A few years ago, when a cataract surgeon was faced with an eye that had minimal or no capsular support, there were only two surgical options: insert an anterior chamber lens or suture a lens into the posterior chamber. Today, the options for posterior lens fixation have proliferated, changing the nature of that choice.

“Lack of capsular support is something we’ve always been concerned about and tried to prepare for in cataract surgery, but our options for managing this situation have increased through the years,” says Kendall E. Donaldson, MD, MS, medical director of Bascom Palmer Eye Institute’s Plantation, Florida, location and associate professor of ophthalmology and co-director of the corneal fellowship at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. “Today we see more iris-fixated posterior chamber lenses. We have glued IOLs, thanks to Amar Agarwal, MD, in India. We have the relatively new Yamane technique, which involves placing the haptic through a channel and then cauterizing the tip, which causes it to enlarge so we can tuck it into the sclera. And, we have the option of using long-lasting Gore-Tex to suture an Akreos lens in place. In the past, we would have used prolene to suture a lens to the sclera.” (She explains that although suturing with prolene is still a widely-used technique, the prolene can erode over time, often resulting in the lens dropping to the back of the eye 10 years later. In contrast, Gore-Tex doesn’t erode.)

“Today, we have options that are more cornea-friendly and angle-friendly,” agrees Nicole Fram, MD, managing partner at Advanced Vision Care in Los Angeles and a clinical instructor of ophthalmology at the Stein Eye Institute, University of California, Los Angeles. “There have been many exciting advances in scleral fixation. If you can offer someone a more physiologically appropriate procedure with the lens placed away from the cornea and iris, I think you should.”

Given the expansion of management alternatives in this situation, the question arises: Is the placement of an anterior chamber lens—with its attendant possible complications—still a viable option? Here, surgeons experienced in anterior and posterior lens placement share their experiences and opinions.

ACIOLs: A Riskier Option?

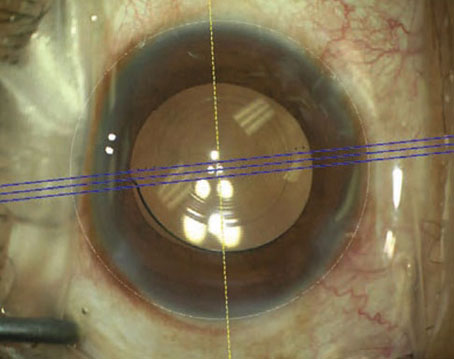

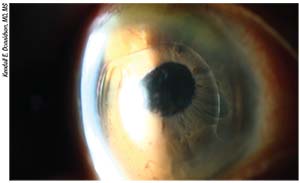

One of the most obvious reasons to question the validity of placing an anterior chamber lens is that

|

| Anterior chamber IOLs like the one above can work well, with minimal side effects, when the anterior chamber is deep and the IOL is properly sized and positioned. However, new ways of fixating posterior chamber IOLs have many surgeons favoring that alternative. |

ACIOLs sit in a place that nature didn’t intend to hold a lens. That makes this option susceptible to a list of potential complications that can result in damage to the cornea, iris or angle.

“Posterior chamber lenses are generally thought of as being healthier for the eye because they’re farther from the corneal endothelium,” says Dr. Donaldson. “They’re at a more physiologic location, behind the iris. Anterior chamber lenses sit close to the corneal endothelium, and as a result the patient will lose some endothelial cells over time. That could lead to corneal edema—or even a corneal transplant. For that reason, many surgeons think of anterior chamber IOLs as making the most sense when a patient is older. Older patients will have fewer decades for corneal issues to develop.”

Working in a tertiary referral practice, Dr. Fram often encounters those problems. “We see many complications caused by malpositioned—and even properly placed—anterior chamber IOLs,” she says. “In the vast majority of cases we see at least one of the following complications: endothelial failure with corneal edema; chronic intraocular inflammation, or uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema (UGH) syndrome; or cystoid macular edema. Sometimes we see all three. Most disappointing is when we find chronic inflammation, a decompensated cornea and mismanagement of iris defects, resulting in extensive peripheral anterior synechiae with secondary glaucoma. That limits the possibility of using more cutting-edge procedures for visual rehabilitation that would result in faster recovery, such as Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK). There’s no question that over time, a malpositioned ACIOL will eventually induce one or all of these co-morbidities.

“In contrast, I believe that if you have the patience and skill set to fixate posterior chamber IOLs, whether it’s intrascleral fixation or suture scleral fixation, and you obey the basic tenets of performing proper anterior vitrectomy or pars-plana-assisted anterior vitrectomy, you won’t have as high an incidence of complications,” she says. “Any secondary IOL-fixation technique can result in endothelial failure, chronic inflammation or CME. However, in our experience, those are far less common with fixated posterior chamber IOLs than with ACIOL placement.

“Of course,” she adds, “all of this is only true if you’re properly trained in the technique you’re using.”

Challenges Placing an ACIOL

Another concern that can exacerbate the inherent potential problems with a lens sitting close to the cornea is that anterior chamber lenses are challenging to fit. Mitchell P. Weikert, MD, associate professor at the Cullen Eye Institute at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, says he believes that anterior chamber lenses still have a place when performing surgery on a patient with weakened zonules—if they fit well. “If they fit well in the anterior chamber, they usually do very well and have very few complications,” he says. “However, proper fitting can be a challenge, for several reasons.

“For one thing, we have limited sizes available to us,” he says. “For example, Alcon offers three sizes of anterior chamber lenses; Bausch + Lomb offers two sizes. The size of everyone’s anterior chamber is a little different, so it can sometimes be challenging to find the right lens. Second, the dimensions of the anterior chamber horizontally and vertically can be a little different. Third, not every OR stocks a full array of the ACIOLs that are available. Although we may plan to use an AC-IOL in some cases, they’re more commonly used following a complication that precludes the use of a posterior chamber IOL. Unless you’ve ordered a special lens ahead of time, the OR may not have the one you need.”

Dr. Weikert also notes another problem. “These lenses fit in the angle, so we ideally need to know the angle-to-angle measurement,” he points out. “Typically we don’t have that. We can get it with ultrasound biomicroscopy or with an optical coherence tomography scan that spans the entire anterior segment, but these measurements are not typically performed preoperatively in all patients. Instead, if we’re in the OR and need to implant an ACIOL, we’ll just measure the white-to-white distance and add a millimeter. Doing that is common practice, but it’s been shown to have fairly poor correlation to the actual angle-to-angle measurement, or even the sulcus measurement.

“Fortunately,” he adds, “the lenses are forgiving; they’ll adapt a little bit to different anterior chamber sizes, although some lenses are more flexible than others. Generally, a Kelman-design lens with four-point fixation is preferable.”

Dr. Weikert also points out that you need a large, 6-mm incision to insert an anterior chamber lens. “Implanting an anterior chamber lens typically requires a scleral incision, so you have to take down conjunctiva, and you need to have enough real estate on the eye to accommodate the large incision,” he says. “Of course, you can do a corneal incision for an anterior chamber lens; many surgeons will simply enlarge their clear corneal incision to 6 mm to insert the lens if they encounter complications during cataract surgery. However, that’s when you’re at risk for creating astigmatism. Also, you’ll have to leave the sutures in for a while, so it can take a long time to heal. In contrast, sclerally fixating a smaller, foldable lens that you can fit through a small incision is less likely to create astigmatism, and may lead to a quicker recovery.”

Posterior Fixated Lens Issues

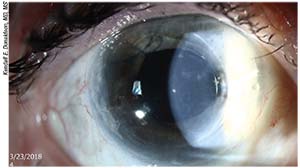

Although implanting an ACIOL comes

|

| A malpositioned anterior chamber IOL. These can be associated with endothelial failure with corneal edema; chronic intraocular inflammation, or uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema (UGH) syndrome; and cystoid macular edema. |

with several caveats, so do most techniques for fixating a posterior chamber lens. That makes the choice of which option to pursue a little more challenging.

Issues with lenses fixated in the posterior chamber include:

• Posterior chamber lenses can also have complications. “Posterior chamber fixated lenses are more likely to end up with lens tilt, and anticipating effective lens position will always be an issue,” notes Dr. Donaldson.

Dr. Fram agrees. “Obviously, the lenses can tilt, and any time you’re in the pars plana suturing you’re at a higher risk for retinal tear or detachment,” she says. “For all of my cases, I perform a careful retinal exam at one week, three weeks and two months. Patients are then followed every six months for maintenance. If the patient has a significant vitreous hemorrhage, or a retinal detachment warning sign such as flashes or floaters, I’ll send the patient to a retinal specialist to verify that there’s no retinal tear or detachment. You have to treat these cases and patients with the respect they deserve and monitor them carefully.”

• Fixating a posterior chamber lens is more technically difficult. “Suturing or gluing a posterior chamber IOL is much more technically difficult than placing an anterior chamber IOL, which usually only takes five to 10 minutes,” notes Dr. Donaldson. “There is definitely much more technique that has to be learned in order to place a posterior chamber lens in the absence of capsular support. I was recently at a symposium at which there was a whole two-hour section dedicated to the Yamane technique. One section was focused on complications; people were showing their nightmares, everything they did wrong. Other speakers shared the proper technique. If we can talk about that for two hours, obviously these techniques are not something you just run out and do without proper preparation and practice.

“For that reason, surgeon experience will be a factor here,” she continues. “The less-experienced the surgeon, the more likely it is that complications of one type or another will occur. So the answer as to which of these procedures is best for the patient may have a lot to do with how much experience the surgeon has had with the available surgical options.”

Dr. Donaldson acknowledges that there is also a small learning curve associated with placing an anterior chamber lens. “You have to do a peripheral iridotomy,” she says. “You have to know how to suture properly so you don’t induce a lot of corneal astigmatism, and you have to know how to make a good wound. There are a lot of small details that can make a big difference when putting in an anterior chamber lens, but they’re easily learned. I just think the learning curve is longer with some of the posterior chamber techniques, compared to properly placing an anterior chamber lens.”

|

• Posterior surgeries take longer. “This can be a problem if the patient has retinal issues or a history of uveitis,” notes Dr. Donaldson. “You’re more likely to have a vitreous hemorrhage or retinal complications with a longer, more complex case that involves suturing to the sclera, and you may experience iris chafing or uveitis with iris-sutured lenses. And of course, the likelihood of these problems will be greater in an older patient or a complex case when the patient has several pre-existing conditions.”

Do We Have a Winner?

Given that both anterior and posterior chamber lenses have drawbacks, should surgeons favor posterior chamber IOLs?

“In a retrospective study I participated in at Bascom Palmer in the early 2000s, we compared the outcomes in eyes with poor capsular support that received anterior chamber IOLs to those receiving sutured posterior chamber IOLs,” says Dr. Donaldson. “We found more postoperative astigmatism in the posterior chamber lenses, but overall, we found a similar incidence of complications in the two groups.”1

Dr. Fram agrees that the research published to date suggests that whether an anterior or posterior lens is chosen, the outcomes tend to be similar. “The Wagoner paper from 2003 compared properly placed anterior chamber IOLs to scleral- and iris suture-fixation techniques and found that all of the options were equivalent,” she says.2

“Of course, we don’t have long-term data for some of the newer techniques for scleral fixation, to compare them to anterior chamber fixation,” Dr. Weikert notes. “But to date, the literature shows them to be about the same under comparable circumstances.”

Dr. Donaldson adds that despite all of its potential problems, the anterior chamber lens option is less problematic than it was in the old days, thanks to improvements in lens design. “Thirty or 40 years ago we had closed-loop anterior chamber lenses,” she

|

| An anterior chamber lens that has developed uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema (UGH) syndrome. |

points out. “Today we have open-loop anterior chamber lenses that cause less fibrosis and less inflammation in the angle. The older lenses had a higher incidence of UGH syndrome; it was so common with those older model anterior chamber lenses that we developed a name for it! We still see it, but it’s not as common as it used to be. Patients do much better with the modern anterior chamber lenses.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Fram says she prefers to use a fixated posterior lens. “I’ve never met an anterior chamber IOL that I liked over the long term,” she says. “That’s why I was determined to learn other secondary IOL-fixation techniques.”

Dr. Donaldson notes that the option a surgeon chooses is usually based on factors such as surgeon experience, patient age and any co-morbid conditions such as glaucoma or retinal problems. Dr. Weikert offers another perspective: “Ultimately,” he says, “you’re choosing between potential intraoperative complications and potential postoperative complications.”

Surgeons offer the following tips for managing a situation involving weak or nonexistent zonular support and deciding whether to implant an ACIOL or fixate a posterior chamber lens.

Before Going to Surgery

If you know that you’re dealing with limited capsular support:

• When choosing your approach, consider the patient’s age. Dr. Weikert says that if you know ahead of time that you’re likely to be managing limited capsular support, it’s important to keep in mind the patient’s endothelial cell count and the long-term effect an anterior chamber lens might have. “I’m less inclined to use an anterior chamber lens if the patient is younger,” he says. “If a 50-year-old patient comes in who’s had trauma, or is aphakic and needs a secondary lens, if the eye has no capsule support I’ll favor scleral fixation. If the patient is 75 and has a good cornea, I might decide to implant an anterior chamber lens.”

• Get additional measurements. “About 90 percent of the time we can anticipate which patients will be at higher risk for an issue with lack of capsular support,” notes Dr. Donaldson. “In that situation, preoperative planning is key. We should already have the depth of the anterior chamber. Ideally we’d also get specular microscopy to look at the endothelial cells.”

• Talk to the patient. Dr. Donaldson says it’s important to address the reality that this surgery could be complex when prepping the patient for surgery. She notes that many patients with preop zonular problems are older. “They might be 90 or 93 years old,” she says. “They may have unpredictable eyes, and you may see pseudoexfoliative material on the anterior lens capsule. If the patient has pseudoexfoliation syndrome and you know the capsular support is somewhat compromised, you can talk to the patient about it preoperatively. That makes for a much easier conversation after surgery if a complication occurs.

“For example, I’ll say, ‘Your eye appears to be weaker than the average eye.’ I explain what pseudoexfoliation syndrome is. I may also mention other factors, such as having a very narrow angle that doesn’t give us much space in which to work. I tell them, ‘We’re going to do everything we can to put the lens exactly where we want it to be, but if your eye isn’t strong enough to tolerate a lens where we’d like it to be, I’ll be prepared to put the lens in an alternative position. Fortunately, we have some options, and we’ll do everything we can to get you the best possible outcome.’

“Once you have that conversation before surgery, the postoperative conversation is easier,” she says. “You can either say that everything went perfectly and the lens is right where you wanted it to be, or you can say, ‘As expected, we found that your eye was weaker than average, but we were still able to place the lens. We’ll just be using extra drops and so forth to handle it.’ It opens the window for further discussion.”

• Be prepared to deal with unexpected challenges. “Dr. Masket always says that you have to have plans A, B and C ready when you go into the OR,” Dr. Fram notes. “If you know a patient has pseudoexfoliation and the zonules could be affected, or if you know that a patient has had three vitrectomies and you find phacodonesis on the slit lamp exam, you have to be prepared with multiple options. It’s your obligation as a surgeon to be ready. The real difficulties arise when you’re not ready and a problem catches you off guard.

“Once you learn to manage the possible nonroutine scenarios, you can think on your feet,” she adds. “Until you do that, you’ll find it tough to think calmly and clearly in those situations.”

• If the case will be complex, schedule it when you have plenty of time. “If you know you’re doing a complicated case, schedule that case toward the end of the day,” says Dr. Donaldson. That way you’ll have extra time if you need it, so you don’t have to be as stressed. Do your easy cases first and save the more stressful cases for later.”

In the OR

Once you’re ready to operate:

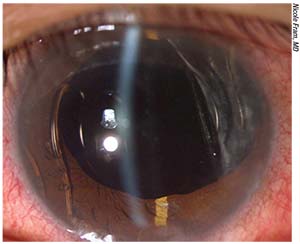

• Have the tools you might need for any of several options on hand. “Even when I’m planning to use one technique, I’ll make sure that I have other options available,” says Dr. Weikert. “If I’m planning for scleral fixation with, say, the Yamane technique, I’ll also make sure an anterior chamber lens is available, just in case. We recently had a case at our veterans hospital where we were going to use the Yamane technique, but we encountered some difficulties with our scleral passages; so, we

|

| The Yamane technique (above) is one of a number of recently developed ways to fixate a posterior chamber IOL. Fixating a lens posteriorly is presumed to be safer for the cornea than anterior chamber placement, but these techniques can be challenging and time- consuming to perform, and lenses in this location are also associated with complications. |

just changed gears and placed an anterior chamber lens. The patient was older—late 60s, early 70s—and had a good cornea. The bottom line is, no matter what you do, it’s always best to have multiple options.”

Dr. Donaldson agrees. “In a lot of these complicated cases in which we know that the eye is not normal, we might go in with two or three different IOLs,” she says. “We’ve already done the calculations for them. We also make sure we have the extra tools that can help us normalize a compromised capsule and allow us to put a posterior chamber lens in the bag, such as capsular tension rings and Ahmed segments. We wouldn’t have been able to do that years ago, and I’m thankful to our colleagues that have come up with these tools.”

• Be careful when choosing the size of an anterior segment lens. “The problem is, we were taught to measure the white-to-white length and then add 1 mm [when gauging the size of the space],” Dr. Fram notes. “That may not be accurate for a given patient. For one thing, the measurement will be different if you measure the white-to-white horizontally or vertically, so placement and location of the lens haptics matter. It could be that white-to-white plus 0.5 mm is more appropriate in some patients. Furthermore, many surgery centers and hospitals don’t stock all the different lens sizes, so surgeons often end up putting in a lens that’s too big or too small. A lens that’s too small ends up bouncing around and causing pigment dispersion and corneal endothelial failure. If it’s too big, you can get chronic iritis and CME, and eventually have corneal decompensation. It’s better to leave a patient aphakic and come back to place a secondary IOL than to place a malpositioned IOL.”

• When implanting an anterior chamber lens, make sure you seat it in the angle carefully. “If you see any iris distortion or ovalization of the pupil, recheck how the lens footplates are seated in the angle,” says Dr. Weikert. “If you can’t get the ovalization to go away by repositioning the lens, consider putting in a smaller lens, leaving the patient aphakic or shifting to scleral fixation.

“The dimensions of the anterior chamber are usually a little shorter vertically than horizontally,” he adds. “That means you can always rotate the lens inside the anterior chamber if you think it might sit better. If your incision is temporal and the lens appears loose after insertion, it may actually sit better in a vertical position.”

• Don’t be afraid to leave the eye aphakic. “If things didn’t go as planned, and you don’t feel confident that you’re going to end up with a

good result after placing a lens at the time of primary surgery, just leave the patient aphakic and come back later,” says Dr. Weikert. “If it’s been a long, difficult surgery, the cornea is barely hanging on and/or the patient is getting restless, you might create other issues if you try to implant an IOL.

“For example,” he continues, “in our practice we’ve seen complications such as UGH syndrome or cystoid macular edema resulting from single-piece IOLs being placed in the ciliary sulcus because the surgeon didn’t feel comfortable leaving the patient aphakic after a surgical complication. If the appropriate IOL model isn’t available, it’s far better to leave the patient aphakic and come back on a different day to implant an IOL under optimal conditions.”

Dr. Fram points out that in some stressful situations a surgeon might be tempted to try performing a procedure that he or she has only done a few times before, such as suturing a posterior chamber IOL to the iris or sclera. “That might not be the best choice,” she says. “If you’re caught off guard and you don’t know whether the eye is a good candidate for an anterior chamber lens, there’s nothing wrong with leaving the patient aphakic and cleaning everything up and coming back another day. If I’m doing a surgery and it’s an unstable situation and it’s already been two-and-a-half hours in the OR, I’m not

|

| Placement of an ACIOL led to corneal decompensation requiring DSEK surgery for visual rehabilitation for this monocular patient with a history of macular degeneration and retinal detachment repair. |

going to start a scleral suture fixation at that point. It’s often better to clean up the eye with a proper triamcinolone-assisted vitrectomy, let the eye calm down and come back at a later date. Although it may seem sacrilegious to leave the patient aphakic, in many situations, that’s the best thing to do. Admittedly, it does take courage.”

Dr. Fram notes that she herself rarely ends up leaving her patients aphakic because her mentors at Wills Eye Hospital and UCSF, and her practice partner for many years, Samuel Masket, MD, trained her to perform the complex anterior segment surgeries. “I’ve been fortunate to have been trained to perform these surgeries by giants,” she says.

ACIOLs: Still Worth Using?

“I do believe there’s still a place for an ACIOL, especially if that’s your best skill set,” Dr. Fram says. “If you get the measurements right, the chamber is deep, you’re well-trained to make a scleral tunnel with a frown incision to generate minimal astigmatic changes, and you know how to properly position the anterior chamber IOL, of course that should be your procedure. But those patients need to be monitored closely, and the lens should be exchanged if problems arise. Of course, this is also the case for scleral-fixated IOLs, because suture or haptic erosion can lead to endophthalmitis if not detected promptly. This is why we see patients every six months irrespective of the stability of the IOL and the refractive outcome.”

Dr. Fram says that although she prefers posterior segment placement, she does occasionally implant an anterior segment lens. “You have to consider the age of the patient, the patient’s coagulation status and how high-risk the surgery may become,” she says. “I probably put in one or two ACIOLs each year, when I believe the patient can‘t afford to stop [systemic] anticoagulants, or the eye can’t support an intrascleral or suture-fixation technique. However, in that situation it’s important to evaluate the anterior chamber depth and corneal health prior to placement, and to have appropriate lenses available based on a true white-to-white or sulcus measurement.

“Whether you end up using an ACIOL that’s been carefully planned or you perform a scleral-fixated posterior chamber IOL, that’s your choice as the surgeon,” she adds. “Until a prospective study comes out showing the true superiority of one technique over another, we’re going to have to say that the options are equivalent. Just do the surgery well, and make sure you watch for corneal edema, glaucoma, UGH syndrome and CME. And if a complication happens, deal with it early and consider an IOL exchange.”

Dr. Donaldson says she believes there is definitely still a place for anterior chamber lenses when capsular support is weak or missing. “Through the years our options have proliferated, so clearly there’s no perfect option that’s appropriate in every case,” she says. ”I think all of our residents and fellows need to be trained to place an anterior chamber lens. Putting in an anterior chamber lens is quick and easy, and may be the best choice in a sick eye or for an older patient who can’t undergo a more complicated surgery. And despite the concern about long-term complications, I have some patients who’ve had anterior chamber lenses for many years and have done very well. The anterior chamber lens has kind of gotten a bad rap.”

Dr. Fram says ultimately you should use the technique you feel most comfortable performing. “It doesn’t matter what secondary IOL technique you’re using as long as the IOL is properly chosen, fixated and monitored,” she says. “Just be sure to do your procedure well and reproducibly, and check the patient afterwards to make sure that your interventions are successful and safe for the patient.” REVIEW

Dr. Fram has previously consulted for Alcon. Drs. Donaldson and Weikert have no financial ties to any company mentioned.

1. Donaldson KE, Gorscak JJ, Budenz DL, et al. Anterior chamber and sutured posterior chamber intraocular lenses in eyes with poor capsular support. J Cataract Refract Surg 2005;31:5:903-9.

2. Wagoner MD, Cox TA, Ariyasu RG, Jacobs DS, Karp CL; American Academy of Ophthalmology. Intraocular lens implantation in the absence of capsular support: A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2003;110:4:840-59.