Primary epiretinal membrane is common, with a prevalence of 4 to 18.5 percent, and it commonly occurs together with cataracts.1 In patients with both conditions, surgeons say, setting realistic expectations and deciding which procedure to perform first can improve outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Role of OCT

According to Vance Thompson, MD, who is in practice in Sioux Falls, SD, it’s important to perform optical coherence tomography on every routine cataract surgery patient. “This is mainly because we’re trying to avoid any disappointing visual surprise. We also do a full dilated retinal evaluation and examine the macula very closely. Sometimes, we have a patient who has an epiretinal membrane that can be seen on OCT, but is not seen on physical exam. Or, you may see something subretinal that you don’t see on your exam,” he says.

Nick Mamalis, MD, professor of ophthalmology at the University of Utah’s John Moran Eye Center, agrees. “Sometimes, especially with moderately dense cataracts, we just don’t get a great view, and a very subtle epiretinal membrane can sometimes be missed preoperatively,” he says. “You don’t want to dilate a patient two weeks postoperatively and see an epiretinal membrane. You really want to know that ahead of time, and I think a good macular OCT is the best way to do that.”

Single or Combined Procedure?

When a cataract patient presents with an epiretinal membrane, surgeons will need to decide whether to perform a combined surgery or perform the cataract surgery first and address the epiretinal membrane at a later time. “Even if I think it’s best to perform cataract surgery first, I will usually work with a retinal specialist, especially if it’s a pretty significant epiretinal membrane,” says Thomas Oetting, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences at the University of Iowa. “The retina specialist will talk to the patient about the process and the potential for addressing the epiretinal membrane after cataract surgery. Every now and then, the retina specialist will surprise me by saying that he or she wants the patient to undergo a combined procedure.”

|

| The Moran Eye Center’s Nick Mamalis, MD, says that if a patient has a minor cataract but significant ERM, the retina specialist should perform the membrane peel and vitrectomy before the cataract surgery is done. |

If the decision is made to do the cataract surgery as the first, standalone procedure, the surgeon will need to take the presence of an epiretinal membrane into consideration. “I always ask myself what I can do for this patient, either if they need a vitrectomy in the future or if they already have decreased contrast sensitivity,” says Dr. Oetting. “So, there are issues regarding IOL choice and the patients’ propensity to experience cystoid macular edema, because these patients are at high risk of developing the condition after surgery. We can try to prevent cystoid macular edema using prophylaxis. I always make a big deal about showing patients the OCT so that they know what it looks like before cataract surgery. No matter how much you talk about it, patients are always slightly suspicious that the cataract surgery caused the epiretinal membrane. This is one of the main reasons to get an OCT on all routine cataract surgery patients.”

Dr. Mamalis says the decision between standalone and combined procedures depends on how significant the epiretinal membrane is. “If it’s a dense epiretinal membrane and there’s a lot of distortion of the retina, or if there’s any sign of traction on the retina, then the decision would be different than if you were looking at a small epiretinal membrane with minimal distortion, no obvious traction and no obvious edema,” he says. “In the setting of a small epiretinal membrane, I think it’s all right to do the cataract surgery first. Then, if the epiretinal membrane worsens, a procedure can be done later. If there’s a relatively dense epiretinal membrane and it’s causing traction and a lot of distortion, you can perform a combined procedure with a retina colleague.”

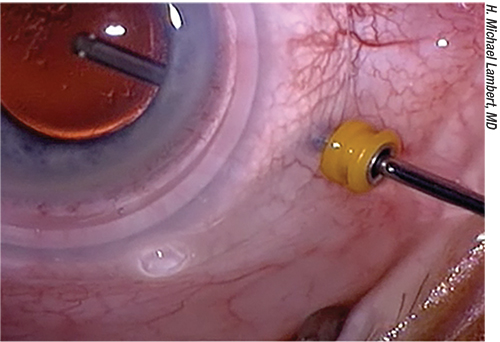

Often, with combined procedures, retina specialists like to put their ports in first when the eye is completely pressurized. “In these cases, we’ll have them put in their ports for the vitrectomy, and then put in the irrigation line and keep the pressure fairly low,” Dr. Mamalis explains. “Then, I’ll go ahead and just do my regular phacoemulsification. The only difference is that I put a single 10-0 nylon radial suture in the cataract wound. Even if it’s a 2.4-mm wound, I’ll still put a suture in there so that there’s no chance of the wound opening during the vitrectomy. The retina specialist will then proceed with the vitrectomy and the membrane peel.”

If a patient has an insignificant cataract and a very significant epiretinal membrane, Dr. Mamalis has the retina specialist perform the membrane peel with the vitrectomy first. “Retina specialists are very good at counseling patients and telling them that one of the side effects of a vitrectomy is that the cataract will get worse,” he says. “That can happen relatively quickly, and, in these cases, retina specialists will send the patient back to me for the cataract surgery when it gets bad enough to warrant surgery.”

Dr. Thompson says that he never performs a combined procedure, and he leaves it up to the retina specialist to decide which procedure should be performed first. “Most retina specialists say it’s tough to predict how visually significant a mild or sometimes even moderate epiretinal membrane can be and to truly make a balanced decision. Many times, they suggest taking out a visually significant cataract first, so that we can quantify how much the epiretinal membrane is affecting the patient’s vision. However, an epiretinal membrane is not an emergency. Time doesn’t typically affect the success of surgery. It can be helpful to have a patient make an educated decision based on his or her vision post-cataract surgery. You just don’t want a visual surprise. Patient expectations are so high with cataract surgery. If you don’t tell them ahead of time that they have an epiretinal membrane and that their vision may not be as good as they were hoping, then they think the surgery caused it. And that’s the last thing we want,” he says.

Recently, a study was conducted to assess cataract surgery outcomes in patients with epiretinal membranes.1 The study was a retrospective clinical database study that included 812 eyes with primary epiretinal membrane and 159,184 reference eyes. Compared to the reference eyes, eyes with epiretinal membrane had higher rates of cystoid macular edema and less postoperative improvement in visual acuity.

In this study, epiretinal membrane eyes assessed four to 12 weeks postoperatively gained 0.27 logMAR (approximately three Snellen lines), with 200 of 448 (44.6 percent) improving by 0.30 logMAR or more (≥3 Snellen lines) and 32 of 448 (7.1 percent) worsening by 0.30 logMAR or more. Reference eyes gained a mean of 0.44 logMAR (approximately four Snellen lines), with 48,583 of 77,408 (62.8 percent) improving by 0.30 logMAR or more and 2,125 of 77,408 (2.7 percent) worsening by 0.30 logMAR or more. Although all eyes with preoperative VA of 20/40 or less improved, only reference eyes with a preoperative VA better than 20/40 showed improvement. Cystoid macular edema developed in 57 of 663 ERM eyes (8.6 percent) and 1,731 of 125,435 reference eyes (1.38 percent). Epiretinal membrane surgery was performed in 43 of 663 epiretinal membrane eyes (6.5 percent).

Additionally, an Australian study found that combined cataract and epiretinal membrane vitrectomy is just as effective as consecutive operations for improving visual acuity, while reducing the risk of exposing a patient to two separate surgical procedures.2

This retrospective study included 209 eyes: 62 had cataract surgery prior to epiretinal membrane peel, 105 had combined epiretinal membrane peel and cataract surgery, and 28 had cataract surgery after epiretinal membrane peel. Patients who had cataract surgery before epiretinal membrane, versus combined surgery, had improvements in visual acuity at three months (-0.10 vs -0.08) and 12 months post-follow-up (-0.18 vs -0.22), with no significant difference between the groups. There was also no difference between the groups with regard to the proportion of eyes that had perioperative or postoperative complications.

IOL Choice

According to Dr. Oetting, an epiretinal membrane is a contraindication to multifocal IOLs, but not to toric IOLs. “Because you’re most likely going to do a vitrectomy, I would not implant a silicone lens,” he says. “Besides those exceptions, I think the IOL discussion is relatively simple. The cataract surgery itself is relatively straightforward. There’s really not that much different about it. I sometimes will put in a slightly larger lens, like an Alcon MA50, because it’s easier to do a vitrectomy with a bigger lens. However, I usually just use a single-piece acrylic lens.”

Postoperative Considerations

Postoperatively, it’s important to avoid cystoid macular edema. Dr. Oetting recommends using the prednisone a little longer. “Instead of doing my usual taper of q.i.d. for a week, then t.i.d. for a week, then b.i.d., then q.d. with prednisone acetate, I might go 6, 4, 3, 2, 1,” he says. “I usually give patients a week to heal postoperatively before starting an NSAID. I typically use Acular (ketorolac tromethamine, Allergan) and Pred Forte (prednisolone acetate ophthalmic suspension, Allergan), as they are inexpensive. We usually place intracameral moxifloxacin, so we do not routinely use a topical antibiotic. I use the NSAID for about a month, and then I assess the patient. If any cystoid macular edema is present, then I will continue it for longer.”

Dr. Oetting sees patients a year after cataract surgery to assess the epiretinal membrane. “We want to see how the epiretinal membrane is doing and assess whether it has gotten to the point where a retina surgeon might want to do a membrane peel,” he says. “If there is some functional decline that appears to be related to the epiretinal membrane following the cataract surgery, I think it warrants having a retina specialist look at the patient.”

Outcomes and Expectations

Dr. Oetting notes that patients with an epiretinal membrane who undergo cataract surgery generally have a good outcome, but says it’s important for patients to have realistic expectations. “Often, there’s some decline in vision that’s related to the retina and some decline in vision that’s related to the cataract, and you’re only addressing the cataract part,” he says. “Cystoid macular edema is a real issue, so you have to warn patients about that, and you have to treat for that. That can be a limiting factor for a while, but it typically lasts only for the first two or three months. Patients can usually separate the symptoms of the epiretinal membrane from the symptoms of the cataract. I explain these differences before surgery, so they can recognize that the distortion and the metamorphopsia that comes from the epiretinal membrane is not going to get much better with the cataract surgery, but the glare and the generalized blur will improve with cataract surgery. This helps patients to not be disappointed with their outcome.”

Dr. Thompson agrees. “Whenever you mention a retinal issue, patients get very concerned, because they’ve heard of things like macular degeneration. It is worth taking time to help alleviate their fears and set realistic expectations,” he says. “It’s important to make sure that they’re psychologically handling the explanation well, and that their expectations are set for surgery to maximize the chance for their success.” REVIEW

Dr. Thompson, Dr. Mamalis and Dr. Oetting report no financial interest in the specific products discussed.

1. Hardin JS, Gauldin DW, Soliman MK, Chu CJ, Yang YC, Sallam AB. Cataract surgery outcomes in eyes with primary epiretinal membrane. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136:2:148-154.

2. Ng FJ, Allen P, Vote BJ. Combined epiretinal membrane and cataract surgery: Visual outcomes. Australian Medical Student Journal. April 15, 2018. http://www.amsj.org/archives/6366