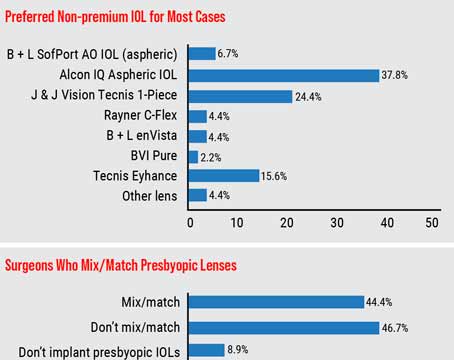

|

|

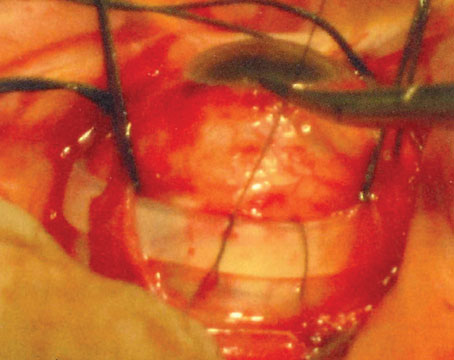

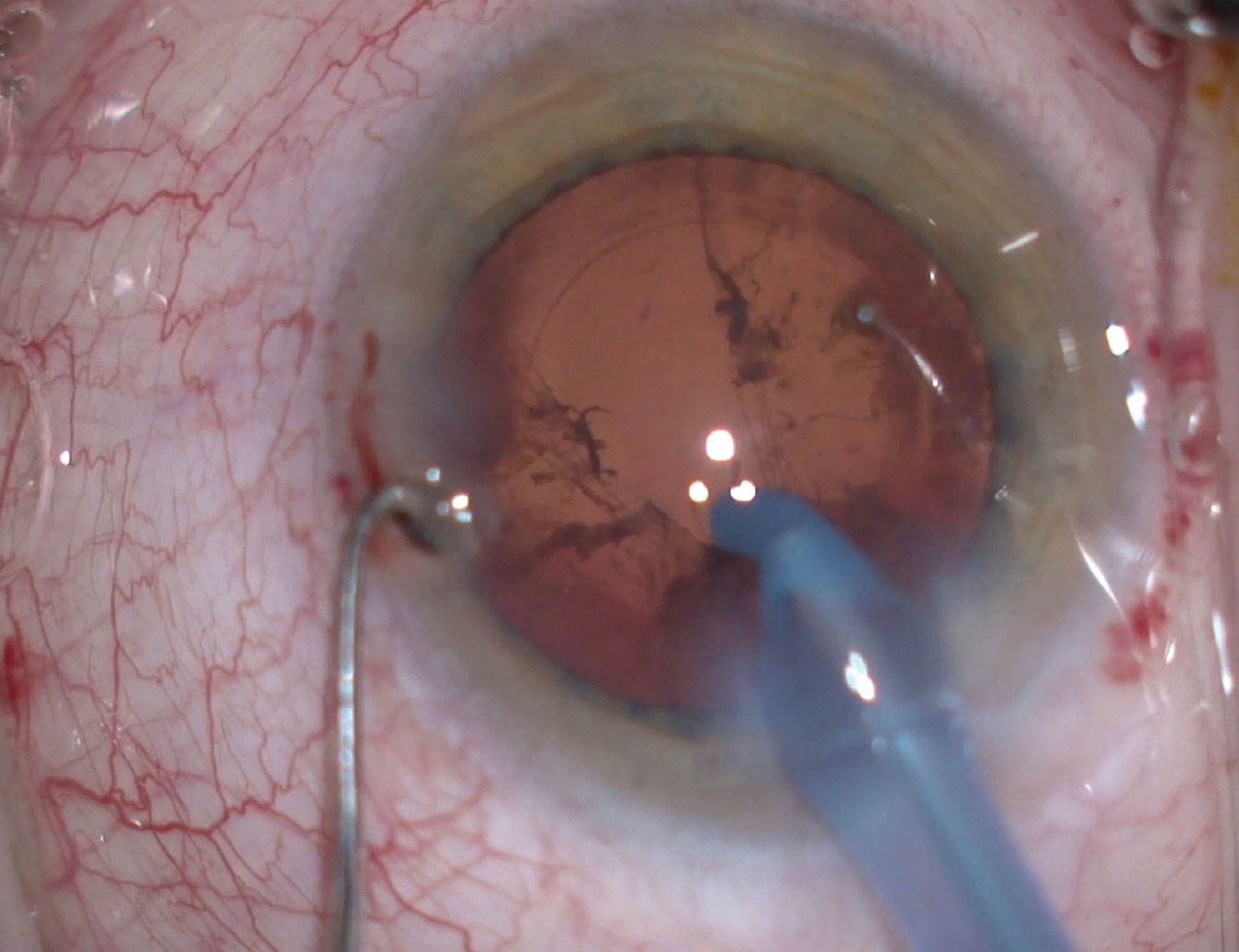

Figure 1. An early choroidal hemorrhage like this one would require an immediate termination of cataract surgery and referral to a retinal specialist. Image courtesy of Richard Hoffman, MD. |

As a surgeon, you’re likely all too familiar with the many things that can go wrong when implanting IOLs, ranging from lens dislocations to posterior capsular tears. This month, experts offer insights on how to respond confidently to four major challenges that can catch surgeons off guard, potentially leading to significant complications and setbacks. Read on to gain insights on intraoperative zonular weakness or loss, a sudden flat chamber and firm eye, a broken capsule with a lost nucleus and wound burn.

When Zonules Fail

You’re working on an eye and you realize that many clock hours are gone or weak. How do you respond?

“If the lens is stable and in good position, you may just want to leave it the way it is,” says Mark Kontos, MD, a senior partner at Empire Eye Physicians, with offices in eastern Washington and northern Idaho. “Watch it carefully until you’re assured that the stability will endure. If you’ve noticed this issue when there are still significant steps left to be taken in the surgery, then, yes, it will have a significant impact, especially if you still have most of the lens in the bag.”

If possible, Dr. Kontos tries to remove all the cortical material that isn’t in the area of zonular loss. “Sometimes, I’ll switch to a two-piece I/A, which is gentler on the eye and the bag,” he notes. “If I determine that I shouldn’t mess with the cortex, I’ll try to create some structure in the area, perhaps with a capsular tension ring or three-piece IOL. Then I remove the remaining cortex once those structures are in place, providing the support I need.”

In more serious cases, such as a loss of five clock hours of zonules or more, Dr. Kontos may turn to a Cionni ring. “You just have to be ready to adjust your technique, but you should always put the least amount of stress on the capsular bag that you can, to avoid losing the bag altogether.”

Proceed with Caution

If he detects mild zonular weakness during a procedure, Richard Hoffman, MD, continues with the case. “You can usually get through it by delicately performing your hydrodissection and rotating the lens carefully, using a two-handed rotation,” says Dr. Hoffman, clinical associate professor of ophthalmology at Oregon Health and Science University and a private practitioner at Drs. Fine, Hoffman, & Sims in Eugene, Oregon. “If you’re a divide-and-conquer surgeon, you can use a chopping method that puts less stress on the zonules.”

When dealing with a dense lens, Dr. Hoffman is inclined to place capsular hooks, especially when the zonular weakness is extensive.

“You can use either localized zonular capsule hooks in an area of frank zonular loss or, if you have generalized zonular weakness or loss, you can use four capsule hooks around the periphery of the capsule, providing equal support of the lens,” Dr. Hoffman says. He also uses the hooks prophylactically before surgery to avoid zonular tears, or dehiscence in patients who have known pseudoexfoliation, zonular weakness or, in some cases, very dense cataracts.

“Some surgeons might end up putting a capsular tension ring in at the same time as the capsule hooks to support the equator,” he says. “But I find the capsule hooks are, in general, all you need.

|

|

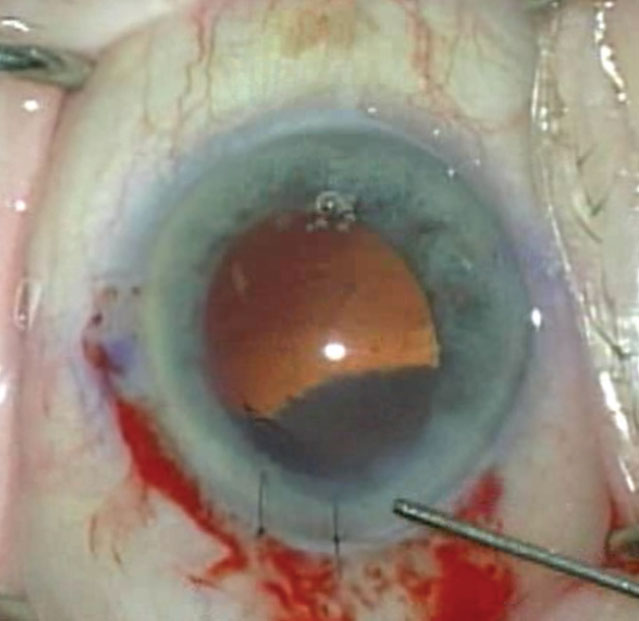

Figure 2. Weak zonules and poor dilation can be risk factors for posterior capsular tears. Using iris hooks and a capsular tension ring can decrease those risks. Image courtesy of Zaina Al-Mohtaseb, MD. |

“Once you have the lens out, you need to decide if you want to get by with just a capsular tension ring or add a scleral fixation device, such as an Ahmed segment or a Cionni ring segment,” he adds. It depends on how many clock hours of zonular weakness are involved and whether it’s progressive. Some of these pseudoexfoliation cases tend to progress and the patient can end up with a subluxed IOL seven or eight years after surgery. I put a capsular tension ring in all of these patients to respond to this possible situation in the future.”

If your patient has extensive zonular loss and still has a lot of the cataract in place, Nick Mamalis, MD, a professor of ophthalmology at the John A. Moran Eye Center, University of Utah, urges you to support the capsular bag while you’re removing what’s left of the cataract. When removing the cortex, he recommends you do so more tangentially, instead of toward the center of the capsule, to minimize stress on the zonules.

“Spread out the forceps on the zonules, so you won’t exacerbate the zonular tear,” he adds. Once he gets his bag adequately fixated in one of these cases, Dr. Mamalis prefers to use a one-piece hydrophobic acrylic IOL with haptics. “It’s easy to insert in the bag and holds up well if the bag is adequately supported,” he notes.

Zonular dehiscence in these patients is probably more common than most ophthalmologists realize, according to Robert M. Kershner, MD, MS, FACS, chairman of the Department of Ophthalmic Medical Technology at Palm Beach State College, Palm Beach Gardens, Florida. “More often than not, zonular dehiscence may not be obvious to the surgeon,” he says.

If you’re very conscientious and conservative about your surgery, staying within the center of the anterior chamber, Dr. Kershner says you might not notice or appreciate the effects of unsupportive zonules until you’re fairly far along in your case. “It may become obvious only after you’ve removed the cataract or when you’re about to implant the IOL,” he says. “At one of those points, you may notice that part of the capsule is more toward the center than another part and that, possibly, even vitreous is starting to come around. So it pays to check for good zonular support when you start the procedure.”

A Sudden Flat Chamber and Firm Eye

“The issue with a sudden flat chamber and firm eye is determining if you have a suprachoroidal hemorrhage or a choroidal effusion on your hands,” says Dr. Kontos. “In such a case, I’m considering risk factors, such as a small eye or uncontrolled hypertension. There are only a few ocular emergencies in cataract surgery, and this is one of them. Sometimes, though, it’s from balanced salt solution that’s gotten through the zonules, putting pressure on the vitreous.

“If you confirm a suprachoroidal hemorrhage after evaluating the retina, then you immediately have to get the eye closed. Any instruments in the eye have to come out. If you have the ability to get a little bit of viscoelastic in there and then close up the eye with a suture, then do it.”

Dr. Hoffman says the most common cause of a sudden flat chamber and firm eye in his practice is the misdirection of infused fluid from the phaco tip. “Be that as it may, however, you still need to treat this as a potential choroidal hemorrhage, which could evolve into an expulsive choroidal hemorrhage, even though that’s rare. So I will pull out of the eye and suture with one or two sutures to stabilize it.”

Like many of his colleagues in this situation, Dr. Hoffman pushes his microscope aside and turns to a retinal specialist’s indirect ophthalmoscope and 20-D lens, typically found in operating rooms, to study the retina for the dark brown color of a hemorrhage, the slightly different appearance of an effusion or an elevated retina. All of these signs signal a need to end surgery and refer the patient to a retinal specialist, he says.

“If, as usual, it’s infusion misdirection, you can usually wait it out because that condition can improve on its own,” Dr. Hoffman says. “You can go into your other OR to do another procedure or, if necessary, have the patient rolled to a waiting area for 30 to 60 minutes, while mannitol is administered. That eye will usually have softened up, allowing you to eventually finish the case, even if it has to be on another day in the unlikely event that it doesn’t resolve during that brief waiting period.”

In today’s era of small-incision surgery, Dr. Mamalis gratefully acknowledges that the risk of an expulsive choroidal hemorrhage has been reduced. “Nonetheless, you want to get your anterior segment under control and even put in a suture immediately, if necessary,” he says. If he sees evidence of a choroidal hemorrhage or effusion, he says he’ll obtain an immediate consultation from a retinal specialist, who may wait 10 to 14 days for the clot to liquify and dissolve before working on the eye. “Once the retinal specialist has finished with the patient, you can go in and do what you need to do, whether it’s removing some remaining material in the eye or putting in your intraocular lens in a more controlled setting,” says Dr. Mamalis.

Broken Capsule with Lost Nucleus

Either all or a large part of the nucleus may be lost in these cases, surgeons note.

“This is one of those events that makes your heart go up into your throat,” says Dr. Kontos. “You have to just stop the surgery and you have to fight the urge to go fishing for nuclear fragments. If you have a torn capsule and you’ve lost a piece of nucleus down in the vitreous, you have to accept that and realize this isn’t the end of the world. You’ll need to refer the patient to a retinal specialist. That’s sometimes just part of cataract surgery.”

Dr. Kontos removes what vitreous he can, hoping to avoid vitreous prolapse. “If there are any pieces of the nucleus that you can keep in the anterior chamber, use viscoelastic to elevate them and get them when you can before turning the case over to the specialist,” he says.

When a capsule breaks on him, Dr. Hoffman determines if the anterior capsulotomy is still intact. “It usually is intact,” he says. “I’ll clean everything up, make sure there’s no vitreous in the anterior chamber and try to get as much of the nucleus out as possible, with a combination of vitrectomy and phacoemulsification. If the whole lens or part of the lens has dropped, I clean up as much of the residual cortex as I can with my vitrectomy instrument, so that I’m not putting any traction on the vitreous. If the anterior segment is clean, I go ahead and put a three-piece lens in the sulcus and use optic capture to implant the optic through the intact capsulorhexis. You need to keep the vitreous from coming forward. Then you’ll need to have the retinal specialist come in and clean up the mess that you’ve created in the back of the eye.”

When one of his residents breaks a capsule, Dr. Mamalis is on alert. “I find that residents will often panic, and the first thing they want to do is yank that phaco tip out of the eye,” Dr. Mamalis says. “If they do that, the chamber shallows and the capsule will tear even more. You need to keep your foot on the pedal and go to position one. Then inject OVD through a stab incision, putting it over the capsule tear and inside your chamber.”

|

|

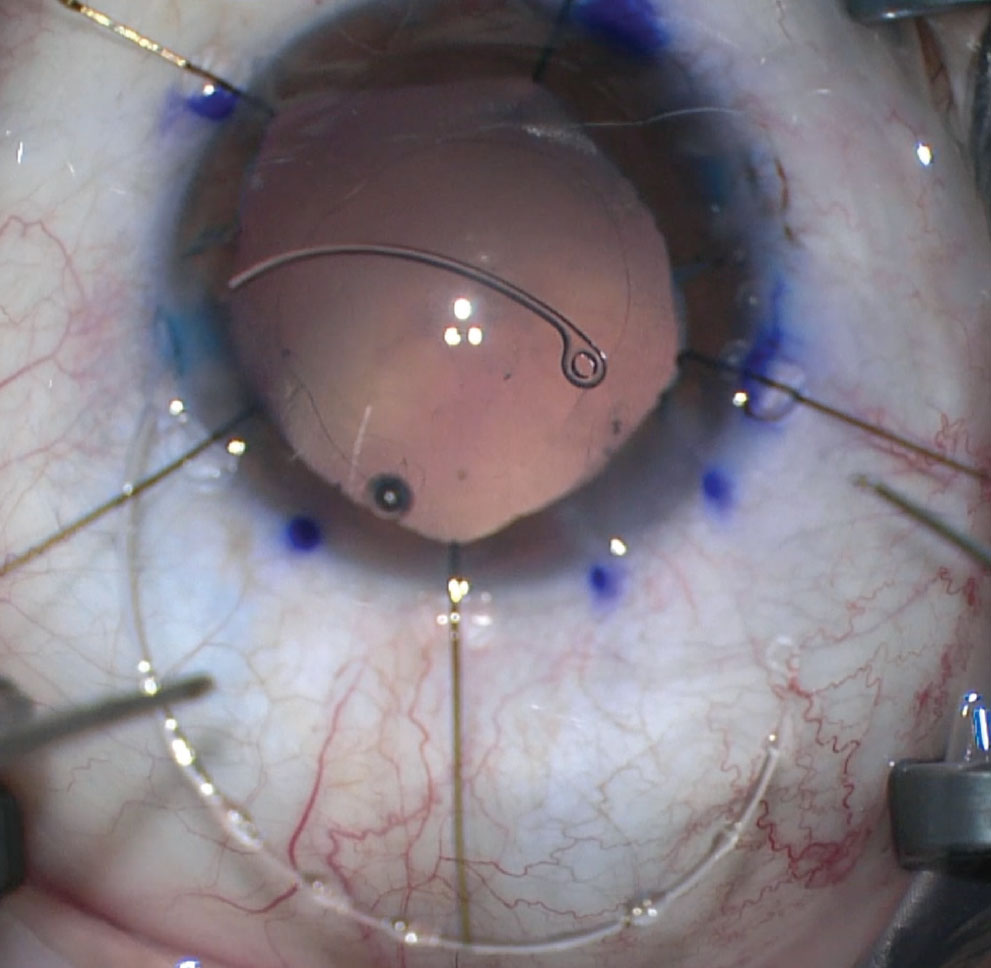

Figure 3. Even after a posterior capsular tear, you may still have the opportunity to remove cortical material. Image courtesy of Douglas K. Grayson, MD. |

Dr. Mamalis notes that you can still anteriorly remove fragments of nucleus without doing further damage. “You can even put a little lens glide underneath the fragments or you can put a wall of OVD underneath them. Then you can carefully remove what’s left of that nucleus without having it sink back toward the retina. But don’t be tempted to go in and get nucleus that’s sunk posteriorly into the vitreous. That’s a serious, costly error.”

“When they perform a capsulorhexis, I tell surgeons to read the capsule,” says Dr. Kershner. “If the capsule tears really easily and seems to be very thin, remember that the posterior capsule is going to be a third thinner than that.” In such a patient, he continues, the risks of a broken capsule are extremely high.

“The first thing to do is stop and recognize the adverse event as it occurs,” he says. “If you have an anterior tear, your job is to make sure it doesn’t extend posteriorly. And if it does extend posteriorly, make darn sure that you don’t allow vitreous to escape through it. Worse yet, you could have the lens exit through the posterior capsular tear.”

In very elderly patients, he notes, the risk of this type of complication is greatest because vitreous syneresis reduces or eliminates support behind the capsule. “Any tear is going to easily allow posterior vitreous contents in the vitreous cavity to enter the capsular bag and, possibly, the anterior chamber,” he says. “In almost all cases, the better part of valor is to admit the complication, do the best you can to clean things up and close the wound securely so that the vitroretinal surgeon can step in to help.”

Wound Burn

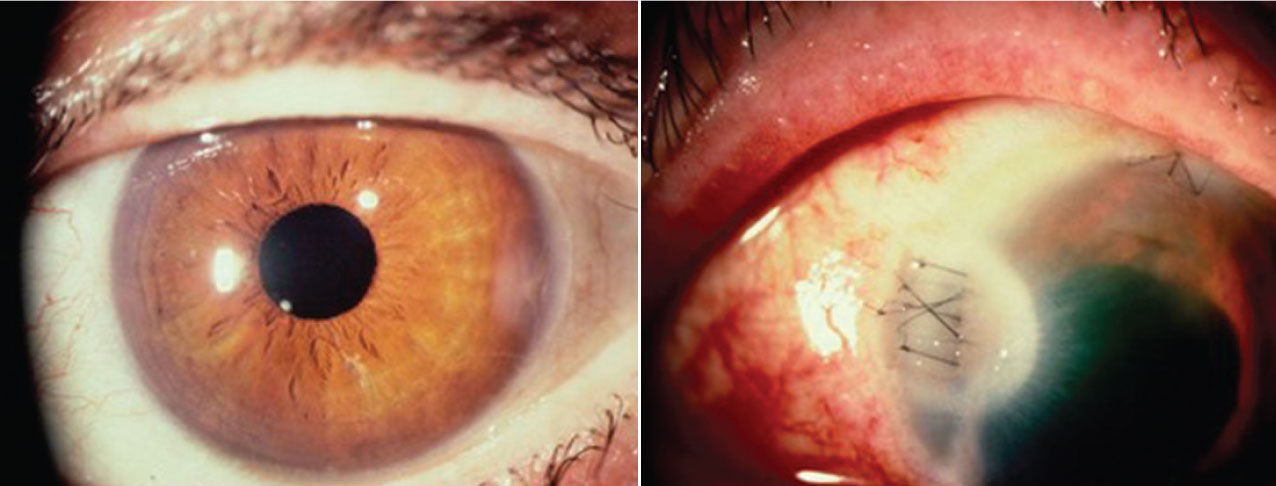

Although rare these days, a wound burn can still occur—suddenly and without warning. What are the best ways to avoid it and respond if it occurs?

“You just have to recognize it and stop phacoemulsification as quickly as possible,” Dr. Kontos says. “Usually, it’s because the phaco tip has become occluded and the fluid isn’t able to flow through the needle. The heat builds up very quickly. You can see evidence of this if you keep a close watch on the tip of your phaco handpiece. You get this thick, milky-white material forming at the tip. That’s your cue to stop your phaco and let the fluid continue to flow to provide irrigation. Usually, a wound burn occurs if you don’t recognize it and you keep the phaco going.”

Once a burn occurs, how you should respond depends on the degree of the burn, according to Dr. Kontos. “You may have to go to a different site on the cornea to create a new wound,” he says. “It depends on where you are in the case. Then the question becomes: How do you close the wound that was burned? You have to put in so many sutures and tie them so tightly that you will create a tremendous amount of astigmatism. What I was taught to do and have used successfully a couple of times is make a frown-shaped, relaxing incision posterior to the wound in the sclera. That lets tissue slide forward and allows you to suture the actual incision closed without creating as much astigmatism and needing to tie it quite so tightly. Then, you can usually use the new incision to complete the case, unless there’s a reason not to continue right away, such as a burned wound that’s leaking.”

Dr. Hoffman says a wound burn is always possible if you’re working on a very dense lens. “To avoid this, use energy that’s modulated, so that your phaco isn’t turned on continuously,” he says. “For a patient with a very dense cataract, you might want to make your entry wound a little bit larger. This can result in a lot of fluid coming out around the eye and the phaco tip, which helps to keep the tip from getting too hot.”

Another risk to avoid is working in a really tight wound, he adds. “In that situation, you’re pulling up on the phaco needle and cutting off the infusion fluid,” he says. “You could end up kinking the sleeve. Besides making sure you don’t kink off the infusion and make the wound too small, use refrigerated balance salt solution and avoid oar-locking. If you take these precautions, your risk of causing a wound burn will be significantly reduced. If the patient has a rock-hard cataract, ask your assistant to focus on the phaco needle when it enters the eye and to let you know immediately if he or she notices anything unusual, such as the wound area getting white.”

|

|

Figures 4 and 5. A wound burn, occurring in a flash, can go from minor (left) to severe (right) in a matter of seconds. Image courtesy of Kevin M. Miller, MD. |

Once a burn has occurred, Dr. Hoffman says you can suture the wound closed if you’ve caught it early enough. “Sometimes you have to put in several cross sutures, but rarely do you have to glue it,” he says. “Seal the wound as best you can and then move to make a new wound in a different location, probably a scleral incision 90 degrees away.”

Although he’s never had a wound burn occur in his hands, Dr. Mamalis says he has seen more than he’d care to when operating with his residents, some of whom charge into procedures too eagerly at times, risking this complication. To prevent this from occurring under his watch, he tells them to always enter the eye with just the irrigation turned on initially. “Then I tell them to aspirate some of that super-cohesive OVD,” he says. “The idea is that you want to establish circulation of BSS around that phaco tip before beginning phacoemulsification.”

Like Dr. Hoffman, Dr. Mamalis views a small, tight wound as a needless risk factor for a wound burn. “Avoid thinking you have to make your incision smaller than the last surgeon,” he says. “Surgeons have a tendency to do that. If you make an incision that’s too small and you have a phaco tip that doesn’t properly fit the size of that incision, you can actually block off the circulation. Remember that you need to keep that needle cool. If you block off that flow, the heat that comes from the ultrasound can go up to 50 degrees centigrade in literally a second or two. That wound will turn white. You want to recognize it and respond before any other damage occurs. You need to immediately stop phacoemulsification but keep irrigating like heck on the surface before you pull out. Once that wound burn happens, it happens. There’s nothing you can do but stop it from getting worse.”

Do No Harm

Dr. Kershner, who’s consulted with defendants and claimants on many eye surgery lawsuits through the years, says that any number of circumstances can arise that will challenge today’s surgeon.

“Above all, though, one of the biggest problems I see is a failure to refer or get help,” he notes. “Nobody will ever fault a surgeon for an unexpected adverse event, for a complication from surgery, unless that surgeon made it worse or denied it. So if you think about leaving it alone, that you’re not going to do anything about it, this is what will get you into trouble. The term for that is ‘falling below the standard of care.’ What we do isn’t always perfect. But we must always do whatever we can to serve the best interests of the patient. Remember the Hippocratic oath: Primum non nocere.”

Dr. Kontos is a consultant for Zeiss, Sun, Allergan and Johnson & Johnson Vision. Dr. Hoffman is a consultant for Microsurgical Technologies. Drs. Mamalis and Kershner report no relationships with companies that make products mentioned in this article.