Elevated intraocular pressure is usually considered the only modifiable risk factor for glaucoma, but particularly for normal-tension disease, where progression may continue despite pressures in the normal to low range, there may be systemic pathogenic factors at play, some of which are potentially modifiable. Here, I’ll discuss several of those less commonly considered systemic factors and what recommendations we can offer to our patients.

Vascular Hypothesis & NTG

The vascular hypothesis of glaucomatous optic neuropathy is relatively well established in normal-tension glaucoma. Diminished perfusion of the optic nerve by the peripapillary microcirculation leads to retinal ganglion cell stress and ultimately cell death and atrophy. However, many risk factors are controversial with respect to their effect on glaucomatous damage, and others haven’t been thoroughly studied.

A large retrospective case control study published in the Journal of Glaucoma in 2022 reported that among patients seen at the Mayo Clinic (n=277 NTG patients; n=277 controls), multiple vascular-associated conditions were found with a higher frequency in normal-tension patients when compared to controls.1 Though diabetes, dyslipidemia, high cholesterol and coronary artery disease were found to be positively associated with normal-tension glaucoma in this study, other studies haven’t found the same associations.

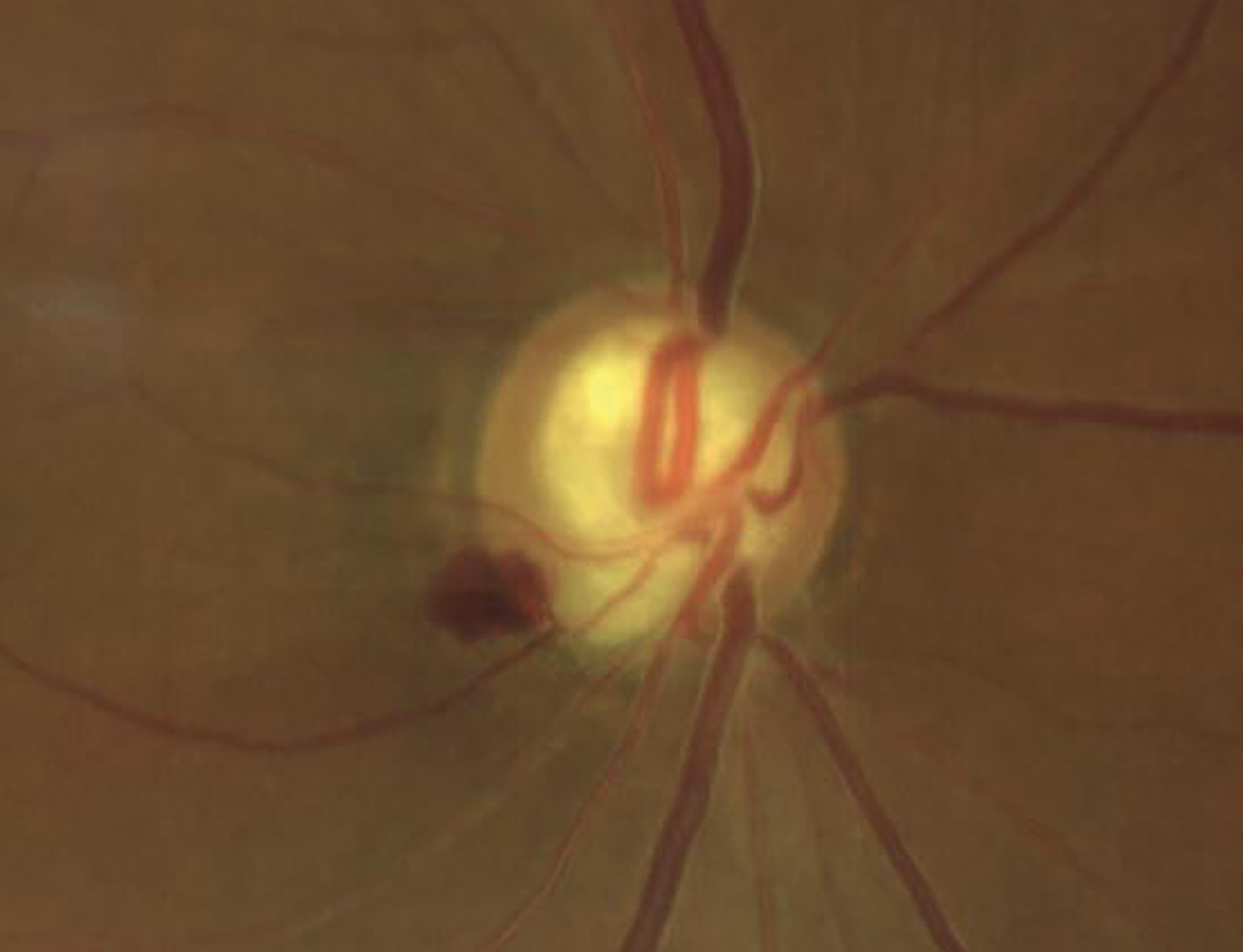

|

| Researchers at the Mayo Clinic identified two different phenotypes of normal-tension glaucoma patients. Phenotype 1 included patients with risk factors for metabolic syndrome, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease, while phenotype 2 included patients with Raynaud's syndrome, migraine headaches, anemia or systemic hypotension. (Courtesy Victoria M. Addis, MD) |

The authors of this study further classified patients with normal-tension disease into two separate groups. Phenotype 1 was defined as patients with risk factors that are associated with metabolic syndrome, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease and obstructive sleep apnea. Phenotype 2 was defined as patients with Raynaud’s syndrome, migraine headaches, anemia or systemic hypotension.

In the study, the phenotype-2 patients were more likely to be female, younger, have a lower body mass index and lower intraocular pressure. The association of phenotype 2 patients with disturbed autoregulation and higher risk of normal-tension glaucoma has been described previously.

History-taking

The diagnostic evaluation of normal-tension glaucoma should always begin with a thorough medical history and review of systems. It’s not uncommon for patients with normal-tension disease to communicate a history of cold extremities, migraine headaches, systemic hypotension or other signs of vascular dysregulation. A complete history may also be helpful in alerting the clinician to the possibility of non-glaucomatous causes of optic neuropathy, such as prior ocular trauma or other CNS pathology.

|

| Nocturnal hypotension or blood pressure fluctuations can contribute to optic nerve head ischemia and glaucoma progression. Taking antihypertensive medications in the morning instead of before bed is now recommended for glaucoma patients, based on a study that found no difference in adverse cardiovascular events associated with morning or evening dosing. |

Blood Pressure Treatment

The definition of high blood pressure has changed over time, and patients are now often treated more aggressively. However, many studies have demonstrated a correlation between both arterial hypertension and hypotension and glaucoma. Most experts believe that the treatment of hypertension is the culprit behind subsequent normal-tension glaucoma and optic nerve ischemic damage.

Exaggerated nocturnal hypotension or dips in blood pressure at night, which may compromise susceptible capillary beds, has been implicated in optic nerve head ischemia and glaucoma progression in the setting of well-controlled intraocular pressure. I routinely ask my patients to check their blood pressure at night and notify me and their primary care physician if it’s very low.

A study of treated normal-tension glaucoma patients followed longitudinally by 48-hour blood pressure monitoring demonstrated that the duration and magnitude of the nocturnal systemic hypotension, particularly when the nocturnal mean arterial pressure was 10 mmHg lower than the daytime mean arterial pressure, were risk factors for visual field deterioration in normal-tension patients.2

In a 2015 study looking at morning versus evening dosing of the blood pressure medication valsartan, equivalent 24-hour blood pressure efficacy for once-daily dosing of valsartan 320 mg was found regardless of dosing time.3

More recently in 2022, a prospective, randomized trial performed in the United Kingdom looked at the association of morning versus evening dosing of antihypertensive medication and associated cardiovascular events, and found no difference.4 Traditionally, patients have been advised to take their antihypertensive medication at night because it was thought that if patients took the medication in the morning, they were more likely to have adverse cardiovascular events. These study results have essentially contradicted this recommendation, and the authors of the study concluded that patients can be advised to take their regular antihypertensive medications at a convenient time that also minimizes potential undesirable effects.

Systemic Medications

Systemic medications used to treat conditions that affect tissue perfusion have historically led to confusion in the literature. Multiple studies have shown that calcium channel blockers may have a protective effect in normal-tension glaucoma with regard to slowing visual field progression, potentially by reducing vascular resistance via reducing the effect of endothelin-1 in ocular circulation. Some studies have shown a negative effect with primary open-angle glaucoma. Conversely, systemic beta blockers, such as Metoprolol, have been associated with a higher frequency of disc hemorrhages as well as progression in normal-tension patients. The same effects haven’t been found in primary open-angle glaucoma. The use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in the setting of normal-tension glaucoma is less well studied. Some studies suggest a protective role while others found no association.

To summarize:

1. Consider 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to look for a nocturnal dip in blood pressure in patients with continued optic nerve damage despite lower intraocular pressure. A >20-percent change from baseline is considered a large dip.

2. Involve the patient’s PCP or cardiologist to fine-tune blood pressure control in this subset of patients. It may be necessary to reduce antihypertensive medication given at bedtime.

3. Consider calcium channel blockers over beta blockers in this population as well because they may actually slow progression. While glaucoma specialists aren’t typically the ones to start patients on blood pressure medications, we can work collaboratively with a patient’s PCP. Given that normal-tension glaucoma patients tend to be symptomatic earlier than those with primary open angle glaucoma, we want to treat these patients aggressively.

Vasospasm

Blood perfusion to the optic disc is affected by the integrity of the autoregulatory system, and in the presence of vasospasm this is impaired. Vasospasm renders the eye more sensitive to both IOP-increase and blood pressure decrease. Vasospastic syndrome, a heterogeneous condition that leads to microvascular dysregulation, is now an established major risk factor for glaucoma.

Endothelin-1 is a potent vasoconstrictor peptide that’s produced by endothelial cells. Compared with healthy controls, higher plasma endothelin-1 levels have been observed in glaucoma patients, particularly in those with normal-tension glaucoma. Vasospasm may affect patients with this disease and may be an underlying culprit.

Flammer Syndrome

Primary vascular dysregulation syndrome, or Flammer syndrome, describes a complex of clinical features caused mainly by dysregulation of the blood supply.5 The range of symptoms in this syndrome is wide and can range from cold extremities to low blood pressure to reduced thirst and increased pain sensitivity. However, not all patients will ultimately develop all of these symptoms or even the disease in particular. A comprehensive questionnaire has been developed to better screen patients for this syndrome. Flammer syndrome is believed to increase the risk for certain eye diseases including normal-tension glaucoma, particularly in younger patients.

Treatment of Flammer syndrome6 consists of lifestyle modifications, such as avoidance of cold, stress and extreme exercise; nutritional recommendations, such as increasing consumption of antioxidants, taking magnesium supplements to potentially inhibit the effects of endothelin-1, increasing nighttime salt intake in the case of extreme hypotension; and medical therapy, which interestingly also includes the use of calcium channel blockers.

Silent Cerebral Infarcts

Silent cerebral infarcts are brain infarcts resulting from vascular occlusion that are found incidentally by MRI or CT in the absence of clinically detectable focal neurological signs in otherwise healthy people or during autopsy. They’re a relatively common finding, seen in one of four patients over the age of 80. A silent cerebral infarct is also a risk factor for further stroke.

Multiple studies have found evidence of frequent vascular insults in patients with normal-tension disease, and it’s been suggested that prevention of these silent cerebral infarcts may ultimately slow visual field progression. The American Heart Association recommends following stroke prevention guidelines in this subset of patients, including treating a patient’s underlying medical conditions and encouraging a Mediterranean diet, reducing sodium and avoiding smoking. The same recommendations can ultimately be made to our normal-tension glaucoma patients who show evidence of progression.

Neurodegeneration

Some recent research suggests an association between normal-tension glaucoma and dementia, while evidence for this association is mixed with primary open-angle glaucoma. The association between normal-tension disease and both OPTN and TBK1, two genes that have been implicated in frontotemporal dementia, suggest the possibility of shared neurodegenerative pathways in these two diseases.

In a recent case-control, cross-sectional cognitive screening study involving 290 glaucoma participants with normal-tension glaucoma and high-tension glaucoma controls, sampled from the Australian and New Zealand Registry of Advanced Glaucoma, the authors found that cognitive impairment assessed using the Telephone Version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment was more prevalent in the normal-tension cohort than the high-tension cohort.7 Though a linear trend was also observed between lower absolute test scores in the normal-tension glaucoma cohort, when compared with the high-tension cohort, this association wasn’t found to be statistically significant. More research in this area is necessary.

Neuroimaging

When is neuroimaging indicated in patients with normal-tension glaucoma? Though studies have shown that routine neuro-imaging for normal tension glaucoma has a low sensitivity for detecting mass lesions, there are certain factors that should prompt consideration for neuroimaging, such as:

• age younger than 50 years;

• visual acuity less than 20/40;

• vertically aligned field defects, which aren’t classic for glaucoma;

• optic nerve pallor in excess of cupping;

• loss of color vision (red desaturation);

• unilateral disease; and

• rapidly progressive disease despite well-controlled IOP.

In these cases, referral to a neuro-ophthalmologist who can assist in helping to rule out other non-glaucomatous causes for progressing disease may be helpful. Normal-tension glaucoma is a diagnosis of exclusion, so when a patient’s pressures are great but they’re still progressing, it’s important to ask yourself, “Is this really glaucoma?” to ensure you have ruled out other causes for a patient’s vision loss.

In summary, all patients should be encouraged to maintain a heart-healthy diet and lifestyle.

Exercise, weight loss (if overweight), and smoking cessation should be stressed, as should a diet rich in antioxidants. Collaborate with a patient’s PCP or cardiologist if necessary, and always remember to take a thorough review of systems as many patients with normal-tension disease suffer from a host of other conditions. Finally, if the diagnosis of NTG is unclear, consider neuroimaging and referral to a neuro-ophthalmologist.

Dr. Addis is an assistant professor of clinical ophthalmology at the Scheie Eye Institute, University of Pennsylvania. She has no related financial disclosures.

Dr. Singh is a professor of ophthalmology and chief of the Glaucoma Division at Stanford University School of Medicine. He is a consultant to Alcon, Allergan, Santen, Sight Sciences, Glaukos and Ivantis. Dr. Netland is Vernah Scott Moyston Professor and Chair at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

1. Funk RO, Hodge DO, Kohli D, Roddy GW. Multiple systemic vascular risk factors are associated with low-tension glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2022;31:1:15-22.

2. Charlson ME, de Moraes CG, Link A, Wells MT, Harmon G, Peterson JC, Ritch R, Liebmann JM. Nocturnal systemic hypotension increases the risk of glaucoma progression. Ophthalmology 2014;121:10:2004-12.

3. Zappe DH, Crikelair N, Kandra A, Palatini P. Time of administration important? Morning versus evening dosing of valsartan. J Hypertens 2015;33:2:385-392.

4. Mackenzie IS, Rogers A, Poulter NR, Williams B, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes in adults with hypertension with evening versus morning dosing of usual antihypertensives in the UK (TIME study): A prospective, randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint clinical trial. Lancet 2022;400:10361:1417-1425.

5. Flammer, J., Konieczka, K. The discovery of the Flammer syndrome: A historical and personal perspective. EPMA Journal 2017;8:75–97.

6. Konieczka K, Flammer J. Treatment of glaucoma patients with Flammer syndrome. J Clin Med 2021;10:18:4227.

7. Mullany S, Xiao L, Qassim A, Marshall H, Gharahkhani P, MacGregor S, Hassall MM, Siggs OM, Souzeau E, Craig JE. Normal-tension glaucoma is associated with cognitive impairment. Br J Ophthalmol 2022;106:7:952-956.