Although trabeculectomy is a powerful tool for a glaucoma surgeon, it comes with risks, some of which—although rare—are quite serious. Today, as the glaucoma surgery landscape evolves, the risk/benefit ratio associated with trabeculectomy keeps changing. If the risks associated with this surgery get smaller, but a failure is still potentially catastrophic, how do you respond? As more alternatives to trabeculectomy appear and slowly evolve, how does that change the equation?

Many surgeons still believe that trabeculectomy is irreplaceable, but to justify that position, it’s important to do everything possible to reduce the risks associated with this surgery. Unfortunately, a successful trabeculectomy isn’t just a question of surgeon skill. Marlene R. Moster, MD, a professor of ophthalmology at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University and an attending surgeon at Wills Eye Hospital Glaucoma Service in Philadelphia, notes that being an excellent surgeon experienced at performing trabeculectomies isn’t enough to ensure a great outcome. “Even if all goes smoothly in the OR,” she says, “unpredictable complications may occur postoperatively.”

Here, surgeons with extensive experience performing trabeculectomies offer advice on ways to reduce the different risks associated with the surgery, and share their thoughts about trabeculectomy’s place in the surgical armamentarium.

Preoperative Issues

|

|

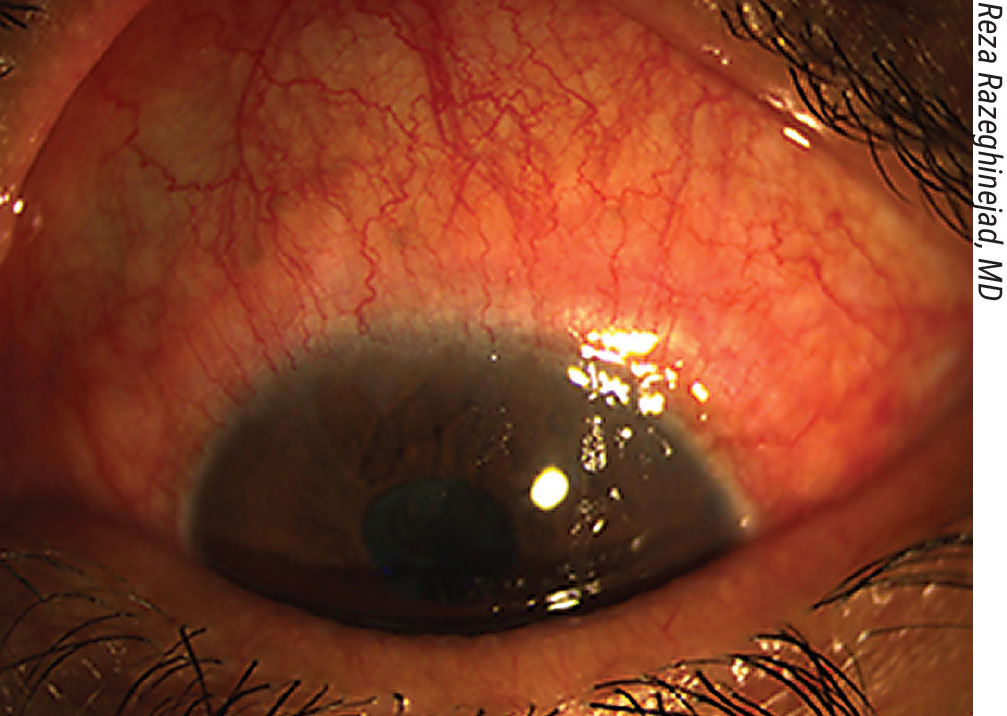

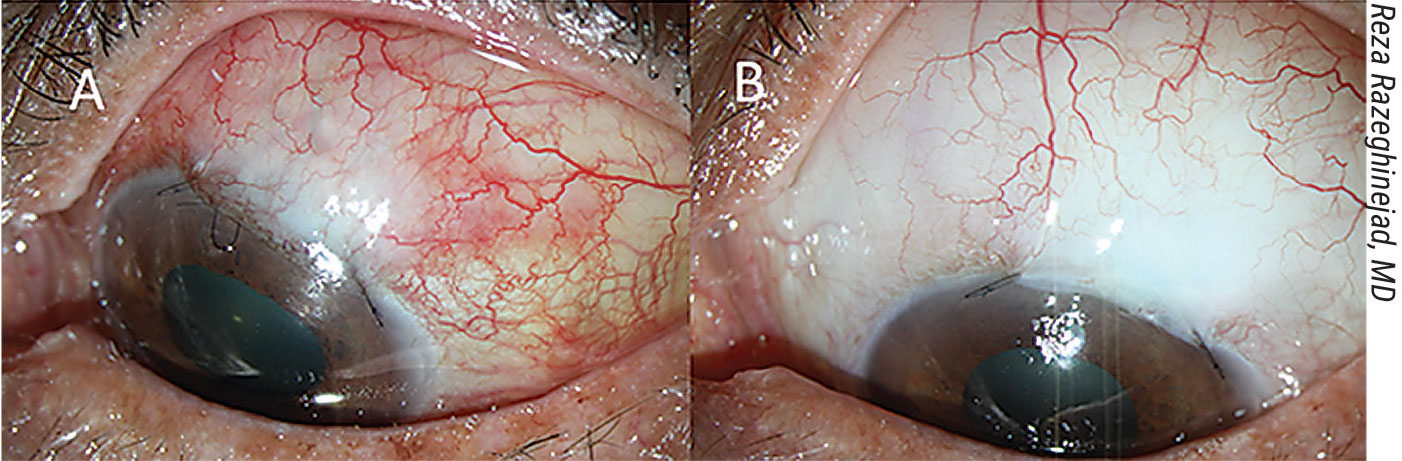

Inflammation on the ocular surface preop must be addressed; it can affect the outcome. Above: follicular allergic conjunctivitis secondary to the use of topical glaucoma medications. |

To help minimize the chance of unwanted complications, several issues should be addressed before the surgery:

• Manage any ocular surface inflammation. “Preop, we need to treat any inflammation we find, because inflammation on the ocular surface can affect the outcome,” says Reza Razeghinejad, MD, an associate professor of ophthalmology at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, and director of the glaucoma fellowship program at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia. “For example, a patient may have follicular conjunctivitis or allergic contact dermatitis because of topical medication use. (See figure to the right, above.) We need to stop the topical medication in these patients at least one week before surgery. I also start oral medication, because when you have a lot of inflammation you may have a lot of bleeding during the surgery, which can cause subconjunctival hemorrhages. That will eventually cause the procedure to fail.”

“Inflamed red eyes may be prone to scarring and early failure, and one of the reasons to do a trabeculectomy is to eliminate the need for topical medications, which in some cases can negatively affect both the cornea and vision,” says Dr. Moster. “When the patient needs to come off medication before surgery, I substitute oral acetazolamide and non-preserved artificial tears for a week, giving the eye a drop holiday. In addition to the preop topical steroids, I’ve tried using over-the-counter Lumify to whiten up the eye prior to surgery.

“It’s not always easy to take the patient off of medications,” she adds. “However, it’s my clinical impression that when the pressure is very high and the eye is very red, the medications aren’t working anyway.”

• Make sure blood pressure is controlled. “If the patient has high blood pressure, we need to make sure the blood pressure is controlled,” says Dr. Razeghinejad. “Uncontrolled blood pressure is a risk factor for suprachoroidal hemorrhage or effusion.”

• Make sure intraocular pressure isn’t too high. “We also need to lower a high IOP before surgery—at the very least in the preop area before bringing the patient back to the operating room,” Dr. Razeghinejad notes. “We can do this using an intravenous medication such as mannitol or acetazolamide. If we start the surgery with a very high IOP, as soon as we decompress the eye there’s a chance we may get suprachoroidal hemorrhage. If we can’t offer intravenous medications, we can create the side port first and lower the eye pressure gradually by accessing the side port before starting the surgery.”

Dr. Moster agrees. “If it’s not possible to lower the pressure before surgery, do a paracentesis in the OR at the start of the surgery,” she suggests. “Bring the IOP down to about 20 mmHg—not too low or too high. That will give the eye time to equilibrate.”

• Address the issue of blood-thinning medications. “Stopping blood thinners before surgery isn’t mandatory, but some surgeons do prefer to stop them,” notes Dr. Razeghinejad. “In that case, we need to coordinate with the primary care physician or cardiologist to make sure they’re OK with stopping the medication. In the meantime, when we stop it, we can put the patient on heparin, which has a short half-life. We can use that for a few days before taking the patient to the OR.

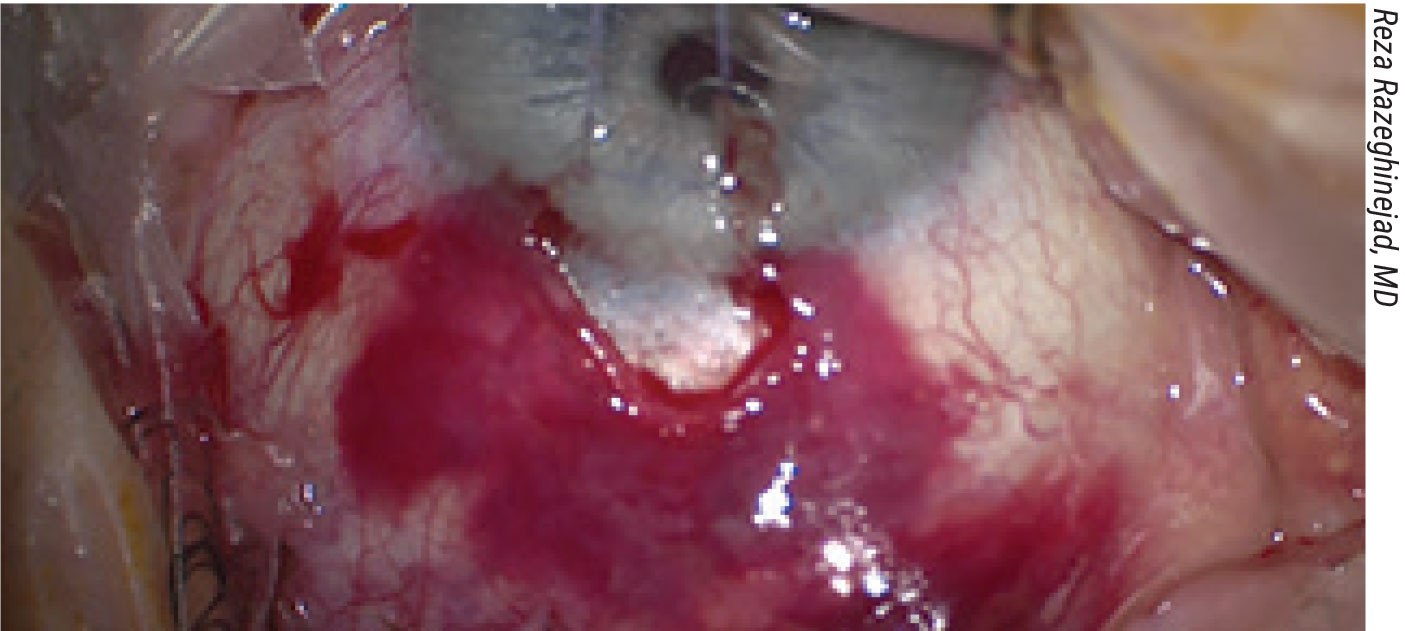

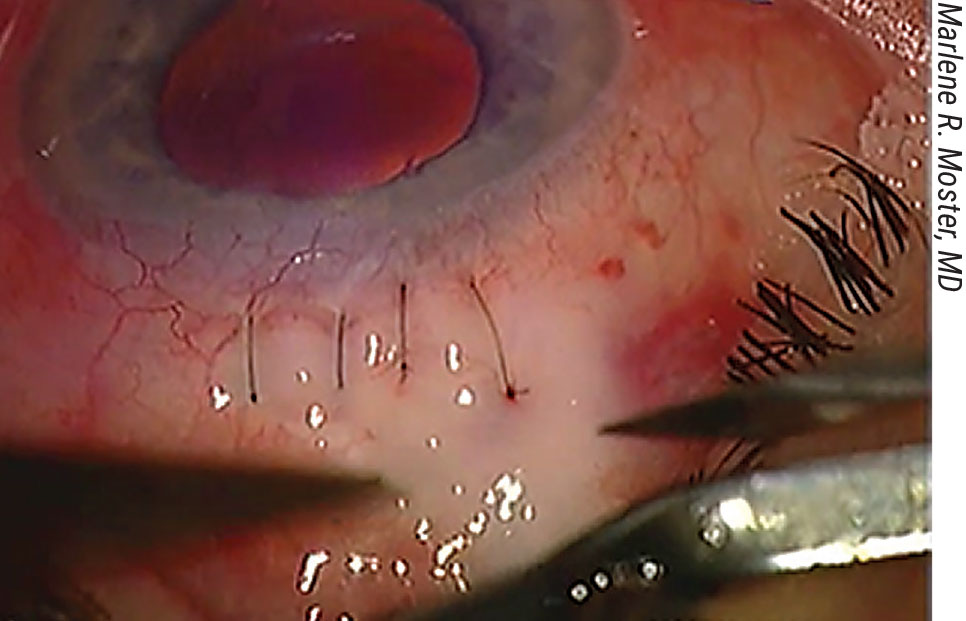

“The concern, of course, is getting bleeding in the subconjunctival space,” he continues. “This can eventually cause fibrosis and scar formation and failure of the procedure. (See image, p. 52) Or, we may get bleeding in the anterior chamber when we’re doing a peripheral iridectomy.

“These days, most glaucoma surgeons aren’t stopping the blood-thinning medications,” he concludes. “If you stop the medication and the patient develops a CVA or emboli, you’ll create another problem.”

Dr. Moster agrees. “I don’t typically stop blood thinners before the surgery due to the added risk of thromboembolic events,” she says. “We use topical, subconjunctival and intracameral lidocaine for anesthesia during a trabeculectomy, and avoid retrobulbar or peribulbar blocks entirely. This decreases the risk of an orbital bleed.”

• Set realistic patient expectations. “Before the surgery I usually have a long discussion with the patient about possible complications and postoperative IOP fluctuations,” says Dr. Razeghinejad. “When discussing possible complications, I talk about three major things: bleeding; infection; and effusion. In terms of the outcome, I explain that the pressure could be too low or too high after the surgery, and the patient may need to tolerate some adjustments during the first few weeks after surgery. I also explain that if this procedure fails, the patient may need to go back to the OR to do a revision or a shunt procedure. I prepare them for multiple possibilities, because we don’t know the nature of the healing process for each patient. It’s totally individualized.”

Intraoperative Concerns

|

|

A subconjuctival hemorrhage occuring during trabeculectomy. This type of unexpected complication can eventually lead to bleb failure. |

Dr. Moster notes that most complications occur postoperatively, not intraoperatively. Nevertheless, there are issues that can arise during the surgery. “Intraoperatively, the four things to look out for are suprachoroidal hemorrhage, malignant glaucoma, excessive unanticipated bleeding in the anterior segment, and a flat chamber caused by excessive aqueous flow,” she explains. “Fortunately, these are pretty rare.”

Dr. Moster offers this advice for managing these issues, should they arise:

• Malignant glaucoma. “Sometimes this occurs during a trabeculectomy,” she notes. “The eye becomes incredibly hard due to aqueous being trapped behind the lens. That’s a very uncomfortable situation for both the patient and the surgeon.

“Ultimately, to manage malignant glaucoma, medications are tried first,” says Dr. Moster. “If those are not successful, either a YAG laser rupture of the vitreous face or a surgical vitrectomy is needed to create a unicameral eye; an iridectomy is always required to eliminate the possibility of pupillary block. Once the diagnosis is made, the pupil can be dilated and mannitol administered intravenously, which may break the attack. If that isn’t successful, a vitrectomy will need to be performed to disrupt the anterior vitreous face. Often, the aqueous has readjusted by the next day, the chamber has increased in depth and the intraocular pressure has stabilized. Pupillary dilation is maintained throughout the postoperative course.

“More often than not, in a pseudophake, you can disrupt the vitreous face directly through the iridectomy,” she notes. “Noemi Lois, MD, showed that in a pseudophakic eye, a vitrector can be used to go through the iris, the zonules and the anterior vitreous face to make a unicameral eye, breaking the attack, in almost every case. A phakic eye is a lot more worrisome. If the chamber is shallow and the pressure is high, then the patient will need a retina consult for a full vitrectomy in order to reverse the aqueous misdirection.”

• Bleeding. “Another common problem that can occur is increased bleeding due to blood thinners,” notes Dr. Moster. “As noted, I don’t typically stop blood thinners before the surgery due to the added risk of thromboembolic events. Usually, we can control surface bleeding without incident. However, on occasion there can be bleeding during an iridectomy, and it’s impossible to predict.”

• A flat chamber. “During the trabeculectomy, try to prevent the chamber from flattening,” advises Dr. Moster. “It’s best to avoid hypotony so that choroidals don’t develop during the procedure. That’s especially true for high myopes, where a tube, ExPress Shunt or GATT procedure might be a better choice. I prefer a GATT for some myopes, to avoid the need for mitomycin-C and the risk of hypotony maculopathy.

“In rare cases the chamber may flatten because there’s too much outflow under the scleral flap, and more sutures are needed to control the situation,” she adds. “In general, it’s never a good idea to leave the chamber flat. We always try to reinflate the eye quickly using balanced salt solution or viscoelastic to deepen the eye, and then close the scleral flap up tight to re-establish the anatomy. The releasable or laserable sutures can later be removed for postoperative pressure control.”1

• Suprachoroidal hemorrhage. “This is another feared complication of trabeculectomy,” Dr. Moster notes. “While doing the trabeculectomy, one of the posterior blood vessels within the choroid can rupture. This is akin to an air-bag explosion, and the chamber becomes shallow. When the IOP is elevated, you must close that eye very quickly to avoid an expulsive hemorrhage.”

Dr. Razeghinejad notes several surgical issues that can reduce or increase the likelihood of complications during the operation:

• Placing the traction suture. “The location of the traction suture can be an issue,” he says. “Previously, everybody was putting the traction suture under the superior rectus, but these days most surgeons prefer to use a clear-cornea traction suture. This seems to be safer because there are a lot of blood vessels around the superior rectus muscle; when you pass the needle through, you can get a subconjunctival heme, leading to more fibrosis and surgery failure.”

• Making the peritomy. “Before creating the peritomy, we inject mitomycin-C, in all patients,” Dr. Razeghinejad says. “We usually inject 0.1 ml of a 0.4-mg/ml concentration, mixed with 2% lidocaine. We inject this under the conjunctiva about 5 mm posterior to the limbus before opening the conjunctiva. Patients who are young and highly myopic are prone to hypotony after trabeculectomy, so for those patients we may use a concentration of 0.2 mg/ml instead of 0.4.

“To open the conjunctiva you have two different possible approaches: a fornix-based peritomy or a limbus-based peritomy,” he continues. “Overall, fornix-based peritomies are preferred because we have better exposure, and the likelihood of the bleb extending to the posterior is higher.”

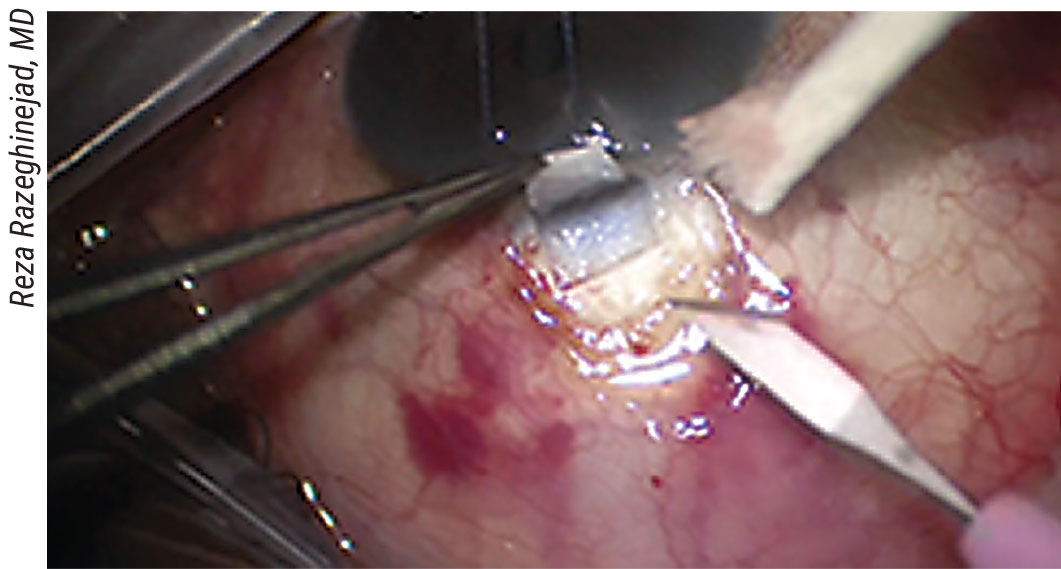

• Creating the scleral flap. “The surgeon can create many different flap shapes,” notes Dr. Razeghinejad. “Overall, there’s no major difference between them. There’s only one major concern when creating the flap—to avoid cutting beyond the area in which there’s original conjunctival attachment to the limbus. (See picture, p. 55) If we do that, we may get postop leakage and a shallow anterior chamber. Also, in patients who have low scleral rigidity—for example, those with congenital glaucoma or high myopia—we should avoid creating a large scleral flap, because it will cause a significant amount of astigmatism.”

• Making the ostomy. “When making the ostomy we should avoid going too far posteriorly because it can cause bleeding,” explains Dr. Razeghinejad. “It can also cause a cyclodialysis cleft, or even vitreous loss.”

• Creating a peripheral iridotomy. “Whether or not a PI is done depends on the surgeon and the patient’s condition,” Dr. Razeghinejad notes. “For example, if a patient has had previous cataract surgery, doing a PI isn’t mandatory, but if the patient is phakic, he definitely needs the PI.

“When making a PI it may be better to avoid injecting lidocaine intracamerally,” he continues. “Injecting lidocaine can cause pupillary dilation and make the PI harder to do. Also, in patients who have a short eye or plateau iris syndrome, we need to be aware that the ciliary processes are a bit anterior. We should avoid cutting them in the process of making the PI.”

• Closing the flap. “We may use interrupted permanent sutures or releasable sutures to close the scleral flap,” notes Dr. Razeghinejad. “If we’re just using non-releasable sutures for closing the flap, it’s better to have a long-arm suture, because it’s easier to bury it. Also, if we’re doing suture lysis after the surgery, finding the suture is easier.”

• Closing the conjunctiva. “Some surgeons use 10-0 nylon to close the conjunctiva; some use 8-0 vicryl sutures,” says Dr. Razeghinejad. “If you use 8-0 vicryl, it’s better to use the vascular needle instead of the cutting or spatulated needles because the latter can cause conjunctival buttonholing. However, if you’re using 10-0 nylon sutures, you can use any needle. The hole created in the conjunctiva is very small, and you’re not concerned about tearing the conjunctiva and having leakage.”

Dr. Moster adds that it’s helpful to take steps to minimize postoperative scarring. “To help avoid this, I use a small amount of intracameral steroid, such as non-preserved triamcinolone, and when possible, a steroid pellet like Dextenza placed in the inferior punctum,” she explains. “This helps to address the issue of poor compliance with topical steroids postoperatively.”

Postop Complications

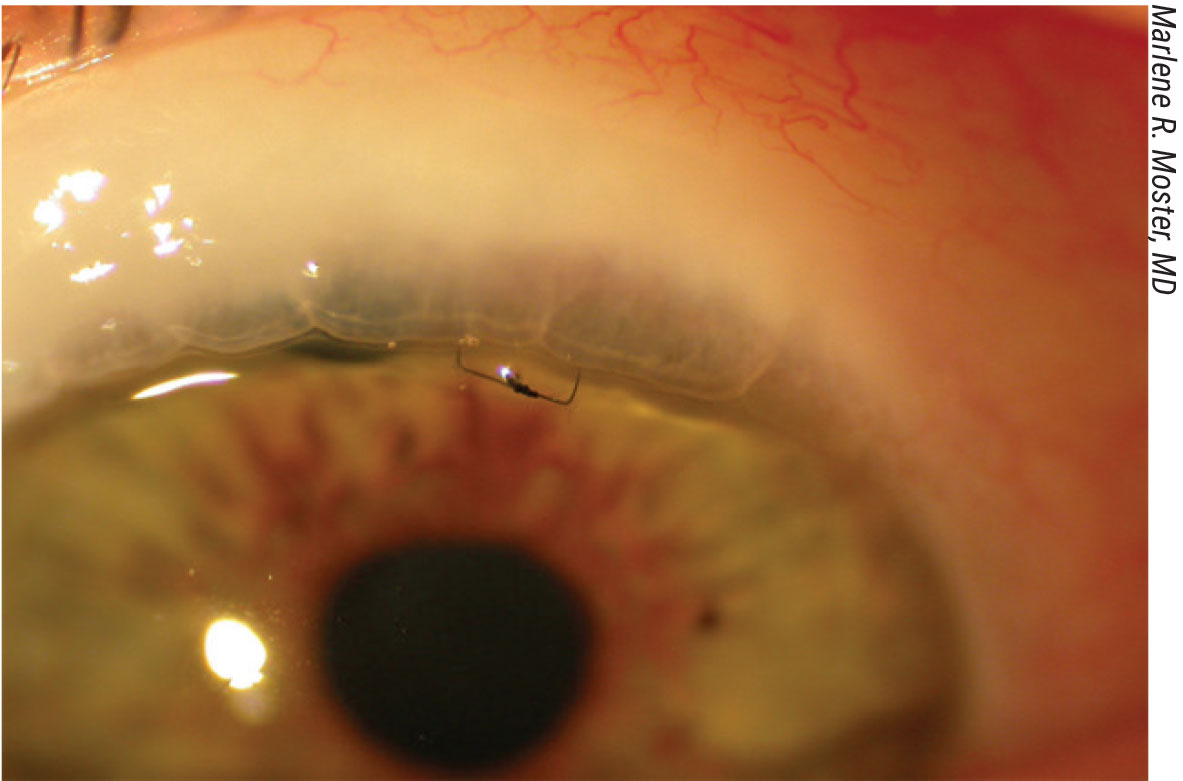

“There are a number of issues we need to address during the postop period, including astigmatism from sutures, cataract formation and the remote possibility of endophthalmitis,” says Dr. Moster. “The releasable suture usually comes out between one and three weeks; the vicryl running suture closing the fornix-based flap will dissolve by itself. Patients are usually on antibiotics for only one week. If the chamber is shallow, I dilate the eye; if not, I don’t.

“The goal,” she adds, “is to stop all glaucoma medications postop.”

One major issue to manage is the use of postoperative steroids. Dr. Razeghinejad advises being generous about their use. “After the surgery we see a lot of conjunctival inflammation,” he explains. “Using a good amount of steroid is really important, because if we don’t, the inflammation may promote the healing process and eventually lead to fibrosis and failure of the procedure.”

“I start the steroids four times a day for two weeks, tapering down by one drop each week,” notes Dr. Moster. “That makes a total of eight weeks of steroids.”

|

|

The radial incisions for the scleral flap shouldn’t go beyond the line of original conjunctival attachment to the limbus surgeons say. |

“The amount of steroids we use depends on the amount of inflammation and congestion we see in the bleb area,” says Dr. Razeghinejad. “We may need to put some patients on a steroid every two hours for the first few days after the surgery. Depending on the congestion, we may need to keep the patient on the steroid for three or even four months—although in some cases, we may be able to stop the steroid after a month or two. If the patient doesn’t respond to the steroid drops and we see a lot of congestion, we can inject mitomycin-C or 5-FU under the conjunctiva around the bleb area to delay the healing process and keep the bleb functioning.”

Other issues that may arise in some patients include:

• Scarring that interferes with outflow through the bleb. “This can happen either early or late within the postop period,” notes Dr. Moster. “It can be managed by needling the bleb with the addition of MM-C or 5-FU.”

“Bleb needling can be done in the office,” notes Dr. Razeghinejad. “Sometimes it works; sometimes not. If it doesn’t work, we need to go under the flap with the needle and lift the edge of the flap. As soon as we see some flow under the conjunctiva, we can take the needle out. It may be helpful to inject some 5-FU or MM-C under the conjunctiva.

“Eventually, if all of these fail,” he adds, “we need to consider doing a bleb revision, or a tube shunt surgery.”

Dr. Moster says the ability to use needling to potentially resolve this problem is one reason she prefers trabs as first-line rather than tubes. “If the trab fails, needling will bring it back to life in about 64 percent of cases,” she says.2 “Unfortunately, tubes are not amenable to this.”

• A plugged ostomy. “If the pressure is up after trabeculectomy and we don’t have any bleb, first we need to do a gonioscopy,” says Dr. Razeghinejad. “Sometimes iris tissue plugs the ostomy you’ve created. In this situation we can use pilocarpine eye drops a couple of times in the office to take the iris out of the ostomy and release the iris tissue. If that doesn’t work, we may do a YAG laser using a goniolens, applying the laser at the interface of the iris tissue and the border of the ostomy. If the IOP remains elevated after the iris is released, we can do suture lysis—cut one of the sutures over the flap, or remove one of the releasable sutures to enhance flow under the conjunctiva. If all of these fail to get the bleb back to normal function, we need to consider doing bleb needling.”

• A bleb leak from the incisional site. “If this occurs, you can try a bandage contact lens, use cautery to close the leak, or take the patient back to the OR and put in an extra stitch,” says Dr. Moster. “We always check the wound with a fluorescein strip prior to leaving the OR to make sure the wound is watertight.”

• Hypotony. “Of course, hypotony caused by over-filtration is always a potential issue,” says Dr. Moster. “When dealing with postop hypotony, dilate the pupil; consider using viscoelastic to deepen the chamber, or consider putting trans-conjunctival sutures through the bleb to increase the resistance within the bleb.3

“A good way to decrease postop complications in general is to use either laserable or releasable sutures to help keep the IOP where you want it,” she adds. “I currently use releasable sutures and remove them as needed at the slit lamp. They help control the postop flow during the first three weeks. If the pressure is starting at a higher level, I tie the releasable suture down tight; I don’t want the pressure to be very low on the first day.”

• Tenon’s cyst formation. “This is something you may occasionally encounter,” says Dr. Moster. “It can be addressed by waiting until the cyst softens.”

• Blebs migrating onto the corneal surface. “This occasionally happens,” notes Dr. Moster. “Currently, however, we’re primarily doing fornix-based flaps, so that both cysts and migrating blebs are becoming a rare phenomenon.”

Patient Management Postop

Aside from managing any postop complications that occur, it’s important to continue to keep the patient’s expectations realistic. “I explain to each patient that early on their vision will be blurry due to the sutures and fluctuating intraocular pressure,” says Dr. Moster. “There are generally one or two sutures that need to be removed by three weeks, but everything else dissolves. Beyond that, I usually tell them it will take about eight weeks to be off all drops and be over and done.”

Dr. Razeghinejad says he prepares the patient for the possibility of a problem. “After the surgery, the two major things we’re concerned about are suprachoroidal hemorrhage and endophthalmitis,” he notes. “Once the surgery is done I usually tell the patient: ‘If you have any more pain or redness than what you have now, or any worsening of your vision, you need to call us.’ Those symptoms could mean a number of things, so we’ll need to examine the patient.”

|

|

A releasable suture (above) usually comes out between one and three weeks postop. |

Dr. Razeghinejad says he generally sees the patient on day one, and if everything continues to be fine, the next visit is a week later. “Then we’ll see the patient every two to three weeks for the first two months after the surgery,” he says. “If everything is still OK, we’ll see the patient again a month after that. This covers the whole three postoperative months. However, we feel lucky when we have a patient like that; we see most patients more frequently. Sometimes the pressure is high or low postop; we may find a shallow anterior chamber or leakage; or we may find choroidal effusion. It’s unusual to have a patient who doesn’t need any laser suture lysis or an MM-C or 5-FU injection or other interventions in-office. Most patients need something.”

Dr. Moster says she sees patients the day after surgery and at week one. “After that, I see the patient sometime within the following two weeks, to make sure the pressure is at the goal and the releasable suture is out,” she explains. “I check them again in one month; then I individualize the timing. Generally, once the wound is stable and the pressure’s on target, I send the patient back to the referring doctor.

“Everything has to be individualized to the patient’s circumstances,” she adds. “The reality is, every patient has a different history, different comorbidities and different ocular issues.”

Are Trabs On the Way Out?

It’s no secret that use of trabeculectomy has been declining in recent years, with a concurrent increase in the number of tubes being performed. This downward trend in the use of trabeculectomy has led to considerable debate regarding whether trabeculectomy is still a viable choice for patients, and whether the decline in its use may have unintended side effects.

“Fewer and fewer ophthalmologists know how to do a successful trabeculectomy,” says Dr. Moster. “It’s becoming a lost art. There’s a trend toward doing more tubes, but nothing works as well as a good trabeculectomy. I’ve seen trabeculectomies work well beyond 15 years, with the patients needing zero medications. This has been the case in both Caucasians and African-American patients. So, if someone needs a low IOP, I prefer a trabeculectomy. I’ll do everything I can to avoid complications—which is the issue surgeons worry about.”

|

|

A) A congested bleb, before increasing the steroid dose. B) The same eye four weeks after high-dose topical steroid therapy and removal of the releasable suture. |

“I think there’s still room for trabeculectomy,” says Dr. Razeghinejad. “We use it in many situations where other procedures aren’t working. For example, it’s a good solution for a young patient with pigmentary glaucoma who’s concerned about having diplopia following tube shunt surgery. The XEN isn’t an ideal choice because these patients have pigment in the anterior chamber that can clog the stent. So trabeculectomy is our only option. If the patient is young and phakic, a GATT or goniotomy procedure may not work, so trabeculectomy seems to be the best option.

“Also, a MIGS procedure may not work for many phakic patients with high pressure that need surgery,” he continues. “Most MIGS procedures are based on bypassing the trabecular meshwork, and if you have any problem downstream, the pressure will stay high after the MIGS procedure. Furthermore, most MIGS procedures have to be combined with cataract surgery, and many glaucoma patients don’t need cataract surgery.”

“Our glaucoma patient population includes an ever-increasing shift towards older age, with proportionately more patients in their 80s, 90s and beyond,” notes Kuldev Singh, MD, MPH, a professor of ophthalmology and chief of the Glaucoma Division at the Stanford University School of Medicine in California. “As patients live longer, we’ll see more of them who will have advanced disease and a need for very low IOPs during their lifetimes, sometimes only attainable with skillfully performed trabeculectomy. Despite this, current circumstances—including the training required to learn trabeculectomy, the substantial postoperative care and insufficient reimbursement associated with this procedure, and the presence of easier, but not as effective options—are moving many surgeons away from performing trabeculectomy in patients who need this procedure.

“This trend could lead to a downward spiral of surgeon skill,” he points out. “Surgeons experienced with performing trabeculectomy may dwindle in number, leading to more problematic surgical outcomes in the hands of less-experienced surgeons, and, ultimately, fewer surgeons wanting to perform the procedure. Trabeculectomy is in danger of becoming a lost art, which I believe will create a public health problem.

“Despite this trend, a number of studies have confirmed the unique power of a trabeculectomy,” he adds. “Studies have shown that trabeculectomy can significantly reduce the likelihood of disease progression,4,5 improve visual function6 and produce lower IOPs than other options, when needed.7 So trabeculectomy is a procedure that very much needs to remain a part of our armamentarium.

“Not every fellowship-trained glaucoma specialist will continue to perform trabeculectomy, and, of course, nobody can force them to do so,” he concludes. “But trabeculectomy, when performed skillfully and followed by appropriate postoperative care, is sometimes the best approach to prevent blindness in those with advanced and/or high-risk glaucomatous disease.”

Are Tube Shunts the Answer?

|

|

Full-thickness trans-conjunctival sutures can be used to treat hypotony. |

Andrew Iwach, MD, the executive director of the Glaucoma Center of San Francisco and an associate clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of California, says that until a few years ago, he did plenty of filtering surgeries. “The problem with bleb-based surgeries, regardless of your technique, is that they’re a setup for potential long-term trouble,” he notes. “Blebitis can lead to endophthalmitis, which, although uncommon, can result in a patient who has good vision at the outset losing significant vision or even an eye—a catastrophic outcome.

“About seven years ago I carefully reviewed what we were doing,” he says. “At that time, we were modifying our surgical approaches with tube shunts, such as the designs we were using and our technique as to tube and plate placement, to lower risk, and the risk profile for tube shunt surgery started going down. For example, we were doing some research combining tube surgery with subsequent judicious use of laser cyclophotocoagulation. We found that just a little bit of laser as an adjunct could produce excellent results. Only about 25 percent of our tube shunt patients needed the subsequent laser treatment, but the combination showed excellent stability and a low complication rate. (We presented our data on this at the 2019 meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology.) With this protocol, the postop follow-up is much simpler and typically safer. This improvement in our tube shunt protocol caused me to begin rethinking the role of trabeculectomy.

“Our practice was very successful with trabeculectomy, and a pioneer in the use of antimetabolites, but I was troubled by the long-term risk profile,” he continues. “The risk was incrementally small—but when it hit, it could be devastating. So, after being an innovator and enthusiast for trabeculectomy for most of my career, I walked away from creating blebs. Now I haven’t done a bleb-based surgery for at least five years.

“I’m not saying that trabeculectomies shouldn’t be done at all,” he notes. “Some of my colleagues get very good results, and they should continue to do them. But more globally, my concern is that we’re leaving people with filtering blebs that are at ongoing risk for trauma and endophthalmitis. I think the continuing risks of trabeculectomy, and our improved understanding and techniques for using tube shunts, have helped change people’s perspective and may account for the gradual shift away from trabeculectomy to the increased use of tube shunts.

“I think those taking care of glaucoma patients need to keep the bigger picture in mind,” he concludes. “We need to consider the impact on quality of life and the risk of catastrophic events when performing surgeries that create blebs. There are many ways to make a trabeculectomy safer, such as laser suture lysis, positioning and so on. But at the end of the day, we’re still creating an opening—a potential passageway for bacteria from the surface to the inside of the eye—in tissue that’s been subjected to glaucoma drugs for years, and often on top of mitomycin exposure at the time of surgery. I don’t see an easy fix to the long-term bleb-related risk. In many cases, we get away with it. But in a few cases, it’s catastrophic.”

However, many surgeons have reservations. Dr. Moster says she doesn’t find tubes to be an ideal first choice. “Very few tubes are totally successful on their own—meaning no glaucoma medication, no complications or decreased vision,” she says. “If you look at the five-year treatment outcome of the Ahmed versus Baerveldt comparison study,8 the number of complete successes at five years was nine (8 percent) in the Ahmed tube group and 14 (14 percent) in the Baerveldt tube group (p=0.27). That’s not optimal.

“For me,” she continues, “the biggest issue with tubes is that once they fail, the superior conjunctiva is limited, often requiring a second tube to be placed inferiorly. That’s why I prefer a superior trabeculectomy. If the trabeculectomy doesn’t work, I can needle it with mitomycin-C; and if that still doesn’t work, the patient can always get a tube. Nothing is lost.

“I do regularly implant tubes in uveitic patients, some pseudophakes, those patients who work in sub-optimal environments, and older people who live far away,” she notes. “Every patient has to be treated as a unique case.”

Dr. Moster adds that in recent years she’s tried to substitute MIGS procedures in as many patients as possible to decrease complications. “Unfortunately, MIGS doesn’t always produce low enough IOPs,” she says. “Patients with real glaucoma often end up back on medications.”

“In the long run, some ophthalmologists may choose to do more tube shunts than trabeculectomies because the postop care is easier,” notes Dr. Razeghinejad. “However, I’m not sure it’s safer for the patient. If you do a shunt and it fails in two years, and the patient is young and phakic, what else can you do? You need to put another one in in a different quadrant. If you do a trabeculectomy and it fails in two years, you can put in a tube and you have a few more years for it to work. But if you do the tube first, it may be impossible to go back and do a trabeculectomy later.”

Dr. Razeghinejad adds that the range of corneal complications with tube shunts is much greater than with trabeculectomy. “When we do a tube shunt, we need to consider the long-term complications,” he explains. “If you do a tube shunt on a 45-year-old patient and see the patient for four years, you may not see a problem in the cornea. But if you follow that patient for 15 years, the cornea may eventually fail and the patient may need a corneal transplant. On the other hand, if you do a trabeculectomy and it works for 10 years, the likelihood of needing a corneal transplant is very low.”

Dr. Razeghinejad notes that the reason for this longer-term risk with tube shunts isn’t completely clear. “We understand why the cornea is at risk if the tube is touching the cornea,” he says. “But in those patients where the tube isn’t touching the cornea, we still see endothelial cell loss. It may be just because we’re leaving a foreign body inside the anterior chamber. However, some people hypothesize that the convection inside the anterior chamber changes when you have a tube in there. It’s believed that the aqueous produced by the ciliary body goes through the pupil and then flows downward to the inferior angle and then up to the superior angle. When we place a tube in the superior angle, the aqueous that’s produced by the ciliary processes passes through the pupil and then goes directly into the tube. This change in the aqueous convection may have a negative impact on the corneal endothelial cells. This is just a hypothesis, but it seems reasonable.”

Dr. Iwach is a consultant to Ivantis and New World Medical and is on the speaker’s bureau for Bausch + Lomb and New World Medical. Dr. Singh is a consultant for Alcon, Allergan, Santen, Sight Sciences, Glaukos and Ivantis. Drs. Moster and Razeghinejad report no relevant financial disclosures.

1. Duman F, Faria B, Rutnin N, et al. Comparison of three different releasable suture techniques in trabeculectomy. Eur J Ophthalmol 2016;10;26:4:307-14.

2. Shetty RK, Wartluft L, Moster MR. Slit-lamp needle revision of failed filtering blebs using high-dose mitomycin C. J Glaucoma 2005;14:1:52-6.

3. Richman J, Moster MR, Myeni T, Trubnik V. A prospective study of consecutive patients undergoing full-thickness conjunctival/scleral hypotony sutures for clinical ocular hypotony. J Glaucoma 2014;23:5:326-8.

4. Mataki N, Murata H, Sawada A, et al. Visual field progression rate in normal tension glaucoma before and after trabeculectomy: A subfield-based analysis. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol 2014;3:263-266.

5. Iverson SM, Schulyz SK, Shi W, et al. Effectiveness of single-digit IOP targets on decreasing global and localized visual field progression after filtration surgery in eyes with progressive normal tension glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2016;25: 408-414.

6. Caprioli J, de Leon JM, Azarbod P, et al. Trabeculectomy can improve long-term visual function in glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2016;123:117-128.

7. Meyer AM, Rosenberg NC, Rodgers CD, et al. Attaining intraocular pressure of 10 mm Hg or less: comparison of tube and trabeculectomy surgery in pseudophakic primary glaucoma eyes. Asia Pacific J Ophthalmol 2019;8:489-500.

8. Budenz DL, Barton K, Gedde SJ, Feuer WJ, Schiffman J, Costa VP, Godfrey DG, Buys YM; Ahmed Baerveldt Comparison Study Group. Five-year treatment outcomes in the Ahmed Baerveldt comparison study. Ophthalmology 2015;122:2:308-16.