The demand for corneal refractive surgery has been growing year by year, and laser vision correction volume topped out at 833,000 cases in 2021, according to the American Refractive Surgery Council. Whether patients come see refractive surgeons out of their own curiosity or because they know a friend or family member who had a procedure, the screening process must be thorough. Technologies and techniques have improved greatly, but the threat of post-surgery ectasia is always in surgeons’ minds, and the more preop data they have about patients the better. We spoke with some experienced refractive surgeons about their screening protocols and what influences their decisions to perform LASIK, PRK or SMILE.

|

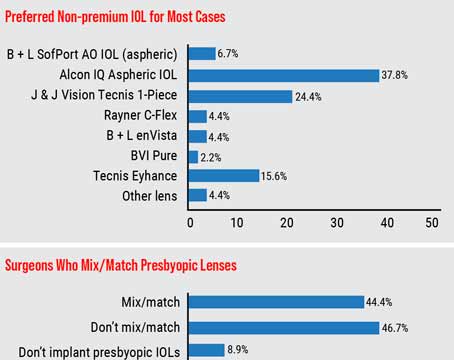

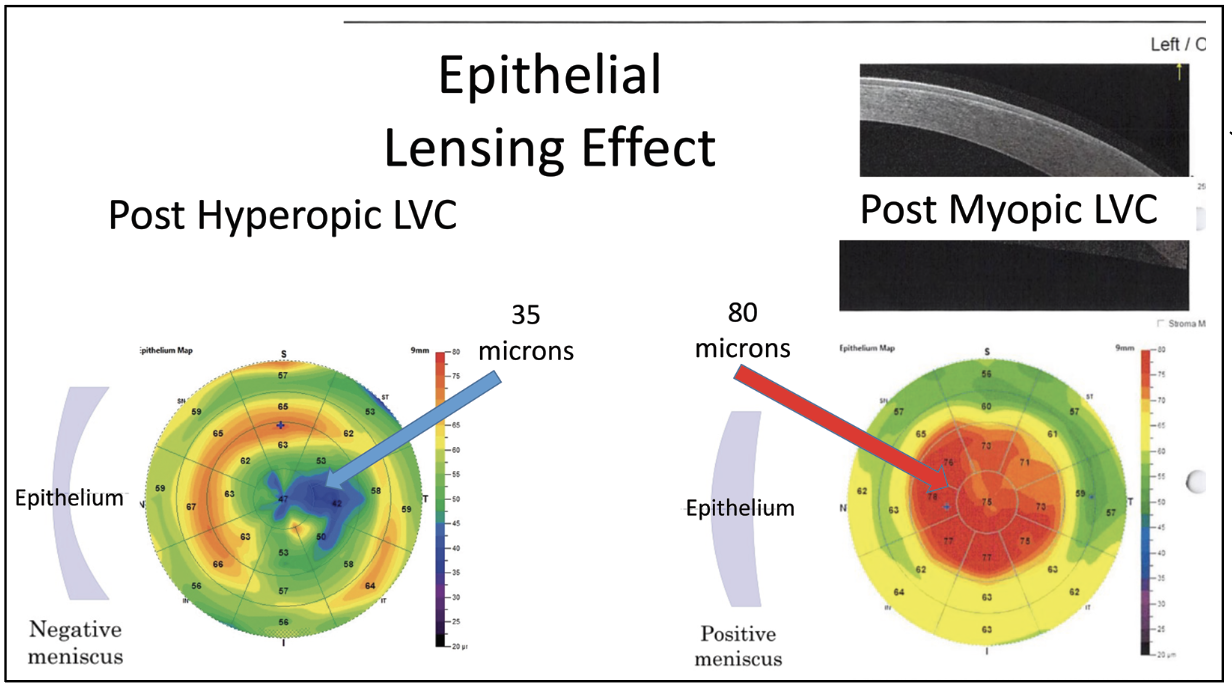

| Epithelial mapping is not only useful prior to laser vision correction, but also when planning enhancements. Epithelial thickness can be quite variable after LVC, but typically is thickened after myopic LVC and thinned centrally after hyperopic LVC. Removing this epithelium can produce refractive surprises that may take many months to resolve. (Courtesy of Steven Dell, MD.) |

Patient History And Expectations

Although technology is a major aspect of the screening process, surgeons must also take cues from conversations with the patient to guide their decision. Not surprisingly, many patients come in requesting and expecting LASIK specifically, unaware of the qualifying factors for it or that there are other options.

“LASIK has become a household name,” says Sumitra Khandelwal, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology at Baylor College of Medicine, Cullen Eye Institute. “It’s kind of like Kleenex for soft tissues. Even to this day, most patients come in asking for LASIK because they heard I did it on their friend, sibling or parent, but I’ll often tell them, ‘No, I did PRK,’ and they don’t even realize what their friend had done. It’s really interesting how that stamp gets put on all corneal refractive procedures, even when somebody didn’t have LASIK.”

It can be eye opening for patients to learn about the alternatives to LASIK and what goals each surgery can achieve. Sometimes surgeons have to deliver a reality check.

“The first conversation I have is about the patient’s expectations,” says Brad Kligman, MD, whose practice is in Manhasset, New York. “Even before I specifically point to the imaging, I take into consideration the patient’s age and what they’re coming in expecting to achieve. At least once a month, I have someone in their late 40s/early 50s who are now presbyopic, hates that they have to use their reading glasses, and has the impression that LASIK can fix all of that. I have to explain to them that ‘Yes, we could correct your vision to allow you to read, but really the two options for that are to correct both eyes for near and take away your distance vision completely, or correct one eye and create a monovision situation,’ which some people are very happy with, but a lot of people, once they hear that we can’t restore their eyes to when they were 20 years old with perfect distance and reading vision in both eyes, they say ‘Oh, that’s not necessarily what I was looking for.’”

John Doane, MD, FACS, of Kansas City, says these patient-centric factors have to be considered. “You have to consider why this person is here. What do they want to get out of the surgery? How old are they? What’s their job? You have to understand where people are in their life cycle as far as accommodation, and this sets the tone for what you’re going to be counseling them on,” says Dr. Doane. “If someone is 50 and they’re nearsighted -2 and they want to see great at distance but they don’t want to wear glasses when using the computer, well that’s not going to work. You have to either change expectations or simply not do surgery.”

Patients are often screened in advance by technicians who ask multiple questions about their health and ocular history, but Dr. Khandelwal says she likes to hear the answers for herself. “It’s amazing how many times they’ll say one thing to the technician and then when I ask them again, they’ll change their minds about the answer,” she says.

After the usual, “What brings you in today?” question, here are examples of things Dr. Khandelwal will ask, along with her reasoning:

• What bothers you about contacts or glasses or both? “I like to understand if they’re truly contact lens-intolerant or just don’t want to wear glasses and contacts,” says Dr. Khandelwal. “That mentally leads me to look for signs and symptoms of dry eye and allergies, but also just helps me to be aware of the fact that they may be somebody really sensitive about things around their eyes, or if they’re a pretty long-term contact lens wearer I know that they’re usually a pretty cooperative patient when it comes to doing things around the eye. When they tell me something like ‘I hate it when things are around my eye,’ we’re going to be careful about how we approach their eye.”

• Has your prescription changed or not? “That’s actually the question where a lot of times my technician will ask it, and then my technician will check their wear (current prescription that they walk in with) and then when I talk to the patient, they’ll say, ‘You know what, actually, my vision prescription has fluctuated a bunch over the last couple of years.’ This is a question that sometimes needs to be addressed one more time because they start to think back a little bit,” she says. “Also, if they’re asked if their glasses have changed but they’re a contact lens wearer, they often don’t change their glasses for years. And it’s hard to know how much your contact lens prescription has been tweaked. I make sure the technician asks about both glasses and contact lens prescriptions.”

• Do you have a family member who’s had refractive surgery and had issues with their eyes, such as keratoconus? “It’s an important thing to document because we do know that ectasia has some genetic component to it,” Dr. Khandelwal says. “If they have a sibling or a first-degree family member who has keratoconus, I’m going to look at their risk factors just a little differently.”

• When do you get dry eye? “As I go through the typical dry-eye questions, I’ll ask if it’s only when they wear contacts, or just when they wear their glasses, and the answer guides me,” she says.

Dr. Khandelwal will also look for red flags during a clinical exam. “I look for things like blepharitis, scarring of the eyelids, sleeving on the lashes, checking that they don’t have something like Staph blepharoconjunctivitis or Demodex,” she says. “Make sure they don’t have a lot of inflammation on the conjunctiva, no capillary reaction from severe allergies. The cornea should be nice and clear. Check that they don’t have a bunch of blood vessels from contact lens overuse or tight-fitting contact lenses. I do that because those patients are tough—if you have blood vessels that are within the area where you’re going to create a flap, that can cause bleeding and heme, and those can be a challenge to then continue the procedure.

“Make a note if they have any corneal scars,” Dr. Khandelwal continues. “Maybe they were a previous ulcer patient, maybe they had trauma to their corneas from something mild, but it left a residual slight scar. You have to be careful with those also with LASIK because when you create the flap with the femtosecond, you can get things like vertical gas breakthrough.”

|

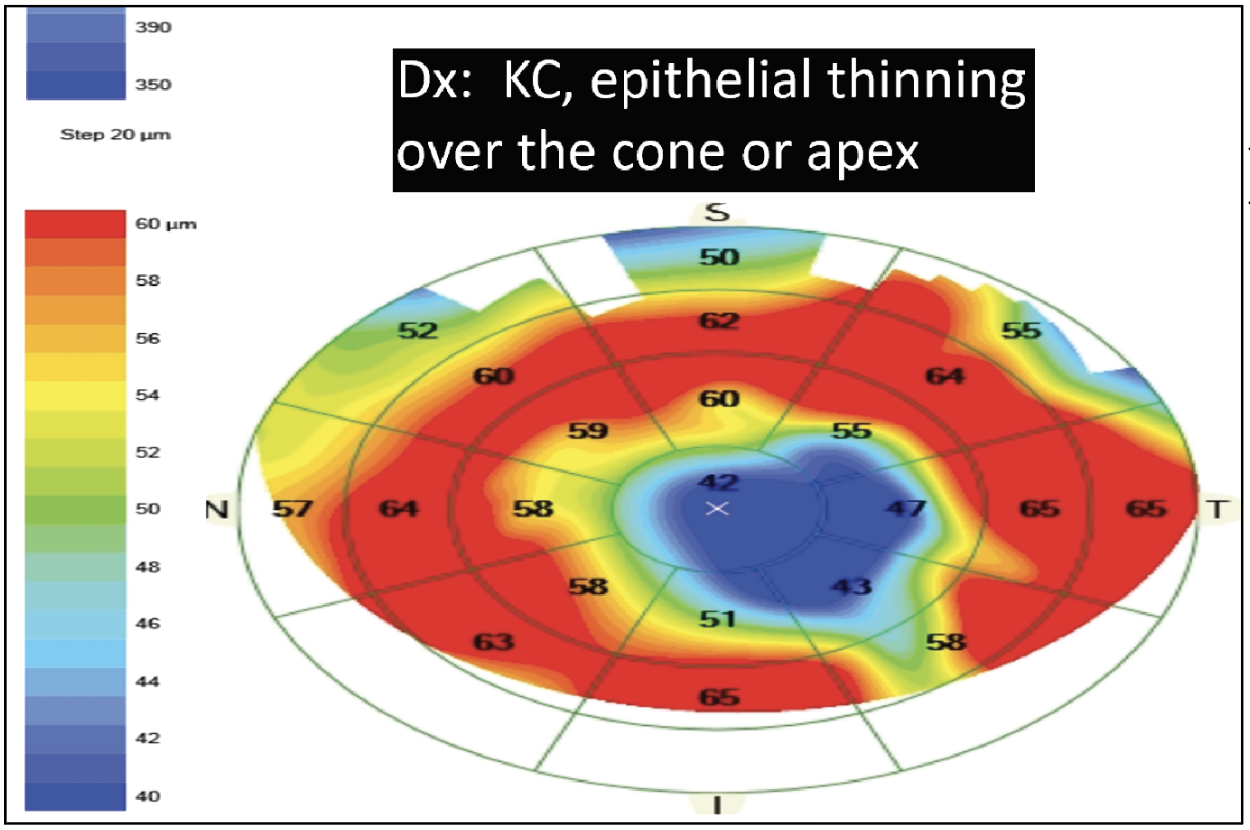

| This image shows a case of keratoconus with epithelial thinning over the apex, which tells the refractive surgeon that lamellar refractive surgery shouldn’t be performed. (Courtesy of John Doane, MD, FACS.) |

Essential Diagnostic Exams

Innovations in the field of tomography, topography, pachymetry, epithelial mapping and more have contributed to the accuracy of refractive screening.

Steven Dell, MD, medical director of Dell Laser Consultants in Austin, Texas, started performing laser vision correction when it was first FDA approved and recalls when surgeons didn’t have that many tools at their disposal. “Topography was really the only thing we had to screen out whether a patient was or wasn’t a candidate, along with pachymetry—and in the earliest days of laser vision correction we were using ultrasound pachymetry,” he says. “Now, most of us wouldn’t feel comfortable performing laser vision correction unless we had not only a topographical image of the interior surface of the cornea, but also views of the posterior elevation of the cornea with devices such as the Pentacam or Galilei. Those have become much more important. For some period of time we were much more concerned about corneal pachymetry, but I think we’ve become a little less concerned about overall corneal thickness and much more concerned about whether or not the cornea is topographically normal.”

Dr. Kligman, who says he’s grateful to have had access to these advanced technologies for the length of his career, says he has always used the Pentacam. “It gives me a complete view of the curvature and thickness profile of the cornea vs. piecing together interior topography with ultrasound pachymetry, which gives you a good idea of the shape of the cornea, but it missed out on some of the more subtle hints of a weaker or ectatic cornea,” he says. “That allows us to rule them out with a little bit more competency the patients that might be at higher risk for ectasis beforehand, and even with the Pentacam, we have more advanced analysis with the Belin-Ambrosio ectasia risk score and the ABCD keratoconus staging system.”

The Belin ABCD keratoconus staging system considers posterior curvature and thickness measurements based on the thinnest point, as opposed to the apex, which may be a better indicator of keratoconus and related ectatic diseases.1

In addition to the Pentacam, Dr. Kligman does an OCT of the macula. “I always want to see up front if there’s anything unusual or funny going on in the retina that would impact the outcome of the LASIK so that again we can set expectations and say to the patient, ‘You have this going on in the back of your eye which isn’t impacted by LASIK and might still cause some limitations based on that,’ or ‘You’re ruled out because of this.’ Having the OCT to do a quick scan of the retina even before you get to the dilated exam also helps set expectations or eliminate patients upfront in the earliest stages of the evaluation,” he says.

Dr. Doane says corneal topography and anterior-segment OCT are the two most important components he considers. “Does the cornea have normal anatomy and does it have appropriate thickness? Does it have any signs of forme fruste keratoconus (FFKC)? You’re looking for anything that would show a sign for potential ectasia or anything topographically that makes you think this person may be a FFKC patient. If they are, they’re unsuitable for a lamellar refractive procedure,” he says.

“We do Placido topography on the patient, which gives us the mires, which yield quantitative information as well as qualitative information as far as their ocular surface disease goes,” says Dr. Khandelwal. “If the mires are distorted in any location, if they’re irregular, we can start to think about what might be causing that, such as ocular surface disease or maybe ectasia. You’re not going to get the ectasia necessarily screened out from the Placido image, but certainly finding little patches of dryness is helpful. We do tear breakup time on the patients, just to understand what that is.”

It’s a good idea to double or triple check measurements on patients, too, she continues. “A few things that might cause ocular surface disease can include contact lens warpage, so if a patient over-wears contact lenses or if it was a tight fit to begin with, especially with toric soft lenses, the reality is that it may take longer to get the cornea regular,” Dr. Khandelwal says. “This is why we’ll often do two measurements at a minimum for patients. We use iDesign for example, and I pick the measurement that makes the most sense, but I need to have two measurements that really match up nicely in order to proceed with the procedure.”

Another tool in refractive surgeons’ armamentarium is epithelial mapping. Although not widely available, Dr. Dell believes it’s within the reach of every refractive surgeon and can be helpful in determining whether patients really are good candidates for laser vision correction. “It can give a better picture of whether or not a patient’s topography is abnormal because of a tendency towards keratoconus or FFKC, or whether it’s something simply related to dry eye,” he says.

“Epithelial mapping in particular is very useful when you’re trying to plan enhancements, particularly if you’re performing PRK because you may have a patient who has a highly unusual epithelial layer, which may be very unusually thick or very unusually thin,” Dr. Dell continues. “When you remove that epithelium, you may have a temporary refractive surprise as the epithelium grows back at normal thickness but then reverts to its previously abnormal thickness over a period of several months. The most typical scenario for this is someone who had LASIK several years ago for, let’s say, a -8 and they have a very thick uniform layer of epithelium. And then let’s say in this hypothetical situation, they undergo cataract surgery and they wind up a -1 after the cataract surgery and someone decides to perform PRK on that patient, removes their epithelium, treats the -1 and the epithelium grows back at 50 microns instead of 80 microns and the patient is a +1.5 for a year before they eventually fade back down toward maybe +0.5. So that’s a pitfall that can be identified with epithelial mapping before that process even begins.”

Dr. Kligman says he’ll use epithelial mapping to confirm any suspicions he had about the health of the epithelium. “I’ve had patients referred to me for keratoconus evaluation who were told they weren’t candidates for LASIK and it’s happened where the topography and pachymetry didn’t match up,” he says. “It’s important to stain the ocular surface with fluorescein, and for one patient in particular it led me down the path that it could potentially be corneal limbal stem cell deficiency from contact lens overwear, and that’s a patient I would take for corneal OCT with epithelial mapping. I could then see that the epithelium was very thickened in that area and it proved the patient didn’t have keratoconus, but in fact had an unhealthy ocular surface from abusing their contact lenses.” Dr. Kilgman says he treated this patient’s corneal surface for about a year and then successfully performed PRK.

Making the Decision

After considering all of the diagnostic and clinical results, refractive surgeons must then determine the best procedure for each individual patient. This can often include delivering disappointing news.

“I think that trying to present the patient with a menu of possible refractive surgery choices and then telling them to pick which one they want is sort of a fool’s errand,” says Dr. Dell. “The best way to proceed is to identify what you believe is the best procedure for the patient and then tell them that that’s what your recommendation is. There are patients who fall into the gray area where they might be a laser vision correction candidate, but they might also be a refractive lens exchange candidate. And in that case, you need to present both options in a coherent fashion with the understanding that this is procedure A and it can correct this list of problems and this is procedure B and it can correct this different list of problems.”

Based on the photos, Dr. Khandelwal says she’ll already have an idea in her mind of what direction to discuss with a patient. “If they’re a really high myope and they have corneas that aren’t as thick, I’m going to have a very different discussion with them, as opposed if they’re a mild or moderate myope with adequate corneal thickness,” she says. “Sometimes I’ve already decided that they’re not going to be a great candidate for LASIK because their visual stromal bed is bad and the cornea that will be left is going to be too thin, in which case I’m maybe having a totally different discussion and perhaps suggesting a phakic intraocular lens such as the EVO, or maybe PRK.”

Dr. Kligman is a proponent of visual aids for patients. “I like to look at the images with my patients and explain what we’re looking at, and I have models in my exam rooms because there’s a lot of confusion among the public about the anatomy of the eye, so I always use a visual aid to point out what the cornea is and what LASIK or PRK is doing,” he says. “The color scale is a good way for them to understand astigmatism and if it’s a normal bow tie we can absolutely treat that and it’s very safe, but if you see these orange or red colors all on one side of the cornea and not on the other side, it could point to a potential risk for a bad outcome.”

Most refractive surgeons agree LASIK requires a more perfect topography than PRK.

“Generally speaking, refractive surgeons are more tolerant of slight imperfections in the corneal topography for PRK than we are for LASIK,” says Dr. Dell. “A patient’s cornea basically has to look very, very normal to perform LASIK, whereas there are some patients who have slight topographic abnormalities that might shift us toward PRK. Other factors that might shift us toward PRK would involve a propensity toward more dryness issues and also the overall corneal thickness and how much tissue will be left behind after the procedure.”

Ocular surface issues may steer surgeons away from both LASIK and PRK, says Dr. Khandelwal. “LASIK gets its reputation with dry eye because you’re cutting a flap and then you’re doing an ablation, but PRK can create dry eye as well because it’s an ablative procedure on the cornea and therefore patients can get dry eye with that,” she says. “If a patient has a tough ocular surface, they’re probably just not a candidate for either LASIK or PRK and we may talk about an intraocular lens, such as the EVO, or we’ll be talking about no surgery because sometimes the correct answer for somebody is actually not to do a procedure and focus on other treatment options, such as changing their contact lens type, getting them out of contact lenses and putting them in a scleral lens, for example. Unfortunately, some patients just aren’t candidates for any procedure.”

Often, refractive surgeons will want to counsel patients about re-evaluating their options after a few months of treatment. “Eyes that have early or more advanced keratoconus, typically the steeper area would have thinner epithelium overlying that area. If the epithelium in that area is actually thicker, usually it’s from contact lens overwear irritation and we can focus the next part of the conversation on better contact lens habits,” says Dr. Kligman.

“If they’re really motivated, then you should recommend they stay out of contacts for now, treat any ocular surface disease or dryness and re-evaluate in a couple of months to see if that surface is improving and becoming more regular and more appropriate for LASIK or PRK,” he continues. “If they don’t necessarily have any of the irregular curvature but might be on the thinner side or have a very high prescription, then I would be pushing the conversation more towards PRK. I tend to be on the more conservative side. For me, usually anything over 6 D of myopia and usually even with an average cornea, I’ll lean towards PRK. It just seems safer and we’re not pushing the boundaries of LASIK safety when it comes to the PTA (percent tissue altered).”

Dr. Dell says there has been some success in cross-linking for patients with keratoconus. “There are patients who come in seeking refractive surgery who have either indications of forme fruste keratoconus or outright keratoconus, and those patients are shifted toward corneal collagen cross-linking,” he says. “We’ve successfully treated some patients with FFKC or even outright keratoconus with cross-linking and then observed them over a period of time and then very cautiously performed PRK on them in an off-label capacity. This has to be done very cautiously and with the understanding that this is an experimental and not FDA-approved method of using lasers.”

As mentioned earlier, it’s common for patients to assume they’ll be getting LASIK since they had a friend or family member get it, not realizing there are other options. “I really lay out the pluses and minuses of both LASIK and PRK, even if they do qualify for LASIK, just so that they’re fully informed and understand what each procedure means and what healing is involved for each and I can always point to the fact that ‘Yes, it might take longer to get there with PRK, but ultimately, all of the literature shows that the results of PRK are equivalent to LASIK in the long term.’ And so, I can kind of soften the blow if I don’t think that they qualify for LASIK,” Dr. Kligman says.

Ideal candidates for LVC are younger, in their 20s, who can have long-lasting results until their 40s when they may need reading glasses, says Dr. Kligman. “Especially someone in the -4 or -5 range who really cannot see much at all without their glasses or contacts, they seem to get the biggest bang for their buck. However, we do have a good number of people in their 60s and sometimes in their 70s who are interested in LASIK. In that case, if there’s an early cataract, I don’t like to encourage LASIK just because of the much shorter duration of the effect and especially for people who are hyperopic and don’t qualify for medically necessary cataract yet, they are fantastic candidates for clear lens exchange. So that’s a good way to steer the conversation for someone who might otherwise be disappointed that they can’t get LASIK.”

Dr. Doane does very few LASIK procedures, instead leaning on the benefits of SMILE. “I do very little LASIK at this point because almost everybody is a candidate for SMILE,” Dr. Doane says. “If someone is a candidate for LASIK, they may very well be a candidate for SMILE. Situations in which they wouldn’t be candidates is if we can’t enter that prescription into the laser. Right now in the U.S. the maximum amount of astigmatism we can treat with SMILE is 3 D. Anybody above 3 D of astigmatism is going to get LASIK. And, obviously right now with SMILE, we’re just treating simple myopia. In my practice, the people who end up getting LASIK would be anybody with mixed astigmatism, anybody with higher amounts of astigmatism. The reason we end up doing SMILE is our enhancement rate is about one-third of what it is with LASIK. Not that we have huge numbers of LASIK enhancements, we just have a lower enhancement rate with SMILE than we do with LASIK.”

During the decision-making process, refractive surgeons need to keep the golden rule in mind, continues Dr. Doane. “I would only do unto a patient that which I would do to myself or a family member,” he says. “If I see things that set off red flags to avoid lamellar surgery, such as abnormal corneal anatomy, abnormalities in the epithelial thickness or shows signs of FFKC, then I am going to tell my patients I’m not doing it, and their alternatives are PRK, ICL or nothing.”

Dr. Kligman thinks similarly. “If they were my sibling or my best friend, I’d want the safest procedure for them while being equally effective one way or the other,” he says. “Of course I would prefer to do LASIK for the patient and for myself when it comes to chair time and the rapidity of healing, but I’m not going to do anything that I wouldn’t do to a family member.”

Dr. Dell is a consultant to Allergan, Bausch + Lomb, Johnson & Johnson, Lumenis, Optical Express and RxSight. Dr. Doane is a consultant to Zeiss. Dr. Khandelwal is a consultant for Alcon, Bausch + Lomb, Johnson & Johnson and Zeiss. Dr. Kligman receives research support from and is a consultant for Dompe Therapeutics and receives research support from Aerie Pharmaceuticals.

1. Belin MW, Kundu G, Shetty N, Gupta K, Mullick R, Thakur P. ABCD: A new classification for keratoconus. Indian J Ophthalmol 2020;68:12:2831-2834.