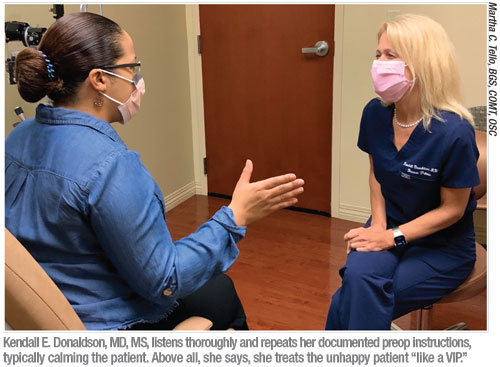

“When you recognize that a patient who has undergone surgery or medical treatment is unhappy, you have to rise to another level of care and treat that patient like a VIP,” says Dr. Donaldson. “I have a staff member who is very patient- and customer-service oriented. I assign her to patients who need this extra care. She makes sure the patient doesn’t wait, spends extra time talking to the patient and then she comes directly to me. I like to get a feel for how the patient is coming along. I want to make sure the patient is getting the right level of customer service.”

|

Dr. Packer followed the same approach when he was in practice. “We had an unofficial policy on this,” he says. “If patients seemed like they were going to be disruptive, you never waited. You took them from the technician working them up directly to the doctor. You don’t let them back out into the waiting room, where they could fill other patients’ heads with negative comments.”

Dr. Aker says his practice schedules disgruntled patients for the end of the day, when they’re less likely to negatively affect other patients. “They’re marked on our schedule as patients requiring special attention,” he notes. “When they arrive, they’re quickly escorted away from other patients. When they get worked up in the back, everyone is aware we’re giving this patient a lot of TLC.”

He recommends searching for problems behind problems. “Often, the disgruntled patient is somebody’s mother and the kids have abandoned her, “he says.” Or the kids don’t call. The support that was there is gone. The husband may have left or passed away, and she’s holding all the bad cards. She just feels like no one cares about her. We want to love these patients to the point of confusion.

“We had one woman who was notorious in her community for being unhappy about everything. We ended up becoming very good friends with her. She had no choice. Sometimes, when these patients leave after a visit or a procedure, it’s almost like they don’t want to leave.”

Worth Your Trouble

Turning unhappy patients into goodwill ambassadors for your practice might not affect your surgical outcomes. However, in this era of patient-centered care and the increasing influence of patient-reported outcomes, experts say it should be an important objective. Vocal complaints and negative Yelp reviews can strike like lightning in a world connected by tweets, text messages and online postings. Beyond this reality, the effect of patient satisfaction on your status as a provider dependent on payments from the federal government and health insurance plans demands serious consideration of patient satisfaction.

“The days of paper surveys that collected dust in the corner of the administration office are long gone,” says Mr. Fernandez. “Now, more than ever, we must focus on delivering exceptional human-centric care to patients if we want to retain them. They know they have choices.”

Dr. Golden notes that a lot of reimbursement matters depend on patient satisfaction scores. “There are well-established outcomes in effective patient communication and enhanced patient satisfaction,” he says. “Achieving these outcomes is becoming as important as achieving clinical outcomes. It leads to fewer malpractice lawsuits and increased provider satisfaction, and in the end, a lot less reworking and wasted energy as well.” REVIEW