|

Problems with traditional cap plugs, including extrusion and rubbing of the cap on the eye have lead to the use of intracanalicular plugs. These plugs are synthetic plugs placed below the surface of the eyelid to prevent rubbing on the eye. The SMARTPlug (Medennium Inc., Irvine, Calif.) is an intracanalicular plug that is thermosensitive, expanding and hardening into the canaliculus with body heat. Recent reports of SMARTPlug infections have surfaced, in conjunction with a prevalence of infected SMARTPlugs in our practice. With that in mind, we conducted a retrospective study to evaluate patients who presented to our practice with canaliculitis who previously had intracanalicular SMARTPlugs inserted.

|

Study Results

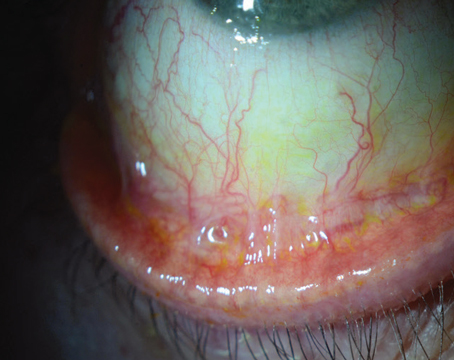

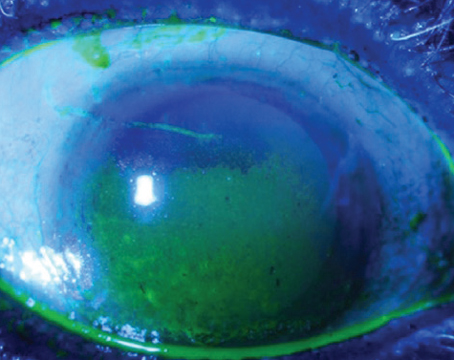

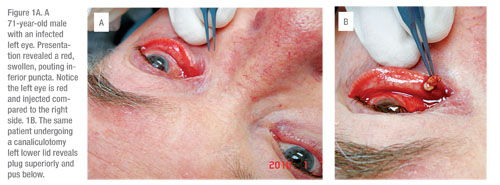

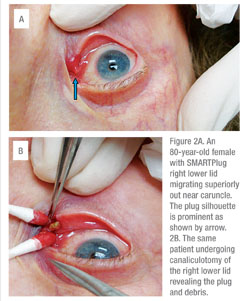

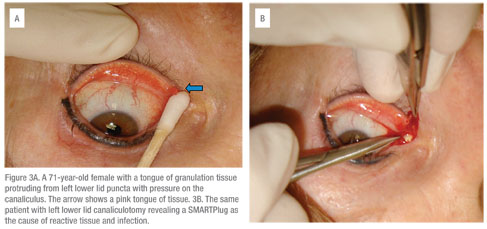

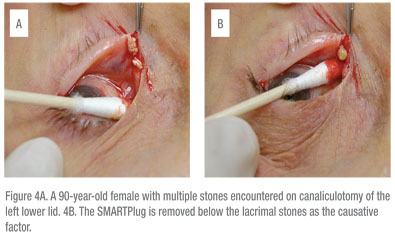

A total of 1,026 patients received SMARTPlugs in our practice from 2002 to 2009, with a total of 1,845 plugs. Seventy-four percent of the patients were female and the average age of all patients was 71-years-old. A total of 61 surgeries were performed by one surgeon (JPF) for SMARTPlug-induced canaliculitis representing a 6-percent canaliculitis rate. The average time to develop canaliculitis after SMARTPlug insertion was 2.7 years. The left lower lid was the most common site, followed by the right lower, right upper and left upper lids. Canaliculitis presented typically as a swollen, red, pouting puncta with pus and chronic conjunctivitis. Canaliculotomy usually revealed a dilated canaliculus with stones, pus and the plug. An embedded plug and granulation tissue were also observed frequently.

|

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest series of recorded canaliculitis caused by SMARTPlugs. Canaliculitis in the absence of punctal plugs is a well-described condition, usually presenting as a red, pouting puncta, causing conjunctivitis in the affected eye. One study confirmed primary canaliculitis is more prevalent in women around the age of 70, with Actinomyces israelii as a common isolated organism.1 Contrary to this, a recent series reported Streptococcus and Staphylococcus as the most common pathogens, leading to the conclusion that Actinomyces may not be as prevalent a causative organism.2

|

(Editor’s note: Repeated attempts to solicit comment from the manufacturer were unsuccessful.)

Dr. Fezza and Dr. Gindoff practice at the Center for Sight, 2601 South Tamiami Trail, Sarasota, Fla., 34229. They have no financial interest in this product.

1. Repp DJ, Burkat CN, Lucarelli MJ. Lacrimal Excretory System Concretions: Canalicular and lacrimal sac. Ophthalmology 2009;116; 2230-5.

2. Zaldivar RA, Bradley EA. Primary Canaliculitis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;25:481-4.

3. Fender RS, Rao RR, Lissner GS, et al. Atypical mycobacterial keratitis and canaliculitis in a patient with an indwelling SMARTPlug. Br J Ophthalmol 2010 Mar;94(3): 383-4.

4. Fowler AM, Dutton JJ, Fowler WC, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae canaliculitis associated with SMARTPlug use. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;3:241-3.

5. Hill RH, Norton SW, Bersani TA. Prevalence of canaliculitis requiring removal of SMARTPlugs. Ophthalm Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;25:437-9.