Clinicians say the problem with managing corneal ulcers is the famous quote regarding medical diagnoses, “When you hear hoofbeats behind you, think horses, not zebras,” doesn’t always apply: A fungal “zebra”—though infrequent—is still a possibility. Because of this, corneal specialists have developed systematized methods for diagnosing and treating these infections. Here, experts outline their approaches to help you tackle these cases more effectively.

Diagnosis

In the United States, the most common cause of corneal ulcers is bacteria. “In some hot and humid countries like India or Singapore, fungal ulcers might be more common than bacterial ulcers. Similarly, hot and humid areas of the United States, such as Miami and Houston, may have a lot of fungal infections, but, in general, in the United States, the cause is primarily bacteria,” says Francis Mah, MD, who is in practice in La Jolla, California.

If a patient presents with a corneal ulcer, Laguna Hills, California’s John A. Hovanesian, MD, says the degree of the patient’s discomfort sometimes is a clue. “Bacterial ulcers tend to be more painful and more acute, while herpes simplex ulcers are less so,” he says. “With some rare organisms, like Acanthamoeba, the pain is classically described as much worse than you would expect by looking at the eye, because it affects the corneal nerves. History and appearance can also provide insights. For example, a very densely infiltrated ulcer with a lot of white blood cells in the cornea hints at a bacterial or fungal cause, so you would direct your thinking that way.”

According to Dr. Mah, culturing is a delicate topic as far as recommendations or standard of care. “In general, if you go across the country and talk about corneal ulcers, the majority of corneal ulcers don’t need to be cultured and probably aren’t,” he says. “Most ulcers are probably 1 mm, definitely smaller than 2 mm, and are probably associated with contact lens wear. Some of them are probably sterile. I would say, in general, 75 percent to 90 percent of corneal ulcers are probably not being cultured, and I think it’s probably appropriate, if you include those types of corneal ulcers.”

Dr. Mah is co-chair of the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Preferred Practice Patterns on corneas, and the PPP for bacterial keratitis1 recommends that the following types of ulcers need to be cultured: those larger than 2 mm; those in the central cornea or the central visual axis; those that cause some stromal melting; those that are atypical looking; and those that are chronic and aren’t responding to treatment. “Those should definitely be cultured. Are you wrong to culture all ulcers? No. You’re definitely not wrong in culturing small, non-melting ulcers, but you’re also not wrong in not culturing them,” Dr. Mah explains.

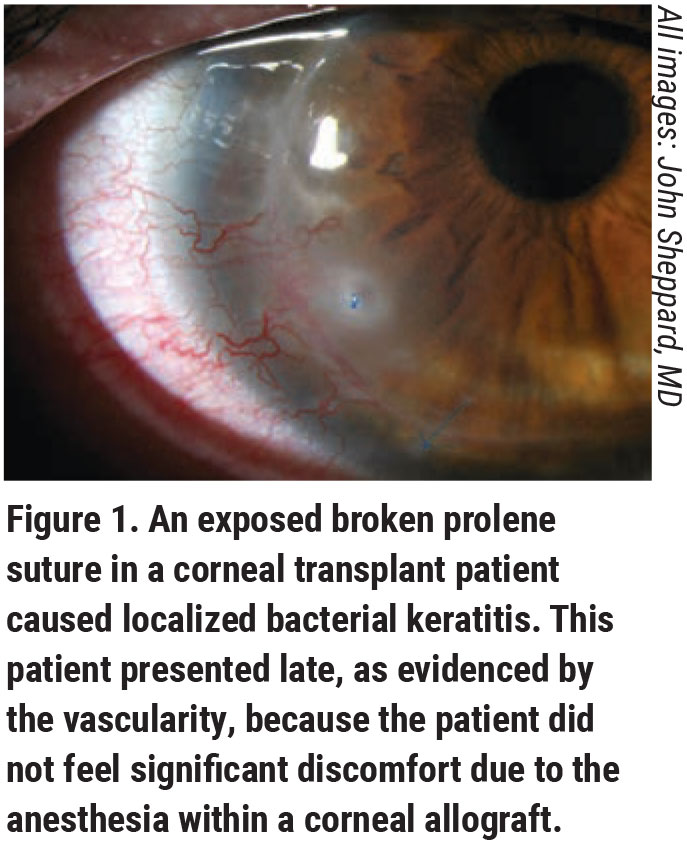

Corneal specialist John Sheppard, who practices in Norfolk, Virginia, notes that ophthalmologists need to be prepared to obtain a wide variety of cultures, if needed. “Since the most common etiology of keratitis by far in the United States is bacteria, we have several varieties of bacteria culture media available,” he says. “If a patient has an epithelial defect or is at high risk of infection, we’ll do a proactive sweep of the conjunctival cul-de-sac to assess the presence of pathogenic flora in the event that a problem arises and then place the patient on empirical preventive therapy. The acute, obviously infected eye, on the other hand, requires, if at all possible, a high-yield direct culture of the actual ulcer. This is done with preservative-free topical tetracaine and a Kimura spatula, which is sterile. I apply it directly onto a bacterial agar culture plate.

“Compared to other cultures obtained in the human body, the titer of organisms in the eye is log orders lower, so it’s often difficult to isolate organisms with standard media, such as a cotton swab,” he adds. “Furthermore, cotton is bacteriostatic, so we recommend calcium alginate or synthetic fiber swabs. The direct inoculation on the bacteria media gives you the highest yield. We also generally screen for fungus, which is a different type of media. We do the bacterial culture first because the fungal media contains antibacterials to allow the fungus to grow. Finally, we’ll obtain a slide for gram stain.”

Next, clinicians discuss the nuances of treating the four major causes of infectious corneal ulcers: bacteria; viruses; fungi; and parasites.

Caused by Bacteria

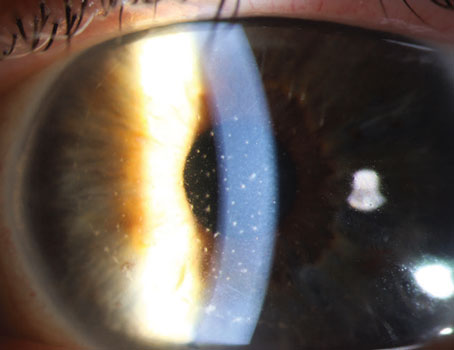

|

According to Dr. Mah, ulcers that are typical and don’t require culturing are usually treated using a topical fluoroquinolone antibiotic. Only three of these drugs are FDA-approved for treating bacterial corneal ulcers: ofloxacin; ciprofloxacin; and levofloxacin 1.5%. Of those, only ofloxacin and ciprofloxacin are commercially available. “Others, like gatifloxacin, moxifloxacin and besifloxacin, haven’t undergone trials for FDA approval [for the treatment of ulcers],” Dr. Mah explains. “In general, they’re more potent, and there have been independent studies to show that they’re effective. Their patterns of resistance and susceptibility are probably better than ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin, so even though ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin are FDA-approved, and gati, moxi and besi aren’t, I don’t think you can go wrong in your treatment choice. I think it’s probably preferred to use moxifloxacin, gatifloxacin or besifloxacin as a first line. If you still have samples of besifloxacin, you can grab them off the shelf and get those antibiotics started.”

More severe bacterial ulcers require treatment with compounded or fortified antibiotics. “The most typical fortified antibiotics used for bacterial corneal ulcers are vancomycin (25 mg/mL or 50 mg/mL) and then tobramycin (14 mg/mL),” Dr. Mah adds.

However, fortified antibiotics aren’t always immediately available. “So, we start with what’s locally available and then switch when the compounded antibiotics become available,” Dr. Hovanesian explains. “Typically, the first thing that improves in bacterial ulcers is the symptom of pain, and the last thing that improves is the vision. Somewhere in between, we begin to see improvement in the appearance of the ulcer.”

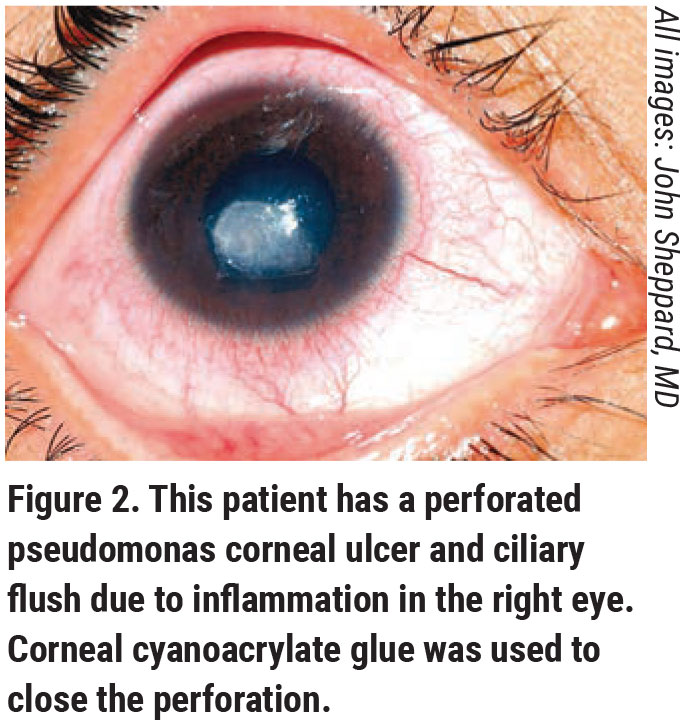

He also cautions that some bacterial ulcers actually look a little worse before they start to look better, particularly organisms like pseudomonas. “If you’re catching the ulcer on the upswing of the organism’s growth, you may effectively treat it with antibiotics, and it may actually look a little worse on the cornea for a day or two before it starts to turn around,” Dr. Hovanesian says. “We normally will see improvement in pain for patients within 24 hours of initiating appropriate therapy. This brings up the issue of compliance, which is important.”

Compliance can be challenging from the initiation of treatment. “We typically start these antibiotics in bacterial ulcers every five to 10 minutes for the first couple of hours to give a loading dose to the eye,” Dr. Hovanesian explains. “We then use them hourly around the clock for the next day or so. That’s difficult for patients. If patients don’t take the condition seriously, or even if they do take it seriously but are just distracted, they fail. During counseling, it’s important to talk about the serious nature of ulcers. We used to admit patients to the hospital for corneal ulcers if we had doubts about their ability to use their drops. We don’t do that so much anymore, but educating patients helps them understand that these little eye drops are not just to relieve their pain. They’re being used to prevent vision loss and to stop a process that will cause permanent damage. Helping patients become mentally invested in the treatment is important to get them compliant.”

In some cases, patients may need to be referred to a corneal specialist. “It’s important to have second opinions available, so it’s imperative to have a referral relationship with local cornea specialists. It’s good to set that up before you have an eye with a light spot staring at you in your slit lamp,” Dr. Hovanesian adds.

Viral Ulcers

According to Dr. Hovanesian, viruses, such as herpes simplex, are the second most common cause of corneal ulcers, after bacteria. While there’s no cure for herpes, and the virus can reactivate, current treatments include topical or oral antivirals.

Most commonly, a patient will present with a change in vision, rather than pain or discomfort. Many times, there will be a previous history of herpes keratitis. The diagnosis is typically made based on the patient’s history, and the classic appearance of a dendrite. Cultures are rarely needed, due to the classic appearance.

According to Dr. Mah, treatment for epithelial herpes keratitis is debridement with a Kimura spatula, or even a Q-tip, to debulk the virus; or oral antivirals such as acyclovir or valacyclovir, or topical ones such as ganciclovir gel. “Although trifluridine is also FDA-approved, it’s extremely toxic so it probably shouldn’t be used since we have much better and less toxic agents,” he adds.

Fungal Ulcers

Dr. Mah explains that, if the etiology of an ulcer is trauma from vegetable matter, it’s time to start thinking about fungi. These ulcers can have satellite or branching lesions, and tend to go deep instead of wide on the cornea as bacterial ulcers do, physicians say. “As far as the treatment, I usually culture them first and get some identification of the fungus,” Dr. Mah says, “because the anti-fungal agents are usually a lot more toxic, and there’s only one that’s FDA-approved, so the majority of them have to be compounded. In general, the agents that we use for fungal keratitis are natamycin, which is FDA-approved for fungal keratitis in the United States. Amphotericin B and voriconazole can be used, but they need to be compounded.”

The Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial (MUTT), a Phase III, double-masked, multicenter trial that randomized patients to voriconazole 1% or natamycin 5%, found that natamycin was associated with significantly better clinical and microbiological outcomes than voriconazole for smear-positive filamentous fungal keratitis.2 Fungi become resistant to treatment much more commonly than bacteria, however, so Dr. Mah says that clinicians may want to consider covering with two agents instead of just one.

|

Dr. Sheppard explains that fungal ulcers are challenging because of the duration and persistence of the infection, and the necessity of early treatment. “Unfortunately, the fungal medicines are like putting battery acid in your eye, and you don’t just give antifungals empirically,” he says. “As a result, we may just kind of hedge, treat for bacteria, and give the patient an oral antifungal, which begins to protect the presumed but not immediately obvious fungal process and keeps the patient out of trouble until you have the gram stain back or a positive fungal culture. Of course, fungal cultures can take up to a week to grow, so that’s not good. As a result, whenever we suspect Acanthamoeba or a fungus, both of which are quite rare, we’re able to move forward and get patients treated with the right agent quickly by identifying the offending organism early with the confocal microscope. Skilled confocal imaging can also identify Acanthamoeba cysts in many cases. Severe infections are more common because of delayed diagnosis, or the initial therapy isn’t the right one.”

Polymicrobial infections must also be suspected. For instance, the neurotrophic chronic quiescent herpetic cornea may become secondarily infected with a fungus, which presents notoriously late in this scenario due to the occasional complete lack of corneal sensation, physicians say.

Parasitic Infections

Dr. Mah explains that Acanthamoeba as a cause for corneal ulcers is typically confused with herpes simplex virus and contact lens overwear. “Usually, these patients are started on antibiotics,” Dr. Mah says. “Because of the confusion with HSV, they can also be put on an antiviral, like acyclovir or valacyclovir. Then, if it’s persistent, and the clinician really thinks it’s HSV, sometimes the patient will be put on steroid drops, which is the wrong thing to do for Acanthamoeba.”

All treatments for Acanthamoeba need to be compounded. “You want to start with a biguanide,” Dr. Mah explains. “The classic ones used in ophthalmology are polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) and chlorhexidine. So, we want to start with at least one, if not both, of those. You can also use other agents. Brolene, for example, is available in Europe. If you can get it, it works well. Propamidine is another one used in the United States. It’s an antiviral, but it has efficacy against Acanthamoeba. Neomycin can also be used, but it’s unfortunately associated with a lot of allergy and toxicity. The best ones that we know of right now are PHMB and chlorhexidine. In general, Acanthamoeba is an entity that you definitely want to culture and identify because, once you identify it, you’ve kind of committed to weeks or months of therapy. Again, these agents are relatively toxic, and they’re compounded, so you can’t just go down to CVS and order them.”

Dr. Mah has a financial interest in Alcon, Allergan, Bausch & Lomb, Novartis, and Eyevance. Drs. Hovanesian and Sheppard have no relevant financial interests to disclose.

1. https://www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/bacterial-keratitis-ppp-2018

2. Prajna NV, Krishnan T, Mascarenhas J, et al, for the Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial Group. The Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial: A randomized trial comparing natamycin vs voriconazole. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013:131:4:422-429.